Neurological Disorders in Children

Subtopic:

Intracranial hemorrhage

An intracranial hemorrhage is a condition involving bleeding that occurs within the confines of the skull (cranium).

Hemorrhages inside the skull or brain typically begin abruptly, resulting from either external trauma or internal medical issues. Such bleeding can rapidly inflict brain damage and pose a serious, life-threatening risk.

Bleeding that occurs around or directly within the brain tissue is specifically termed a cerebral hemorrhage (or intracerebral hemorrhage). A hemorrhagic stroke refers to bleeding that originates from a blood vessel in the brain that has either leaked or ruptured.

Essentially, any instance of bleeding contained within the skull is categorized as an intracranial hemorrhage.

Causes of Intracranial Hemorrhage.

Head trauma, such as injuries sustained from falls, car accidents, sports-related incidents, or seizures (epilepsy), can cause bleeding.

Hypertension (high blood pressure) can weaken the walls of blood vessels over time, making them prone to leaking or breaking.

A blockage of an artery in the brain can occur when a blood clot forms locally or travels from another part of the body to the brain, obstructing blood flow.

A ruptured cerebral aneurysm involves the bursting of a weakened, balloon-like bulge in the wall of a brain blood vessel.

Leaking of malformed arteries or veins refers to the bleeding from blood vessels that have developed abnormally.

Bleeding tumors can cause hemorrhages as they grow and disrupt surrounding tissues and blood vessels.

Conditions linked to pregnancy or childbirth, including eclampsia (severe high blood pressure during pregnancy), can sometimes lead to intracranial hemorrhage.

Difficult delivery, such as obstructed labor where the baby cannot pass through the birth canal, can be a cause.

Assisted delivery methods, like the use of forceps or vacuum extractors, can sometimes contribute to bleeding.

Coagulopathy (blood clotting disorders) or the use of anti-coagulation medicine (e.g., warfarin, heparin), as well as inherent bleeding disorders like hemophilia or thrombocytopenia (low platelet count), increase the risk of bleeding.

Child abuse syndrome (shaken baby syndrome), involving violent shaking of an infant, can cause severe intracranial bleeding.

Postsurgical complications following procedures like craniotomy (surgical opening of the skull) or shunting (placement of a tube to drain fluid) can sometimes result in hemorrhage.

Pathophysiology

The brain lacks the ability to store oxygen, making it critically dependent on a network of blood vessels to consistently deliver oxygen and essential nutrients. When an intracranial hemorrhage occurs, the leakage or rupture of blood vessels can prevent oxygen from reaching the brain tissue that those vessels normally supply. The accumulation of blood from the hemorrhage also creates pressure within the skull, further hindering oxygen delivery to the brain.

If the interruption of blood flow due to a hemorrhage or stroke deprives the brain of oxygen for more than a brief period (around three to four minutes), brain cells begin to die. This damage extends to the affected nerve cells and the specific bodily functions they control.

Types of Intracranial Hemorrhage

Epidural hematoma: Bleeding between the skull and the outer layer of the brain’s covering (dura mater).

Subdural hematoma: Bleeding between the dura mater and the next layer of the brain’s covering (arachnoid mater).

Subarachnoid hemorrhage: Bleeding in the space between the arachnoid mater and the innermost layer of the brain’s covering (pia mater), often involving blood mixing with cerebrospinal fluid.

Intra cerebral hemorrhage: Bleeding directly within the brain tissue itself.

