circulatory system

Subtopic:

Congestive Cardiac Failure

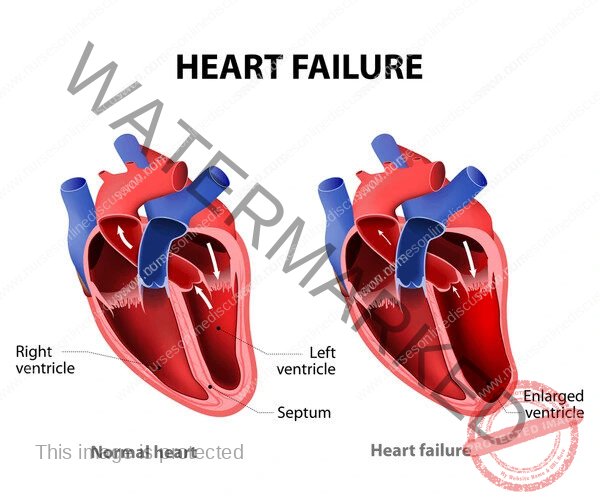

Congestive Heart Failure (CHF), often simply referred to as Heart Failure (HF), is a complex clinical syndrome that results from any structural or functional impairment of ventricular filling or ejection of blood.

It is characterized by the inability of the heart to pump sufficient blood to meet the metabolic demands of the body, or the ability to do so only at elevated filling pressures.

CHF is a progressive condition that leads to significant morbidity and mortality. It is not a single disease but rather the end-stage manifestation of various cardiovascular diseases.

The term “congestive” specifically refers to the accumulation of fluid in the lungs, abdomen, and peripheral tissues due to the heart’s inability to effectively circulate blood. While not all patients with heart failure exhibit overt congestion, it is a common and often prominent feature, particularly in advanced stages.

2. Epidemiology

CHF is a major public health concern globally, with increasing prevalence due to aging populations and improved survival rates from conditions like myocardial infarction.

Prevalence: Affects millions worldwide. In developed countries, the prevalence is estimated to be around 1-2% of the adult population, rising significantly with age, affecting over 10% of individuals aged 70 and older.

Incidence: The incidence is also substantial, with hundreds of thousands of new cases diagnosed annually.

Mortality: CHF is associated with a high mortality rate. The 5-year survival rate after diagnosis is approximately 50%, which is comparable to or worse than many common cancers.

Hospitalizations: It is a leading cause of hospitalization in individuals over 65 years of age, placing a significant burden on healthcare systems.

Sex Differences: While overall prevalence is similar, there can be differences in etiology and phenotype. For instance, HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) is more common in women.

3. Pathophysiology

The core issue in CHF is the inability of the heart to maintain adequate cardiac output relative to metabolic needs. This can result from impaired contractility, increased afterload, impaired relaxation, or filling abnormalities. The body activates several compensatory mechanisms in response to reduced cardiac output, which are initially beneficial but become detrimental over time, contributing to the progression of the disease.

Key compensatory mechanisms include:

Activation of the Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System (RAAS): Reduced renal perfusion leads to renin release, activating the RAAS. This results in angiotensin II production (vasoconstriction, aldosterone release) and aldosterone release (sodium and water retention). This increases blood volume and blood pressure, initially helping to maintain cardiac output but increasing cardiac workload and contributing to congestion.

Activation of the Sympathetic Nervous System: Reduced cardiac output stimulates baroreceptors, leading to increased sympathetic outflow. This results in increased heart rate, contractility, and vasoconstriction. While initially supporting cardiac output, chronic sympathetic activation increases myocardial oxygen demand, can cause arrhythmias, and contributes to cardiac remodeling.

Myocardial Hypertrophy and Remodeling: Chronic pressure or volume overload leads to structural changes in the heart muscle. This can involve concentric hypertrophy (thickening of the ventricular wall in response to pressure overload) or eccentric hypertrophy (dilation of the ventricular chamber in response to volume overload). While initially adaptive, prolonged remodeling can lead to fibrosis, impaired contractility, and chamber dilation, further worsening cardiac function.

