Pain Management

Subtopic:

Pain Management in Palliative Care

The World Health Organization (WHO) emphasizes that being free from pain caused by cancer and conditions like HIV/AIDS is a fundamental human right. Effective pain management follows a thorough assessment.

Key Principles for Effective Pain Management

The WHO has established several core principles to guide pain management strategies:

By Mouth (Oral Route): Administer medication orally whenever feasible.

By the Clock (Regular Dosing): For persistent pain, medication should be given at regular intervals, typically around-the-clock (e.g., every 4 hours for oral morphine).

Administer analgesics at consistent times.

Ensure the next dose is given before the previous one wears off.

Adjust the dosage to achieve pain relief.

By the Ladder (WHO Analgesic Ladder): Utilize the WHO analgesic ladder as a framework for treatment, adjusting medication strength up or down the ladder as needed.

By the Patient (Individualized Approach): Dosage should be tailored to each patient’s individual needs, as pain experience varies.

The choice of pain medication should be appropriate for the specific type and intensity of pain, and a combination of drugs may be necessary.

Attention to Detail/Adjuvants (Addressing Additional Needs):

Regular laxatives are usually needed for patients on opioid pain medication to prevent constipation, except in cases of persistent diarrhea.

Antiemetics (anti-nausea medication) are commonly required when initiating morphine treatment, particularly in African populations.

Not all pain is responsive to opioids and the analgesic ladder approach.

Consider other pain types and treatments:

Bone pain: NSAIDs +/- opioids

Nerve compression: Steroids

Increased edema/ICP: Steroids

Inflammation: Steroids

Opioid-resistant pain

Muscle spasm/pain: Muscle relaxants

Neuropathic pain: Tricyclic antidepressants (e.g., amitriptyline) and anticonvulsants

Types of Pain Management

Non-pharmacological Pain Management

Physical: Incorporates physical methods like massage, exercise, physiotherapy, and surgical interventions in some cases.

Psychological: Focuses on strengthening the patient’s coping mechanisms through counseling techniques and relaxation exercises.

Social: Provides assistance to the patient in addressing social or cultural issues, accessing community resources, financial and legal aid, and other support systems.

Spiritual: Encompasses spiritual and religious support, including counseling and prayer.

Pharmacological Pain Management

Nociceptive Pain (Normal Pain) Management:

Adhere to WHO guidelines for pain management.

Favor the oral route of medication administration whenever possible.

Administer pain medication at fixed, scheduled intervals to prevent pain recurrence, giving the next dose before the previous one wears off.

Actively involve adults and children in their care, linking medication doses to their daily routines for better adherence.

Select pain medications based on the WHO analgesic ladder, which categorizes analgesics to treat mild, moderate, and severe pain.

WHO Analgesic Ladder

Developed by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 1996, the analgesic ladder serves as a structured method for controlling pain, especially in cancer care.

The ladder is structured into three distinct stages.

If a medication at the current stage fails to provide adequate relief, it is recommended to advance to a more potent analgesic from the subsequent stage of the ladder. Treatment should then escalate to this next step.

Effective pain management using this ladder involves a phased strategy. It allows for flexibility to adjust treatment intensity, moving both to stronger or weaker analgesics on the ladder as dictated by the patient’s pain levels and response to treatment.

The WHO Analgesic Ladder has a high success rate, effectively alleviating pain for approximately 90% of individuals with cancer.

WHO Analgesic Ladder: Stages of Treatment

Step 1: Mild Pain (Non-Opioid Analgesics)

Paracetamol (Acetaminophen):

Standard adult dosage: 500mg to 1g orally every 6 hours, not exceeding a daily limit of 4g.

Can be safely used alongside a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID).

Ibuprofen (NSAID):

Typical adult dosage: 400mg orally every 6 to 8 hours, with a maximum daily intake of 1.2g.

It is recommended to take ibuprofen with food and to avoid its use in patients with asthma if possible.

Effective in managing pain originating from bones and soft tissues.

Step 2: Moderate Pain (Weak Opioid Analgesics)

Codeine:

Standard adult dosage: 30-60mg orally every 4 hours, with a total daily dose ranging from 180 to 240mg.

Frequently used in combination with Step 1 analgesics for enhanced pain relief.

It is important to administer laxatives concurrently to prevent constipation, unless the patient is experiencing diarrhea.

