Special Investigations in Surgical Nursing

Subtopic:

Anthrax

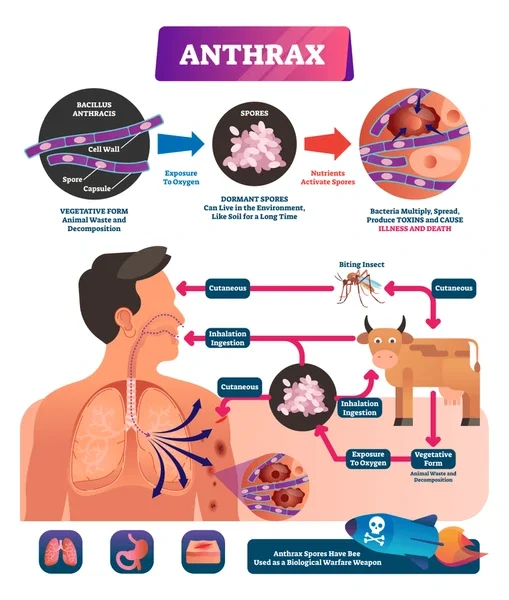

Anthrax is a severe infectious illness triggered by the bacterium Bacillus anthracis. Classified as a zoonotic disease, it signifies its capacity to transmit from animals to humans. Though infrequent in humans, anthrax remains a notable public health concern, particularly due to its potential weaponization as a bioweapon.

Etiology

Bacillus anthracis is a gram-positive, rod-shaped bacterium distinguished by its formation of highly resilient spores. These spores exhibit remarkable longevity, capable of persisting in soil and on animal-derived products for extended durations, even spanning decades. Under conducive conditions, such as entry into a living organism, these spores germinate into active bacteria. These vegetative bacteria then elaborate toxins that are central to the disease’s development. Key toxins produced include edema toxin, lethal toxin, and protective antigen. These toxins disrupt essential cellular functions, ultimately giving rise to the characteristic symptoms associated with anthrax.

Forms of Transmission and Routes of Transmission (Types of Anthrax)

Anthrax manifests in three primary forms, each distinguished by its specific mode of transmission:

Cutaneous Anthrax: Recognized as the most prevalent form in humans, cutaneous anthrax arises when spores gain entry into the body through skin abrasions or cuts. This often occurs via direct contact with infected animals or contaminated animal byproducts (e.g., hides, wool, and hair). Spore germination at the skin entry site leads to the development of a distinctive skin lesion.

Inhalation Anthrax: Identified as the most perilous form, inhalation anthrax results from the inhalation of anthrax spores into the lungs. Initially, it may present with influenza-like symptoms, but it rapidly escalates to severe respiratory distress and potentially fatal septicemia. While less common than cutaneous anthrax, inhalation anthrax is associated with the highest fatality rate.

Gastrointestinal Anthrax: Considered the least frequent form, gastrointestinal anthrax occurs following the ingestion of spores, typically through the consumption of contaminated meat. Symptoms encompass nausea, vomiting, abdominal discomfort, and bloody diarrhea. Similar to inhalation anthrax, the gastrointestinal form carries a significant mortality risk if left untreated.

Incubation Period

The duration of the incubation period varies depending on the specific form of anthrax and the route of infection:

Cutaneous Anthrax: Typically 1-7 days, commonly 2-5 days.

Inhalation Anthrax: Ranges from 1-60 days, generally 1-7 days.

Gastrointestinal Anthrax: Usually 1-7 days, often 1-5 days.

Clinical Features

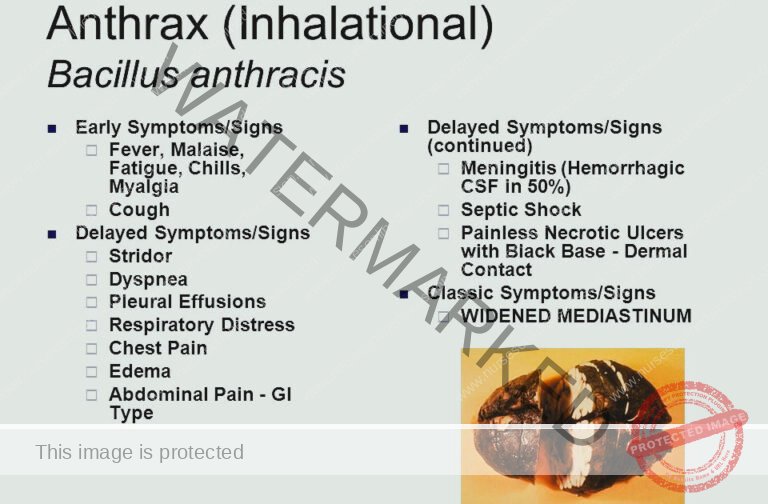

The way anthrax presents itself can differ significantly depending on the specific type of infection:

Cutaneous Anthrax: Starts as a seemingly harmless, itchy bump resembling an insect bite, which is painless. Within a couple of days, this evolves into a blister (vesicle) and subsequently a painless ulcer, typically 1-3 cm in diameter. A defining feature is the black, dead tissue (eschar) in the centre, resembling a scab. Swollen lymph nodes (lymphadenopathy), swelling (edema), and fever might also be present.

Inhalation Anthrax: Initially, symptoms are similar to the flu, including fever, cough, tiredness, and muscle pain. As it progresses, more serious signs emerge, such as shortness of breath, chest discomfort, difficulty breathing, shock, and a condition affecting blood clotting known as disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC).