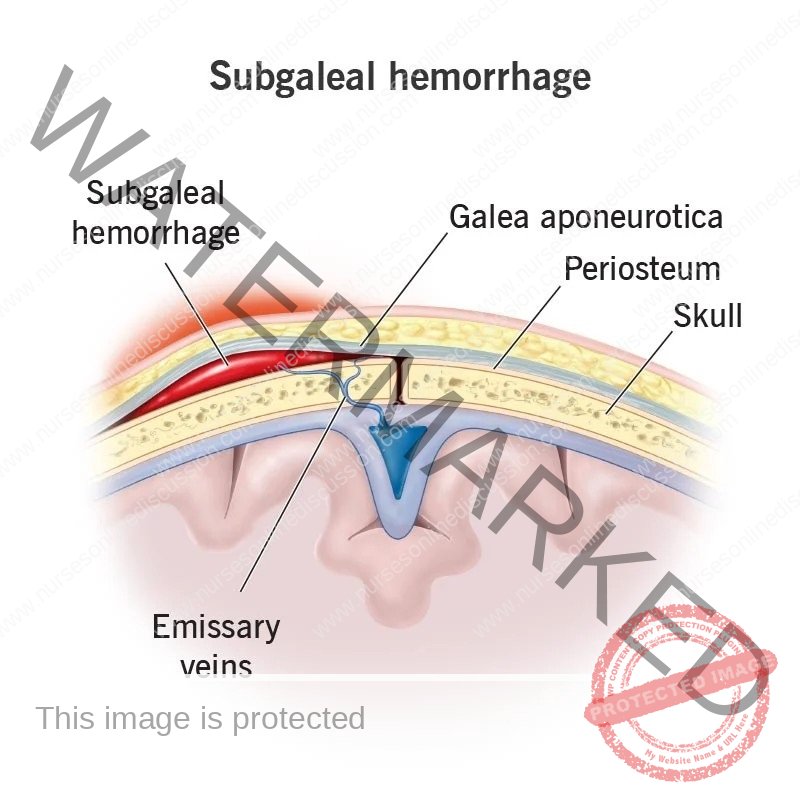

Epidural Hematoma (Subgalea hemorrhage)

Subgaleal hemorrhage occurs when the emissary veins, which connect the veins outside the skull to the venous sinuses inside the skull, are torn or sheared. This damage allows blood to collect in the space between the epicranial aponeurosis (a tough layer of fibrous tissue) and the periosteum (the outer layer of bone) of the skull. This type of hemorrhage is usually a consequence of a head injury and often accompanies a skull fracture. A key characteristic is high-pressure bleeding due to the arterial nature of the blood supply involved. An epidural hematoma might initially cause a brief loss of consciousness, followed by a return to consciousness before deterioration occurs again.

Epidural hematoma specifically refers to the accumulation of blood in the space between the dura mater (the outermost, thick membrane covering the brain and spinal cord) and the inner surface of the skull, typically resulting from a skull fracture.

It is most commonly caused by the rupture of the middle meningeal artery, which lies within this space.

The hematoma expands rapidly because the accumulating blood is arterial in origin, meaning it is under higher pressure. This rapid expansion leads to compression of the dura mater and a flattening of the underlying gyri (the folds of the cerebral cortex).

If the hematoma is not drained promptly, the patient will experience a progressive loss of consciousness as the pressure on the brain increases.

Signs and symptoms

Swelling of the ears: While not a direct symptom, swelling in the scalp region may extend to the ears.

Increasing head circumference as bleeding expands into this space. (hydrocephalus): The accumulation of blood can cause the head to enlarge. Although the mechanism is different from true hydrocephalus (which involves cerebrospinal fluid), the increased volume in the subgaleal space can lead to a similar outward appearance.

Hypovolemic shock: A condition where the body doesn’t have enough blood volume, leading to inadequate oxygen supply to the organs.

Tachycardia: An elevated heart rate, often the body’s attempt to compensate for low blood volume.

Hypotension: Abnormally low blood pressure, a sign of reduced circulating blood volume.

Diagnosis

Subgaleal hemorrhage can manifest as a large, soft, and compressible fluid collection that can be felt (palpable) on the surface of the head. A defining feature of a subgaleal hemorrhage is that the swelling is not restricted by the suture lines of the skull and may shift with movement of the head. This characteristic helps distinguish it from a cephalohematoma, which is a more common and superficial collection of blood located between the periosteum and the skull bone. A cephalohematoma’s spread is limited by the suture lines.

Neonates (newborn infants) with subgaleal hemorrhage face a significant risk of rapid decompensation (a quick decline in their condition). The subgaleal space has the potential to expand and hold an amount of blood equivalent to a newborn’s entire intravascular blood volume if the bleeding continues without recognition and treatment.

Subdural hematoma (SDH)

A subdural hemorrhage happens when the bridging veins, which transport blood from the brain through the dura mater (the tough outer membrane covering the brain) to the arachnoid mater (the middle layer of the meninges), are torn. This tearing leads to bleeding, and the blood collects beneath the dura mater and above the subarachnoid villi (small projections that help drain cerebrospinal fluid).

SDH is the accumulation of blood situated below the inner layer of the dura mater but on the outer side of the arachnoid membrane.

Subdural hematoma involves the collection of blood in the space between the dura mater and the subarachnoid membrane.

It most frequently develops due to the rupture of veins that traverse the surface convexities of the cerebral hemispheres (the folded outer layer of the brain).

Subdural hematomas can be classified as either acute or chronic.

