Central Nervous System

Subtopic:

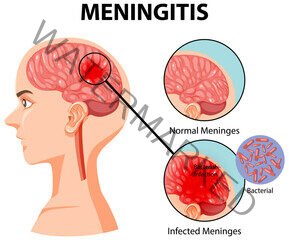

Meningitis

Meningitis is an inflammation of the meninges, the protective membranes that surround the brain and spinal cord.

This inflammation is typically caused by an infection, most commonly viral or bacterial, but can also be due to fungi, parasites, or non-infectious causes like certain medications or autoimmune diseases. Meningitis is a serious condition that requires prompt medical attention as it can lead to severe complications, including brain damage, hearing loss, learning disabilities, and even death.

Causes and Types of Meningitis

Meningitis can be caused by various pathogens or other factors. The type of pathogen causing the infection significantly impacts the severity and treatment.

Bacterial Meningitis: This is a medical emergency and is the most severe form. Bacteria that commonly cause meningitis include:

Streptococcus pneumoniae (Pneumococcus): A leading cause in adults and children.

Neisseria meningitidis (Meningococcus): Can cause epidemics, particularly in crowded settings.

Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib): Less common now due to vaccination.

Listeria monocytogenes: Can affect newborns, pregnant women, older adults, and immunocompromised individuals.

Group B Streptococcus: A common cause in newborns. Bacterial meningitis is life-threatening and requires immediate antibiotic treatment.

Viral Meningitis: This is the most common type and is usually less severe than bacterial meningitis. Enteroviruses are the most frequent cause, but other viruses like herpes simplex virus, varicella-zoster virus (chickenpox and shingles), mumps virus, and measles virus can also cause it. Viral meningitis often resolves on its own within 7-10 days, and treatment is usually supportive.

Fungal Meningitis: This is rare and typically occurs in individuals with weakened immune systems (e.g., those with HIV/AIDS, cancer, or on immunosuppressive medications). Cryptococcus neoformans is a common cause. Fungal meningitis is treated with long courses of antifungal medications.

Parasitic Meningitis: This is also rare and can be caused by various parasites. Naegleria fowleri, an amoeba found in warm freshwater, can cause a rare but devastating form of meningitis called primary amebic meningoencephalitis (PAM).

Non-Infectious Meningitis: Inflammation of the meninges can also occur due to non-infectious causes such as:

Certain cancers (carcinomatous meningitis).

Autoimmune diseases (e.g., lupus, sarcoidosis).

Certain medications.

Head injury or brain surgery.

Pathophysiology

Regardless of the cause, meningitis involves inflammation of the meninges. The process typically begins when a pathogen enters the bloodstream and travels to the central nervous system (CNS), or directly invades the meninges through trauma, surgery, or spread from a nearby infection (e.g., sinusitis, otitis media).

Once in the subarachnoid space (the space between the arachnoid mater and pia mater, which contains cerebrospinal fluid – CSF), the pathogens multiply and trigger an inflammatory response. This inflammation leads to:

Increased vascular permeability: Blood vessels in the meninges become leaky, allowing fluid, proteins, and inflammatory cells (like neutrophils in bacterial meningitis) to enter the subarachnoid space.

Accumulation of exudate: The buildup of inflammatory cells and fluid in the subarachnoid space.

Increased intracranial pressure (ICP): The inflammation and exudate can impede the flow and reabsorption of CSF, leading to a buildup of CSF and increased pressure within the skull. The inflamed meninges can also irritate the underlying brain tissue.

Cerebral edema: Swelling of the brain tissue can occur due to increased vascular permeability and impaired CSF drainage, further contributing to increased ICP.

Reduced cerebral blood flow: High ICP can compress blood vessels, reducing blood flow to the brain, potentially leading to ischemia and damage.

Damage to cranial nerves: The inflammation and pressure can affect the cranial nerves that pass through the meninges, leading to specific neurological deficits (e.g., hearing loss, visual problems).