Gastrointestinal Anthrax: Characterized by intense abdominal pain, feeling sick to the stomach, throwing up, bloody diarrhoea, and potentially life-threatening blood infection (sepsis).

Definitive Diagnosis and Investigations

Confirmation of diagnosis is based on combining clinical signs, information about potential exposure, and laboratory testing:

Clinical Examination: A thorough evaluation of the patient’s symptoms and medical background is essential.

Microscopic Examination: Using Gram staining on samples like blood or wound fluid can reveal the presence of Gram-positive rod-shaped bacteria, which are characteristic of anthrax.

Culture: Growing and identifying B. anthracis bacteria from samples provides a definitive diagnosis. This requires a high level of safety precautions in the lab.

Serological Tests: Detecting antibodies against anthrax toxins in the blood can be supportive but isn’t always conclusive on its own.

PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction): This technique can detect the genetic material (DNA) of B. anthracis in patient samples.

Management

Goals of Treatment:

To get rid of the anthrax infection.

To counteract the harmful substances (toxins) produced by the bacteria.

To provide supportive care to handle any complications that arise.

Medical Treatment:

The primary approach to treating anthrax is through antibiotic medications:

First-line Antibiotics: Ciprofloxacin (or other fluoroquinolone antibiotics) or doxycycline are typically used first.

Alternative Antibiotics: For patients with allergies to fluoroquinolones, other options include penicillin, clindamycin, or vancomycin.

Treatment Duration: Antibiotics are usually given for a total of 60 days.

Specific Anthrax Types:

Cutaneous: The vast majority (95%) of anthrax infections occur through skin contact, often via cuts or scrapes. It starts as an itchy raised spot like a bug bite. In a day or two, it becomes a blister and then a painless ulcer, usually 1-3 cm, with a central black necrotic area (eschar). Nearby lymph nodes may swell. Without treatment, cutaneous anthrax leads to death in about 20% of cases. First-line antibiotic is ciprofloxacin 500 mg every 12 hours. Alternatives are doxycycline 100 mg every 12 hours or amoxicillin 1 g every 8 hours.

Inhalation: Initial symptoms might resemble a common cold. After a few days, breathing difficulties and shock can develop. Inhalation anthrax is often fatal. Besides antibiotics, supportive care such as oxygen, mechanical ventilation, fluids, and shock management may be needed. Raxibacumab (a monoclonal antibody targeting protective antigen) might be used in severe cases.

Gastrointestinal: Characterized by severe inflammation of the digestive tract. Initial signs include nausea, loss of appetite, vomiting, and fever, followed by abdominal pain, vomiting blood, and severe diarrhoea. Intestinal anthrax is fatal in 25% to 60% of cases.

Nursing Care

Nursing care is centred around:

Vital Signs Monitoring: Closely tracking breathing, blood pressure, heart rate, and body temperature.

Respiratory Support: Providing oxygen and assisting with breathing machines (mechanical ventilation) if needed.

Fluid and Electrolyte Balance: Maintaining proper hydration and monitoring salt and mineral levels in the body.

Wound Care: For skin anthrax, providing appropriate care to the wound area to aid healing.

Infection Control: Strictly following infection control measures to prevent spread.

Psychological Support: Offering emotional support to the patient and their family during this stressful time.

Management Until Discharge

Continue the prescribed antibiotic course.

Monitor for any signs of the infection returning or new problems arising.

Educate the patient about their medication, wound care (if needed), and schedule for follow-up appointments.

Discharge Advice

Finish the entire course of prescribed antibiotics.

Watch for any symptoms coming back.

Report any new or concerning symptoms to their healthcare provider.

Attend all scheduled follow-up appointments.

Prevention

Animal-Focused Prevention:

Safe Disposal of Carcasses: Properly burying dead animal bodies, hides, and skins is crucial. Burning is not effective as it can release spores into the air, increasing spread risk.

Avoid Handling: Do not skin or handle dead animals if anthrax is suspected, as this allows spore formation, which can persist in soil for many years. Meat from these animals should never be eaten.

Movement Control: Restrict the movement of animals and animal products (like hides or wool) from infected areas to non-infected areas to stop the disease from spreading.

Mass Animal Vaccination: Implement widespread vaccination programs for livestock in regions known for anthrax outbreaks.

Human-Focused Prevention:

Vaccination: Anthrax vaccine for humans is recommended for those at high risk of exposure, including:

Lab workers directly handling Bacillus anthracis.

People who work with potentially contaminated animal products (e.g., hides, wool).

Individuals living in or travelling to areas where anthrax is common.

Health Education: Public awareness campaigns to educate communities about how anthrax spreads, prevention methods, and early symptom recognition. This includes safe handling of animal products and seeking prompt medical attention if exposure is suspected.

Complications

Sepsis: A dangerous, life-threatening condition where the body has an extreme reaction to an infection.

Respiratory Failure: A common serious complication of inhalation anthrax.

Meningitis: Inflammation of the protective membranes surrounding the brain and spinal cord.

Shock: A critical drop in blood pressure that can be life-threatening.

DIC (Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation): A condition affecting blood clotting.

Death: Untreated inhalation and gastrointestinal anthrax have a high risk of death.

We are a supportive platform dedicated to empowering student nurses and midwives through quality educational resources, career guidance, and a vibrant community. Join us to connect, learn, and grow in your healthcare journey

Quick Links

Our Courses

Legal / Policies

Get in Touch

(+256) 790 036 252

(+256) 748 324 644

Info@nursesonlinediscussion.com

Kampala ,Uganda

© 2025 Nurses online discussion. All Rights Reserved | Design & Developed by Opensigma