Release of Natriuretic Peptides (BNP and ANP): In response to increased atrial and ventricular stretch, the heart releases atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) and brain natriuretic peptide (BNP). These peptides promote vasodilation, natriuresis, and diuresis, counteracting the effects of the RAAS and sympathetic nervous system. They are important biomarkers for diagnosing and monitoring CHF.

CHF is broadly classified into two main types based on left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF):

Heart Failure with Reduced Ejection Fraction (HFrEF): Also known as systolic heart failure, characterized by a reduced LVEF (typically < 40%). The primary problem is impaired ventricular contractility, leading to difficulty ejecting blood. Common causes include myocardial infarction, dilated cardiomyopathy, and chronic volume overload.

Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction (HFpEF): Also known as diastolic heart failure, characterized by a preserved LVEF (typically ≥ 50%). The primary problem is impaired ventricular relaxation and increased stiffness, leading to difficulty filling with blood during diastole. Common causes include hypertension, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, restrictive cardiomyopathy, and aging. A subset of patients may have Heart Failure with Mid-Range Ejection Fraction (HFmrEF) with LVEF between 40% and 49%.

4. Etiology (Causes and Risk Factors)

Numerous conditions can lead to CHF. The most common causes and risk factors include:

Coronary Artery Disease (CAD) and Myocardial Infarction (MI): The most common cause of HFrEF. Ischemia and necrosis of myocardial tissue impair contractility and can lead to remodeling.

Hypertension: A major risk factor for both HFrEF and HFpEF. Chronic pressure overload leads to left ventricular hypertrophy and diastolic dysfunction.

Valvular Heart Disease: Stenosis or regurgitation of heart valves can cause pressure or volume overload on the ventricles, leading to hypertrophy, dilation, and impaired function.

Cardiomyopathies: Diseases of the heart muscle itself, including dilated cardiomyopathy (most common cause of HFrEF), hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (common cause of HFpEF), restrictive cardiomyopathy, and arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia.

Diabetes Mellitus: Contributes to macrovascular and microvascular disease, increasing the risk of CAD and hypertension. Diabetic cardiomyopathy is also a distinct entity.

Arrhythmias: Chronic rapid heart rates (e.g., atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response) can lead to tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy. Slow heart rates or conduction blocks can also impair cardiac output.

Congenital Heart Disease: Structural abnormalities present at birth can lead to chronic pressure or volume overload.

Thyroid Disorders: Both hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism can affect cardiac function.

Infections: Viral myocarditis can cause acute or chronic heart failure.

Toxins: Alcohol, certain chemotherapeutic agents (e.g., doxorubicin), and recreational drugs can be cardiotoxic.

Pulmonary Hypertension: Increased pressure in the pulmonary arteries increases the workload on the right ventricle, potentially leading to right-sided heart failure.

Obesity: Associated with increased risk of hypertension, diabetes, and sleep apnea, all of which contribute to CHF risk.

Sleep Apnea: Can lead to intermittent hypoxia, increased sympathetic tone, and pulmonary hypertension.

5. Clinical Manifestations (Signs and Symptoms)

The signs and symptoms of CHF result from reduced cardiac output and/or elevated filling pressures leading to congestion. The severity of symptoms often correlates with the stage of the disease.

Symptoms:

Dyspnea: Shortness of breath, initially on exertion, progressing to dyspnea at rest. Orthopnea (dyspnea when lying flat, relieved by sitting up) and paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea (PND – sudden onset of severe dyspnea at night that awakens the patient) are characteristic of left-sided heart failure and pulmonary congestion.

Fatigue and Weakness: Due to reduced blood flow to skeletal muscles.

Peripheral Edema: Swelling in the ankles, feet, and legs, often bilateral and pitting, due to fluid retention and increased hydrostatic pressure.

Abdominal Swelling/Ascites: Fluid accumulation in the abdominal cavity, indicating right-sided heart failure and venous congestion.

Weight Gain: Due to fluid retention.

Nausea and Anorexia: Can occur due to congestion of the gastrointestinal tract and reduced blood flow.

Cough: Often dry and hacking, especially when lying down, due to pulmonary congestion.

