Respiratory System Conditions

Subtopic:

Haemophilus influenza Infection

Haemophilus influenza

Haemophilus influenzae is identified as a gram-negative bacterium, exhibiting a coccobacillus morphology and categorized within the Coccobacilli group. This bacterium is a facultative anaerobe and commonly exists as a commensal organism residing in the nasal and throat regions. Under typical healthy conditions, it does not provoke infection. However, in instances of weakened host defenses, H. influenzae can transition to a pathogenic state. Historically, it was mistakenly considered the etiological agent of influenza, which is now accurately attributed to the influenza virus.

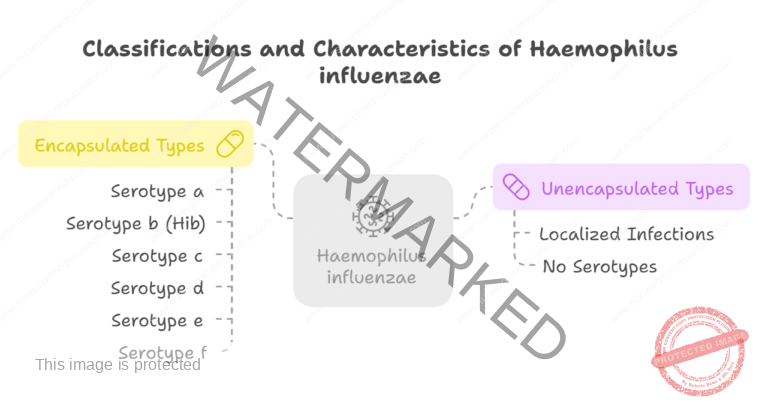

Classifications of Haemophilus Influenzae

Haemophilus influenzae is categorized into two primary classes determined by the presence or absence of a polysaccharide capsule: Encapsulated and Unencapsulated (also termed non-typeable).

Encapsulated Types:

Comprise six distinct serotypes, designated a through f. These classifications are based on variations in their capsular antigens, for example, Haemophilus influenzae type a, b, c, d, e, and f.

Serotype b (Hib) is particularly significant as it is the most common and main cause of severe invasive infections.

Vaccination is effective against encapsulated strains, most notably with the Hib vaccine, which targets type b.

Unencapsulated Types (Non-typeable):

Lack a polysaccharide capsule and therefore do not have serotypes.

Generally considered less invasive compared to encapsulated types.

Can still induce localized infections and inflammation in areas like the respiratory tract or ears.

Hib vaccine does not offer protection against these non-typeable strains.

Infections and Diseases:

Infections caused by Haemophilus influenzae manifest in a range of illnesses, especially when the bacteria overcomes the body’s defenses. These conditions include:

Invasive Diseases: (Typically associated with Encapsulated strains)

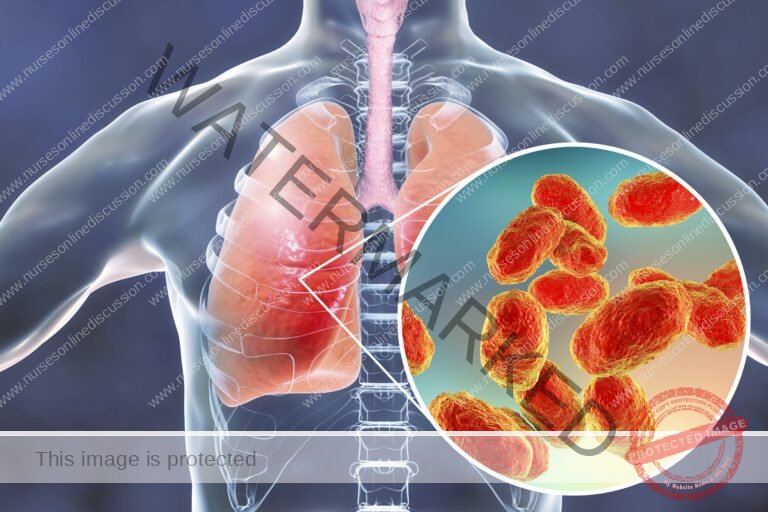

Pneumonia: Lung infection.

