Digestive System

Subtopic:

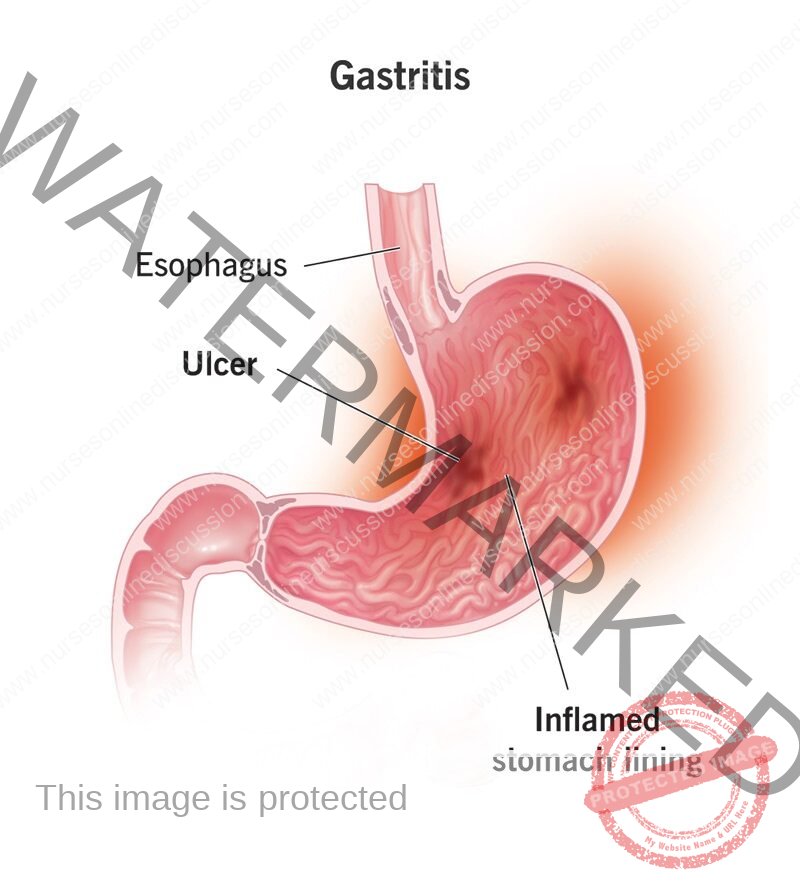

Gastritis

Gastritis is a common condition characterized by inflammation of the stomach lining, also known as the gastric mucosa. This inflammation can be acute, occurring suddenly and lasting for a short period, or chronic, developing gradually and persisting over time. While often associated with symptoms like indigestion, nausea, and abdominal pain, gastritis can sometimes be asymptomatic. Understanding the underlying causes and mechanisms of gastritis is crucial for appropriate diagnosis and management, as chronic forms can lead to serious complications, including peptic ulcers, bleeding, and an increased risk of gastric cancer.

Definition and Classification

Gastritis is defined histologically by the presence of inflammatory cells in the gastric mucosa. Clinically, the term is often used more broadly to describe symptoms of upper abdominal discomfort or pain, although these symptoms can be caused by various other conditions.

Gastritis can be classified based on its duration and underlying cause:

1. Acute Gastritis:

Sudden onset of inflammation.

Often caused by acute exposure to irritants or infectious agents.

Histologically characterized by neutrophil infiltration.

2. Chronic Gastritis:

Develops gradually over time.

Often associated with long-term exposure to causative factors or autoimmune processes.

Histologically characterized by lymphocyte and plasma cell infiltration, and potentially mucosal atrophy and metaplasia.

Chronic gastritis is further classified based on its etiology and location:

Type A (Autoimmune Gastritis): Affects primarily the fundus and body of the stomach. Caused by autoimmune destruction of parietal cells, leading to decreased acid production and intrinsic factor deficiency (pernicous anemia).

Type B (Helicobacter pylori Gastritis): The most common type, affecting primarily the antrum but can extend to the body. Caused by infection with the bacterium Helicobacter pylori.

Type C (Chemical Gastritis): Caused by chemical irritants, most commonly chronic bile reflux or NSAID use. Affects primarily the antrum.