Tramadol:

Typical adult dosage: 50-100mg orally every 4 to 6 hours.

Initiate treatment with a lower dose and increase as necessary, up to a maximum daily dose of 400mg.

Exercise caution when prescribing to individuals with epilepsy.

Step 3: Severe Pain (Strong Opioid Analgesics)

Morphine:

Considered the benchmark or “gold standard” opioid analgesic for severe pain.

There is no fixed maximum dose; the appropriate dose is the one that effectively manages pain without causing intolerable side effects. (In Uganda, a starting dose of 30mg over 24 hours is common).

Starting dosages are adjusted based on individual factors such as age, prior opioid use, and overall clinical status.

Typical starting dose range: 5-10mg orally every 4 hours, adjusted based on factors like age and previous experience with opiates.

Increase the dosage gradually as needed to achieve pain control.

For frail or elderly patients, it’s advisable to commence with a reduced dose (e.g., 2.5mg orally every 6-8 hours) due to potential renal function impairment.

Pharmacology of Morphine in the Analgesic Ladder

MORPHINE

Morphine is a frequently prescribed analgesic, often available in liquid formulations. It is prepared in varying strengths, indicated by color-coding: weak (green), with a concentration of 5mg/5ml; strong (red), at 50mg/5ml; and very strong (blue), at 100mg/5ml. Liquid morphine is versatile and widely employed for diverse pain management needs.

Mode of Action

Morphine’s pain-relieving effect is achieved by binding to opioid receptors in the brain and spinal cord. Specifically, morphine interacts with both mu and kappa opioid receptor sites, resulting in significant analgesia (pain relief).

It modulates pain signal transmission within the spinal cord and activates inhibitory pathways originating from the brain stem and basal ganglia, reducing pain perception.

Morphine also influences the limbic system and higher brain regions, thereby impacting the emotional component of pain experience.

Furthermore, morphine exerts effects on the gastrointestinal and respiratory systems, partly mediated by the autonomic nervous system and through direct interaction with opioid receptors located in peripheral tissues.

Indications of Morphine

Primary Use: Morphine is mainly indicated for managing moderate to severe pain conditions.

Acute Myocardial Infarction (Heart Attack): It is also valuable in treating acute heart attack situations to alleviate chest pain and lessen anxiety levels.

Symptomatic Relief: Morphine is employed for symptomatic relief of severe acute and chronic pain, especially when non-opioid analgesics have not provided sufficient pain relief.

Preanesthetic Medication: Morphine can be administered as part of pre-anesthesia protocols before surgical procedures.

Dyspnea Relief: It aids in alleviating shortness of breath associated with conditions like heart failure and pulmonary edema (fluid in the lungs).

Management of Myocardial Infarction (MI): Morphine is a therapeutic option in the acute management of chest pain related to myocardial infarction (MI).

Symptom Control: Morphine can be used to manage distressing symptoms such as diarrhea, cough, and dyspnea (difficult breathing) in certain clinical contexts.

Common Side Effects

Constipation: It is standard practice to prescribe laxatives alongside morphine treatment to counteract constipation, unless the patient is already experiencing diarrhea. For instance, Bisacodyl 5mg may be given at night, with the option to increase to 15mg if needed.

Nausea and Vomiting: Should nausea or vomiting occur, anti-emetic medications can be administered. Examples include Plasil 10mg every 8 hours or Haloperidol 0.5mg once daily.

Drowsiness: Some individuals may feel drowsy, particularly at the start of morphine therapy. If drowsiness persists beyond the initial three days, a reduction in the morphine dosage may be advisable.

Itching: Although not very common, itching (pruritus) can be a side effect of morphine. In such instances, lowering the morphine dose can often help reduce the itching sensation.

Contraindications

Acute or Severe Asthma: Morphine is generally not recommended for patients with acute or severe asthma because it carries a potential risk of worsening respiratory symptoms.

Gallbladder Disease: Morphine may either intensify pain related to gallbladder disease or mask the pain symptoms, particularly those associated with biliary tract spasms. Caution is advised when considering morphine use in these cases.

Gastrointestinal (GI) Obstruction: Morphine should be avoided in patients known to have, or suspected of having, gastrointestinal obstruction, as it could exacerbate the condition or lead to further complications.