Bacteremia: Presence of bacteria in the bloodstream.

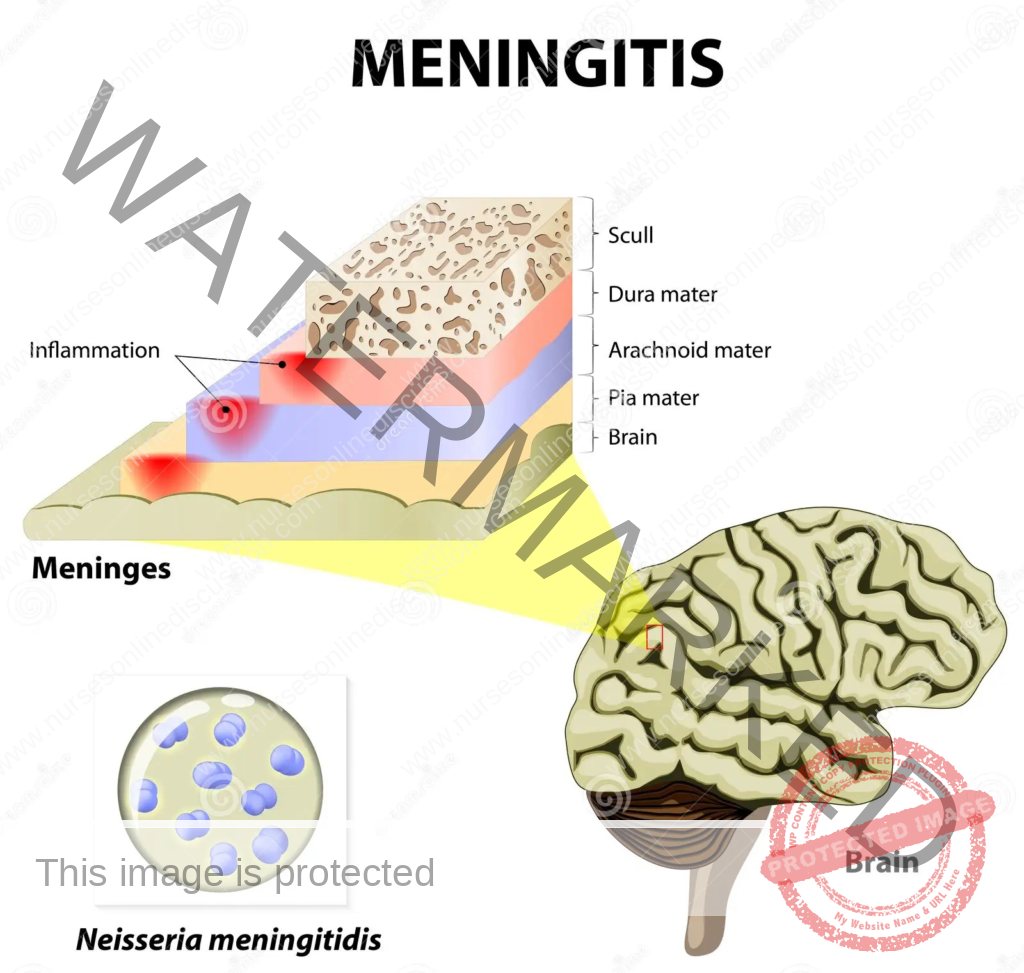

Meningitis: Inflammation of the membranes surrounding the brain and spinal cord.

Epiglottitis: Inflammation of the epiglottis, the flap at the base of the tongue.

Cellulitis: Skin and soft tissue infection.

Infectious Arthritis: Joint infection.

Osteomyelitis: Bone infection.

and other conditions.

