Anatomy of the Female and Male Reproductive Organ

Subtopic:

Internal and External Female Reproductive Organs

Female Reproductive System

Key roles of the female reproductive system include:

Egg (ovum) production: The system is responsible for creating female gametes.

Sperm reception: It is structured to receive sperm cells.

Creating a conducive environment for fertilization and fetal development: Providing the necessary conditions for the union of gametes and subsequent growth of the fetus.

Childbirth (parturition): Facilitating the process of delivering a baby.

Breast milk production (lactation): Producing milk to nourish the newborn in early life.

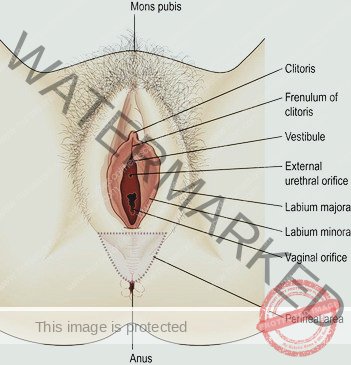

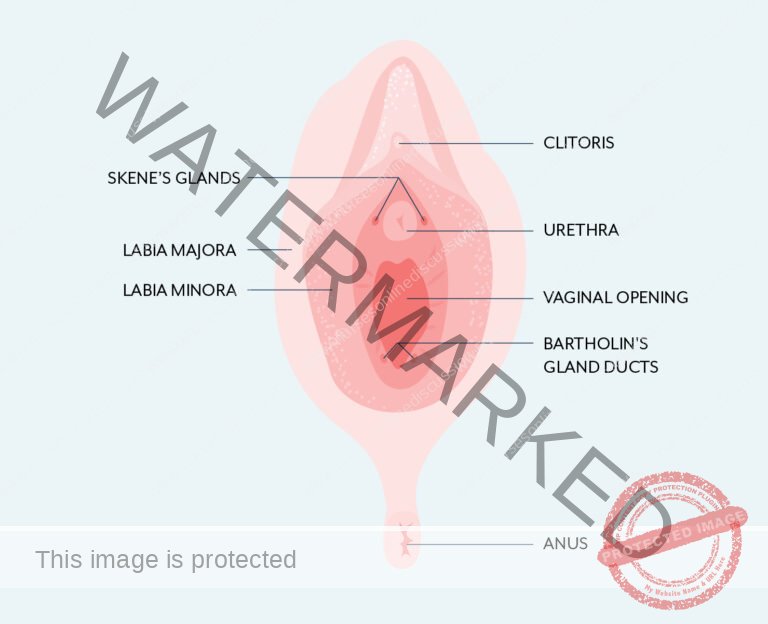

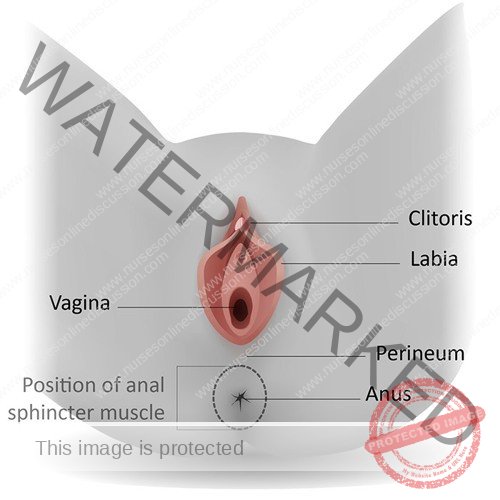

External Genitalia (Vulva)

The external female reproductive organs, collectively known as the vulva, comprise the following components:

Labia Majora: Outer folds of skin.

Labia Minora: Inner folds of skin, located within the labia majora.

Clitoris: A highly sensitive erectile organ.

Vaginal Orifice: The opening to the vagina.

Vestibule: The area enclosed by the labia minora, containing the openings of the urethra and vagina.

Hymen: A membrane that may partially cover the vaginal opening.

Vestibular Glands (Bartholin’s glands): Glands located on each side of the vaginal opening that secrete lubricating fluid.

Labia majora

Definition: These are the prominent, larger, outer skin folds that delineate the external boundary of the vulva.

Structure: Composed of skin, underlying fibrous connective tissue, and fatty tissue. They are abundant in sebaceous glands and eccrine sweat glands.

Location & Connection: In the front, they converge anterior to the pubic symphysis (the cartilaginous joint of the pubic bones). Posteriorly, they merge with the skin of the perineum (area between the genitals and anus).

Hair Development: During puberty, hair growth occurs on the mons pubis (the fatty tissue over the pubic bone) and the outward-facing surfaces of the labia majora.

Labia minora

Definition: These are the smaller, inner folds of skin situated between the labia majora.

Glandular Tissue: They also possess numerous sebaceous glands and eccrine sweat glands.

Vestibule Formation: The space or cleft located between the labia minora is known as the vestibule.

Vestibular Openings: The vestibule serves as the entry point for the vagina, the urethra (urinary opening), and the ducts of the greater vestibular glands (Bartholin’s glands).