In bacterial meningitis, the bacteria themselves can release toxins that damage brain cells and trigger a strong, potentially overwhelming, inflammatory response. This rapid and severe inflammation is why bacterial meningitis is so dangerous.

Clinical Manifestations

The signs and symptoms of meningitis can vary depending on the age of the patient, the type of pathogen, and the severity of the infection. However, there is a classic triad of symptoms often seen in bacterial meningitis in older children and adults:

Fever: Often high and sudden onset.

Severe Headache: Usually intense and persistent.

Stiff Neck (Nuchal Rigidity): Difficulty or inability to flex the neck forward. This is a hallmark sign of meningeal irritation.

Other common signs and symptoms include:

Photophobia: Sensitivity to light.

Phonophobia: Sensitivity to sound.

Altered Mental Status: Confusion, irritability, difficulty concentrating, drowsiness, lethargy, stupor, or coma.

Nausea and Vomiting: Often projectile.

Rash: A characteristic non-blanching petechial or purpuric rash can occur in meningococcal meningitis. This rash does not fade when pressed.

Seizures: Can occur due to irritation of the brain tissue.

Muscle or Joint Pain: Especially in meningococcal meningitis.

Lack of Appetite.

In Infants and Young Children:

Symptoms can be less specific and harder to recognize in infants. They may include:

Fever (or sometimes hypothermia).

Irritability or fussiness.

Drowsiness or difficulty waking up.

Poor feeding.

Bulging fontanelle (the soft spot on a baby’s head).

Stiff body or neck (though nuchal rigidity may be absent).

High-pitched crying.

Seizures.

Specific Signs of Meningeal Irritation:

Two classic signs assessed during physical examination that indicate meningeal irritation are:

Kernig’s Sign: With the patient lying supine, flex the hip to 90 degrees and then attempt to extend the knee. Kernig’s sign is positive if there is resistance and pain in the hamstring muscles and back.

Brudzinski’s Sign: With the patient lying supine, passively flex the patient’s neck forward towards the chest. Brudzinski’s sign is positive if this causes involuntary flexion of the hips and knees.

Diagnosis

Diagnosing meningitis requires a combination of clinical assessment and laboratory tests.

History and Physical Examination: Gathering information about symptoms, their onset, potential exposures, vaccination history, and performing a thorough neurological examination, including checking for signs of meningeal irritation.

Lumbar Puncture (Spinal Tap): This is the definitive diagnostic test. A small amount of CSF is collected from the lower back and sent to the laboratory for analysis. CSF analysis includes:

Cell Count and Differential: Elevated white blood cell count (especially neutrophils in bacterial meningitis, lymphocytes in viral meningitis).

Protein Level: Often elevated in meningitis.

Glucose Level: Typically decreased in bacterial meningitis (bacteria consume glucose). Normal in viral meningitis.

Gram Stain and Culture: To identify bacteria, if present.

PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction): Can detect viral or bacterial DNA/RNA.

Blood Tests:

Complete Blood Count (CBC): May show an elevated white blood cell count.

Blood Cultures: To identify bacteria in the bloodstream, as bacteremia can precede meningitis.

Inflammatory Markers: C-reactive protein (CRP) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) may be elevated.

Imaging Studies:

CT Scan or MRI of the Brain: May be performed before a lumbar puncture if there are signs of increased ICP, focal neurological deficits, or a history of head trauma or brain surgery, to rule out conditions like a brain abscess or mass that could make a lumbar puncture unsafe. Imaging can also show signs of complications like hydrocephalus or cerebral edema.

Management

Management of meningitis depends heavily on the cause. Prompt initiation of treatment is critical, especially for bacterial meningitis.

Bacterial Meningitis:

Immediate Antibiotics: Broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics are started as soon as bacterial meningitis is suspected, even before culture results are available. Antibiotics are chosen based on the likely pathogens for the patient’s age group and local epidemiology. Once the specific bacteria are identified and their antibiotic sensitivities are known, the antibiotics may be adjusted.