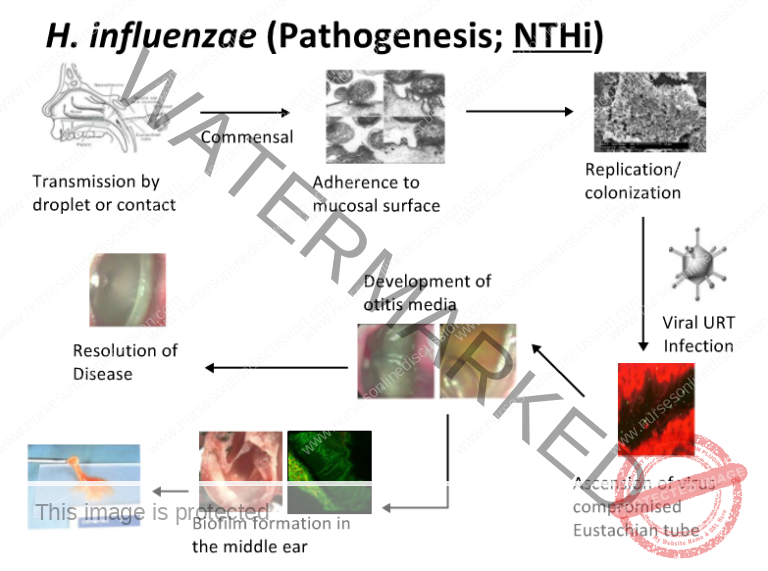

Non-invasive Diseases: (Typically associated with Non-encapsulated strains)

Otitis Media: Middle ear infection.

Conjunctivitis: Inflammation of the conjunctiva (pink eye).

Mode of Spread of Haemophilus Influenzae

The primary transmission method for Haemophilus influenzae is through respiratory droplets from person to person. The bacteria spreads when an infected individual coughs or sneezes, expelling microscopic droplets carrying the pathogen into the surrounding air. These droplets can then be inhaled by individuals nearby, resulting in the colonization of their respiratory system.

Respiratory Droplet Transmission: The most frequent way the bacteria spreads is via airborne droplets produced when infected individuals cough, sneeze, or even talk.

Close Proximity: Transmission is more likely to occur when individuals are in close physical proximity to an infected person, especially in crowded or enclosed environments.

Asymptomatic Carriers: Individuals who carry Haemophilus influenzae but show no symptoms can still potentially transmit the bacteria to others.

Opportunistic Pathogen: Haemophilus influenzae is considered an opportunistic agent, meaning it can cause infection when the body’s defenses are weakened. It can reside in the respiratory tract without causing illness in healthy people, but may lead to infections if the host’s immune system is compromised.

Vulnerable Age Groups: Transmission is especially relevant in settings with many young children, as they are more susceptible to certain severe Haemophilus influenzae infections, notably Hib (type b) meningitis.

Risk Factors for Hib Disease:

Household Crowding: Living in densely populated households increases the likelihood of person-to-person spread via respiratory droplets, elevating the risk of Hib infection.

Large Family Size: Larger families present more opportunities for infectious agents to spread. Increased household members raise the probability of someone carrying Haemophilus influenzae, thus increasing transmission risk.

Childcare Attendance: Children attending daycare or preschool experience closer contact with peers, which facilitates bacterial spread. Furthermore, young children’s immune systems are still developing, making them more vulnerable to infections like Hib.

Lower Socioeconomic Status: Reduced socioeconomic status is often linked to limited access to healthcare, crowded living conditions, and potential difficulties in maintaining hygiene. These combined factors contribute to a higher risk of Hib infection.

Lower Parental Education Levels: Parents with less formal education may have reduced awareness regarding preventative healthcare measures. This lack of knowledge can affect their capacity to protect their children from infectious diseases, including Hib.

School-Age Siblings: Siblings attending school can be exposed to various infectious agents, including Haemophilus influenzae. As carriers, they can potentially transmit the bacteria to younger siblings at home.

Age (Young and Old): Very young children and the elderly are at increased risk. Young children often have immature immune systems, while older adults may have declining immunity, making both groups more susceptible to severe infections.

Race/Ethnicity (Certain Groups): Specific populations, like Native Americans, may face higher risks due to a mix of genetic predispositions, socioeconomic factors, and healthcare access disparities that can contribute to a higher incidence of Hib disease.