Other less common types include:

Reactive Gastropathy: Mucosal damage and regeneration with minimal inflammation, often due to chemical irritants like NSAIDs or bile.

Infectious Gastritis (Non-H. pylori): Caused by other bacteria, viruses, fungi, or parasites, particularly in immunocompromised individuals.

Granulomatous Gastritis: Associated with systemic diseases like Crohn’s disease, sarcoidosis, or infections like tuberculosis.

Eosinophilic Gastritis: Characterized by eosinophil infiltration, often associated with allergic disorders.

Etiology and Risk Factors

The causes of gastritis are numerous and varied:

1. Helicobacter pylori Infection:

The most common cause of chronic gastritis globally.

H. pylori is a spiral-shaped bacterium that colonizes the gastric mucosa.

It causes chronic inflammation, which can lead to peptic ulcers, gastric atrophy, intestinal metaplasia, and significantly increases the risk of gastric cancer and MALT lymphoma.

Transmission is typically fecal-oral or oral-oral.

2. Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs):

A common cause of acute and chronic gastritis and peptic ulcers.

NSAIDs damage the gastric mucosa by inhibiting cyclooxygenase (COX) enzymes, which are necessary for the production of prostaglandins. Prostaglandins play a protective role in the stomach lining by promoting mucus and bicarbonate secretion, maintaining mucosal blood flow, and inhibiting acid secretion.

Risk factors for NSAID-induced gastritis include high dose, prolonged use, concomitant use of corticosteroids or anticoagulants, age >65, and history of peptic ulcer disease.

3. Alcohol:

Excessive alcohol consumption can irritate and erode the gastric mucosa, leading to acute gastritis.

4. Stress:

Severe physiological stress (e.g., critical illness, major surgery, burns, head trauma) can lead to stress-induced gastritis and ulcers, particularly in the fundus and body of the stomach. The mechanisms include reduced mucosal blood flow and impaired mucosal defense.

5. Autoimmune Gastritis (Type A):

An autoimmune disorder where the body produces antibodies against parietal cells and intrinsic factor.

Leads to atrophy of the gastric body and fundus, impaired acid secretion (hypochlorhydria or achlorhydria), hypergastrinemia (due to lack of negative feedback from acid), and vitamin B12 deficiency (pernicious anemia) due to lack of intrinsic factor.

Increases the risk of gastric carcinoid tumors and adenocarcinoma.

6. Bile Reflux:

Reflux of bile from the duodenum into the stomach, often after gastric surgery (e.g., gastrectomy, gastroenterostomy) or due to pyloric sphincter dysfunction.

Bile acids can damage the gastric mucosal barrier, leading to chemical gastritis.

7. Infections (Non-H. pylori):

Less common, but can occur, especially in immunocompromised individuals.

Examples include viral infections (e.g., Cytomegalovirus, Herpes Simplex Virus), fungal infections (Candida), and parasitic infections.

8. Other Causes:

Smoking: Damages the gastric mucosa and impairs healing.

Dietary Factors: While not a direct cause of chronic gastritis, consumption of spicy foods, acidic foods, and caffeine can exacerbate symptoms.

Radiation Therapy: Radiation to the upper abdomen can cause radiation gastritis.

Crohn’s Disease: Can affect any part of the gastrointestinal tract, including the stomach, causing granulomatous gastritis.

Sarcoidosis: A multi-system inflammatory disease that can involve the stomach.

Amyloidosis: Deposition of amyloid protein in the gastric wall.

Eosinophilic Gastroenteritis: Infiltration of eosinophils into the stomach wall.

Pathophysiology

Gastritis results from an imbalance between factors that protect the gastric mucosa and factors that damage it.

Protective Factors:

Mucus Layer: A thick layer of mucus secreted by surface epithelial cells provides a physical barrier against acid and pepsin.

Bicarbonate Secretion: Bicarbonate ions trapped within the mucus layer neutralize acid that penetrates the mucus.

Epithelial Cell Turnover: Rapid regeneration of gastric epithelial cells helps repair damage.

Mucosal Blood Flow: Adequate blood flow provides oxygen and nutrients and removes acid and toxins.

Prostaglandins: These lipid compounds stimulate mucus and bicarbonate secretion, maintain mucosal blood flow, and inhibit acid secretion.