Corticosteroids: Dexamethasone is often given before or with the first dose of antibiotics in bacterial meningitis (especially in children with Hib meningitis and adults with pneumococcal meningitis) to reduce inflammation and prevent neurological complications like hearing loss.

Isolation: Patients with suspected or confirmed bacterial meningitis (especially meningococcal) are placed in respiratory isolation to prevent spread.

Management of Increased ICP: Elevate the head of the bed, maintain midline head position, avoid activities that increase ICP (e.g., coughing, straining). Osmotic diuretics (e.g., mannitol) may be used in severe cases.

Fluid and Electrolyte Management: Careful monitoring and management of fluid balance and electrolytes, as patients may develop syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone (SIADH) leading to hyponatremia.

Seizure Control: Anticonvulsant medications may be needed to treat or prevent seizures.

Fever Control: Antipyretics to reduce fever.

Management of Complications: Addressing complications such as hearing loss, cranial nerve palsies, hydrocephalus, or vascular complications.

Viral Meningitis:

Supportive Care: Treatment is primarily supportive. This includes rest, fluids, and medications for fever and headache (e.g., acetaminophen, ibuprofen).

Antiviral Medications: May be used if the cause is a specific treatable virus, such as herpes simplex virus or varicella-zoster virus.

Isolation: Usually not required unless the underlying viral infection warrants it.

Fungal Meningitis:

Antifungal Medications: Treated with long courses of intravenous antifungal drugs, such as amphotericin B, often in combination with other antifungals.

Non-Infectious Meningitis:

Treatment of the Underlying Cause: Management focuses on treating the condition causing the meningeal inflammation (e.g., immunosuppressants for autoimmune causes, chemotherapy for carcinomatous meningitis).

Nursing Management

Nursing care for patients with meningitis is critical and involves close monitoring, supportive care, and patient education.

Neurological Assessment: Frequent monitoring of neurological status, including level of consciousness (using Glasgow Coma Scale), vital signs, pupil response, motor and sensory function, and presence of meningeal irritation signs. Report any changes immediately.

Vital Sign Monitoring: Monitor temperature, pulse, respiration, and blood pressure frequently. Note any signs of increased ICP (e.g., widened pulse pressure, bradycardia, irregular respirations – Cushing’s triad).

Fluid and Electrolyte Monitoring: Accurate I&O, daily weight, monitor serum electrolyte levels. Assess for signs of fluid overload or dehydration.

Pain Management: Administer analgesics as prescribed for headache and muscle pain.

Fever Management: Administer antipyretics and use cooling measures as needed.

Seizure Precautions: Implement seizure precautions for patients at risk. If a seizure occurs, ensure patient safety and document the event.

Isolation Precautions: Implement appropriate isolation precautions based on the suspected or confirmed pathogen (e.g., droplet precautions for meningococcal meningitis).

Medication Administration: Administer antibiotics, antivirals, antifungals, corticosteroids, and other medications as prescribed. Monitor for side effects.

Comfort Measures: Provide a quiet, dark environment due to photophobia and phonophobia. Position the patient for comfort, often with the head of the bed elevated.

Skin Care: Assess for and manage any rash. Provide regular skin care, especially if the patient has altered mobility or consciousness.

Nutritional Support: Monitor nutritional intake. Patients may require IV fluids or tube feeding if they have difficulty swallowing or are unconscious.

Patient and Family Education: Educate about the disease, treatment plan, importance of completing the full course of antibiotics (if bacterial), potential complications, and follow-up care. For contagious types, educate about the need for isolation and prophylactic treatment for close contacts.

Emotional Support: Provide support to the patient and family, who may be experiencing significant anxiety and fear.

Get in Touch

(+256) 790 036 252

(+256) 748 324 644

Info@nursesonlinediscussion.com

Kampala ,Uganda

© 2025 Nurses online discussion. All Rights Reserved Design & Developed by Opensigma.co