Palpitations: Awareness of heartbeats, which can be due to underlying arrhythmias or increased heart rate.

Mental Status Changes: Confusion or impaired concentration in severe cases due to reduced cerebral perfusion.

Signs (on Physical Examination):

Tachycardia: Increased heart rate.

Tachypnea: Increased respiratory rate.

Jugular Venous Distension (JVD): Visible bulging of the jugular veins in the neck, indicating elevated right atrial pressure.

Pulmonary Rales (Crackles): Abnormal lung sounds heard on auscultation, indicating fluid in the alveoli.

Pleural Effusion: Accumulation of fluid in the pleural space, causing decreased breath sounds and dullness to percussion.

Peripheral Edema: Visible swelling, often pitting, in dependent areas.

Hepatomegaly: Enlarged liver due to venous congestion.

Hepatojugular Reflux: Increase in JVD when pressure is applied to the abdomen, indicating elevated right atrial pressure.

Ascites: Presence of fluid in the abdominal cavity, detected by shifting dullness on percussion.

Cool Extremities: Due to reduced peripheral perfusion.

S3 Gallop: An abnormal heart sound heard during diastole, indicating rapid ventricular filling into a dilated and poorly compliant ventricle.

Murmurs: May be present due to underlying valvular heart disease.

6. Diagnosis

The diagnosis of CHF is based on a combination of clinical history, physical examination, and diagnostic tests.

History and Physical Examination: Detailed assessment of symptoms, risk factors, and physical signs as described above.

Electrocardiogram (ECG): Can reveal evidence of underlying causes (e.g., previous MI, arrhythmias, ventricular hypertrophy) but is not diagnostic of CHF itself. A normal ECG makes a diagnosis of systolic heart failure less likely.

Chest X-ray: Can show cardiomegaly (enlarged heart), pulmonary vascular congestion, interstitial edema, alveolar edema, and pleural effusions.

Echocardiography: The most important diagnostic test. It provides information on left ventricular size and function (LVEF), wall motion abnormalities, valvular function, chamber pressures, and estimates of filling pressures. This is crucial for distinguishing between HFrEF and HFpEF.

Natriuretic Peptides (BNP or NT-proBNP): Elevated levels of BNP or NT-proBNP (N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide) are strong indicators of heart failure and can be used to support the diagnosis, assess severity, and monitor treatment response. These peptides are released in response to increased ventricular stretch.

Blood Tests: Routine blood tests include complete blood count (to rule out anemia), electrolytes (to assess renal function and look for abnormalities related to diuretics), renal function tests (creatinine, urea), liver function tests, and thyroid function tests (to rule out thyroid-related causes).

Cardiac Catheterization: May be performed to assess for coronary artery disease (if suspected as the cause) or to measure intracardiac pressures directly.

Stress Testing: Can be used to evaluate for inducible ischemia as a cause of heart failure.

Cardiac MRI: Provides detailed images of the heart and can be useful in specific cases, such as evaluating for infiltrative cardiomyopathies.

7. Classification and Staging

CHF is classified to assess its severity and guide management. Two commonly used systems are:

New York Heart Association (NYHA) Functional Classification: Based on the degree of limitation of physical activity due to symptoms.

Class I: No limitation of physical activity. Ordinary physical activity does not cause undue fatigue, palpitation, or dyspnea.

Class II: Slight limitation of physical activity. Comfortable at rest. Ordinary physical activity results in fatigue, palpitation, or dyspnea.

Class III: Marked limitation of physical activity. Comfortable at rest. Less than ordinary activity causes fatigue, palpitation, or dyspnea.

Class IV: Unable to carry on any physical activity without discomfort. Symptoms of heart failure at rest. If any physical activity is undertaken, discomfort is increased.

American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) Stages of Heart Failure: Describes the progression of the disease, starting from risk factors to advanced disease. This staging is useful for identifying patients at risk and implementing preventative strategies.

Stage A: At high risk for heart failure but without structural heart disease or symptoms of heart failure (e.g., patients with hypertension, diabetes, CAD, obesity, metabolic syndrome).

Stage B: Structural heart disease present but without signs or symptoms of heart failure (e.g., patients with previous MI, LV hypertrophy, valvular heart disease, but no current symptoms).

