circulatory system

Subtopic:

Embolism

An embolism is the sudden blocking of an artery, vein, or lymphatic vessel by an embolus – a mass of material that travels through the bloodstream or lymphatic system and lodges in a vessel, obstructing blood flow. The term “embolus” comes from the Greek word meaning “plug.” Embolism is a significant cause of morbidity and mortality, leading to tissue ischemia, infarction, and organ damage depending on the location and size of the obstructed vessel.

While the most common type of embolus is a blood clot (thromboembolism), an embolus can be composed of various materials, including fat, air, amniotic fluid, tumor cells, foreign bodies, or bacterial vegetations.

Types of Emboli

Emboli are classified based on their composition:

Thromboembolism: The most common type, consisting of a dislodged blood clot (thrombus).

Fat Embolism: Particles of fat, often released into the bloodstream after long bone fractures, orthopedic surgery, or trauma.

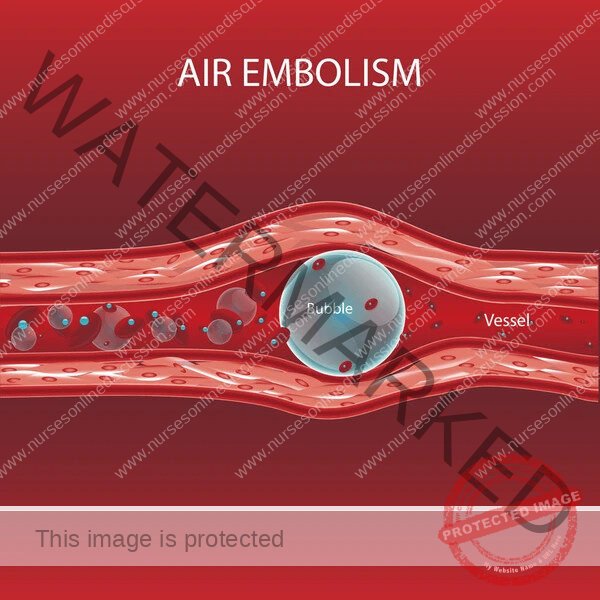

Air Embolism: Bubbles of air or gas entering the bloodstream. Can occur during surgery, trauma, central venous catheter insertion/removal, or decompression sickness (the “bends”).

Amniotic Fluid Embolism: Amniotic fluid, fetal cells, hair, or other debris entering the maternal circulation during labor or delivery. A rare but often catastrophic complication.

Cholesterol Embolism (Atheroembolism): Emboli composed of cholesterol crystals and atherosclerotic plaque debris. Typically occurs after procedures involving atherosclerotic arteries (e.g., angiography, angioplasty) or spontaneously from unstable plaques.

Tumor Embolism: Fragments of malignant tumors that break off and enter the circulation, leading to metastasis.

Bacterial/Septic Embolism: Emboli containing bacteria or infected material, often originating from infective endocarditis (infection of heart valves).

Foreign Body Embolism: Introduction of foreign material into the bloodstream, such as talc in intravenous drug users, or fragments of medical devices.

Sources of Emboli

The origin of an embolus depends on its type and the circulatory system involved (arterial or venous).

Sources of Thromboemboli:

Venous Thromboembolism (VTE): Thrombi originating in the venous system.

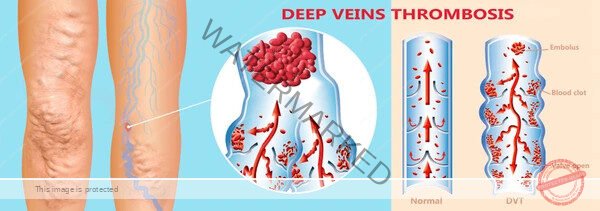

Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT): Clots forming in the deep veins, most commonly in the legs or pelvis. Risk factors are often related to Virchow’s triad: venous stasis (immobility, surgery, travel), endothelial injury (trauma, surgery, catheter insertion), and hypercoagulability (inherited or acquired clotting disorders, cancer, pregnancy, oral contraceptives).

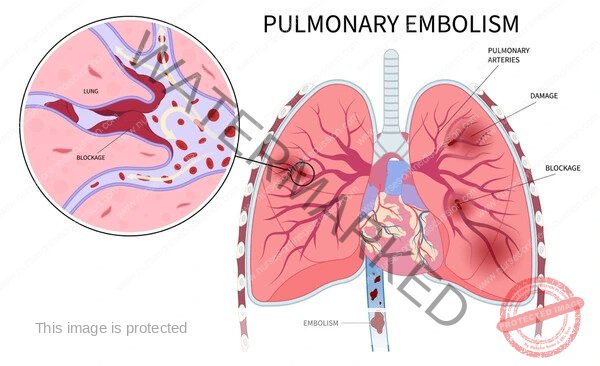

Pulmonary Embolism (PE): A VTE that travels to the pulmonary arteries, obstructing blood flow to the lungs. The vast majority of PEs originate from DVTs in the lower extremities.