Damaging Factors:

Gastric Acid and Pepsin: The stomach’s own secretions, while essential for digestion, can damage the mucosa if protective mechanisms are compromised.

Helicobacter pylori: Produces enzymes (urease, proteases) and toxins (VacA, CagA) that damage the mucosal barrier and elicit an inflammatory response. Urease converts urea to ammonia, which neutralizes acid locally, allowing the bacteria to survive in the acidic environment.

NSAIDs: Inhibit prostaglandin synthesis, reducing mucosal protection.

Bile Acids: Disrupt the lipid bilayer of cell membranes, increasing mucosal permeability to acid.

Alcohol: Damages the mucosal barrier.

Ischemia: Reduced blood flow (e.g., during stress) impairs protective mechanisms.

Autoantibodies: In autoimmune gastritis, antibodies destroy parietal cells, leading to mucosal atrophy.

When damaging factors overwhelm protective mechanisms, inflammation occurs, characterized by infiltration of inflammatory cells (neutrophils in acute, lymphocytes and plasma cells in chronic). Prolonged inflammation can lead to mucosal erosion (shallow defects) or ulceration (deeper defects extending into the submucosa or muscularis propria). Chronic inflammation can also cause architectural changes in the mucosa, including atrophy (loss of glands) and intestinal metaplasia (replacement of gastric epithelium with intestinal-like epithelium), which are precancerous lesions.

Clinical Manifestations

The symptoms of gastritis are often non-specific and can vary depending on the type and severity of inflammation. Some individuals with gastritis are asymptomatic.

Common symptoms include:

Epigastric Pain or Discomfort: A burning or aching pain in the upper abdomen, often described as indigestion.

Nausea: Feeling sick to the stomach.

Vomiting: May occur, sometimes with blood (hematemesis) if there is significant mucosal erosion or ulceration.

Bloating: Feeling of fullness or distension in the abdomen.

Loss of Appetite: Reduced desire to eat.

Feeling of Fullness after Eating (Early Satiety): Feeling full after consuming only a small amount of food.

Weight Loss: May occur in chronic or severe cases due to reduced food intake or malabsorption (though less common).

Hematemesis or Melena: Vomiting blood or passing black, tarry stools, indicating upper gastrointestinal bleeding. This is a more serious symptom and requires urgent medical attention.

Specific types of gastritis may have additional manifestations:

H. pylori Gastritis: Often asymptomatic or causes chronic dyspepsia. Can lead to peptic ulcers.

Autoimmune Gastritis: May be asymptomatic initially but can lead to symptoms of anemia (fatigue, weakness, pallor) due to vitamin B12 deficiency.

Acute Gastritis (e.g., NSAID-induced): May cause sudden onset of epigastric pain, nausea, vomiting, and potentially bleeding.

Physical examination in patients with gastritis is often normal, although there may be tenderness in the epigastric region.

Diagnosis

Diagnosing gastritis typically involves a combination of medical history, physical examination, and diagnostic tests.

Medical History and Physical Examination: As described above, these help identify potential causes and assess symptoms.

Endoscopy with Biopsy: This is the most definitive method for diagnosing gastritis and determining its cause and severity. An endoscope (a flexible tube with a camera) is inserted through the mouth to visualize the gastric mucosa. Biopsies (small tissue samples) are taken from different parts of the stomach and examined under a microscope to assess the presence and type of inflammation, identify H. pylori, and detect any precancerous changes (atrophy, metaplasia) or malignancy.

Helicobacter pylori Testing: Several methods are available to detect H. pylori infection:

Urea Breath Test: The patient ingests a substance containing labeled urea. If H. pylori is present, it breaks down the urea, releasing labeled carbon dioxide, which is detected in the breath.

Stool Antigen Test: Detects H. pylori antigens in the stool.

Blood Antibody Test: Detects antibodies to H. pylori in the blood. This test indicates exposure but does not distinguish between active and past infection and is not used to confirm eradication after treatment.

Biopsy-based Tests: Rapid Urease Test, histology (examination of biopsy under microscope), and culture of biopsy samples.

Blood Tests: May be performed to check for anemia (especially in chronic gastritis or bleeding), vitamin B12 levels (in suspected autoimmune gastritis), and sometimes markers of inflammation.