Severe Hepatic Impairment: Morphine should be used with caution in patients who have severe liver impairment, as the body’s ability to process and eliminate the drug may be compromised.

Severe Renal Impairment: Morphine should also be used cautiously in patients with severe kidney impairment, as the removal of the drug from the body may be slowed down. This can potentially lead to drug accumulation and an elevated risk of adverse effects.

Caution in Specific Populations: Elderly patients and those who are debilitated or cachectic (severely weakened and wasting away) should typically be started on reduced doses of morphine.

Adverse Effects of Morphine

Dysphoria: Morphine has the potential to induce feelings of restlessness, depression, and anxiety in some individuals.

Hallucinations: Certain individuals might experience hallucinations as a side effect of morphine intake.

Nausea: Morphine can be a cause of nausea.

Constipation: Constipation is a frequently encountered side effect associated with morphine use.

Dizziness: Morphine can lead to dizziness.

Itching: Some people may experience itching as an adverse reaction.

Overdose: Taking too much morphine can result in severe respiratory depression or cardiac arrest, which are life-threatening conditions.

Tolerance: With prolonged use, tolerance can develop to the sedative, nausea-inducing, and euphoric effects of morphine, meaning higher doses may be needed to achieve the same effects over time.

Drug Interactions of Morphine

Central Nervous System (CNS) Depressants: Using morphine in combination with other CNS depressants – such as alcohol, other opioid medications, general anesthetics, sedatives, and certain antidepressants like monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) and tricyclic antidepressants – can amplify the effects of opioids. This heightened effect significantly elevates the risk of severe respiratory depression and other potentially life-threatening complications.

Monoamine Oxidase (MAO) Inhibitors: Combining morphine with MAO inhibitors, a class of antidepressant medication, may lead to intensified opioid effects and increases the risk of serotonin syndrome. Serotonin syndrome is a serious and potentially fatal condition characterized by a cluster of symptoms including agitation, hallucinations, rapid heartbeat, elevated body temperature, and fluctuations in blood pressure.

Tricyclic Antidepressants: The concurrent use of morphine with tricyclic antidepressants may enhance the pain-relieving effects of morphine. However, this combination also increases the potential for adverse effects, notably sedation and respiratory depression.

Black Box Warning:

Epidural Morphine Administration: When morphine is administered as an epidural injection, patients require close monitoring in a fully equipped medical setting with trained staff for a minimum of 24 hours due to the risk of serious adverse reactions.

Abuse Potential of Extended-Release Morphine: Extended-release morphine tablets carry a risk of misuse and abuse that is similar to other opioid analgesics.

Controlled Substance Classification: Morphine is classified as a Schedule II controlled substance. It must be dispensed and used strictly according to the provided instructions. Tablets or capsules must be swallowed whole and should not be broken, chewed, dissolved, or crushed to avoid rapid release and potential overdose.

Avoid Alcohol Consumption: Alcohol intake should be strictly avoided while using morphine products due to the increased risk of adverse effects, particularly respiratory depression.

Risk of Fatal Respiratory Depression: Failure to adhere to these warnings and precautions can lead to severe and potentially fatal respiratory depression.

Treatment of Morphine Overdose

Naloxone Administration: Naloxone is an opioid antagonist that works by blocking opioid receptors, effectively reversing the effects of morphine overdose. Typically administered intravenously (IV), it rapidly acts to restore normal breathing and consciousness. The number of naloxone doses needed can vary, depending on how severe the overdose is.

Activated Charcoal: Activated charcoal may be given orally or via a nasogastric tube. It functions to prevent further absorption of morphine from the gastrointestinal tract by binding to the drug. This action reduces the amount of drug available to circulate in the body.

Laxative Use: A laxative may be given to encourage bowel movements, helping to eliminate morphine from the digestive system more quickly. This action helps to reduce drug absorption and improve overall removal from the body.

Narcotic Antagonists: In addition to naloxone, other opioid antagonists, such as naltrexone, can be used to counteract the effects of morphine overdose. These medications compete with morphine for opioid receptors and are useful in reversing respiratory depression and other opioid-related symptoms.

About Naloxone.

Actions and Uses of Naloxone

Naloxone functions as a pure opioid antagonist.

It works by blocking both mu and kappa opioid receptors.

