Pharmacology (I)

Subtopic:

Classifications of Drugs

A drug is defined as any substance that, when introduced into a living system, can alter its biological function or structure. This broad definition includes substances ranging from therapeutic medications to substances used for non-medical purposes. Drugs serve diverse roles, including:

Therapy: Used to treat or manage diseases and health conditions.

Prophylaxis: Employed to prevent the onset of illnesses, such as vaccines.

Diagnosis: Assist in identifying medical conditions, for example, contrast agents in imaging.

Symptomatic Relief: Used to reduce discomfort associated with various ailments, like pain relievers.

Drug Nomenclature: The Three Names of a Drug

Each medication is typically identified by three distinct types of names:

Chemical Name: This name provides a precise and detailed description of the drug’s chemical makeup. It is often complex and lengthy, making it impractical for routine clinical use. Example: (+/-)-2-(p-isobutylphenyl) propionic acid.

Generic Name (Nonproprietary Name): This is the officially recognized name assigned to a drug. It is simpler than the chemical name, universally acknowledged, and assigned by regulatory bodies like the FDA or EMA. Healthcare professionals commonly use generic names in prescriptions and dispensing. Example: ibuprofen.

Brand Name (Trade Name or Proprietary Name): This is the marketing name given by a pharmaceutical company under which the drug is sold. It’s a protected, trademarked name, often denoted with ®. Multiple companies may market the same generic drug under different brand names. Example: Brufen®, Advil®, Motrin® (all brand names for ibuprofen).

Examples of Generic and Brand Names:

It’s important to note that a single generic drug can be marketed under numerous brand names. Conversely, some brand names may represent combinations of active ingredients, or be a re-branded version of a generic drug.

| Generic Name | Brand Name(s) | Indication/Use |

| Amoxicillin | Amoxil®, Duramox®, Amoxapen®, etc. | Antibacterial (for bacterial infections) |

| Ibuprofen | Brufen®, Advil®, Motrin®, Nurofen®, etc. | Pain reliever, anti-inflammatory |

| Paracetamol | Panadol®, Tylenol®, Acetaminophen®, etc. | Pain reliever, fever reducer |

| Propranolol | Inderal®, InnoPran XL®, etc. | Antihypertensive, antianginal, anti-tremor |

| Salbutamol | Ventolin®, Proventil®, etc. | Bronchodilator (for asthma and lung conditions) |

| Diazepam | Valium®, Diastat®, etc. | Anti-anxiety, muscle relaxant |

| Metformin | Glucophage®, Fortamet®, etc. | Type 2 diabetes treatment |

| Lisinopril | Prinivil®, Zestril®, etc. | Antihypertensive |

| Atorvastatin | Lipitor®, etc. | Cholesterol-lowering agent |

Important Note: While generic and brand-name drugs share the same active ingredient, slight variations may exist in inactive components (like fillers or binders). These minor differences usually do not impact efficacy, but some individuals might notice subtle variations in their response. This is generally not clinically significant, but awareness is advisable.

Drug Classification

Drugs are systematically classified in several ways, each providing a unique perspective on their use, regulation, and pharmacological properties. The main classification systems include:

Prescription Classification

Pharmacological Classification

Legal Classification

1. Prescription Classification

This system categorizes drugs based on their availability—whether a prescription is needed or if they can be purchased without one (over-the-counter). Prescription drugs typically require medical supervision due to their potency, potential for serious side effects, or risk of misuse.

Prescription-Only Medicines (POM): These medications mandate a prescription from a licensed healthcare provider due to the risks associated with misuse or unsupervised use. Examples:

Antibiotics: Amoxicillin, Ciprofloxacin, and others. Antibiotic choice is tailored to the specific bacteria and its susceptibility.

Analgesics: Diclofenac (NSAID). Other NSAIDs like ibuprofen and naproxen also require prescriptions in certain strengths or formulations.

Cardiovascular Medications: Nifedipine (calcium channel blocker). A wide array of cardiovascular drugs exist, each with specific actions on heart function, blood pressure, etc.

Antidepressants: Sertraline (Zoloft), Fluoxetine (Prozac). Require medical supervision for safe and effective use.

Anti-anxiety Medications: Alprazolam (Xanax), Diazepam (Valium). Potential for dependence necessitates prescription control.

Asthma Inhalers: Many inhalers, especially those with corticosteroids or bronchodilators, are prescription-only.

Diabetes Medications: Insulin, Metformin. Require careful medical management to ensure blood sugar control.

Over-the-Counter (OTC) Drugs: These medications are considered safe for self-use when label instructions are followed. They are available without prescription in pharmacies and retail stores. Examples:

Analgesics: Panadol® (paracetamol/acetaminophen), Hedex®. Formulations vary, affecting efficacy and side effects.