Stage C: Structural heart disease with prior or current symptoms of heart failure.

Stage D: Refractory heart failure requiring specialized interventions.

8. Management

The management of CHF is multifaceted and aims to improve symptoms, enhance quality of life, reduce hospitalizations, and prolong survival. Treatment strategies vary depending on the underlying cause, type of heart failure (HFrEF vs. HFpEF), and severity.

Non-Pharmacological Management:

Lifestyle Modifications:

Sodium Restriction: Limiting sodium intake (typically < 1500 mg/day) helps reduce fluid retention and congestion.

Fluid Restriction: May be necessary in patients with advanced CHF and hyponatremia to manage fluid overload.

Regular Exercise: Medically supervised exercise programs (cardiac rehabilitation) are beneficial in stable patients to improve exercise tolerance and quality of life.

Weight Management: Achieving and maintaining a healthy weight is important.

Smoking Cessation: Smoking significantly worsens cardiovascular health.

Alcohol Restriction: Excessive alcohol intake can be cardiotoxic.

Patient Education and Self-Care: Educating patients about their condition, medications, symptom monitoring (e.g., daily weight checks), and when to seek medical attention is crucial for self-management and preventing exacerbations.

Pharmacological Management (Primarily for HFrEF, with some overlap for HFpEF):

Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitors (ACEIs) or Angiotensin II Receptor Blockers (ARBs): Cornerstone of HFrEF treatment. They block the RAAS, reducing vasoconstriction, aldosterone release, and cardiac remodeling. Examples: enalapril, lisinopril, losartan, valsartan.

Angiotensin Receptor-Neprilysin Inhibitors (ARNIs): A combination of an ARB (valsartan) and a neprilysin inhibitor (sacubitril). Neprilysin inhibition increases levels of natriuretic peptides and other vasoactive peptides, leading to vasodilation and natriuresis. ARNIs have shown superior mortality benefit compared to ACEIs in appropriate HFrEF patients. Example: sacubitril/valsartan.

Beta-Blockers: Block the effects of the sympathetic nervous system, reducing heart rate, contractility, and myocardial oxygen demand. They also have anti-remodeling effects. Examples: carvedilol, metoprolol succinate, bisoprolol. Should be initiated at low doses and titrated slowly in stable patients.

Mineralocorticoid Receptor Antagonists (MRAs): Block the effects of aldosterone, reducing sodium and water retention, potassium excretion, and myocardial fibrosis. Examples: spironolactone, eplerenone. Beneficial in patients with symptomatic HFrEF and reduced LVEF.

Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) Inhibitors: Originally developed for diabetes, these agents have shown significant benefits in reducing cardiovascular death and hospitalizations for heart failure in patients with and without diabetes. Examples: dapagliflozin, empagliflozin.

Diuretics: Used to relieve symptoms of congestion (dyspnea, edema). They promote excretion of sodium and water. Loop diuretics (e.g., furosemide, bumetanide, torsemide) are most commonly used for their potency. Thiazide diuretics (e.g., hydrochlorothiazide) may be added for synergistic effect in resistant cases. Diuretics do not improve survival but are essential for symptom management.

Digoxin: A cardiac glycoside that increases myocardial contractility and slows heart rate. It can help reduce symptoms and hospitalizations in HFrEF but does not improve survival. Used selectively in patients with persistent symptoms despite optimal medical therapy or in those with concomitant atrial fibrillation.

Hydralazine and Isosorbide Dinitrate: A combination vasodilator therapy that can be beneficial in African American patients with HFrEF who remain symptomatic despite optimal medical therapy, or in patients who cannot tolerate ACEIs or ARBs.

Ivabradine: Reduces heart rate by inhibiting the If channel in the sinoatrial node. Can be used in stable, symptomatic HFrEF patients with reduced LVEF, who are in sinus rhythm with a heart rate ≥ 70 bpm despite maximally tolerated beta-blocker therapy.

Management of HFpEF:

Management of HFpEF is more challenging as therapies proven to reduce mortality in HFrEF have not shown the same benefit. Treatment focuses on managing comorbidities and controlling symptoms.