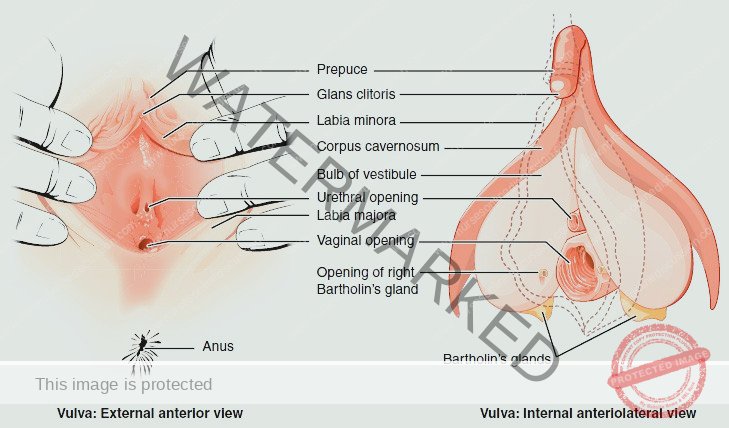

Clitoris

Analogy to Penis: The clitoris is the female equivalent to the penis in males, sharing a similar embryonic origin and function in sexual sensation. It is primarily composed of sensory nerve endings and erectile tissue, making it highly sensitive to stimulation.

Structure: This small, cylindrical organ is made up of two corpora cavernosa (erectile bodies), alongside a dense network of nerves and blood vessels. This structure enables engorgement with blood during sexual arousal, leading to erection.

Location: Situated at the anterior meeting point of the labia minora.

Prepuce of the Clitoris: A protective fold of skin, analogous to the penile foreskin, formed by the union of the labia minora. It covers the body of the clitoris.

Glans Clitoris: The visible, exposed tip of the clitoris, which is particularly rich in nerve endings and responsible for heightened sensation.

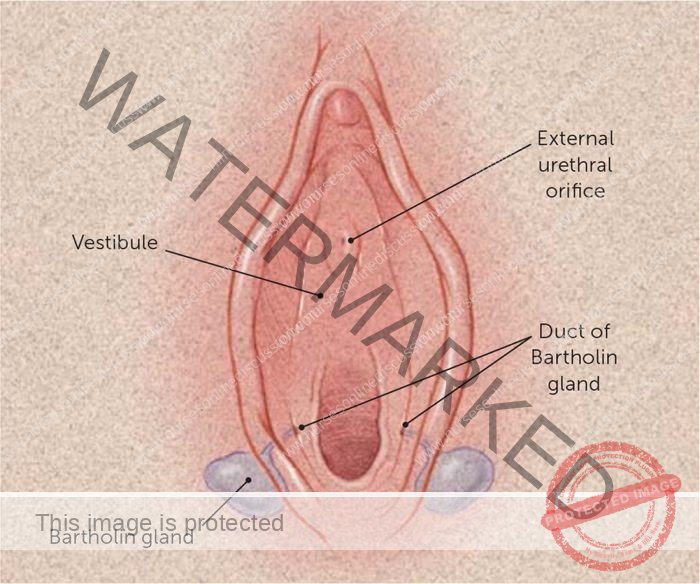

Vestibule

Definition: The vestibule is the anatomical area located and enclosed by the labia minora.

Contents: This region houses several key structures, including:

Hymen: (if intact) a membrane that may be present at the vaginal opening.

Vaginal Orifice: The entrance to the vagina.

External Urethral Orifice: The opening of the urethra to the outside of the body, located in front of the vaginal opening and behind the clitoris.

Glandular Openings: Ducts from various glands also open into the vestibule.

Paraurethral Glands (Skene’s glands) openings: Situated on either side of the external urethral orifice. These glands, located within the urethral wall, secrete mucus.

Greater Vestibular Glands (Bartholin’s glands) openings: Located on each side of the vaginal orifice itself. Their ducts open into a groove between the hymen and labia minora. These glands release a small amount of mucus during sexual excitement and intercourse, contributing to lubrication along with cervical mucus.

Hymen

Description: The hymen is a delicate membrane composed of mucous tissue. It is positioned to partially cover the vaginal opening.

Normal Structure: Typically, the hymen is not completely closed, featuring an opening to allow menstrual flow to exit the body.

Changes over time: The hymen can be stretched or torn during sexual intercourse (coitus) and is significantly altered during childbirth.

Vestibular glands(Bartholin’s glands)

The vestibular glands (Bartholin’s glands) are situated one on each side near the vaginal opening.

They are about the size of a small pea and have ducts, opening into the vestibule immediately lateral to the attachment of the hymen.

They secrete mucus that keeps the vulva moist.

Perineum

The perineum is a roughly triangular area extending from the base of the labia minora to the anal canal

It consists of connective tissue, muscle and fat. It gives attachment to the muscles of the pelvic floor

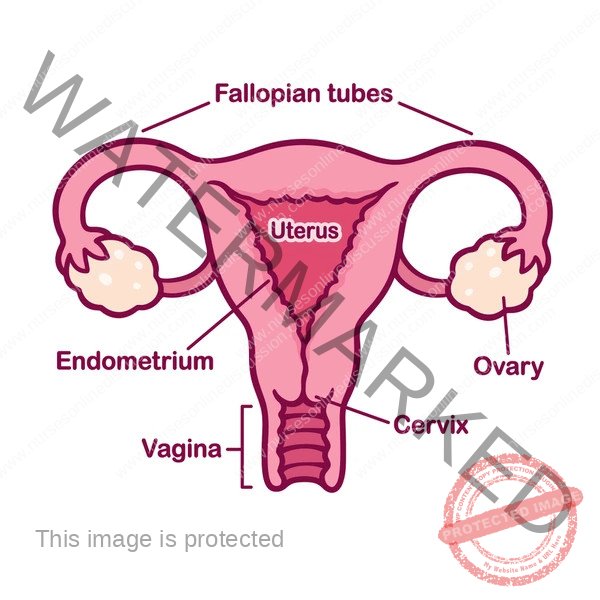

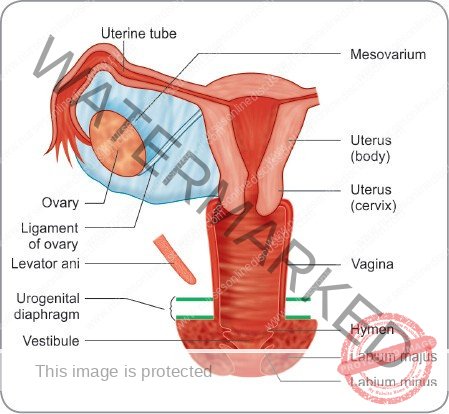

Internal Genitalia

The internal female reproductive organs are positioned within the pelvic cavity. These include:

Vagina

Uterus

Two Uterine Tubes (also known as Fallopian tubes)

Two Ovaries

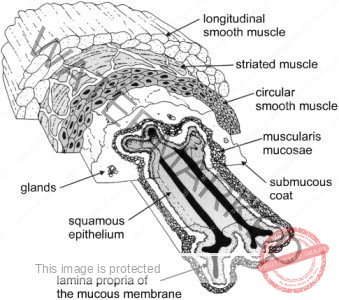

Vagina

Description: The vagina is a muscular canal composed of fibrous tissue, internally lined with a protective non-keratinized stratified squamous epithelium. It acts as the connecting pathway between the external and internal reproductive structures, extending from the body’s exterior up to the cervix of the uterus.

Orientation: It runs in an upward and backward direction, at approximately a 45-degree angle within the pelvis.

Position relative to other organs: It is located between the bladder and urethra in the front and the rectum and anus at the back.

Wall Length Discrepancy: In an adult female, the anterior (front) vaginal wall is approximately 7.5 cm in length, while the posterior (back) wall is slightly longer at about 9 cm. This length difference arises because of the cervix’s angled entry point into the anterior vaginal wall.

Vagina – Structure

The vaginal wall is composed of three distinct layers:

Outer Layer: An external layer consisting of loose connective tissue (areolar tissue), providing support and flexibility.

Muscular Layer: A middle layer made of smooth muscle tissue, responsible for the vagina’s ability to expand and contract.

Inner Lining: The innermost layer is a stratified squamous epithelium, arranged in ridges or folds known as rugae. This lining is non-keratinized, meaning it remains moist and flexible.

Notably, the vagina itself lacks glands that produce secretions. Its moist surface is maintained by fluids originating from the cervix.

A healthy vaginal environment between puberty and menopause is characterized by the presence of Lactobacillus acidophilus bacteria. These bacteria produce lactic acid, which creates an acidic environment with a pH range of 3.5 to 4.9. This acidity acts as a natural defense mechanism, inhibiting the proliferation of most harmful microorganisms that might enter from the perineal area, thus protecting against infection.

Blood Supply: The vagina receives arterial blood through a network of vessels (plexus) formed from branches of the uterine and vaginal arteries. These arteries originate from the internal iliac arteries within the pelvis.

Venous Drainage: Venous blood is drained away from the vagina via a venous plexus located within its muscular wall, flowing into the internal iliac veins.

Vagina – Functions

The vagina serves several crucial roles:

Coitus: It functions as the receiving site for the penis during sexual intercourse, facilitating sperm deposition.

Birth Canal: It provides a distensible channel through which an infant passes during childbirth.

Menstruation: It serves as the route for the elimination of menstrual blood and tissue from the uterus.