Used for:

Reversing opioid effects in emergency situations where opioid overdose is suspected.

Treatment of postoperative opioid-induced respiratory depression.

As supportive treatment to reverse low blood pressure (hypotension) caused by septic shock.

II. Administration Alerts

Administer if the respiratory rate is at or below 10 breaths per minute.

Ensure that resuscitation equipment is readily available before administration.

Classified as Pregnancy category B.

III. Adverse Effects of Naloxone

Exhibits minimal toxicity.

Reversal of opioid effects can lead to:

Rapid return of pain.

Elevated blood pressure.

Tremors or shaking.

Hyperventilation (rapid and deep breathing).

Nausea and vomiting.

Drowsiness.

IV. Contraindications

Naloxone is not appropriate for reversing respiratory depression caused by non-opioid medications.

About Dependence

I. Opioid Dependence

Dependence is defined as a condition where a patient feels unable to function normally without the presence of the drug.

Psychological dependence (addiction):

Characterized by experiencing strong cravings for the drug and engaging in compulsive drug-seeking behaviors.

Physiological dependence:

If the medication is suddenly stopped, patients may experience withdrawal symptoms.

The likelihood of physiological dependence is reduced when using lower doses and in patients with shorter life expectancies, such as those with advanced cancer.

Therapeutic dependence:

Therapeutic dependence emerges when the primary source of pain is not addressed, resulting in sustained reliance on morphine. Conversely, upon resolution of the pain’s origin, morphine dosage necessitates appropriate adjustment.

High Risk of Dependence: Opioid medications present a substantial risk for the development of dependence.

Rapid Tolerance Development: Tolerance to opioids can develop swiftly, necessitating increased dosages and more frequent administration to achieve the intended effect.

Physical Dependence with Increased Dosage: Physical dependence is more likely to occur with higher and more frequent opioid dosages.

Withdrawal Upon Discontinuation: Cessation of opioid use can lead to uncomfortable withdrawal symptoms.

Psychological Dependence Persistence: Psychological dependence and strong cravings can endure even after physical dependence is overcome.

Importance of Support Groups: Support groups are crucial for preventing relapse.

II. Treatment Options for Opioid Dependence

Methadone Maintenance

Transition from Illicit Drug Use: Involves switching from illegal intravenous or inhaled drugs to oral methadone administration.

Non-Euphoric Functionality: Methadone is formulated to minimize euphoric effects, enabling patients to maintain normal daily activities.

Continued Use for Withdrawal Prevention: Methadone maintenance necessitates ongoing drug use to effectively prevent withdrawal symptoms.

Comprehensive Benefits: Offers physical, emotional, and legal advantages in comparison to illicit drug use.

Buprenorphine Therapy

Administration Routes: Can be administered sublingually (under the tongue) or transdermally (through the skin).

Early Use in Therapy: Utilized early in opioid use disorder treatment to mitigate withdrawal symptoms.

Suboxone Formulation (Buprenorphine/Naloxone): Suboxone, a combination medication, is employed for the maintenance treatment of opioid addiction.

Adjuvant Medication

Adjuvant medications are drugs primarily designed for other conditions but can effectively alleviate pain in specific situations. They can be utilized independently or alongside other analgesics within the analgesic ladder framework. Adjuvant medications are particularly important for managing pain that does not respond adequately to opioid treatments.

Examples of adjuvant medications include:

Antidepressants (e.g., Amitriptyline):

Indicated for treating pain originating from nerve damage.

Cancer-related pain may also necessitate the integration of antidepressants.

The full therapeutic effects might take several weeks to manifest, although initial benefits may be observed within a week.

Commonly used antidepressants include Amitriptyline (typically 12.5–50mg at night) and Imipramine (10–50mg at night).

Administered at night to potentially promote sleep.

Potential side effects encompass drowsiness, dry mouth, and urinary retention.

Anticonvulsants (e.g., Phenytoin, Carbamazepine):

Used in the management of neuropathic pain.

Can be employed as an alternative to or in combination with antidepressants or opioid analgesics.

Their mechanism of action involves the blockade of sodium channels and enhancement of GABA-mediated synaptic inhibition within the nervous system.

Examples of anticonvulsants include Phenytoin, Sodium valproate, Clonazepam, and Gabapentin.

