Digestive System

Subtopic:

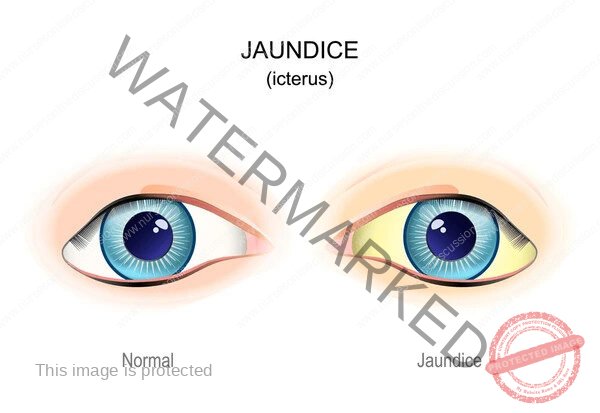

Jaundice

Jaundice, also known as icterus, is a clinical sign characterized by a yellowish discoloration of the skin, sclerae (whites of the eyes), and mucous membranes. This discoloration is caused by hyperbilirubinemia, which is an elevated level of bilirubin in the blood. Bilirubin is a yellow pigment that is a byproduct of the breakdown of heme, primarily from aged red blood cells. While jaundice itself is a symptom, it indicates an underlying problem with bilirubin metabolism, transport, or excretion, often related to liver, gallbladder, or blood disorders.

Bilirubin Metabolism

Understanding bilirubin metabolism is fundamental to comprehending the causes of jaundice. The process involves several steps:

Production: Heme, primarily from senescent red blood cells (about 80%), but also from ineffective erythropoiesis and other heme-containing proteins (e.g., myoglobin, cytochromes), is broken down in the reticuloendothelial system (mainly in the spleen, liver, and bone marrow). Heme is converted to biliverdin by heme oxygenase, and then biliverdin is reduced to unconjugated bilirubin by biliverdin reductase.

Transport: Unconjugated bilirubin (also called indirect bilirubin) is lipid-soluble and insoluble in water. It is transported in the blood bound to albumin.

Hepatic Uptake: The albumin-bilirubin complex travels to the liver. In the liver sinusoids, unconjugated bilirubin is released from albumin and taken up by hepatocytes via specific membrane transporters (e.g., OATP1B1, OATP1B3).

Conjugation: Within hepatocytes, unconjugated bilirubin is conjugated with glucuronic acid by the enzyme uridine 5′-diphospho-glucuronosyltransferase 1A1 (UGT1A1). This process converts lipid-soluble unconjugated bilirubin into water-soluble conjugated bilirubin (also called direct bilirubin).

Biliary Excretion: Conjugated bilirubin is actively transported from hepatocytes into the bile canaliculi via the multidrug resistance-associated protein 2 (MRP2). It then becomes a component of bile.

Intestinal Passage: Bile, containing conjugated bilirubin, is released into the small intestine. In the intestine, conjugated bilirubin is deconjugated by bacterial beta-glucuronidases and then converted by intestinal bacteria into urobilinogen.

Excretion:

Most urobilinogen is oxidized in the feces to stercobilin, which gives stool its characteristic brown color.

A small amount of urobilinogen is reabsorbed from the intestine into the portal circulation.

Most of the reabsorbed urobilinogen is taken up by the liver and re-excreted into the bile (enterohepatic circulation).

A small fraction of reabsorbed urobilinogen bypasses the liver and is excreted by the kidneys into the urine as urobilin, which contributes to the yellow color of urine.

Classification of Jaundice

Jaundice is typically classified based on the underlying mechanism causing hyperbilirubinemia, which often corresponds to where the problem occurs in the bilirubin metabolic pathway:

Pre-hepatic Jaundice:

Caused by increased production of unconjugated bilirubin, overwhelming the liver’s ability to conjugate and excrete it.

Characterized by elevated unconjugated bilirubin levels in the blood.

Liver function is typically normal, but it cannot keep up with the excessive bilirubin load.

Causes are primarily related to increased red blood cell breakdown (hemolysis) or ineffective erythropoiesis.

Hepatic Jaundice:

Caused by dysfunction of the liver itself, affecting its ability to take up, conjugate, or excrete bilirubin.

Can involve elevated unconjugated, conjugated, or mixed bilirubin levels, depending on the specific liver problem.

Reflects hepatocellular damage or impaired hepatic function.

Causes include various liver diseases.

Post-hepatic Jaundice (Obstructive Jaundice):

Caused by obstruction of the flow of conjugated bilirubin from the liver into the intestines.

Characterized by elevated conjugated bilirubin levels in the blood.

Bilirubin is conjugated normally by the liver but cannot be excreted into the bile ducts.

Causes are related to blockage of the bile ducts.

Etiology and Causes

The specific causes of jaundice vary depending on the classification:

Pre-hepatic Jaundice:

Hemolytic Anemias: Conditions leading to increased destruction of red blood cells, such as:

Genetic disorders (e.g., hereditary spherocytosis, sickle cell anemia, thalassemia, G6PD deficiency).