Arterial Thromboembolism: Thrombi originating in the arterial system or the left side of the heart.

Left Atrium: Most commonly due to atrial fibrillation, where stagnant blood in the fibrillating atrium can clot.

Left Ventricle: Can occur after myocardial infarction (especially anterior wall MI) due to impaired wall motion (akinesis or dyskinesis) and endocardial damage, leading to mural thrombus formation. Also seen in dilated cardiomyopathy or ventricular aneurysms.

Valvular Heart Disease: Thrombi can form on diseased or artificial heart valves.

Atherosclerotic Plaques: Thrombi can form on ruptured or unstable atherosclerotic plaques in arteries (e.g., carotid arteries, aorta), leading to distal embolization.

Aneurysms: Thrombi can form within arterial aneurysms.

Sources of Other Emboli:

Fat Embolism: Fractures of long bones, pelvis, or multiple ribs; orthopedic surgery (e.g., joint replacement); severe trauma; liposuction; pancreatitis.

Air Embolism: Surgery (especially neurosurgery, cardiac surgery), central venous catheter insertion/removal, trauma (e.g., chest trauma), scuba diving (decompression sickness), mechanical ventilation, high-pressure injection injuries.

Amniotic Fluid Embolism: Labor and delivery.

Cholesterol Embolism: Invasive arterial procedures (angiography, angioplasty, aortic surgery), thrombolytic therapy, or spontaneously from unstable aortic plaques.

Tumor Embolism: Malignant neoplasms, particularly those that invade blood vessels.

Bacterial/Septic Embolism: Infective endocarditis, septic thrombophlebitis, abscesses.

Foreign Body Embolism: Intravenous drug use (e.g., injecting dissolved pills), trauma, fragmented medical devices (e.g., catheter tips, guidewires).

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of embolism involves the dislodgement and travel of an embolus through the circulation until it encounters a vessel too small to pass through, causing obstruction.

Venous Embolism: Emboli originating in the venous system travel through progressively larger veins towards the heart. They pass through the right atrium and right ventricle and then lodge in the pulmonary arteries, causing a pulmonary embolism (PE). The severity of PE depends on the size and number of emboli and the patient’s underlying cardiopulmonary status. Large emboli can cause massive obstruction, leading to acute right heart failure, shock, and sudden death. Smaller emboli can cause pulmonary infarction or dyspnea.

Arterial Embolism: Emboli originating in the arterial system or left heart chambers travel through progressively smaller arteries. They can lodge in arteries supplying various organs, including the brain (stroke), limbs (acute limb ischemia), kidneys (renal infarction), intestines (mesenteric ischemia), or other organs. The consequences depend on the affected organ and the extent of blood flow interruption. Acute arterial occlusion leads to ischemia and potentially infarction of the downstream tissue.

Paradoxical Embolism: A rare type where a venous embolus crosses from the right side of the heart to the left side through a defect in the atrial or ventricular septum (most commonly a patent foramen ovale – PFO) and then enters the arterial circulation, causing an arterial embolism (e.g., stroke). This occurs when right-sided pressures are elevated, forcing blood (and the embolus) across the defect.

The specific effects of different types of emboli vary:

Thromboembolism: Causes mechanical obstruction of blood flow. In PE, it also triggers the release of vasoactive substances that cause vasoconstriction in the pulmonary vasculature, further increasing pulmonary vascular resistance.

Fat Embolism: Fat globules obstruct capillaries in the lungs, brain, and other organs. They also trigger an inflammatory response, leading to endothelial damage and increased vascular permeability. This can result in the characteristic fat embolism syndrome (respiratory distress, neurological symptoms, petechial rash).

Air Embolism: Air bubbles can coalesce to form larger bubbles that obstruct blood flow. In the heart, a large air embolus in the right ventricle can cause an “air lock,” preventing blood from being pumped to the lungs. In the brain, air emboli can cause stroke.

Amniotic Fluid Embolism: Causes mechanical obstruction by particulate matter and triggers a severe inflammatory and coagulopathic response, leading to acute respiratory failure, hemodynamic collapse, and disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC).

Cholesterol Embolism: Cholesterol crystals and debris lodge in small arteries and arterioles, causing inflammation and obstruction, leading to microinfarctions in various organs (kidneys, skin, brain, gastrointestinal tract).

Clinical Manifestations

The signs and symptoms of embolism depend on the location of the obstruction and the type of embolus.

Pulmonary Embolism (PE):

Dyspnea: Sudden onset of shortness of breath (most common symptom).