Corticosteroids (e.g., Dexamethasone):

Exhibit diverse applications in palliative care settings.

Beneficial for pain induced by tumor pressure and inflammation processes.

Ideally used as a short-term intervention due to possible side effects associated with prolonged use.

Indicated for conditions like nerve compression, superior vena caval obstruction, elevated intracranial pressure (headache), and bone pain.

Possible side effects can include gastric irritation, oral candidiasis (thrush), fluid retention (ankle swelling), proximal myopathy (muscle weakness near the torso), steroid-induced diabetes mellitus, and psychosis.

Smooth Muscle Relaxants (e.g., Buscopan, Diazepam):

Employed for specific pain types, such as biliary colic, bowel obstruction, ureteric colic, contractures, or spastic paraparesis.

Illustrative examples are Hyoscine butylbromide (Buscopan), Oxybutynin, Diazepam, and Clonazepam.

Drowsiness is a potential side effect.

Other interventions in pain management

Antibiotics for infected wounds.

Use of frangipani petals for post-herpetic neuralgia (neuropathic pain following shingles).

Capsaicin cream for neuropathic pain conditions.

Massage therapy and reflexology techniques.

Myths surrounding the use of opioids:

Myth: Morphine is only for individuals on the verge of death.

Reality: The intensity of discomfort, not the progression of a terminal illness, dictates the necessity for pain relief medication.

Myth: Morphine prescriptions are solely based on pain scores, implying long-term dependence.

Reality: Morphine dosage is personalized to the patient’s pain level, and some individuals might only require it for a limited period.

Myth: Active living is impossible when managing pain with morphine.

Reality: Effective pain management with morphine enables patients to maintain an active lifestyle and enhance their overall well-being.

Healthcare providers do an adequate job of providing pain control:

Challenges in Optimal Pain Management: Obstacles exist for healthcare professionals in consistently achieving excellent pain control for patients.

Potential Doctor Oversights: Physicians might sometimes prioritize disease-focused treatment, potentially overlooking the comprehensive assessment and management of patient pain.

Risk of Nurse Under-Dosing: Nurses may, at times, administer opioid doses lower than what is prescribed, which can lead to inadequate pain relief, especially in acute pain scenarios.

Pain medications always lead to addiction:

Appropriate Opioid Use & Addiction Risk: When opioids are used correctly for short-term management of acute pain, the risk of developing addiction is low.

Negative Impact of Prescribing Reluctance: Hesitancy to prescribe opioids due to concerns about addiction can unjustly deprive patients of effective pain relief.

People on morphine die sooner because of respiratory depression:

Low Risk of Respiratory Depression: Respiratory depression is uncommon, particularly when initiating oral morphine with careful and gradual dose adjustments (titration).

Safe Relief of Dyspnea with Low Dose Morphine: Small doses of morphine can be safely and effectively used to alleviate shortness of breath (dyspnea) in patients with conditions like COPD or lung cancer.

Pain medications always cause heavy sedation:

Initial Sedation in Chronic Pain: Some initial drowsiness might occur, especially in individuals experiencing chronic pain-induced sleep deprivation.

Return to Alertness with Appropriate Dosing: With correctly adjusted opioid dosages, patients are generally able to regain their normal level of mental clarity and orientation.

People should not take morphine before their pain is severe, lest it lose its effect:

No Upper Limit & Dose Escalation: There is no fixed maximum dosage for morphine; the dose can be increased as needed to manage escalating pain.

Early Use & Sustained Effectiveness: Starting opioids early in the course of pain management does not reduce their effectiveness if needed later, even in terminal conditions.

Some kinds of pain cannot be relieved:

Variable Medication Effects & Combination Therapy: Different pain medications have diverse mechanisms and effects, often requiring a combination approach to effectively manage complex pain.

Importance of Thorough Pain Assessment: Detailed pain assessment is crucial for healthcare providers to develop and prescribe the most appropriate pain management plan for effective relief.

Effective pain management can be achieved on an ‘as needed’ basis:

Prophylactic Administration for Optimal Control: Regular, around-the-clock administration of pain medication is often necessary to maintain consistent and effective pain control.

Benefits of Scheduled Dosing: Administering opioids on a scheduled basis can help minimize side effects and provide a more stable and continuous level of pain relief.