Vitamins and Minerals: Wide range available, but efficacy and safety depend on individual needs and dosage.

Cough and Cold Remedies: Goodmorning syrup®. Active ingredients and potential interactions should be considered.

Antacids: Tums, Rolaids. For heartburn relief; overuse can be problematic.

Antihistamines: Diphenhydramine (Benadryl), Cetirizine (Zyrtec). For allergy relief; some cause drowsiness.

Laxatives: Various types for constipation; overuse can lead to dependence.

2. Pharmacological Classification

This system groups drugs based on their mechanism of action or physiological effect. It emphasizes what the drug does within the body.

By Target Body System: Drugs are categorized by the organ system they primarily influence.

Cardiovascular Drugs: Affecting the heart and blood vessels (e.g., beta-blockers, ACE inhibitors, diuretics).

Neurological Drugs: Affecting the nervous system (e.g., antidepressants, antipsychotics, anticonvulsants).

Gastrointestinal Drugs: Affecting the digestive system (e.g., antacids, laxatives).

Respiratory Drugs: Affecting the lungs and airways (e.g., bronchodilators, corticosteroids).

By Activity on Microorganisms: Crucial for antimicrobial drugs.

Antibiotics: Target bacteria (e.g., penicillin, tetracycline, cephalosporins).

Antivirals: Target viruses (e.g., acyclovir, oseltamivir).

Antifungals: Target fungi (e.g., fluconazole, ketoconazole).

3. Legal Classification

Legal classification categorizes drugs based on their potential for misuse and accepted medical applications. This system considers therapeutic use, abuse potential, and legal status.

Class A Drugs: Substances under strict control.

Examples: Morphine, Pethidine, Cocaine.

Class B Drugs: A broader category of controlled substances.

Examples: Phenobarbitone, Ciprofloxacin, Amoxicillin, Diazepam, Codeine, Griseofulvin, Metformin.

Class C Drugs: Typically OTC drugs considered safe for general public use without prescription.

Examples: Paracetamol, Aspirin.

| Class | Description | Examples |

| Class A | High abuse potential, strictly controlled substances | Morphine, Pethidine |

| Class B | Prescription required, lower abuse potential | Amoxicillin, Antihypertensives |

| Class C | Over-the-counter, safe for self-medication | Paracetamol, Aspirin |

Schedule of Controlled Substances

Controlled substances are further classified into schedules based on their abuse potential and accepted medical utility. This classification is primarily determined by abuse potential and medical usefulness.

Schedule I Drugs (High Abuse Potential, No Accepted Medical Use): Subject to the most stringent controls.

Examples: Heroin, Lysergide (LSD).

Characteristics: High abuse potential and no currently recognized medical use.

Schedule II Drugs (High Abuse Potential, Accepted Medical Use): Tightly regulated with specific prescribing protocols.

Examples: Morphine, Codeine, Pethidine, Methadone, Cocaine.

Characteristics: High abuse potential but with accepted medical applications. Can lead to severe dependence.

Schedule III Drugs (Moderate Abuse Potential, Accepted Medical Use): Less stringent controls than Schedules I & II, but still require monitoring.

Examples: Phenobarbitone, preparations with limited opioid quantities (e.g., codeine/paracetamol combinations).

Characteristics: Lower abuse potential than Schedules I & II, with accepted medical uses.

Schedule IV Drugs (Low Abuse Potential, Accepted Medical Use): Lower abuse potential, but dependence possible with prolonged use.

Examples: Diazepam, Lorazepam.

Characteristics: Lower abuse potential than Schedules I-III, with accepted medical uses.

Schedule V Drugs (Lowest Abuse Potential, Accepted Medical Use): Often available with less strict regulatory oversight.

Examples: Cough/diarrhea drugs with limited opioids like Loperamide or codeine-containing syrups.

Characteristics: Lowest abuse potential due to low strength, with accepted medical uses.

Drug Administration Routes

Drug administration refers to the methods used to deliver drugs into the body.

| Route | Description | Advantages | Disadvantages |

| Enteral (Oral) | Taken by mouth | Convenient, safe | Slow onset, variable GI absorption |

| Parenteral | Injections (IV, IM, SC) directly into body | Rapid effect, precise control | Requires skill, painful, infection risk |

| Topical | Applied to skin or mucous membranes | Localized effect, non-invasive | Slow absorption, limited drug types |

| Inhalational | Inhaled gases or aerosols | Quick relief for respiratory conditions | Requires technique, potential for irritation |