Chronic Illnesses: Conditions that weaken the immune system, such as HIV, immunodeficiency disorders, or asplenia, diminish the body’s ability to combat infections, raising both the risk and severity of Hib disease.

Premature Birth: Premature infants may have underdeveloped immune systems, placing them at greater risk of infections, including Hib. Their immune systems may be less equipped to effectively respond to bacterial threats.

Age Extremes: Individuals at the youngest (under 5 years) and oldest (over 65 years) age ranges often exhibit weaker immune responses, making them more susceptible to severe infections, including those caused by Haemophilus influenzae.

Immunocompromised Individuals: People with weakened immune systems, such as those with HIV/AIDS, cancers, or sickle cell disease, are less able to mount an effective immune response against pathogens, increasing the risk of severe Hib infections.

Asplenia: Absence or dysfunction of the spleen (asplenia) impairs the immune system’s ability to clear bacteria from the bloodstream, leading to an elevated risk of severe Hib infections.

Pathophysiology of Haemophilus Influenzae Infection:

Initial Entry:

Haemophilus influenzae typically gains entry to the body via the nasopharynx, the upper portion of the respiratory tract.

Nasopharyngeal Colonization: The bacteria then establishes itself in the nasopharynx. This colonization can be transient or persist for extended periods, even months. Some individuals become asymptomatic carriers, harboring the bacteria without showing any signs of illness.

Proliferation and Immune Detection:

Bacterial Multiplication: Upon entering the body, H. influenzae begins to reproduce and increase in number.

Immune System Activation: The body’s defense system recognizes the bacteria as a foreign entity, triggering an immune response. Immune cells become alerted to the potential threat.

Inflammatory Response:

Immune Cell Mobilization: The immune system reacts by dispatching various immune cells, along with signaling molecules like cytokines, to the site of infection. This is a defensive action to counteract the invading bacteria.

Inflammation Development: As immune cells interact with the bacteria, inflammation ensues. This is a protective biological response intended to eliminate the infectious agent.

Signs and Symptoms Emerge:

Manifestation of Symptoms: The inflammatory process results in the appearance of typical infection signs and symptoms. These can include fever, fatigue, nausea, and other systemic symptoms, reflecting the body’s efforts to fight off the infection.

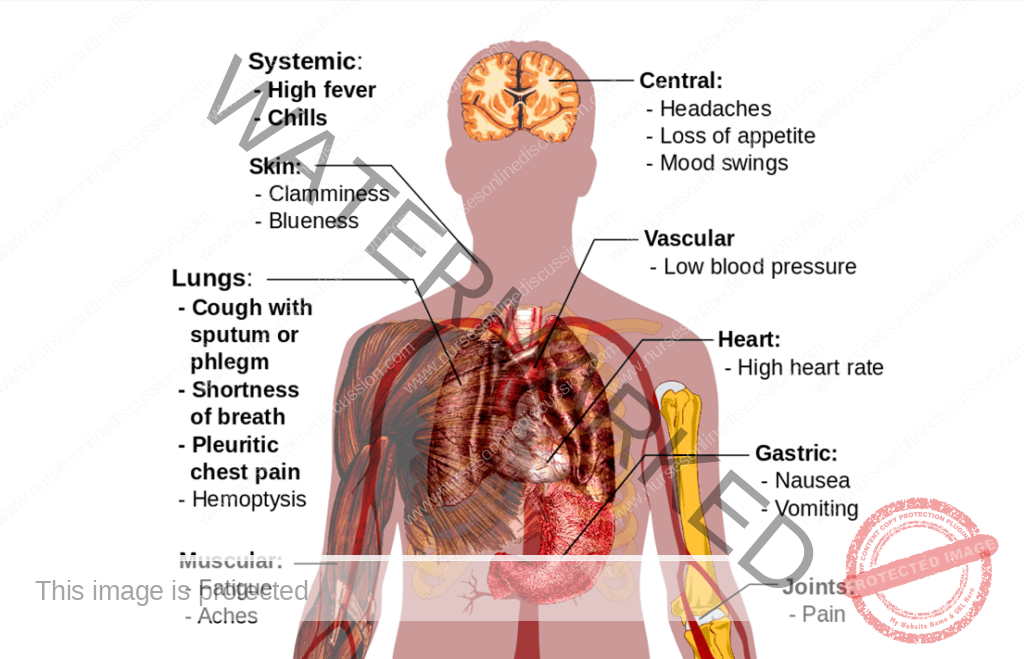

Clinical Manifestations of Pneumonia

Clinical Features according to Infections and Diseases

Clinical Manifestations

Pneumonia:

Characterized by fever and chills.