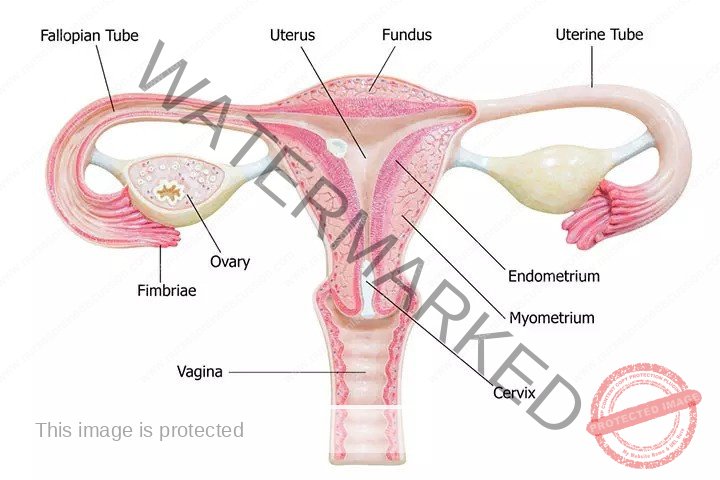

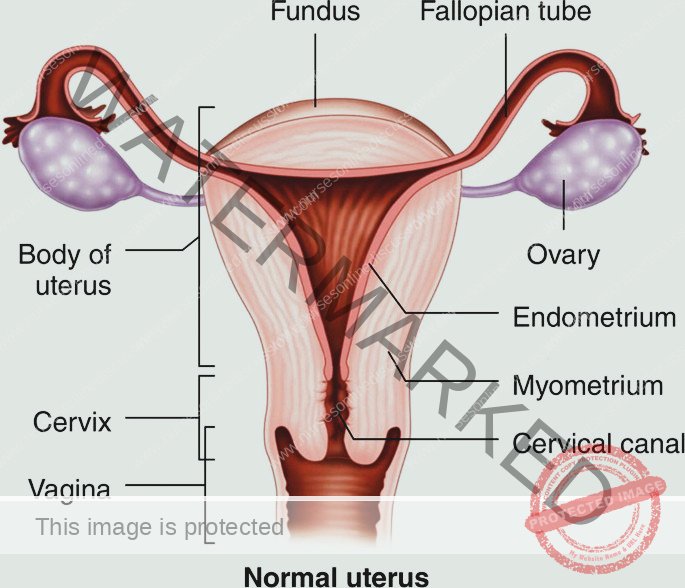

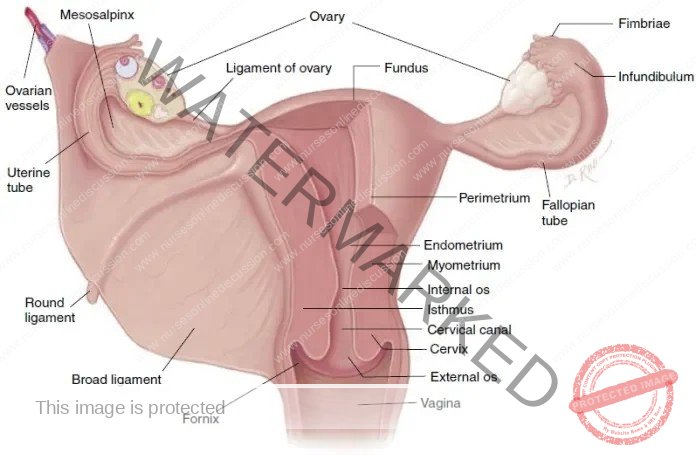

Uterus

Description: The uterus is a hollow organ, shaped like an inverted pear, and somewhat flattened from front to back (anteroposteriorly).

Location: It is positioned centrally within the pelvic cavity, nestled between the urinary bladder (located in front) and the rectum (located behind).

Size and Weight: In a typical non-pregnant adult, the uterus weighs approximately 30-40 grams. It adopts a near-horizontal orientation within the pelvis and has approximate dimensions of:

Length: 7.5 cm

Width: 5 cm

Wall Thickness: 2.5 cm

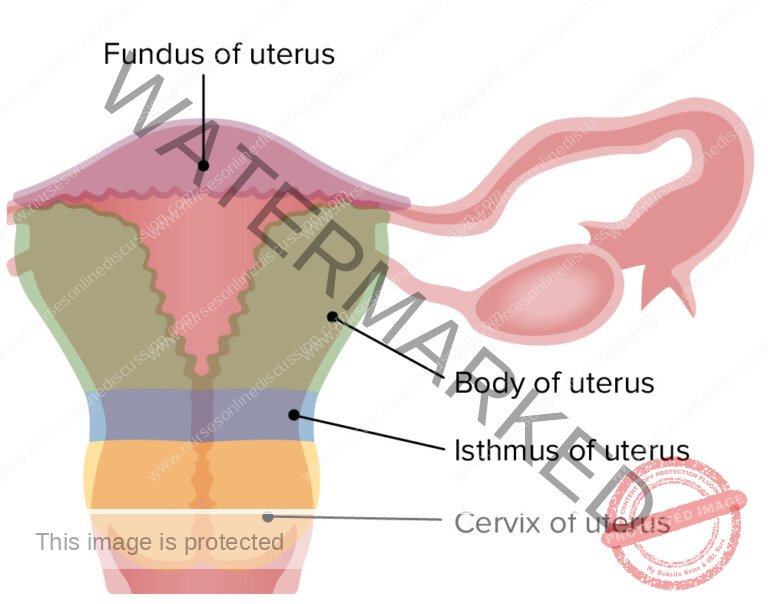

Uterine Parts

The uterus is anatomically divided into distinct regions:

Fundus: This is the rounded, uppermost section of the uterus. It is located above the point where the uterine tubes (Fallopian tubes) connect to the uterus. Think of it as the dome or top portion.

Body (Corpus): The body constitutes the major and broadest part of the uterus. It tapers downwards towards the cervix. The narrowing point where the body transitions into the cervix is known as the internal os (internal opening).

Cervix: Often referred to as the “neck” of the uterus, the cervix is the lowermost, cylindrical portion. It projects into the vagina, penetrating the anterior vaginal wall. The opening of the cervix into the vagina is called the external os (external opening).

Isthmus: This is a short, constricted segment, approximately 1 cm in length. It acts as a transitional zone situated between the body of the uterus and the cervix. It is a less defined region compared to the other parts.

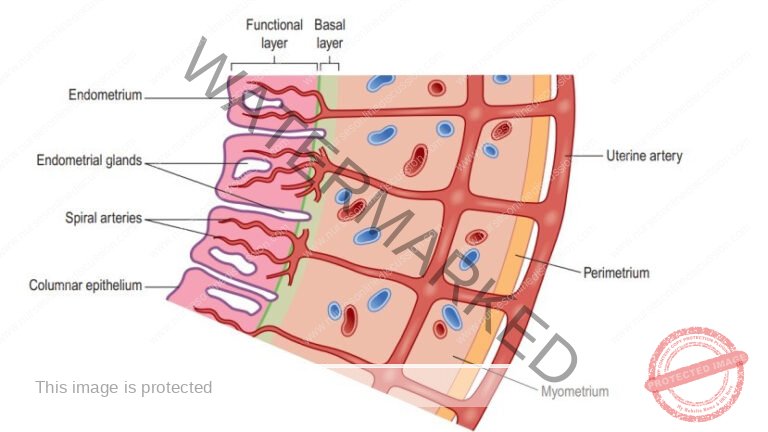

Uterine Structure

The uterine wall is composed of three distinct tissue layers:

Perimetrium: This is the outermost serous layer, essentially a visceral peritoneum. It envelops the fundus, body, and cervix of the uterus. Anteriorly, it forms the vesicouterine pouch (a space between the uterus and bladder), and posteriorly, it creates the rectouterine pouch (Pouch of Douglas – a space between the uterus and rectum). Laterally, the broad ligament, which anchors the uterus to the pelvic walls, is formed from the perimetrium.