Opioid analgesics should be avoided in older patients:

Elderly Patients & Need for Strong Opioids: Older individuals with chronic moderate to severe pain conditions may still require and benefit from strong opioid medications.

Dosing Caution in Older Adults: Careful consideration and adjustments are needed when determining dosage and titration in elderly patients due to age-related changes in drug processing within the body (pharmacokinetic and physiological changes).

Other myths about managing pain:

Morphine and Hastening Death: Morphine does not accelerate death in terminally ill patients.

Injectable Morphine: Injectable morphine is not necessarily superior in effectiveness compared to other routes of administration.

Withholding Strong Analgesics: Potent pain relievers should not be withheld until death is imminent; they should be used when needed for pain relief.

Pain During Sleep: Patients can still experience pain even while sleeping.

Pain and Distraction: Pain can persist even when patients are engaged in activities like watching television or laughing.

Pain Experience in Children: Infants and children experience pain in ways comparable to adults.

Continuous Dose Increase: The dosage of pain medications does not always require continuous escalation.

Vital Signs as Pain Indicators: Vital signs alone are not dependable indicators of pain intensity in patients.

Myths and Fears about Morphine:

Myths:

Tolerance (Myth):

Misconception: Some patients and even healthcare providers believe that increasing morphine dosage to manage pain signals drug tolerance.

Reality: In palliative care, the effective morphine dose is simply the amount required to adequately control pain for each individual patient.

Dosage Increase and Addiction: The necessity for a higher morphine dose does not automatically indicate the patient is developing an addiction.

Physical dependence (Myth):

Withdrawal upon Discontinuation: Abruptly stopping opioid use typically leads to withdrawal symptoms.

Gradual Withdrawal: Gradual withdrawal over a period of 2-3 days can effectively minimize these symptoms.

Dependence vs. Addiction: This physical response is not indicative of addiction; it’s a normal physiological adaptation to the medication.

Addiction (Psychological dependence) (Myth):

Rarity of Addiction: Addiction to morphine when used for medical purposes is very uncommon and primarily associated with non-medical or recreational opioid use.

Infrequent in Medical Settings: Addiction in patients using morphine for pain management is not a frequent concern in medical practice.

Cognitive impairment (Myth):

Initial Effects: When morphine therapy is started, some initial sedation and temporary attention deficits, potentially including reduced short-term memory, may occur.

Transient Nature: These cognitive effects are generally transient and tend to resolve within three to five days.

Not Addiction Related: These cognitive changes are not a sign of addiction.

Lethality (Myth):

Safe Prescribing: Morphine, when prescribed appropriately with gradual dose adjustments guided by patient needs, does not cause death.

Overdose Management: In the rare event of an overdose, Naloxone is available and can effectively reverse the effects and manage the situation.

Fears:

A last resort before death? (Fear):

Misconception: Some people fear that morphine is exclusively prescribed as a final option when a patient is nearing death.

Reality of Use: In actuality, morphine is utilized to alleviate pain at various stages of illness, not just exclusively in end-of-life care.

Hastening death (Fear):

Fear of Speeding Dying Process: There’s a fear that morphine administration might accelerate the dying process.

Appropriate Use and Death Timing: When used correctly and for its intended purpose, morphine does not influence or hasten the timing of death.

Cause of Death in Severe Illness: Patients who are severely ill pass away due to the progression of their underlying condition (like advanced cancer or AIDS), not as a direct consequence of morphine.

Function Improvement: Morphine aids in pain relief, consequently allowing patients to maintain better functionality and quality of life for their remaining time.

Morphine is reserved until the end (Fear):

Misunderstanding about Timing: Some individuals mistakenly believe that morphine should only be considered as a last resort, very late in the course of illness.

Early Use Benefits: They fear that if morphine is started early in an illness, it may become ineffective later when pain potentially intensifies.

Versatile Use: However, morphine can be safely and effectively used at various stages of illness to provide consistent pain relief.

Respiratory distress (Fear):

Breathing Problem Concerns: Some people worry that morphine can induce breathing difficulties or respiratory problems, particularly if the person already has a pre-existing lung condition.

Overdose and Breathing Issues: Breathing difficulties can occur primarily as a result of morphine overdose.

Mitigation Strategies: Initiating treatment with low doses and gradually increasing the dosage as needed can significantly help in avoiding this issue.

