Medical Nursing (III)

Subtopic:

Bursitis

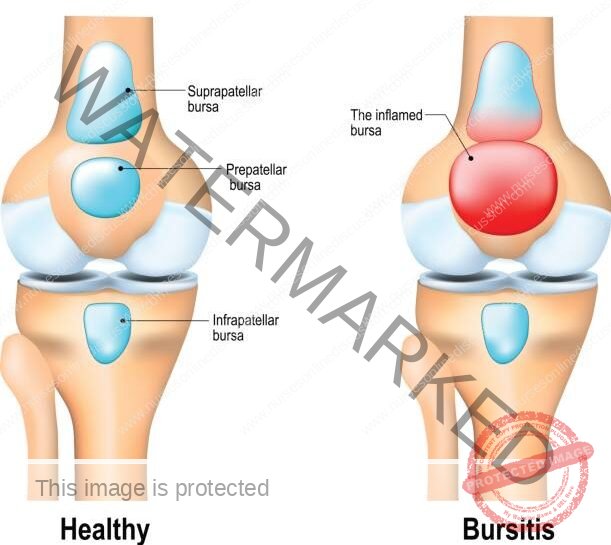

Bursitis is an inflammatory condition affecting a bursa. A bursa is a small, sac-like structure filled with fluid that acts as a natural cushion, reducing friction between bones and surrounding tissues like muscles, skin, or tendons.

Bursitis can also be described as a painful medical issue characterized by the inflammation of bursae, which are typically located around larger joints.

Bursae are essentially pouches filled with fluid that serve as protective pads between bones, tendons, joints, and muscles. When these sacs become irritated and inflamed, the condition is known as bursitis.

The human body contains over 150 bursae. Their role is to provide cushioning and lubrication at points where bones, tendons, and muscles move close to each other near joints.

The inner lining of bursae is composed of synovial cells. These cells produce a lubricating fluid that minimizes friction between tissues, allowing our joints to move smoothly and effortlessly.

Causes of Bursitis

Bursitis frequently arises from injuries sustained during sports or from movements that are repeated over and over. However, it can also be triggered by:

Autoimmune disorders: Conditions where the body’s immune system mistakenly attacks its own tissues.

Crystal deposition: The build-up of crystals in the joints, as seen in conditions like gout (uric acid crystals) and pseudogout (calcium pyrophosphate crystals).

Infectious diseases: Illnesses caused by bacteria, viruses, or fungi that can sometimes affect the bursae.

Traumatic events: Sudden impacts or injuries to a joint area.

Hemorrhagic disorders: Conditions affecting blood clotting that can lead to bleeding into the bursa.

Overuse: Excessive or repetitive use of a joint can place undue stress on the bursa. This can happen with repeated motions or due to an abnormal bone structure.

Stress on soft tissues: Unusual pressure on tissues around a joint caused by misalignment or poor positioning of the joint or bone.

Certain types of arthritis and related conditions: Inflammatory conditions like rheumatoid arthritis, degenerative conditions like osteoarthritis, or metabolic conditions like gout.

Metabolic conditions such as diabetes: While not a direct cause, diabetes can increase the risk of some types of bursitis.

Septic bursitis: This can occur when bacteria enter the bursa through a break in the skin, often following repetitive minor injuries.

Pathophysiology of Bursitis

Repeated irritation within a bursa leads to local blood vessel widening (vasodilatation) and increased leakiness of these vessels (vascular permeability). This triggers the body’s inflammatory response. Research suggests that this process might involve signaling molecules called cytokines, enzymes known as metalloproteases, and cyclooxygenases (which are involved in the production of inflammatory mediators).

Trauma or infection sets off inflammation within the bursa. This inflammation causes the synovial cells lining the bursa to multiply and increase the production of collagen (a structural protein) and fluid. The capillary membranes in the bursa become more permeable, allowing fluid rich in protein to enter. Over time, the normal lining of the bursa may be replaced by granulation tissue (new connective tissue) which then matures into fibrous tissue (scar-like tissue). The bursa then becomes filled with fluid, which often contains fibrin (a protein involved in blood clotting), and in some cases, the fluid can be bloody (hemorrhagic).