Myometrium: The middle and most substantial layer of the uterine wall. It is primarily made up of thick smooth muscle bundles interwoven with connective tissue (areolar tissue), blood vessels, and nerves. This muscular layer is crucial for uterine contractions.

Endometrium: The innermost mucosal lining of the uterus. It consists of a columnar epithelium containing tubular glands that secrete mucus. Functionally, the endometrium is differentiated into two layers:

Functional Layer (Stratum Functionalis): The superficial layer closest to the uterine cavity. This layer is responsive to hormonal changes during the menstrual cycle and is shed during menstruation if fertilization does not occur.

Basal Layer (Stratum Basalis): The deeper layer, adjacent to the myometrium. This layer is responsible for regenerating the functional layer after each menstruation cycle, ensuring the endometrium is rebuilt. The upper portion of the cervical canal is also lined by this mucous membrane.

Vascular Supply

Arterial Supply: The uterus receives its arterial blood supply from the uterine arteries. These arteries originate as branches from the internal iliac arteries and ascend along the sides of the uterus, positioned between the layers of the broad ligaments to reach the organ.

Venous Drainage: Venous blood from the uterus is drained via a network of veins that generally follow the same pathway as the arteries, eventually emptying into the internal iliac veins.

Functions of the Uterus

The uterus plays vital roles in reproduction:

Menstrual Cycle Preparation: The uterus undergoes cyclical changes (the menstrual cycle) to prepare the endometrial lining to receive and nurture a fertilized egg.

Implantation: It provides the site where a fertilized ovum (zygote) implants and begins development within the endometrium.

Ovum Nourishment: The uterus secretes fluids that provide nourishment to the ovum both before and after it implants into the endometrial lining.

Placenta Formation: The uterine wall serves as the attachment site for the placenta, the organ that facilitates nutrient and waste exchange between mother and fetus.

Childbirth (Labour): During childbirth, the powerful muscular contractions of the myometrium are responsible for expelling the baby from the uterus through the birth canal.

Supporting Structures of the Uterus

The uterus is securely positioned within the pelvic cavity through a combination of support from surrounding organs, the pelvic floor musculature, and a network of ligaments that anchor it to the pelvic walls. Key supportive structures include:

Broad Ligaments:

Description: These are double layers of peritoneum (the membrane lining the abdominal cavity) that extend from each side of the uterus, creating wing-like folds.

Position: They drape over the uterine tubes and extend laterally to attach to the pelvic sidewalls.

Uterine Tube Enclosure: The uterine tubes are located within the upper, free edge of the broad ligaments. They penetrate the posterior layer of the ligament near its outer edge to open into the abdominal cavity.

Ovarian Attachment: The ovaries are connected to the posterior surface of the broad ligaments, one on each side.

Vascular and Nerve Pathway: Blood vessels, lymphatic vessels, and nerves reach the uterus and uterine tubes by passing between the layers of the broad ligaments, providing essential supply and control.

Round Ligaments:

Description: These are bands of fibrous connective tissue situated between the two layers of the broad ligament on both sides of the uterus.

Course: They extend towards the sides of the pelvis, travel through the inguinal canal (a passageway in the groin), and ultimately blend into the tissue of the labia majora.

Utero-sacral Ligaments:

Origin: These ligaments arise from the posterior aspect of the cervix and upper vagina.

Direction: They run backwards, one on each side of the rectum, towards the sacrum (the triangular bone at the base of the spine), where they attach.

Transverse Cervical (Cardinal) Ligaments:

Connection Points: These ligaments extend from the lateral sides of the cervix and vagina to the side walls of the pelvis.

Support Function: They provide significant lateral support to the cervix and uterus.

Pubo-cervical Fascia:

Origin & Direction: This fascial layer extends forward from the transverse cervical ligaments on each side, towards the bladder.

Attachment Point: It attaches to the posterior (back) surface of the pubic bones, contributing to anterior support of the cervix and bladder base.

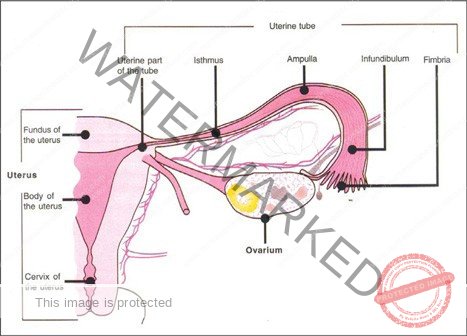

Fallopian Tubes (Uterine Tubes)

Length and Location: The uterine tubes, also known as Fallopian tubes, are approximately 10 cm long. They extend outwards from the uterus, originating at the junction of the uterine body and fundus (the upper part of the uterus).

Broad Ligament Position: These tubes are situated within the upper free edge of the broad ligament, a supportive fold of peritoneum.

Lateral Ends & Fimbriae: The outer ends of the tubes are funnel-shaped or trumpet-like. These ends pierce through the posterior layer of the broad ligament and open into the peritoneal cavity, positioning them near the ovaries. The opening of each tube is surrounded by finger-like projections called fimbriae.

Ovarian Fimbria: One fimbria, known as the ovarian fimbria, is longer than the others and maintains a close association with the ovary. This fimbria helps to guide the released ovum into the uterine tube.

Function: The Fallopian tubes serve as a vital conduit. They provide the pathway for sperm to travel towards an ovum, and they also facilitate the transport of secondary oocytes (eggs) and fertilized ova (zygotes) from the ovaries to the uterine cavity.

Fallopian Tube Parts

The Fallopian tube is segmented into distinct regions:

Fimbriae End: The distal, ovarian end of the tube characterized by finger-like extensions.

Infundibulum: A funnel-shaped opening of the tube closest to the ovary, which communicates with the pelvic cavity.