Barium Swallow (Upper GI Series): While less commonly used for diagnosing gastritis itself, it can help visualize the stomach and duodenum and detect ulcers or other structural abnormalities.

Management

Management of gastritis depends on the underlying cause. The primary goals are to eliminate the causative agent or factor, reduce gastric acid production, relieve symptoms, and prevent complications.

1. Treatment of Underlying Cause:

H. pylori Infection: Requires eradication therapy, typically a combination of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) and two or more antibiotics for 7-14 days. Eradication success should be confirmed after treatment using a urea breath test or stool antigen test.

NSAID-Induced Gastritis: Discontinue the NSAID if possible. If NSAID use is necessary, use the lowest effective dose, consider a COX-2 selective NSAID (which have a lower risk of gastric complications but potential cardiovascular risks), and/or co-prescribe a PPI or misoprostol to protect the gastric mucosa.

Autoimmune Gastritis: No specific treatment for the autoimmune process itself. Management focuses on managing complications, particularly vitamin B12 deficiency (requiring lifelong B12 injections) and surveillance for gastric cancer and carcinoid tumors.

Bile Reflux Gastritis: May involve medications to improve gastric motility or bind bile acids, and sometimes surgery in severe cases.

Other Infections: Treat with appropriate antimicrobial agents.

Addressing Other Causes: Manage underlying systemic diseases, avoid alcohol and smoking, and minimize exposure to other irritants.

2. Reduction of Gastric Acid:

Proton Pump Inhibitors (PPIs): These are the most effective medications for reducing gastric acid production (e.g., omeprazole, lansoprazole, pantoprazole, esomeprazole). They are widely used in the treatment of gastritis and associated conditions.

H2-Receptor Blockers (H2RAs): Less potent than PPIs but also reduce acid production (e.g., ranitidine – though largely withdrawn due to safety concerns, famotidine, cimetidine).

Antacids: Provide rapid but short-lived relief by neutralizing existing stomach acid.

3. Symptom Relief:

Acid-reducing medications help alleviate pain and discomfort.

Antiemetics can be used to manage nausea and vomiting.

4. Lifestyle and Dietary Modifications:

While dietary factors are not primary causes, avoiding foods and beverages that exacerbate symptoms (e.g., spicy foods, acidic foods, caffeine, alcohol) may be helpful for some individuals.

Eating smaller, more frequent meals may reduce gastric distension and discomfort.

Stress reduction techniques may be beneficial, particularly for stress-related gastritis.

Complications

Chronic gastritis, particularly H. pylori gastritis and autoimmune gastritis, can lead to several complications:

Peptic Ulcers: Erosions that penetrate through the muscularis mucosa. Gastric ulcers are more common in the antrum in H. pylori gastritis and in the body in NSAID-induced gastritis. Duodenal ulcers are strongly associated with H. pylori.

Gastrointestinal Bleeding: Can range from chronic occult bleeding leading to iron deficiency anemia to acute, life-threatening hemorrhage from ulcers or severe erosions.

Gastric Atrophy: Loss of gastric glands, leading to reduced acid and enzyme secretion.

Intestinal Metaplasia: Replacement of gastric epithelium with intestinal-like epithelium. Both atrophy and metaplasia are considered precancerous lesions.

Gastric Cancer (Adenocarcinoma): Chronic H. pylori gastritis significantly increases the risk of developing gastric adenocarcinoma, particularly the intestinal type. Autoimmune gastritis also increases this risk.

Gastric MALT Lymphoma: A type of lymphoma that arises in the stomach mucosa, strongly associated with H. pylori infection. Eradication of H. pylori can often lead to regression of MALT lymphoma.

Pernicious Anemia: A complication of autoimmune gastritis due to vitamin B12 deficiency.

We are a supportive platform dedicated to empowering student nurses and midwives through quality educational resources, career guidance, and a vibrant community. Join us to connect, learn, and grow in your healthcare journey

Quick Links

Our Courses

Legal / Policies

Get in Touch

(+256) 790 036 252

(+256) 748 324 644

Info@nursesonlinediscussion.com

Kampala ,Uganda

© 2025 Nurses online discussion. All Rights Reserved | Design & Developed by Opensigma