Chest Pain: Often pleuritic (worse with breathing).

Tachypnea: Increased respiratory rate.

Tachycardia: Increased heart rate.

Cough: May be present, sometimes with blood-tinged sputum.

Hemoptysis: Coughing up blood.

Syncope or Presyncope: Fainting or near-fainting, especially with large PEs.

Hypotension and Shock: In massive PE.

Signs of DVT: Swelling, pain, tenderness, warmth, or redness in the leg (present in about half of PE cases).

Arterial Embolism (to a limb):

Often described by the “6 Ps”:

Pain: Sudden onset of severe pain in the affected limb.

Pallor: Paleness of the limb.

Pulselessness: Absence of pulses distal to the obstruction.

Paresthesia: Numbness or tingling sensation.

Paralysis: Weakness or inability to move the limb.

Poikilothermia: The limb feels cold compared to the unaffected limb.

Cerebral Embolism (Stroke):

Sudden onset of neurological deficits depending on the affected area of the brain, such as:

Weakness or numbness in the face, arm, or leg, usually on one side of the body.

Difficulty speaking or understanding speech (aphasia).

Vision problems in one or both eyes.

Dizziness, loss of balance or coordination.

Sudden severe headache.

Mesenteric Embolism:

Severe abdominal pain, often out of proportion to physical findings.

Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea.

Bloody stools.

Abdominal distension.

Renal Embolism:

Flank pain.

Hematuria (blood in the urine).

Acute kidney injury.

Fat Embolism Syndrome:

Onset typically 24-72 hours after the inciting event.

Respiratory Distress: Hypoxemia, dyspnea, tachypnea.

Neurological Symptoms: Confusion, agitation, altered level of consciousness, seizures.

Petechial Rash: Small, pinpoint hemorrhages, typically appearing on the upper chest, neck, axillae, and conjunctivae.

Air Embolism:

Symptoms vary depending on the amount and location of air.

Venous Air Embolism: Dyspnea, chest pain, hypotension, tachycardia, mill wheel murmur (a churning sound heard over the heart).

Arterial Air Embolism: Neurological deficits (stroke symptoms), myocardial ischemia, skin mottling.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of embolism is based on clinical suspicion, risk factors, and diagnostic tests.

Clinical Assessment: Detailed history of symptoms and potential risk factors. Physical examination to look for signs of obstruction (e.g., absent pulses, neurological deficits) or underlying sources (e.g., signs of DVT).

Laboratory Tests:

D-dimer: A blood test that measures a degradation product of fibrin. Elevated levels suggest the presence of a blood clot, but a negative D-dimer can help rule out VTE in low-risk patients. It is not specific for embolism.

Complete blood count, electrolytes, renal function tests, liver function tests.

Arterial blood gases (in suspected PE) to assess oxygenation.

Imaging Studies:

Pulmonary Embolism:

CT Pulmonary Angiography (CTPA): The gold standard for diagnosing PE. It involves injecting contrast dye and taking CT images of the pulmonary arteries to visualize emboli.

Ventilation-Perfusion (V/Q) Scan: Can be used if CTPA is contraindicated (e.g., renal dysfunction, contrast allergy). Compares areas of the lung that are ventilated with air to areas that are perfused with blood. Mismatches can indicate PE.

Lower Extremity Ultrasound: Used to diagnose DVT, which is often the source of PE.

Arterial Embolism (Limb):

Duplex Ultrasound: Can visualize the embolus and assess blood flow in the affected artery.

CT Angiography or MR Angiography: Provide detailed images of the arterial tree.

Invasive Angiography: Can confirm the diagnosis and allow for intervention.

Cerebral Embolism (Stroke):

Non-contrast Head CT: Performed urgently to rule out hemorrhagic stroke.

CT Angiography or MR Angiography of the Head and Neck: To identify arterial occlusions and potential sources (e.g., carotid stenosis).

Diffusion-Weighted MRI: Highly sensitive for detecting acute ischemic stroke.

Echocardiography (Transthoracic or Transesophageal): To identify cardiac sources of emboli (e.g., atrial thrombus, valvular vegetation, PFO).

Mesenteric Embolism:

CT Angiography of the Abdomen: The preferred imaging modality.

Renal Embolism:

CT Angiography of the Abdomen: Can visualize the embolus in the renal artery.

Fat Embolism Syndrome: Diagnosis is primarily clinical based on the presence of the characteristic triad (respiratory, neurological, petechial rash) after an inciting event. Imaging (chest X-ray, head CT/MRI) may show non-specific findings.

Air Embolism: Imaging (CT, ultrasound) may show air bubbles in vessels. Clinical context is crucial.