Ampulla: The longest and widest segment, forming roughly the outer two-thirds of the tube.

Isthmus: The proximal, shorter, and narrower segment near the uterus, marked by thicker walls. It connects the ampulla to the uterus.

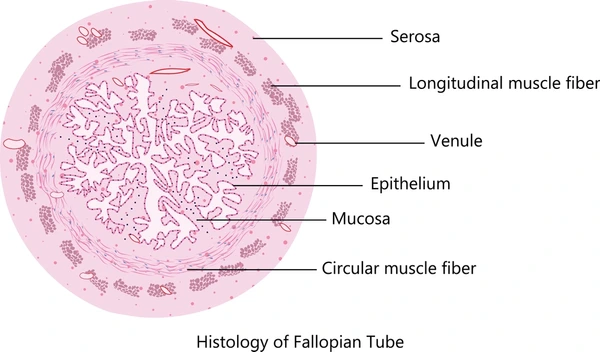

Fallopian Tube Structure

The uterine tubes, also known as Fallopian tubes, are characterized by a three-layered structure:

Outer Layer (Serosa/Peritoneum): An external covering derived from the broad ligament, which is essentially peritoneum.

Muscular Layer (Muscularis): A middle layer composed of smooth muscle, essential for tube movement. This layer has:

Inner Circular Layer: A thicker ring of smooth muscle fibers oriented circularly.

Outer Longitudinal Layer: A thinner layer of smooth muscle fibers oriented longitudinally.

Inner Lining (Mucosa): The innermost layer consisting of ciliated epithelium. This lining includes:

Ciliated Columnar Cells: Simple columnar cells with cilia that create a “ciliary current”. This current assists in moving the oocyte or fertilized ovum towards the uterus.

Peg Cells (Non-ciliated): Non-ciliated cells with microvilli that secrete a nourishing fluid for the ovum.

The coordinated action of peristaltic muscle contractions in the muscularis and the ciliary beating of the mucosal epithelium propels the oocyte or zygote towards the uterus. During ovulation, the fimbriae’s motion generates local currents, guiding the released secondary oocyte from the pelvic cavity into the uterine tube. Fertilization typically takes place in the ampulla of the uterine tube, although it can occasionally occur in the pelvic cavity.

Fallopian Tube Functions

The uterine tubes perform key roles in reproduction:

Ovum Transport: They facilitate the movement of the ovum from the ovary to the uterus through a combination of peristaltic contractions and ciliary action.

Mucus Secretion for Gamete Support: The mucosal lining secretes mucus that creates a favorable environment for both ovum and sperm movement and survival.

Usual Fertilization Site: The uterine tube is the typical location where fertilization of the ovum by sperm occurs. After fertilization, the resulting zygote is then transported to the uterus for implantation.

Ovaries

Primary Function: The ovaries serve as the female gonads, with the crucial roles of producing female sex hormones and developing ova (eggs).

Location: They are positioned within shallow depressions, known as ovarian fossae, located on the side walls of the pelvic cavity.

Size: Ovaries are relatively small organs, typically measuring:

Length: 2.5 to 3.5 cm

Width: 2 cm

Thickness: 1 cm

Homology: In terms of development and function, the ovaries are considered analogous to the testes in males.

Ligamentous Attachments: Each ovary is anchored in place by ligaments:

Ovarian Ligament: Connects the ovary to the upper region of the uterus.

Mesovarium: A wider band of tissue that attaches the ovary to the posterior side of the broad ligament. Blood vessels and nerves reach the ovary through this mesovarium.

Ovary Ligaments and Attachment

Broad Ligament and Mesovarium: The broad ligament, a fold of the parietal peritoneum, indirectly connects to the ovaries via a double layer of peritoneum called the mesovarium.

Ovarian Ligament Function: This ligament specifically anchors the ovary to the uterus itself, providing medial support.

Suspensory Ligament: This ligament extends from the ovary to the pelvic wall, offering lateral support.

Hilum: Each ovary possesses a hilum, which is the point where blood vessels and nerves enter and exit the ovary. The mesovarium is attached to the ovary at this hilum region.

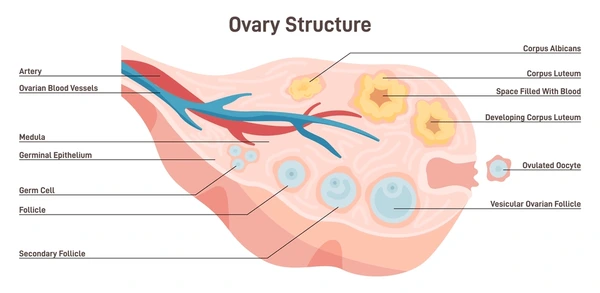

Ovary Structure

The ovary is composed of two primary zones:

Medulla:

Location: Situated centrally within the ovary.

Composition: Primarily consists of connective tissue, including fibrous elements, alongside blood vessels and nerves that supply the organ.

Cortex:

Location: The outer region that surrounds the central medulla.

Components: Characterized by a supporting framework of connective tissue known as the stroma, which is externally covered by a layer of cells previously termed “germinal epithelium”.

Ovarian Follicles: The cortex is the site of ovarian follicles, which are present at various stages of development. Each follicle contains an oocyte (developing ovum).

Pre-puberty State: Before puberty, the ovaries are in a relatively inactive state. However, the stroma already contains primordial follicles, which are immature follicles present from birth.

Ovulation Cycle: During the reproductive years, typically around every 28 days, one ovarian follicle, known as a Graafian follicle (mature follicle), undergoes maturation. This follicle ruptures and releases its ovum into the peritoneal cavity in a process termed ovulation.