Types of Bursitis, with Signs and Symptoms

(a) According to duration.

Acute Bursitis: (0 months to 3 months) During the initial, acute stage of bursitis, localized inflammation develops within the bursa. The synovial fluid inside thickens, and movement around the affected area becomes painful.

Chronic Bursitis: (3 months and above): Prolonged inflammation leads to persistent pain. This can weaken the ligaments and tendons that lie over the bursa, potentially leading to their eventual tearing or rupture. Due to these potential complications, bursitis and tendinitis (inflammation of a tendon) frequently occur together.

(b) According to presence of infection.

Septic Bursitis: Septic (or infectious) bursitis arises when an infection invades the bursa. This can happen through direct introduction of bacteria (often affecting bursae close to the skin’s surface) or through the bloodstream or direct spread from another infected site (more common in deeper bursae). Septic bursitis can present suddenly (acute), be less intense but longer-lasting (subacute), or keep recurring (chronic). Fluid drawn from an infected bursa typically shows:

A high white blood cell count (WBC) greater than 100,000 cells per microliter, with a majority of these cells being neutrophils (a type of immune cell).

Elevated levels of protein and lactate.

A positive result on a culture test (indicating the presence of bacteria) and a positive Gram stain (a test used to identify the type of bacteria).

Aseptic Bursitis: This is a non-infectious form of bursitis caused by inflammation resulting from localized injury to soft tissues or strain. Fluid from an aseptically inflamed bursa typically shows:

A white blood cell count (WBC) ranging from 2,000 to 100,000 cells per microliter.

Negative results on culture and Gram stain tests, confirming the absence of bacterial infection.

(c) According to Anatomy/Affected body part.

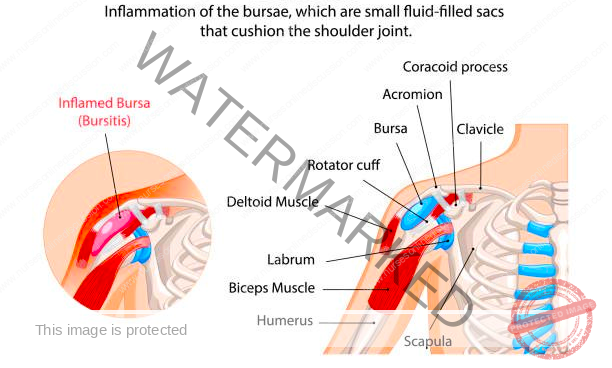

Subacromial bursitis:

Subacromial bursitis is a frequent cause of pain in the shoulder. It occurs due to inflammation of the subacromial bursa, which is situated beneath the acromion, a bony projection on the shoulder blade. This type of bursitis is commonly triggered by repetitive overhead movements, such as throwing a ball or painting, or by a direct injury to the shoulder.

Mid-shoulder pain early in the course of bursitis: In the beginning stages of subacromial bursitis, pain is often felt in the middle of the shoulder.

which gradually increases over time: This pain tends to worsen as the inflammation progresses.

eventually pain may be felt even at rest: As the bursitis becomes more severe, the pain can be present even when the shoulder is not being used.

Pain after repetitive activity such as painting, throwing a ball, or playing tennis: Activities that involve repeated overhead motions can aggravate subacromial bursitis and cause pain.

Pain worsens at night: Many individuals with subacromial bursitis find that their shoulder pain is more intense during the night, often making it difficult to sleep comfortably.

Popping sensation with shoulder movements: Some people may experience a clicking or popping feeling in their shoulder as they move it.

2. Olecranon bursitis

The olecranon bursa is a fluid-filled sac lined with a synovial membrane. It is located directly behind the olecranon, which is the bony point of the elbow.

The bursa’s function is to allow the bony tip of the elbow (olecranon) to move easily against the skin and tissues covering it when the elbow is bent (flexion) and straightened (extension). It acts as a cushion to reduce friction during these movements.