Acute subdural hematoma arises following a traumatic injury. It consists of clotted blood and is often found in the frontoparietal region of the brain. Notably, there is usually no significant compression of the brain’s folds (gyri). Because the accumulated blood originates from veins (venous origin), the symptoms tend to appear gradually and can become a long-term issue (chronic) if not fatal.

Chronic subdural hematoma often occurs in individuals with brain atrophy (shrinkage of brain tissue). This type of hematoma is characterized by liquid blood. A membrane composed of granulation tissue (new connective tissue) forms, separating the hematoma from the underlying brain tissue.

Diagnosis

Since subdural bleeding occurs within the skull, there is often no visible physical sign of injury on the scalp. Consequently, the presence of a hemorrhage may initially go unnoticed. For the majority of newborns, a subdural hemorrhage remains asymptomatic and resolves without causing any lasting problems.

Clinical problems can emerge if there is a large amount of bleeding or if the bleeding continues slowly over a period of hours or even days, such as in cases involving bleeding disorders.

Symptomatic newborns commonly exhibit nonspecific signs 24–48 hours after birth, including apnea (pauses in breathing), respiratory distress (difficulty breathing), an altered neurologic state (changes in alertness or responsiveness), or seizures.

Subarachnoid hemorrhage

Subarachnoid hemorrhage occurs when the veins of the subarachnoid villi are torn, resulting in the collection of blood within the subarachnoid space. This means there is bleeding between the brain itself and the thin layers of tissue that cover the brain, known as the meninges.

A sudden, intense headache is a typical initial symptom of a subarachnoid hemorrhage. Other common symptoms include loss of consciousness and vomiting.

Bleeding into the subarachnoid space is most frequently caused by:

rupture of an aneurysm: Aneurysms are weak, bulging spots in the wall of a blood vessel.

rarely, rupture of a vascular malformation: Abnormal tangles of blood vessels in the brain.

Among the three main types of aneurysms that affect the larger arteries within the skull—berry, mycotic, and fusiform—berry aneurysms are the most clinically significant and the most common.

Berry aneurysms have a saccular appearance, resembling a sac or pouch, with rounded or lobulated bulges that arise at the branching points (bifurcations) of intracranial arteries. Their size can vary from 2 millimeters to 2 centimeters or even larger.

They account for the vast majority (95%) of aneurysms that are prone to rupture and cause bleeding.

Berry aneurysms are infrequent in childhood but become more prevalent in young adults and middle age. Therefore, they are not considered to be present at birth (congenital anomalies). Instead, they develop over time due to a developmental weakness in the middle layer (media) of the arterial wall at the points where arteries branch, leading to the formation of thin-walled, sac-like bulges.

While most berry aneurysms occur randomly, their presence is more common in individuals with certain conditions like congenital polycystic kidney disease (a genetic disorder causing cysts to form in the kidneys) and coarctation of the aorta (a narrowing of the main artery carrying blood from the heart).

In over 85% of cases of subarachnoid hemorrhage, the underlying cause is a sudden and massive bleed from a berry aneurysm located on or near the circle of Willis, a network of arteries at the base of the brain.

The four most frequent locations for these aneurysms to rupture are:

In close proximity to the anterior communicating artery.

At the point where the posterior communicating artery originates from the main part of the internal carotid artery.

At the first major branching point of the middle cerebral artery.

At the point where the internal carotid artery divides into the middle and anterior cerebral arteries.

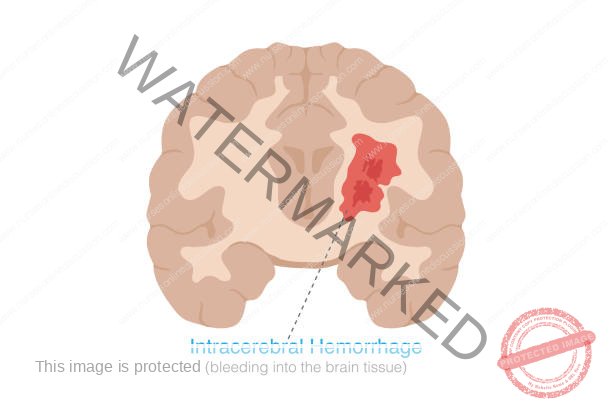

Intracerebral hemorrhage

Intracerebral hemorrhage refers to bleeding that occurs within the tissues of the brain.