Cough and Breathlessness Relief: Morphine can actually be employed to alleviate respiratory distress caused by severe cough or breathlessness in certain conditions.

The elderly should not be given morphine (Fear):

Response in Elderly Patients: Elderly individuals experiencing cancer-related pain demonstrate a pain relief response to morphine that is comparable to younger patients.

Increased Susceptibility to Side Effects: However, older adults might exhibit a higher likelihood of experiencing side effects from morphine.

Dosage Recommendations for Elderly: It is advisable to use smaller initial doses and implement more gradual dose increases when prescribing morphine to elderly patients.

Injection morphine is better than oral morphine (Fear):

Oral Absorption of Morphine: Morphine is effectively absorbed into the body when administered orally.

Cost-Effectiveness of Oral Liquid Morphine: Oral morphine in liquid form is a more economical option when compared to tablets or injectable formulations.

Limited Use of Injection Morphine: Injection morphine should be reserved for situations where oral administration is not feasible, such as in cases of severe vomiting that prevents oral intake.

Laws governing narcotics

International Regulation:

Global Conventions: Opioid medications are governed by the 1961 international treaty, with updates from the 1972 protocol.

Uganda’s Commitment: Uganda is a signatory to this international agreement, aiming to balance ensuring opioid availability for legitimate medical and scientific purposes with preventing misuse.

Regulated Aspects: The following stages in the lifecycle of narcotics are controlled under enacted laws:

Cultivation: Production of narcotic plants.

Manufacturing: Creation of narcotic substances.

Distribution: Supplying and dispensing narcotics.

Handler Registration: Official recording of all individuals and entities authorized to manage narcotics.

International Oversight: An international body monitors countries’ adherence to the stipulations of the convention.

Government Estimation & Board Confirmation: The national government projects the required annual quantities of opioids, which must be validated by the international regulatory board before production or import can occur.

Mandatory Reporting: Regular quarterly reports detailing imported, manufactured, and distributed opioids are compulsory, necessitating precise record-keeping practices.

Regulatory Communication: Official communication regarding narcotic regulations is managed through the Ministry of Health (MOH) and the National Drug Authority (NDA), with the NDA responsible for overseeing drug handling regulations.

Restricted or Class A Drugs:

Class A Drug Category: Class A drugs encompass opioids such as morphine and pethidine, among others with high potential for misuse and harm.

Stringent Procedures: Specific operational protocols, secure storage conditions, and detailed records are mandated to prevent the unauthorized diversion of these substances.

Record Retention: Records pertaining to Class A drugs must be maintained for a minimum of two years for audit and inspection purposes.

Reporting Loss: Any loss of Class A drugs must be formally reported to the Chief Inspector of Drugs (within the NDA) within a strict timeframe of seven days from discovery.

Expired, Rejected, or Returned Class A Drugs:

Return of Unused Drugs: Any unused portions of Class A drugs should be returned to the prescribing healthcare provider or dispensing pharmacy.

Return of Expired/Rejected Drugs: Expired or rejected Class A drugs are to be returned to the designated pharmacy in charge, who is then responsible for notifying and coordinating with the drug inspector for proper disposal.

Pharmacy-Led Destruction: Expired drugs must be destroyed by the pharmacy in charge, with the destruction process witnessed and verified by the drug inspector, adhering to World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines for safe disposal.

Documentation of Destruction: Comprehensive details about the quantity of drugs destroyed and the rationale for destruction must be meticulously documented and entered into the official Class A drug register.

Importation of Class A Drugs:

Import License Requirement: Manufacturing and wholesale activities involving Class A drugs necessitate possessing an annual import license issued by the relevant authority.

Authorized Importers: Currently, only the National Medical Stores (a governmental entity) and Joint Medical Stores (a non-governmental organization) are officially permitted to import narcotics into the country.

Access for Private Entities: Private retail pharmacies and hospitals can legally obtain narcotics by sourcing them through these officially licensed importing agencies.

Storage:

Separate Storage for Morphine Types: Powdered morphine (raw material) and finished morphine products must be stored in physically separate, secure, and immovable storage units or cupboards.

Double-Locked Security: The designated storage cupboard for narcotics must be double-locked and access strictly restricted to authorized personnel, preventing public access.