Presence of cough.

Experience of shortness of breath.

Sweating episodes.

Chest discomfort or pain.

May include headache.

Bacteremia:

General feeling of being unwell and fatigue.

Fever and chills are typical.

Marked tiredness.

Loss of appetite (anorexia).

Symptoms like nausea and vomiting can occur.

Difficulty breathing (dyspnea).

Potential for confusion or altered mental state.

Increased irritability.

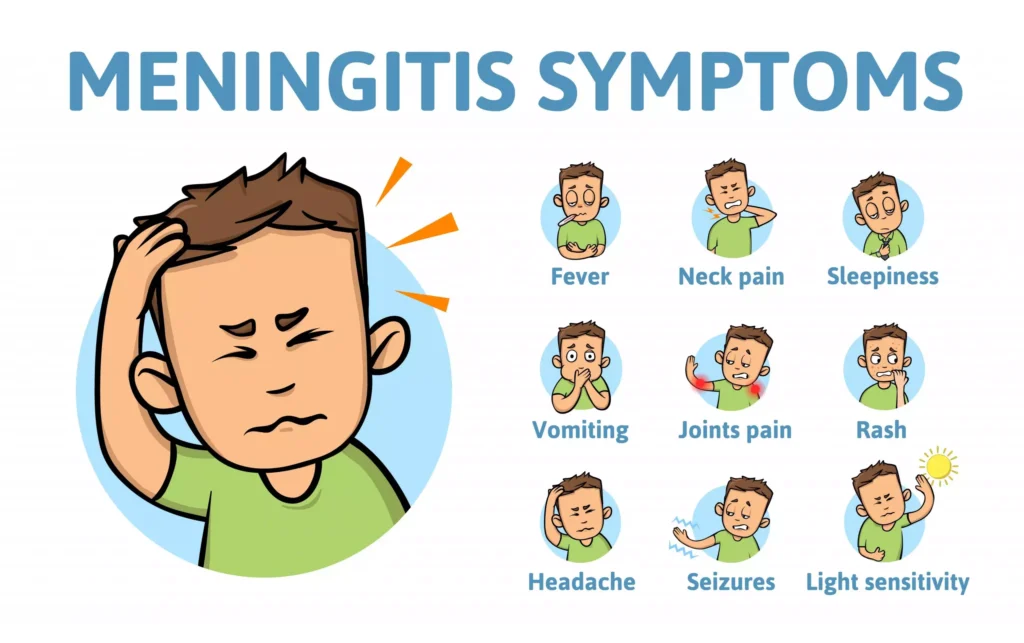

Meningitis:

In children, may present with:

Unusual irritability.

Vomiting after feeding or during feeds.

Headache (if the child can express it).

Stiff neck.

Nausea and potentially vomiting.

Sensitivity to light (photophobia).

Confusion or reduced level of consciousness.

Possible long-term effects in survivors include hearing loss or neurological complications.

Carries a case fatality ratio of 3% to 6%.

Epiglottitis:

Involves infection and swelling of the epiglottis.

Presents a life-threatening risk of airway obstruction.

Signs and Symptoms may include:

Poor feeding and refusal to eat.

Reduced engagement and lack of activity.

General weakness.

Drowsiness.

Reduced reflexes in infants.

Diagnosis and Investigations

Clinical Evaluation:

Patient History: Obtain details about the patient’s current symptoms, recent health issues, and potential exposure risks for infection.

Physical Exam: Conduct a comprehensive physical examination to identify specific signs and symptoms related to the suspected infection site, for instance, listening to lung sounds for pneumonia or checking for neck stiffness in meningitis cases.