Management

Management of embolism depends on the type of embolus, the location of the obstruction, the severity of symptoms, and the patient’s overall condition.

General Principles:

Supportive Care: Maintaining airway, breathing, and circulation (ABCs). Oxygen therapy, fluid resuscitation, and vasopressors may be needed in severe cases.

Pain Management: Essential, especially in arterial embolism to a limb.

Specific Management Strategies:

Thromboembolism:

Anticoagulation: The cornerstone of treatment for VTE and often used in arterial embolism to prevent further clot formation and allow the body’s own fibrinolytic system to break down the existing clot. Medications include heparin (unfractionated or low molecular weight), fondaparinux, warfarin, and direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs – e.g., rivaroxaban, apixaban, dabigatran, edoxaban).

Thrombolysis (Fibrinolysis): Administration of medications (e.g., alteplase) that dissolve blood clots. Reserved for severe, life-threatening emboli (e.g., massive PE with hemodynamic instability, acute ischemic stroke within a specific time window) due to the risk of bleeding.

Embolectomy: Surgical or catheter-based removal of the embolus.

Surgical Embolectomy: May be performed for large arterial emboli in limbs or for massive PE in select cases.

Catheter-Directed Thrombectomy/Thrombolysis: Minimally invasive procedures where a catheter is inserted into the affected vessel to remove the clot mechanically or deliver thrombolytic agents directly to the clot.

Inferior Vena Cava (IVC) Filter: A device placed in the IVC to trap clots migrating from the legs to the lungs, preventing PE. Generally used in patients with contraindications to anticoagulation or recurrent PE despite anticoagulation.

Fat Embolism: Primarily supportive care. No specific treatment to remove the fat emboli. Management includes oxygenation, mechanical ventilation if needed, hemodynamic support, and fracture stabilization.

Air Embolism:

Position the patient in the left lateral decubitus position with the head down (Trendelenburg position) to trap air in the right ventricle and prevent it from entering the pulmonary artery.

Administer 100% oxygen.

Aspiration of air from the right ventricle via a central venous catheter may be attempted.

Hyperbaric oxygen therapy may be beneficial in arterial air embolism.

Amniotic Fluid Embolism: Primarily supportive care, including respiratory and hemodynamic support, and management of coagulopathy (DIC) with blood products.

Cholesterol Embolism: Primarily supportive care and aggressive management of risk factors (e.g., statins). No specific treatment to remove the cholesterol crystals.

Tumor Embolism: Treatment of the underlying malignancy.

Bacterial/Septic Embolism: Treatment of the underlying infection with antibiotics. Surgical intervention may be needed to remove infected vegetations or abscesses.

Foreign Body Embolism: Removal of the foreign body if possible and accessible.

Prevention

Preventing embolism is crucial, especially for the most common type, thromboembolism.

Prevention of Venous Thromboembolism (VTE):

Mechanical Prophylaxis: Early ambulation after surgery, compression stockings, intermittent pneumatic compression devices.

Pharmacological Prophylaxis: Anticoagulants (e.g., low molecular weight heparin, unfractionated heparin, fondaparinux, DOACs) in patients at high risk (e.g., post-surgery, hospitalized medical patients with reduced mobility, trauma).

Prevention of Arterial Embolism:

Anticoagulation: In patients with atrial fibrillation or mechanical heart valves.

Antiplatelet Therapy: In patients with atherosclerosis to prevent thrombus formation on plaques.

Management of Risk Factors: Aggressive control of hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, and smoking cessation to prevent atherosclerosis progression and plaque rupture.

Carotid Endarterectomy or Stenting: In patients with significant carotid stenosis to reduce stroke risk.

Left Atrial Appendage Closure: In select patients with atrial fibrillation who are not candidates for long-term anticoagulation.

Prognosis and Complications

The prognosis of embolism varies widely depending on the type, size, location, and number of emboli, the underlying cause, and the patient’s overall health.

Prognosis:

Massive PE and amniotic fluid embolism have high mortality rates.

Stroke and acute limb ischemia can lead to significant long-term disability or death.

Small, peripheral emboli may be asymptomatic or cause limited tissue damage.

Complications:

Tissue infarction and organ damage (e.g., pulmonary infarction, stroke, limb gangrene, kidney failure).

Pulmonary hypertension (chronic complication of recurrent or unresolved PE).

Post-thrombotic syndrome (chronic pain, swelling, and skin changes in the affected limb after DVT).

Recurrence of embolism.

Bleeding complications from anticoagulant or thrombolytic therapy.

Related Topics

Get in Touch

(+256) 790 036 252

(+256) 748 324 644

Info@nursesonlinediscussion.com

Kampala ,Uganda

© 2025 Nurses online discussion. All Rights Reserved Design & Developed by Opensigma.co