Painful or painless focal swelling at the posterior elbow

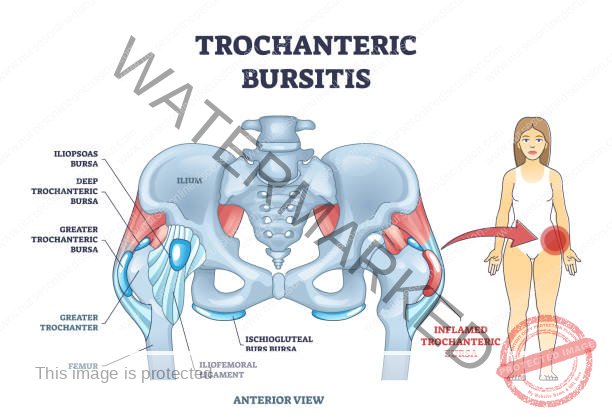

3. Trochanteric bursitis

Trochanteric bursitis is inflammation (swelling) of the bursa at the outside (lateral) point of the hip known

as the greater trochanter. When this bursa becomes irritated or inflamed, it causes pain in the hip. This is a

common cause of hip pain

Pain in the lateral side of the hip with walking, running, or stair-climbing

Weakness of the lower extremities

Pain with active and passive motion.

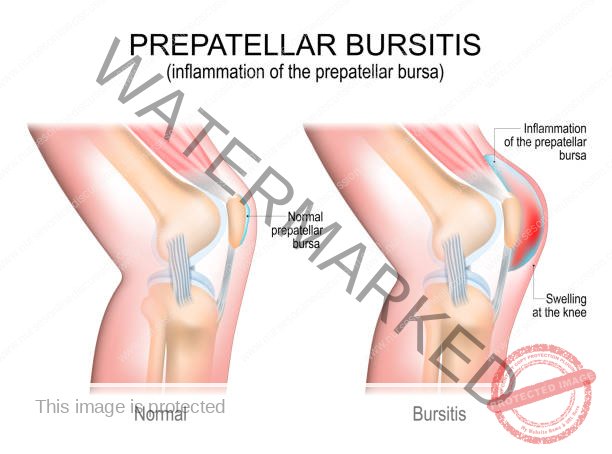

4. Prepatellar bursitis

Prepatellar bursitis is an inflammation of the bursa in the front of the kneecap (patella). It occurs when the

bursa becomes irritated and produces too much fluid, which causes it to swell and put pressure on the adjacent

parts of the knee.

Reduced range of motion at the knee

Focal swelling, pain, and redness

Difficulty kneeling and walking.

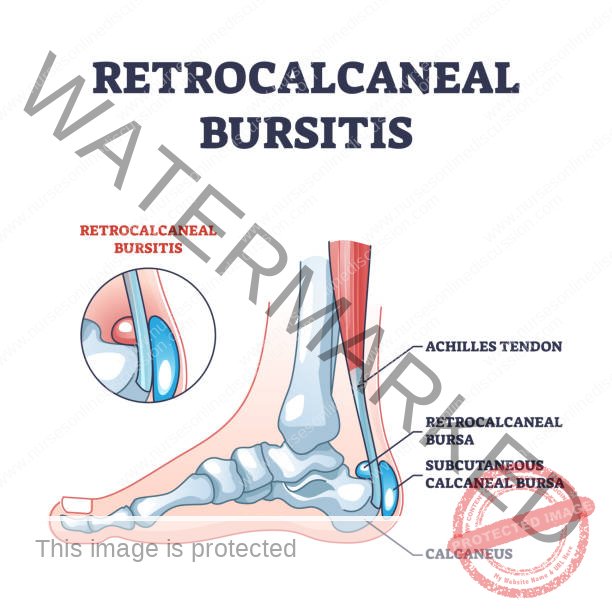

5. Retrocalcaneal bursitis

Retrocalcaneal bursitis (also known as ankle bursitis or Achilles tendon bursitis) is a condition in which the

retrocalcaneal bursa, a small cushioning sac between the heel bone and the Achilles tendon, becomes

inflamed.

Retrocalcaneal bursitis

Swelling at the back of heel

Pain at the back of the heel, especially when running uphill

Pain while standing on tiptoes

Diagnosis and Investigations

History and symptoms: The diagnostic process begins with gathering information about the patient’s medical history and the specific symptoms they are experiencing.