Corpus Luteum & Corpus Albicans: Following ovulation, the remnants of the ruptured follicle transform into the corpus luteum, a temporary endocrine structure recognizable as a “yellow body”. If pregnancy does not occur, the corpus luteum degenerates and leaves behind a small, permanent scar of fibrous tissue on the ovarian surface called the corpus albicans, known as a “white body”.

Ovary Vascular Supply

Arterial Supply: Oxygenated blood is delivered to the ovaries via the ovarian arteries. These arteries branch directly from the abdominal aorta, originating just below the level of the renal arteries.

Venous Drainage: Deoxygenated blood is drained from the ovaries through a network of veins forming a plexus located behind the uterus. This plexus gives rise to the ovarian veins. The right ovarian vein empties into the inferior vena cava, the body’s largest vein. In contrast, the left ovarian vein drains into the left renal vein, which then connects to the inferior vena cava.

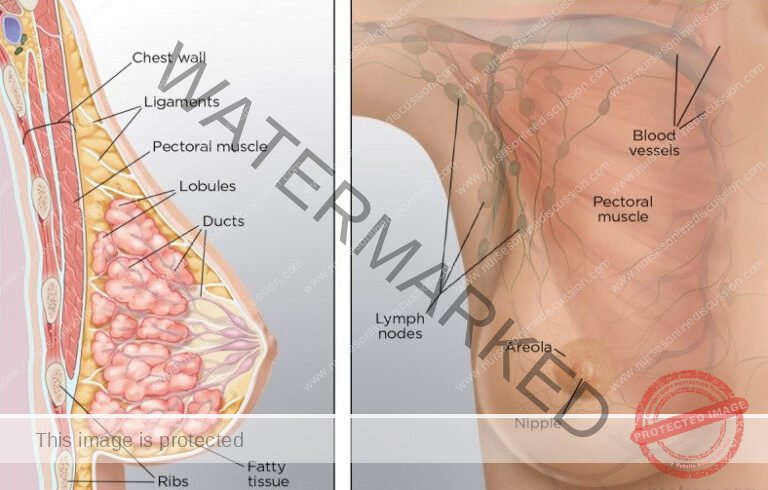

Mammary Glands/Breasts

The mammary glands, commonly known as breasts, are considered accessory organs of the female reproductive system. While present in both sexes, they are functional and significantly developed in females.

Each breast is a dome-shaped structure of varying size, situated on the anterior chest wall. They are positioned superficial to the pectoralis major and serratus anterior muscles and are connected to these muscles by a layer of dense, irregular connective tissue fascia.

Breast Anatomy

Key anatomical features of the breast include:

Nipple: A pigmented, raised projection at the apex of each breast. It is perforated by multiple small openings, the lactiferous duct pores, which serve as the exit points for milk during lactation.

Areola: The circular zone of pigmented skin surrounding the nipple. The areolar surface appears somewhat textured due to the presence of specialized sebaceous glands (areolar glands), which secrete oil.

Suspensory Ligaments (Cooper’s ligaments): Fibrous connective tissue strands that extend from the skin inwards to the underlying fascia. These ligaments provide structural support to the breast tissue. Their elasticity can diminish with age or repetitive high-impact stress, such as in activities like long-distance running or intense aerobics. Wearing a supportive bra can help to mitigate strain on these ligaments and maintain breast support over time.

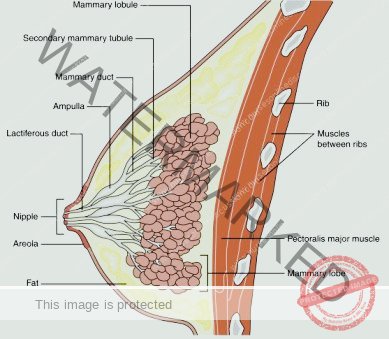

Mammary Gland Structure

Each breast contains a mammary gland, the functional unit responsible for producing milk.

Lobular Organization: The mammary gland is organized into 15 to 20 lobes. These lobes represent distinct sections of the gland, separated from each other by varying quantities of adipose tissue (fat).

Lobules and Alveoli: Within each lobe, there are smaller units called lobules. Lobules are composed of clusters of alveoli, which are grape-like sacs of milk-secreting cells. These alveoli are embedded within connective tissue.

Myoepithelial Cell Function: Surrounding each alveolus are myoepithelial cells. These specialized cells contract to squeeze the alveoli, facilitating the movement of milk towards the nipple.

Milk Duct System: Milk produced in the alveoli flows into secondary tubules, which then converge into larger mammary ducts.

Lactiferous Sinuses and Ducts: Close to the nipple, the mammary ducts widen to form lactiferous sinuses. These sinuses act as reservoirs where a small amount of milk can be stored temporarily. From the sinuses, milk drains into lactiferous ducts.

Milk Delivery: Each lactiferous duct originates from a single lobe and terminates at the nipple. These ducts provide individual pathways for milk to be transported from each lobe to the exterior for breastfeeding.

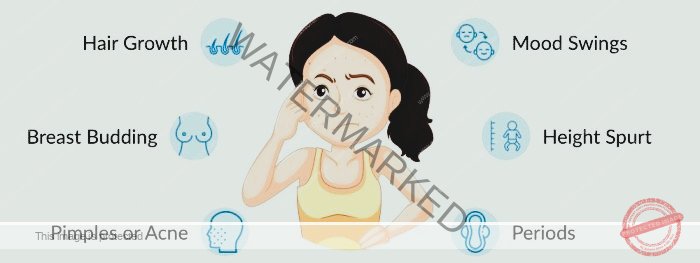

Female Puberty

Puberty in females marks the stage of sexual maturation when reproductive organs become fully functional, generally occurring between the ages of 12 and 14 years. The first menstrual period, known as menarche, signals the beginning of a woman’s reproductive years. This process of ovarian development is driven by gonadotropic hormones released from the anterior pituitary gland, specifically follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH).