Prescription Writing and Dispensing

Prescription Writing

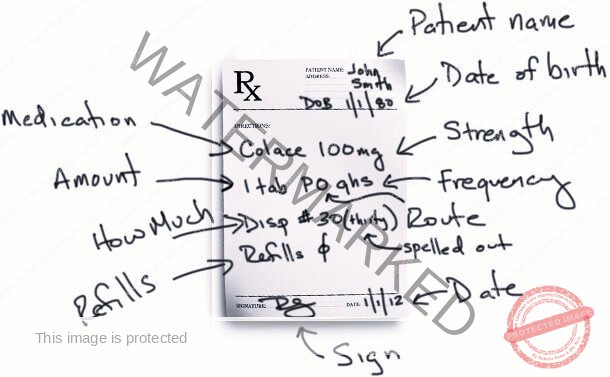

A prescription is defined as a formal written directive issued by a qualified healthcare professional (such as a physician, nurse practitioner, or physician associate) to a pharmacist or another authorized dispenser. This document legally instructs them to provide a specified medication to a named patient. The individual issuing the prescription holds both a legal and moral obligation to ensure the prescription is accurate, unambiguous, and safe for the patient.

A well-composed prescription must contain the following crucial elements:

Legibility: Must be written clearly and readably using indelible ink (permanent ink that resists fading or smudging).

Date: The exact date on which the prescription was written.

Patient Identification:

The patient’s complete name and residential address.

For pediatric patients, age and body weight are essential for precise dosage calculation.

Diagnosis (Medical Indication): The clinical reason for prescribing the medication. While not always explicitly written on every prescription, it is fundamentally important for validating the treatment and assessing the drug’s suitability for the condition.

Medication Specifications:

Drug Name: The full medication name (using the generic name is preferred for clarity and to avoid brand confusion).

Dosage Form: The physical form of the medication (e.g., tablets, capsules, solution for injection).

Strength: The quantity of active ingredient in each dose unit (e.g., 500 mg, 100 IU).

Quantity to Dispense: The total amount of medication to be provided to the patient.

Treatment Duration: The length of time the medication should be taken (e.g., “for 5 days“, “until finished“).

Frequency of Administration: How often the medication should be taken (e.g., “once daily“, “every 8 hours“).

Directions for Use (Patient Instructions): Clear and simple directions on how to take the medication, including any specific timing instructions (e.g., “take with food“, “at bedtime only“).

Prescriber Identification: The complete name, professional address, and contact information (including a phone number) of the prescribing healthcare professional.

Healthcare Facility Details: The name and address of the healthcare facility where the prescription was issued.

Qualities of an Effective Prescriber

An effective prescriber demonstrates knowledge, diligence, and patient-centered care. They:

Prescribe Judiciously: Only recommend medication when truly necessary, avoiding unnecessary drug use.

Select Appropriate Treatments: Choose the most effective and safest treatment option based on the patient’s specific medical condition, considering factors like allergies and concurrent medications.

Adapt Treatment Plans: Monitor the patient’s response to the prescribed treatment and adjust the dosage or change the medication as needed to optimize outcomes.

Communicate Clearly with Patients: Effectively explain the patient’s condition, the medication’s purpose, potential adverse effects, and precise instructions for proper administration.

Follow Up Patient Progress: Schedule follow-up appointments to assess treatment effectiveness and make any necessary modifications to the care plan.

The Process of Rational Prescribing

Effective prescribing follows a structured, logical approach:

Define the Patient Problem: Accurately diagnose the patient’s medical condition through thorough assessment.

Establish Therapeutic Goals: Clearly define the desired outcome of the treatment (e.g., symptom control, disease eradication, improvement in function).

Choose the Optimal Treatment: Select the most suitable medication that is effective, safe, and well-tolerated for the individual patient, considering their overall health status, potential for drug interactions, and medication costs.

Generate a Precise Prescription: Write a complete and accurate prescription adhering to all established guidelines for clarity and safety.

Educate the Patient Thoroughly: Inform the patient about their medical condition, the prescribed treatment regimen, and potential side effects to expect and manage.

Review and Modify Treatment Regularly: Continuously monitor the patient’s response to therapy and be prepared to adjust the treatment plan based on their progress and any emerging issues.

Over-Prescribing vs. Under-Prescribing: Two Sides of the Same Coin

Both excessive and insufficient prescribing practices create significant problems:

Over-Prescribing:

Wastes healthcare resources due to unnecessary medication use.

Increases the risk of drug-related side effects and adverse reactions.

Can contribute to medication dependence and addiction.

Escalates overall healthcare expenses.

Under-Prescribing:

Results in ineffective treatment of the patient’s condition.

May lead to worsening of the illness or delayed recovery.

Can ultimately increase long-term treatment costs as more intensive interventions may be needed later.