Physical examination: A thorough physical evaluation is performed to assess the affected area, checking for tenderness, swelling, range of motion, and any signs of inflammation.

Lab tests: Generally, routine blood tests are not helpful in diagnosing typical bursitis. However, in cases of suspected septic bursitis, laboratory markers such as the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP), and white blood cell count may be elevated, indicating infection.

X-ray: While X-rays can’t directly show bursitis, they can be used to rule out other conditions. X-rays of the affected joint are typically ordered when there’s a history of significant injury. A plain X-ray can help identify fractures or dislocations that might be contributing to the pain.

CT Scan: Computed tomography (CT) scans are usually reserved for patients whose bursitis doesn’t improve with initial treatment. On a CT scan, superficial bursitis may appear as a fluid-filled area within the tissues just under the skin. Importantly, CT scans can also help detect the presence of any foreign objects within the bursa.

Ultrasound Scan: Ultrasound is a valuable tool for confirming a diagnosis of bursitis. On an ultrasound image, bursitis can be characterized by the bursa appearing distended (swollen) with fluid inside (which may appear as a darker or less dense area – hypoechoic or anechoic). The ultrasound can also reveal thickening of the bursal wall (synovial proliferation), calcium deposits, and, in some cases, rheumatoid nodules.

Management and Treatment of Bursitis

Aims

To reduce the inflammation and pain.

To identify and treat the cause of the bursitis.

To prevent complications from developing.

Nursing Management

For most bursitis cases, the initial approach focuses on conservative methods to decrease inflammation and pain.

Conservative treatment strategies aim to manage pain and inflammation. A helpful mnemonic for remembering these strategies is PRICEMM:

Protect: Shield the affected area using padding, braces, or by modifying activities.

Rest: Avoid activities that make the pain worse.

Ice: Applying cold therapy can help reduce pain and swelling.

Compression: Using elastic bandages can provide support and reduce pain, particularly useful for olecranon bursitis (elbow bursitis).

Elevation: Raising the injured limb above heart level can help minimize swelling.

Modalities: Techniques like electrical stimulation, ultrasound therapy, or phonophoresis (using ultrasound to deliver medication) may be used.

Medications: This includes prescribing nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), acetaminophen for pain relief, or administering corticosteroid injections directly into the bursa. Bursal aspiration (draining fluid from the bursa) and injecting corticosteroids (with or without a local anesthetic) may also be performed.

Patients whose bursitis is linked to overuse should receive education on the importance of taking regular breaks and exploring alternative activities to prevent the bursitis from returning.

Applying cold packs for about 20 minutes at a time, several times a day, may be beneficial during the initial 24 to 48 hours. After this period, heat treatments might be more suitable.

Elevation is particularly helpful for bursitis in the legs or feet. Consider specific therapies for different locations (e.g., using cushions for ischial bursitis – affecting the buttocks – or wearing well-fitting, cushioned shoes for calcaneal bursitis – affecting the heel).

If septic bursitis is suspected, antibiotics should be started while waiting for the results of lab tests (cultures) to identify the specific bacteria. Superficial septic bursitis can often be treated with antibiotics taken by mouth on an outpatient basis.

Patients showing signs of systemic illness (like fever) or those with weakened immune systems might need to be hospitalized to receive antibiotics directly into their veins (intravenous or IV therapy).

Surgical removal of the bursa (bursectomy) might be considered for cases of chronic or frequently recurring bursitis. However, surgery is generally a last resort when conservative treatments haven’t been successful.

Medical Management

The medical treatment approach for bursitis varies depending on which bursa is affected and whether an infection is present.

Septic Bursitis

Systemic antibiotics: Antibiotics that travel throughout the body are the primary treatment for septic bursitis.

For bursitis caused by Staphylococcus aureus, antibiotics alone can often resolve the infection.

Sporothrix schenckii bursitis, a fungal infection, often requires surgical removal of the bursa (bursectomy) in addition to antifungal medication.

Most patients respond well to oral antibiotics, but some may need intravenous therapy.

Antimicrobial Regimens: Standard antibiotic choices for septic bursitis include:

For Staphylococcus aureus, methicillin-susceptible (MSSA):

Oxacillin 2 grams intravenously every 6 hours (q.i.d).