Laboratory Analyses:

Gram Stain Technique: Employ Gram staining to visualize bacterial morphology. Examination of Gram-stained samples from infected sites may reveal small, gram-negative coccobacilli, suggestive of H. influenzae.

Microbial Culture: Collect specimens such as CSF, blood, pleural fluid, joint fluid, or middle ear aspirates for culture. The aim is to grow and definitively identify H. influenzae. A positive culture confirms the diagnosis. Antigen or DNA detection methods can be supplementary, especially if the patient has received partial antibiotic treatment.

Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF) Analysis: For suspected meningitis, perform a lumbar puncture to obtain CSF. Analyze the CSF for the presence of bacteria, elevated white blood cell count, and other infection indicators.

Sputum Culture: In pneumonia cases, collect a sputum sample for culture to identify the causative agent, including Haemophilus influenzae.

Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR): Utilize molecular techniques like PCR to identify the specific strain of Haemophilus influenzae, providing detailed information for tailored treatment strategies.

Imaging Assessments:

Chest Radiography: For suspected pneumonia, a chest X-ray can be used to visualize lung abnormalities and support the diagnosis.

Management

Therapeutic Goals:

Minimize the risk of further complications.

Alleviate pain and discomfort.

Sustain life functions.

Enhance patient comfort.

Immediate Actions:

Receive and admit the patient and accompanying family members to the appropriate medical ward. For meningitis cases, admit the patient to a single isolation room with subdued lighting, ensuring a comfortable bed and body position.

Medical Treatment:

Antimicrobial Therapy:

Antibiotic Selection: Initiate first-line treatment promptly using effective third-generation cephalosporins like cefotaxime or ceftriaxone. An alternative approach involves using chloramphenicol in combination with ampicillin.

Treatment Duration: A standard course of antibiotic therapy typically lasts for 10 days in severe infections. For penicillin-resistant strains, consider alternative antibiotics such as ceftriaxone, fluoroquinolones, or macrolides.

Oxygen Support: Administer oxygen therapy as clinically indicated, especially in cases of breathing difficulties or pneumonia.

Fluid Management: Maintain adequate hydration through intravenous fluid administration, which is critical, particularly in severe infections where fluid losses may occur.

Additional Supportive Care: Depending on disease severity and affected organs, supplementary measures may include pain relievers for pain, fever reducers for fever, and anti-nausea medication for nausea and vomiting.

Patient Monitoring: Regularly monitor vital signs, blood pressure levels, and oxygen saturation to evaluate treatment effectiveness.

Vaccination Strategy: Administer the Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) vaccine as a preventive measure, particularly for at-risk populations, to decrease the incidence of invasive Hib disease.

Nursing Care

Admission and Initial Evaluation:

Vital Sign Monitoring: Regularly check and record vital signs, including body temperature, heart rate, breathing rate, and blood pressure.

Comprehensive Assessment: Perform a detailed initial assessment to determine the severity of symptoms and identify affected body systems.

Infection Control Protocols:

Implement standard infection control measures to prevent the spread of infection.

Apply isolation precautions as needed based on the specific type of infection.

Hydration and Nutritional Support:

Administer intravenous fluids as prescribed to maintain proper hydration levels.

Encourage and monitor oral fluid intake if the patient can tolerate it.

Collaborate with a dietitian to provide appropriate nutrition, considering any dietary needs or preferences.

Medication Administration Management:

Administer prescribed antibiotics promptly and according to instructions.

Monitor for any potential adverse reactions to medications.

Respiratory Assistance:

Provide supplemental oxygen as prescribed for patients experiencing respiratory distress or pneumonia.

Closely monitor respiratory status and administer respiratory treatments as necessary.

Pain Alleviation Strategies:

Assess and manage pain using suitable pain management techniques.

Administer pain-relieving medications as prescribed.

Fever Reduction Measures:

Implement strategies to manage fever, such as administering fever-reducing medications as ordered.

Use physical cooling methods (like cool compresses or fans) if required.

Neurological Observation:

For meningitis cases, closely monitor neurological status.

Assess for indicators of increased pressure within the skull.

