Specific Surgical Infections

Subtopic:

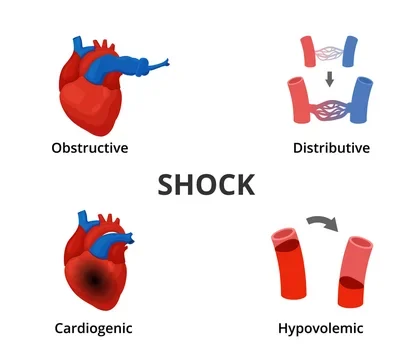

Surgical Shock

Surgical shock is a medical state of insufficient blood flow, or perfusion, to the body’s organs and tissues.

This inadequate circulation can lead to cellular damage and impaired organ function. Surgical shock can arise as a complication during or following surgical procedures. Shock is broadly categorized into different types based on its underlying cause. A failure to promptly identify and address the root cause of any type of shock can result in irreversible damage to multiple organs, organ failure, and potentially death.

Common forms of shock encountered in surgical settings include:

Hypovolemic Shock

Hypovolemic shock occurs when there is a significant reduction in the volume of circulating blood. In the context of surgery, a frequent cause is blood loss.

However, other factors such as severe vomiting, diarrhea, or fluid shifting out of blood vessels into surrounding tissues (due to inflammation, for example) can also lead to decreased blood volume. Insufficient blood volume impairs the delivery of oxygen and nutrients to organs and tissues, resulting in their suboptimal function and the clinical manifestations of shock.

Cardiogenic Shock

Cardiogenic shock results from the heart’s inability to effectively pump blood into the circulatory system. This can be due to mechanical issues, abnormal heart rhythms (arrhythmias), or disease of the heart muscle itself (cardiomyopathy). Mechanical problems might involve a heart valve not functioning correctly, causing blood to flow backward instead of moving forward efficiently through the heart’s chambers and into the bloodstream.

Arrhythmias can disrupt the coordinated electrical signals that govern the heart’s muscular contractions, reducing its pumping efficiency. Cardiomyopathy, often a chronic condition affecting the heart muscle’s structure and function, can predispose a patient to cardiogenic shock, particularly when the stress of surgery is superimposed on an already weakened heart.

Obstructive Shock

Obstructive shock is caused by a physical blockage that impedes blood flow, thereby reducing the supply of oxygen and nutrients to organs and tissues and leading to dysfunction. Potential causes of obstructive shock include blood clots in the lungs (pulmonary embolism), accumulation of fluid around the heart that restricts its movement (cardiac tamponade), or a collapsed lung that puts pressure on blood vessels (tension pneumothorax).

Other arterial obstructions, such as narrowing (stenosis) or blockages caused by traveling clots or material (embolism) or clots formed in place (thrombosis), can also lead to obstructive shock. Blood clots are a recognized complication during and after surgical procedures, sometimes resulting in deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism.

Distributive Shock

Distributive shock is characterized by widespread dilation of blood vessels throughout the body. This leads to a significant drop in blood pressure and inadequate tissue perfusion. This category includes several subtypes:

- Anaphylactic Shock: A severe, potentially life-threatening allergic reaction that can occur in surgical settings due to exposure to a medication or substance the patient is allergic to. This triggers the release of inflammatory chemicals like histamine, causing widespread vasodilation and dysfunction of multiple organ systems.

- Septic Shock: This can develop in surgical patients due to an underlying infection. While surgery is often avoided in the presence of active infection, it may be necessary to remove infected or dead tissue. In septic shock, the body’s response to the infection causes widespread inflammation and vasodilation, leading to drastically reduced blood pressure and organ hypoperfusion.

- Neurogenic Shock: This type of shock results from damage to the spinal cord, which disrupts the autonomic nervous system’s ability to regulate blood vessel tone and maintain blood pressure. This loss of regulation leads to widespread vasodilation and a drop in systemic blood pressure, compromising blood flow to tissues.

Diagnosis of Shock

Diagnosing shock is primarily based on a clinical assessment by a medical professional, involving observation of patient symptoms and a physical examination. Shock can exist in either a compensated or decompensated state. In compensated shock, the body attempts to maintain adequate blood flow to vital organs by working harder, often showing only subtle changes in vital signs despite significant physiological stress. For instance, in compensated hypovolemic shock, heart rate may be slightly elevated, but blood pressure might remain within the normal range as the heart pumps faster to compensate for reduced volume. Prompt recognition of compensated shock is critical to prevent it from progressing.

Decompensated shock occurs when the body’s compensatory mechanisms are overwhelmed and fail to maintain adequate function. Clinical signs and symptoms become more pronounced and readily identifiable. In decompensated hypovolemic shock, blood pressure drops significantly, heart rate increases further, and there are clear signs of inadequate blood flow to organs, such as confusion (due to insufficient oxygen to the brain) or decreased urine output (as the kidneys are not receiving enough blood flow to function properly). These observable signs and symptoms provide vital clues for healthcare providers to diagnose shock, identify its underlying cause, and initiate timely treatment.

Treatment of Surgical Shock

The management of surgical shock, and shock in general, is dependent on the identified underlying cause. The primary objective of treatment is to restore adequate blood flow and oxygen delivery to the tissues. Common interventions may include administering intravenous fluids to increase blood volume, controlling sources of bleeding, transfusing blood products to replace lost blood, using medications to enhance the heart’s pumping strength (inotropes), and administering medications to raise blood pressure (vasopressors).

Medical professionals rely on the clinical presentation, patient history, and ongoing monitoring of signs and symptoms to diagnose shock, determine its cause, and select appropriate treatments to prevent severe complications like multiple organ failure and death.

Get in Touch

(+256) 790 036 252

(+256) 748 324 644

Info@nursesonlinediscussion.com

Kampala ,Uganda

© 2025 Nurses online discussion. All Rights Reserved Design & Developed by Opensigma.co