Dicloxacillin 500 milligrams by mouth every 6 hours (q.i.d).

For Staphylococcus aureus, methicillin-resistant (MRSA):

Vancomycin 1 gram intravenously every 12 hours (b.d).

Aseptic Bursitis

Aseptic bursitis is typically managed with the PRICEMM regimen.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are commonly used to reduce pain and inflammation.

Local corticosteroid injections may be considered for patients who don’t improve with initial treatments.

Subacromial Bursitis

Conservative treatments recommended for nearly all patients with subacromial bursitis include:

Physical therapy (PT): Exercises to improve shoulder strength and movement.

Scapular strengthening and postural reeducation: Exercises to improve the stability and position of the shoulder blade.

Shoulder exercises: Specific movements to restore range of motion and strength.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDs).

Prepatellar Bursitis

Conservative treatments recommended for nearly all patients with prepatellar bursitis (bursitis in front of the kneecap) include:

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDs) are often the first-line treatment.

Reduce physical activity: Avoiding activities that aggravate the knee.

PRICEMM regimen during the first 72 hours after the injury.

Physical therapy.

Local corticosteroid injections may be used for patients who don’t respond to initial therapy.

Olecranon Bursitis

Conservative treatments recommended for nearly all patients with olecranon bursitis (elbow bursitis) include:

PRICEMM regimen during the first 72 hours after the injury.

Avoidance of aggravating physical activity.

Most patients get better with these measures, so physical and occupational therapy are usually not needed.

Early aspiration (with or without injecting corticosteroids) may help if there’s a significant fluid buildup that’s bothersome.

Diagnostic aspiration should be done if the bursitis doesn’t improve with treatment, to check for a possible infection.

Trochanteric Bursitis

Conservative treatments recommended for nearly all patients with trochanteric bursitis (hip bursitis) include:

Modification of physical activity.

Weight loss, if applicable.

Physical therapy.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDs).

Local glucocorticoid injections are considered for patients whose symptoms don’t improve with other treatments.

Physical therapy and NSAIDs are generally the most effective treatments for trochanteric bursitis. Surgery is rarely needed.

Retrocalcaneal Bursitis

Conservative treatments recommended for nearly all patients with retrocalcaneal bursitis (heel bursitis) include:

PRICEMM regimen during the first 72 hours after the injury.

Exercises that stretch the Achilles tendon may be beneficial.

Limitation of activity and changing footwear to avoid irritation of the back of the heel.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDs).

Physical therapy.

Corticosteroid injections are generally not recommended due to the risk of adverse effects on the Achilles tendon.

Surgical Management

Bursectomy

Surgery is typically not the first line of treatment for bursitis. Bursectomy (surgical removal of the bursa) is usually reserved for patients with bursitis that is chronic, keeps coming back, or is infected.

Indications for surgical intervention (either through an open incision or an endoscopic approach) in patients with bursitis include:

When needle aspiration is not effective in draining an infected bursa.

The presence of a foreign object within a bursa close to the skin’s surface.

A nearby skin or soft tissue infection that requires surgical cleaning (debridement).

Critically ill or immunocompromised patients.

A chronically infected and thickened bursa.

Severe bursitis that doesn’t respond to other treatments and keeps recurring.

Prevention of Bursitis

Engaging in regular exercise.

Always warming up or doing stretches before physical activity.

Maintaining a healthy weight.

Strengthening the muscles around the joints.

Taking breaks from repetitive tasks.

Using knee pads when kneeling or elbow pads.

Avoiding sitting still for long periods.

Practicing good posture and positioning the body correctly during daily activities.

Complications of Bursitis

Chronic pain: If bursitis is left untreated, the bursa can become permanently thickened or enlarged, leading to ongoing inflammation and pain.

Muscle atrophy: Long-term reduced use of the affected joint can result in decreased physical activity and a loss of muscle mass around the joint.

Get in Touch

(+256) 790 036 252

(+256) 748 324 644

Info@nursesonlinediscussion.com

Kampala ,Uganda

© 2025 Nurses online discussion. All Rights Reserved Design & Developed by Opensigma.co