Autoimmune hemolytic anemia.

Transfusion reactions.

Hemolytic disease of the newborn (Rh or ABO incompatibility).

Malaria and other infections causing hemolysis.

Drugs or toxins causing hemolysis.

Ineffective Erythropoiesis: Premature destruction of red blood cell precursors in the bone marrow (e.g., megaloblastic anemia, thalassemia major).

Gilbert’s Syndrome: A common, benign genetic disorder causing reduced activity of the UGT1A1 enzyme, leading to mildly elevated unconjugated bilirubin, often exacerbated by stress, fasting, or illness.

Crigler-Najjar Syndrome: Rare genetic disorders with severely reduced or absent UGT1A1 activity, leading to severe unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia.

Hepatic Jaundice:

Acute Viral Hepatitis: Inflammation of the liver caused by viruses (Hepatitis A, B, C, D, E).

Chronic Hepatitis: Ongoing liver inflammation, often due to Hepatitis B or C, autoimmune hepatitis, or non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD).

Cirrhosis: Advanced scarring of the liver, often due to chronic viral hepatitis, alcohol abuse, or NAFLD, leading to impaired liver function.

Alcoholic Liver Disease: Liver damage caused by excessive alcohol consumption (fatty liver, alcoholic hepatitis, cirrhosis).

Drug-Induced Liver Injury: Liver damage caused by medications or toxins (e.g., acetaminophen overdose, certain antibiotics, herbal supplements).

Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD) / Non-Alcoholic Steatohepatitis (NASH): Fat accumulation in the liver, which can progress to inflammation and fibrosis.

Autoimmune Hepatitis: The body’s immune system attacks the liver.

Genetic Liver Disorders:

Hemochromatosis (iron overload).

Wilson’s disease (copper overload).

Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency.

Primary Biliary Cholangitis (PBC): An autoimmune disease affecting the small bile ducts within the liver.

Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis (PSC): A chronic disease causing inflammation and scarring of the bile ducts.

Liver Cancer: Primary liver cancer (hepatocellular carcinoma) or metastatic cancer to the liver.

Sepsis and Severe Illness: Can cause impaired liver function.

Post-hepatic Jaundice (Obstructive Jaundice):

Gallstones: Stones in the gallbladder that migrate into and block the common bile duct (choledocholithiasis).

Strictures: Narrowing of the bile ducts due to inflammation, surgery, or chronic pancreatitis.

Tumors:

Cancer of the head of the pancreas.

Cholangiocarcinoma (cancer of the bile ducts).

Ampullary cancer (cancer of the ampulla of Vater).

Metastatic cancer compressing the bile ducts.

Pancreatitis: Inflammation of the pancreas, particularly chronic pancreatitis, can compress the common bile duct.

Parasites: Rarely, parasites (e.g., Clonorchis sinensis) can obstruct the bile ducts.

Biliary Atresia: A rare congenital condition in infants where the bile ducts are blocked or absent.

Clinical Manifestations

The most obvious clinical manifestation of jaundice is the yellowish discoloration of the skin, sclerae, and mucous membranes. This is usually the first sign noticed. The intensity of the yellowing can vary depending on the level of bilirubin.

Other symptoms and signs that may accompany jaundice depend on the underlying cause:

Pre-hepatic Jaundice:

Symptoms of anemia: Fatigue, weakness, pallor.

Splenomegaly (enlarged spleen) due to increased red blood cell destruction.

Dark urine due to increased urobilinogen excretion (if liver function is normal).

Normal colored stool (unless there is a concomitant issue).

Hepatic Jaundice:

Symptoms of liver disease: Fatigue, weakness, loss of appetite, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain (especially in the upper right quadrant), dark urine (due to conjugated bilirubin excretion), pale or clay-colored stools (if there is significant cholestasis).

Other signs of chronic liver disease: Ascites (fluid in the abdomen), peripheral edema (swelling in the legs), spider angiomas (small, spider-like blood vessels on the skin), palmar erythema (reddening of the palms), gynecomastia (breast enlargement in men), easy bruising or bleeding (due to impaired synthesis of clotting factors), hepatic encephalopathy (confusion, altered mental status).

Post-hepatic Jaundice:

Pruritus (itching): Caused by the accumulation of bile salts in the skin.

Dark urine (due to conjugated bilirubin excretion).

Pale or clay-colored stools (acholic stools): Due to the absence of stercobilin in the feces.

Right upper quadrant abdominal pain: May be present if gallstones or inflammation are the cause.

Fever and chills: May indicate cholangitis (infection of the bile ducts), a medical emergency.

Weight loss: May occur with malignancy.

Courvoisier’s sign: A palpable, non-tender gallbladder, which may indicate malignant obstruction of the common bile duct.

Diagnosis

Diagnosing the cause of jaundice involves a systematic approach including medical history, physical examination, laboratory tests, and imaging studies.

Medical History:

Onset and duration of jaundice.

Presence of associated symptoms (pain, fever, itching, changes in urine or stool color, fatigue, weight loss).