Emotional Support Provision:

Offer emotional support to both the patient and their family, addressing any concerns or fears they may have.

Keep family members informed about the patient’s condition and the planned treatment.

Patient and Family Education:

Educate the patient and family about the nature of the infection, the treatment plan, and the importance of completing the entire course of prescribed antibiotics.

Provide information on preventive measures, such as vaccination.

Follow-Up Planning:

Arrange for follow-up care and give clear instructions for any necessary care after hospital discharge.

Ensure the patient and family understand the signs of potential complications and when to seek further medical attention.

Interprofessional Collaboration:

Work together with doctors, pharmacists, and other healthcare team members to ensure a well-coordinated and effective treatment approach.

Documentation Practices:

Maintain detailed and accurate records of assessments, nursing interventions, and patient responses to treatment.

Complications of Haemophilus Influenzae Infection

Meningitis-Related Complications:

Auditory Impairment: Hearing loss can occur in a significant percentage (15% to 30%) of meningitis survivors.

Neurological After-Effects: Neurological issues like cognitive deficits, motor skill problems, or seizures may persist.

Epiglottitis-Related Complications:

Airway Obstruction Emergency: Swelling of the epiglottis poses a critical risk of airway blockage.

Bacteremia-Related Complications:

Sepsis Development: Bacteremia can escalate to sepsis, a severe and widespread response to infection throughout the body.

Endocarditis Risk: Infection of the heart valves can occur, although it is less common.

Pneumonia-Related Complications:

Respiratory Failure: Severe pneumonia may lead to respiratory distress and the need for mechanical breathing support.

Arthritis-Related Complications:

Joint Deterioration: Infectious arthritis can cause damage to joints and impair their function.

Cellulitis-Related Complications:

Abscess Formation: Cellulitis can worsen and lead to the development of pus-filled abscesses in severe instances.

Osteomyelitis-Related Complications:

Bone Tissue Damage: Invasive infections can result in osteomyelitis, causing destruction of bone tissue.

Prevention of Haemophilus Influenzae Infection

Vaccination Strategies:

Hib Vaccine Importance: Vaccination against Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) is highly effective in preventing severe invasive diseases, including meningitis and bacteremia. It is a standard vaccine in childhood immunization schedules.

Pneumococcal Vaccine Role: Provides protection against pneumonia caused by various bacteria, including some Haemophilus influenzae strains.

Routine Immunization Adherence: Ensure timely administration of all routine childhood vaccines according to national guidelines.

Hygiene Best Practices:

Handwashing Diligence: Regular and thorough handwashing is crucial in preventing the spread of respiratory infections, including Haemophilus influenzae.

Environmental Precautions:

Avoidance of Crowded Settings: Limit exposure to crowded places, especially during seasons when respiratory infections are more prevalent.

Prompt Medical Intervention:

Early Treatment of Infections: Seek early diagnosis and treatment for respiratory infections to prevent complications and reduce bacterial spread.

Health Awareness and Education:

Public Education: Increase public awareness about the signs and symptoms of invasive infections and emphasize the importance of seeking prompt medical care.

Antibiotic Prophylaxis Considerations:

Selective Prophylaxis: In specific situations, antibiotic prophylaxis may be advised for close contacts of individuals with Haemophilus influenzae infection to prevent secondary cases.

Respiratory Hygiene Practices:

Cough Etiquette: Encourage the practice of covering the mouth and nose when coughing or sneezing to minimize the spread of respiratory droplets.

Healthy Lifestyle Maintenance:

Overall Wellness Promotion: Maintain good nutrition, engage in regular physical activity, and promote overall well-being to support a robust immune system.

We are a supportive platform dedicated to empowering student nurses and midwives through quality educational resources, career guidance, and a vibrant community. Join us to connect, learn, and grow in your healthcare journey

Quick Links

Our Courses

Legal / Policies

Get in Touch

(+256) 790 036 252

(+256) 748 324 644

Info@nursesonlinediscussion.com

Kampala ,Uganda

© 2025 Nurses online discussion. All Rights Reserved | Design & Developed by Opensigma