Key Control: The key to the narcotics cupboard must be securely held and managed exclusively by the designated pharmacist or dispensing personnel.

Disposal:

WI-TO Guidelines: Drug disposal procedures must strictly adhere to the WI-TO (Waste Inventory – Tracking and Operations) guidelines established by the National Drug Authority (NDA) to ensure safe and compliant waste management.

Destruction Recording: Detailed information regarding the quantity of drugs subjected to disposal and the specific reason for their destruction must be carefully recorded in the Class A drug register for accountability and audit trails.

Transport:

Licensing and Authorization: All entities and individuals engaged in the narcotics distribution network are mandated to possess appropriate licenses and official authorization from the regulatory bodies. This ensures accountability and traceability throughout the supply chain.

Anti-Narcotics Enforcement: A specialized anti-narcotic drug enforcement unit is in place to actively prevent narcotics from being diverted into illegal channels and the hands of drug trafficking organizations.

Prescription:

Authorized Prescribers: Only healthcare professionals registered and authorized under the national regulations, such as medical doctors, dentists, veterinary practitioners, specialized palliative care nurses, clinical officers, and registered midwives, are legally permitted to prescribe Class A controlled drugs. This restriction ensures responsible and medically justified use.

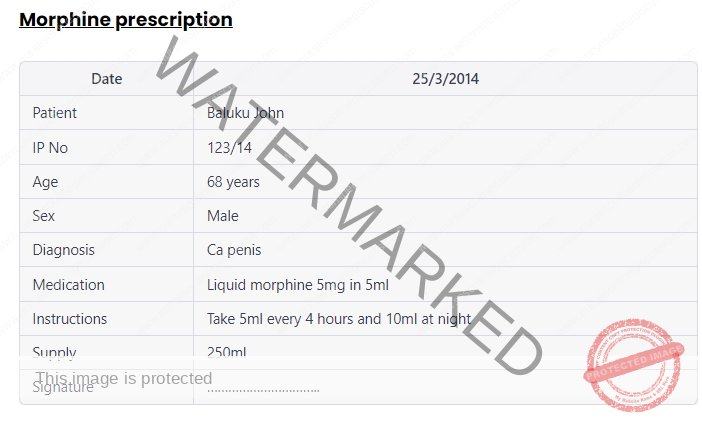

Legal Prescription Documentation: Prescription forms for Class A drugs are considered legal documents and must be meticulously completed with all mandatory information to ensure legality, patient safety, and proper dispensing.

Prescription Validity and Supply Limits: Prescriptions for Class A drugs are time-limited, typically valid for 14 days from the date of issue. Furthermore, the dispensed quantity must not exceed a one-month supply to prevent stockpiling and potential misuse. Duplicate copies of prescriptions are a standard requirement for record-keeping and audit purposes.

Prescription Requirements:

For a prescription of Class A drugs to be valid and legally compliant, it must contain the following essential details:

Patient Identification: Full name, age, sex, and complete residential address of the patient.

Dosage in Words and Numerals: The total prescribed dose of the drug, clearly stated both in words and numerical figures to avoid ambiguity.

Specific Drug Formulation: The precise form of the drug to be dispensed (e.g., tablets, injections, oral solution).

Strength Specification: Where applicable, the exact strength of the medication must be indicated (e.g., 5mg/5ml or 50mg/5ml for oral morphine), ensuring correct dispensing and dosage.

Penalties:

Consequences of Unlawful Possession: The unauthorized possession of classified controlled drugs (referring to Class A narcotics) is a serious offense that can result in significant legal penalties:

Financial Fine: A substantial fine, not exceeding 2 million Ugandan shillings, may be imposed.

Imprisonment: A term of imprisonment, for a duration not exceeding 2 years, may be enforced.

Combined Penalties: The legal system reserves the right to apply both financial fines and imprisonment concurrently, depending on the severity and circumstances of the offense.

We are a supportive platform dedicated to empowering student nurses and midwives through quality educational resources, career guidance, and a vibrant community. Join us to connect, learn, and grow in your healthcare journey

Quick Links

Our Courses

Legal / Policies

Get in Touch

(+256) 790 036 252

(+256) 748 324 644

Info@nursesonlinediscussion.com

Kampala ,Uganda

© 2025 Nurses online discussion. All Rights Reserved | Design & Developed by Opensigma