History of viral hepatitis exposure, alcohol consumption, drug use (prescription, over-the-counter, herbal), travel history, family history of liver or blood disorders.

History of surgery, particularly abdominal surgery.

Physical Examination:

Assessment of the degree of jaundice (skin, sclerae, mucous membranes).

Examination for signs of chronic liver disease (ascites, edema, spider angiomas, palmar erythema).

Palpation of the abdomen for hepatomegaly (enlarged liver), splenomegaly (enlarged spleen), or a palpable gallbladder.

Assessment for signs of pruritus (scratch marks).

Evaluation of mental status (for hepatic encephalopathy).

Laboratory Tests:

Serum Bilirubin Levels: Measurement of total bilirubin, unconjugated (indirect) bilirubin, and conjugated (direct) bilirubin is crucial for classifying the type of jaundice.

Elevated unconjugated bilirubin suggests pre-hepatic or some hepatic causes.

Elevated conjugated bilirubin suggests post-hepatic or some hepatic causes (cholestasis).

Liver Enzymes:

Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and Aspartate aminotransferase (AST): Elevated in hepatocellular damage.

Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and Gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT): Elevated in cholestasis (impaired bile flow).

Other Liver Function Tests:

Serum albumin: Decreased in chronic liver disease.

Prothrombin time (PT) / International Normalized Ratio (INR): Prolonged in severe liver dysfunction (impaired synthesis of clotting factors).

Complete Blood Count (CBC) with Reticulocyte Count and Peripheral Blood Smear: To evaluate for anemia and signs of hemolysis (elevated reticulocyte count, abnormal red blood cell morphology).

Viral Hepatitis Serology: Tests for Hepatitis A, B, C, D, and E markers.

Autoimmune Markers: If autoimmune liver disease is suspected.

Genetic Tests: For suspected genetic disorders (e.g., Gilbert’s syndrome, hemochromatosis, Wilson’s disease).

Urine Bilirubin and Urobilinogen: Conjugated bilirubin is water-soluble and appears in the urine, making it dark. Urobilinogen is increased in pre-hepatic jaundice (if liver function is normal) and decreased or absent in complete biliary obstruction.

Imaging Studies:

Abdominal Ultrasound: Often the initial imaging test, useful for detecting gallstones, dilated bile ducts (suggesting obstruction), and assessing liver size and texture.

Computed Tomography (CT) Scan: Provides detailed images of the liver, pancreas, and bile ducts, useful for identifying tumors, pancreatitis, and other causes of obstruction.

Magnetic Resonance Cholangiopancreatography (MRCP): A non-invasive MRI technique that provides detailed images of the bile ducts and pancreatic duct, excellent for visualizing strictures, stones, and tumors.

Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography (ERCP): An invasive endoscopic procedure where contrast is injected into the bile ducts and pancreatic duct, allowing for visualization and therapeutic interventions (e.g., stone removal, stricture dilation, stent placement). Used when MRCP suggests obstruction or for therapeutic purposes.

Percutaneous Transhepatic Cholangiography (PTC): An invasive procedure where contrast is injected into the bile ducts through the skin, used when ERCP is not feasible or successful.

Liver Biopsy: May be necessary in some cases of hepatic jaundice to determine the specific cause and severity of liver disease, especially when the diagnosis is unclear from other tests.

Management

Management of jaundice is focused on treating the underlying cause.

Pre-hepatic Jaundice: Treatment is directed at the cause of increased red blood cell breakdown or ineffective erythropoiesis (e.g., managing hemolytic anemia, addressing underlying hematological disorders). Gilbert’s syndrome typically requires no specific treatment.

Hepatic Jaundice: Management depends on the specific liver disease (e.g., antiviral therapy for chronic viral hepatitis, corticosteroids for autoimmune hepatitis, supportive care and abstinence from alcohol for alcoholic liver disease, managing underlying metabolic disorders). Liver transplantation may be necessary for end-stage liver disease.

Post-hepatic Jaundice: Treatment involves relieving the obstruction. This is often achieved through endoscopic procedures (e.g., ERCP with sphincterotomy and stone extraction or stent placement) or surgery (e.g., cholecystectomy for gallstones, surgery to remove tumors or bypass obstructions).

Symptomatic Management:

Pruritus: Can be managed with medications like cholestyramine (a bile acid binder), rifampicin, naltrexone, or antihistamines.

Nutritional Support: May be necessary, especially if there is malabsorption of fat-soluble vitamins (due to lack of bile).

Pain Management: Analgesics as needed, avoiding NSAIDs in patients with liver disease.

Management of Complications: Addressing complications of liver disease (e.g., ascites, encephalopathy, bleeding).

We are a supportive platform dedicated to empowering student nurses and midwives through quality educational resources, career guidance, and a vibrant community. Join us to connect, learn, and grow in your healthcare journey

Quick Links

Our Courses

Legal / Policies

Get in Touch

(+256) 790 036 252

(+256) 748 324 644

Info@nursesonlinediscussion.com

Kampala ,Uganda

© 2025 Nurses online discussion. All Rights Reserved | Design & Developed by Opensigma