Key Developmental Changes During Female Puberty:

Maturation of Reproductive Organs: The uterus, fallopian tubes, and ovaries complete their development, becoming ready for their functions in reproduction.

Initiation of Menstrual Cycles & Ovulation (Menarche): The onset of menstruation and the release of eggs (ovulation) begins, marking reproductive capability.

Breast Development and Enlargement: The breasts undergo noticeable growth and structural changes.

Appearance of Pubic and Axillary Hair: Hair growth in the pubic and underarm areas develops as secondary sexual characteristics emerge.

Increase in Stature and Pelvic Girdle Widening: A growth spurt in height occurs, and the pelvis broadens to accommodate potential pregnancy and childbirth.

Changes in Fat Distribution: Subcutaneous fat deposition increases, particularly around the hips and breasts, contributing to a more feminine body shape.

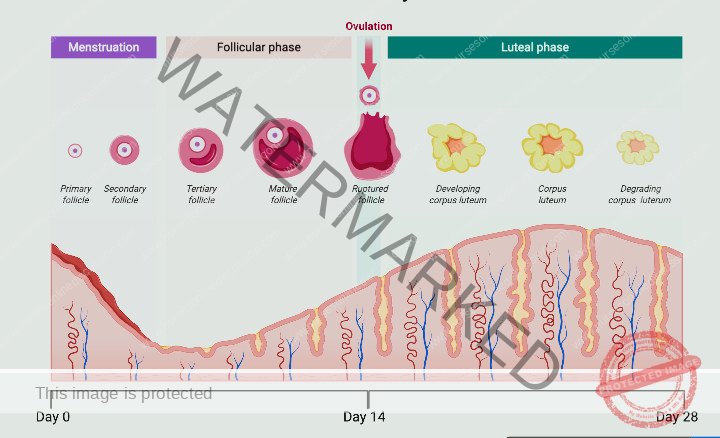

The Reproductive Cycle in Females

The female reproductive cycle is a recurring sequence of events that typically occurs every 26 to 30 days throughout a woman’s fertile period, from menarche to menopause. This cycle involves coordinated changes in both the ovaries and the uterine lining. These changes are orchestrated by fluctuations in hormone levels within the bloodstream.

Hormonal Control:

The hypothalamus initiates the cycle by releasing luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH). This hormone, in turn, stimulates the anterior pituitary gland to secrete two key hormones: follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH).

FSH Function: Follicle-stimulating hormone primarily promotes the development and maturation of ovarian follicles within the ovaries. It also stimulates the follicles to produce and secrete oestrogen.

LH Function: Luteinizing hormone plays a critical role in triggering ovulation, the release of a mature egg from an ovarian follicle. After ovulation, LH supports the development and maintenance of the corpus luteum.

Menstrual Phase

Hormonal Decline: If fertilization does not occur, the corpus luteum breaks down. This degeneration causes a reduction in the levels of both oestrogen and progesterone hormones.

Endometrial Shedding: The functional layer of the endometrium, which requires oestrogen and progesterone to maintain its structure, is shed. This shedding is menstruation.

Menstrual Flow Composition: The menstrual discharge consists of endometrial tissue secretions, cellular debris, blood, and the unfertilized egg cell.

Proliferative Phase

Follicle Stimulation: Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH) stimulates an ovarian follicle to grow and mature. This follicular growth leads to the production of oestrogen.

Endometrial Build-up: Oestrogen initiates the proliferative phase by causing the functional layer of the endometrium to thicken and rebuild. This prepares the uterine lining for potential implantation of a fertilized egg.

Ovulation Trigger: Increasing levels of oestrogen reach a threshold that triggers a surge in Luteinizing Hormone (LH). This LH surge causes ovulation, marking the end of the proliferative phase.

Secretory Phase

Corpus Luteum Formation: Following ovulation, Luteinizing Hormone (LH) promotes the development of the corpus luteum from the ruptured follicle. The corpus luteum then starts producing progesterone, along with oestrogen and inhibin.

Endometrial Secretory Changes: Progesterone drives changes within the endometrium, enhancing the secretory activity of endometrial glands. These changes create an environment conducive to implantation and also facilitate the movement of sperm within the female reproductive tract.

Cervical Mucus Changes: Cervical mucus becomes more abundant and less viscous, which aids the passage of sperm. These changes in cervical mucus, along with other physiological signs, can be indicators of ovulation.

Fertilization and Pregnancy

Ovum Viability: The ovum is only capable of being fertilized for a short period after ovulation (potentially as short as 8 hours).

Sperm Survival: Sperm cells can survive for a longer duration within the female reproductive tract.

Implantation and hCG Production: If fertilization happens, the zygote (fertilized egg) travels to the uterus and implants into the endometrium. The implanted embryo begins to produce human Chorionic Gonadotropin (hCG).

Corpus Luteum Maintenance: hCG signals the corpus luteum to continue functioning and producing progesterone and oestrogen. This hormonal support is crucial for maintaining the early stages of pregnancy.

Prevention of Follicle Maturation: The hormonal environment of early pregnancy, maintained by the corpus luteum, placenta, and gonadotrophins, prevents the maturation of new ovarian follicles, thus halting the regular menstrual cycle.

Get in Touch

(+256) 790 036 252

(+256) 748 324 644

Info@nursesonlinediscussion.com

Kampala ,Uganda

© 2025 Nurses online discussion. All Rights Reserved Design & Developed by Opensigma.co