Control of Hypertension: Aggressive blood pressure control is crucial.

Management of Atrial Fibrillation: Rate and rhythm control are important.

Management of Diabetes, Obesity, and Sleep Apnea: Addressing these comorbidities is essential.

Diuretics: Used to manage congestion and symptoms of fluid overload.

SGLT2 Inhibitors: Recent evidence suggests SGLT2 inhibitors are beneficial in reducing heart failure hospitalizations in patients with HFpEF.

Aldosterone Antagonists: May be considered in select patients with HFpEF to reduce hospitalizations.

Device Therapy:

Implantable Cardioverter-Defibrillator (ICD): Recommended for primary and secondary prevention of sudden cardiac death in select patients with HFrEF and significantly reduced LVEF, based on guidelines.

Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy (CRT): A pacing device that resynchronizes the contraction of the left and right ventricles. Indicated in select patients with HFrEF, reduced LVEF, and a wide QRS complex on ECG, which indicates ventricular dyssynchrony. CRT can improve symptoms, exercise tolerance, and survival.

Surgical and Interventional Procedures:

Coronary Revascularization: Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) may be necessary in patients with significant coronary artery disease causing heart failure.

Valvular Surgery or Intervention: Repair or replacement of diseased heart valves can significantly improve cardiac function.

Left Ventricular Assist Devices (LVADs): Mechanical pumps that assist the weakened left ventricle in pumping blood. Used as a bridge to transplantation, a destination therapy in patients ineligible for transplantation, or as a bridge to recovery in some cases.

Heart Transplantation: The definitive treatment for select patients with end-stage, refractory CHF who meet specific criteria.

9. Prognosis and Complications

CHF is a progressive disease with a variable prognosis depending on the underlying cause, severity, comorbidities, and response to treatment.

Prognosis: Generally poor, especially in advanced stages. Factors associated with worse prognosis include older age, lower LVEF, higher NYHA class, elevated BNP levels, renal dysfunction, and presence of comorbidities.

Complications:

Acute Decompensated Heart Failure: Worsening of symptoms requiring urgent medical attention and often hospitalization.

Arrhythmias: Atrial fibrillation, ventricular tachycardia, and ventricular fibrillation are common and can lead to palpitations, syncope, or sudden cardiac death.

Renal Dysfunction: Cardiorenal syndrome, where impaired cardiac function leads to impaired renal function, is common.

Cachexia: Significant unintentional weight loss and muscle wasting seen in advanced CHF.

Thromboembolic Events: Increased risk of blood clots due to sluggish blood flow in dilated heart chambers, leading to stroke or pulmonary embolism.

Depression and Anxiety: Common psychological comorbidities that can affect quality of life and adherence to treatment.

10. Patient Education and Self-Care

Effective patient education and engagement in self-care are critical components of CHF management.

Understanding the Condition: Patients should understand what heart failure is, its causes, and its progressive nature.

Medication Adherence: Emphasizing the importance of taking medications as prescribed, understanding their purpose, and potential side effects.

Symptom Monitoring: Teaching patients to recognize worsening symptoms (e.g., increased dyspnea, weight gain, swelling) and to seek medical attention promptly. Daily weight monitoring is a key self-care behavior.

Dietary Modifications: Educating on sodium and fluid restrictions.

Activity Level: Providing guidance on appropriate levels of physical activity and the benefits of exercise.

Smoking and Alcohol Cessation: Reinforcing the importance of avoiding these substances.

Vaccinations: Recommending influenza and pneumococcal vaccinations to reduce the risk of respiratory infections that can exacerbate CHF.

Follow-up Care: Stressing the importance of regular medical appointments.

Related Topics

We are a supportive platform dedicated to empowering student nurses and midwives through quality educational resources, career guidance, and a vibrant community. Join us to connect, learn, and grow in your healthcare journey

Quick Links

Our Courses

Legal / Policies

Get in Touch

(+256) 790 036 252

(+256) 748 324 644

Info@nursesonlinediscussion.com

Kampala ,Uganda

© 2025 Nurses online discussion. All Rights Reserved | Design & Developed by Opensigma