The Dispensing Process

Dispensing is the process of preparing and providing the prescribed medication to the patient according to the instructions on the prescription. This critical step is performed by a licensed pharmacist or other authorized personnel, like a trained nurse or pharmacy technician.

Key Roles of a Dispenser

Accurate Medication Dispensing: Filling prescriptions precisely as written, ensuring the correct drug, dosage form, and strength are provided.

Comprehensive Patient Education: Providing patients with essential information about their medications, including usage instructions, potential side effects, and storage guidelines.

Meticulous Record Keeping: Maintaining accurate and up-to-date records of all dispensed medications for inventory management and patient safety.

Optimal Drug Storage: Ensuring medications are stored under appropriate conditions to maintain their quality and efficacy (e.g., temperature, light protection).

Prescriber Consultation (as needed): Advising prescribers on medication-related issues such as potential drug interactions, dosage adjustments, or alternative therapies (this role may vary based on setting).

Drug Procurement Assistance (in some contexts): Assisting with the ordering and stocking of medications to maintain adequate pharmacy inventory (role varies by setting).

Standard Dispensing Procedure

Prescription Receipt and Verification: Receiving the prescription and initially checking it for completeness, legibility, and accuracy of all required elements.

Prescription Interpretation: Clearly understanding all instructions written on the prescription, including drug name, dosage, route, and frequency.

Medication Retrieval: Obtaining the correct medication product from pharmacy stock, verifying the drug name, strength, and expiry date.

Patient Counseling and Information: Providing clear and understandable explanations to the patient on how to take the medication, when to take it, potential side effects, and any necessary precautions.

Medication Packaging and Labeling: Ensuring the medication is dispensed in appropriate packaging and accurately labeled with patient information, drug name, dosage instructions, and any required warnings.

Dispensing Record Documentation: Documenting the entire dispensing process in pharmacy records, including date dispensed, drug details, quantity, and patient information.

Medication Handover to Patient: Providing the prepared medication to the patient or their authorized representative, confirming patient identity and answering any final questions.

Essential Knowledge for Dispensing Professionals

Dispensers require a broad and deep knowledge base, including:

Detailed knowledge of drug formulations and appropriate dosages.

Understanding of medication indications (approved uses) and therapeutic applications.

Awareness of precautions and contraindications for different medications.

Knowledge of potential side effects and adverse drug reactions.

Expertise in proper packaging, labeling requirements, and storage conditions for various drug products.

Familiarity with legal requirements and regulations for dispensing controlled substances and prescription medications.

Understanding of medication administration techniques for different dosage forms and routes of administration.

Basic understanding of common disease processes and how medications are used to treat them.

Prescribing Medications: Key Considerations

Prescribing effectively involves careful selection of the appropriate drug, dosage, route of administration, and duration of treatment, tailored to the individual patient.

| Consideration | Details |

| Patient Factors | Age, weight, sex, pregnancy status, kidney and liver function, known allergies, co-existing medical conditions (comorbidities). |

| Drug Factors | Efficacy (how well it works), safety profile, potential side effects, likelihood of drug interactions, medication cost to the patient. |

| Compliance | Ensuring the patient understands the treatment regimen and is likely to adhere to it for optimal therapeutic benefit. |

Essential Elements of a Legal Prescription

A legally valid prescription must contain specific categories of information:

| Prescription Element | Description |

| Patient Information | Full name of the patient, and in some cases, age and address. |

| Drug Details | Medication name, strength, prescribed dosage, total quantity to be dispensed, and specific administration instructions. |

| Prescriber Information | Prescriber’s name, professional signature, and relevant professional registration number. |

Common Abbreviations in Drug Administration

Healthcare professionals frequently use abbreviations in prescriptions to conserve space and time. These abbreviations are generally categorized by their relation to administration frequency or dosage form.

Abbreviations Related to Frequency of Drug Administration

| Abbreviation | Meaning |

| OD | Once daily |

| BID | Twice daily |

| TDS | Three times daily |

| QID | Four times daily |

| PRN | When necessary |

| Stat | Immediately |

| Ac | Before meals |

| Pc | After meals |

Abbreviations Related to Dosage Form

| Abbreviation | Meaning |

| Caps | Capsules |

| Tabs | Tablets |

| Syr | Syrup |

| Gut | Eye drops |

| Inf. | Infusion |

| Pess. | Pessaries |

| Mist | Mixture |

| Iv | Intravenous |

Get in Touch

(+256) 790 036 252

(+256) 748 324 644

Info@nursesonlinediscussion.com

Kampala ,Uganda

© 2025 Nurses online discussion. All Rights Reserved Design & Developed by Opensigma.co