This type of bleeding involves the leakage of blood into the brain’s ventricular system. This system is where cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is produced and circulates before moving towards the subarachnoid space. Intracerebral hemorrhage can be a result of physical trauma or can occur due to bleeding associated with a stroke, often linked to hypertension (HTN). It is the most frequent form of intracranial hemorrhage that is associated with a stroke, and unlike other types, it is usually not caused by an external injury.

Spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage is most commonly seen in individuals with a history of high blood pressure. Children who have systemic illnesses that cause high blood pressure are at an increased risk because they may develop tiny weakened areas (micro aneurysms) in the very small arteries within their brain tissue. It is believed that the rupture of one of these micro aneurysms is the primary cause of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage.

Unlike subarachnoid hemorrhages, recurrent intracerebral hemorrhages are not common.

The typical locations for intracerebral hemorrhage related to high blood pressure include the basal ganglia region (especially the putamen and the internal capsule), the pons (part of the brainstem), and the cerebellar cortex (the outer layer of the cerebellum).

Diagnosis

Observable clinical symptoms of Intracerebral hemorrhage can be limited. When they are present, signs may include a sudden decrease in hematocrit (the proportion of red blood cells in the blood), the new onset of low blood pressure, and a state of unresponsiveness or reduced alertness (lethargy). However, it is important to note that these signs are also commonly seen in very low birth weight babies and premature infants.

Signs and Symptoms

A significant warning sign is the abrupt onset of a neurological deficit, indicating a problem with brain function. These symptoms tend to worsen over a period of minutes to hours and can include:

Headache accompanied by neck stiffness: A severe headache often with an inability to easily move the neck.

Drowsiness: Feeling unusually sleepy or having difficulty staying awake.

Difficulty speaking/crying: Trouble forming words or producing sounds.

Nausea: Feeling sick to the stomach.

Vomiting: Expelling the contents of the stomach.

Decreased consciousness: A reduction in awareness and responsiveness to the environment.

Seizure: Uncontrolled electrical activity in the brain leading to physical convulsions.

Coma: A prolonged state of unconsciousness from which the person cannot be awakened.

Weakness in one part of the body: Reduced strength or inability to move a limb or one side of the body.

Elevated blood pressure: Higher than normal blood pressure readings.

Cognitive dysfunction or memory loss: Problems with thinking, understanding, or remembering information.

Sudden tingling, weakness, numbness, or paralysis of the face, arm or leg, particularly on one side of the body: Sensory or motor deficits affecting one side of the body.

Loss of balance or coordination in older children: Difficulty maintaining equilibrium or performing coordinated movements.

Babies less than 12 months old may develop a swollen fontanel, or soft spot: Bulging of the soft areas on a baby’s head where the skull bones haven’t yet fused.

Diagnosis

History taking: Gathering information about the patient’s symptoms and medical background.

Computed temography (CT- scan) of head: An imaging technique using X-rays to create detailed pictures of the brain.

MRI of head: Magnetic resonance imaging, using magnetic fields and radio waves to create detailed images of the brain.

CBC: Complete blood count, a blood test to measure different components of the blood.

Coagulation profile e.g. INR, PT: Blood tests to assess how well the blood is clotting.

Physical examination e.g. glasgow coma scale (GCS): A standardized tool to assess the level of consciousness.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| Motor response | None | Extensor | Abnormal Flexion | Normal Flexion | Localizes pain | Obeys command. |

| Verbal response | None | Incomprehensible sounds | Inappropriate word | Confusion | Spontaneous / Oriented | |

| Eye opening | None | To pain | To command/ speech | Spontaneous | ||

Management

Admission in icu or surgical paediatric ward: Requiring close monitoring and specialized care.

Resuscitation (ABC): Immediate steps to ensure Airway, Breathing, and Circulation. All patients with a GCS score of less than 8 should have a breathing tube inserted (intubated) to protect their airway.

Surgical management

ICH is a medical emergency: Prompt treatment is crucial for survival.

It may be necessary to operate to relieve the pressure on the skull (craniotomy): Surgery may be needed to reduce the pressure inside the skull caused by the bleeding.

Craniotomy: A surgical procedure to open the skull to remove the accumulated blood.

Endovascular treatment: Procedures performed inside blood vessels to treat the bleeding.

Aneurysm coiling: A procedure to block off the site of an aneurysm with a small coil.

Medical management

Steroids to reduce swelling: Medications to decrease inflammation in the brain.

Anticoagulants to reduce clotting: Medications to prevent further blood clot formation (this might seem counterintuitive in a hemorrhage, but it refers to preventing clots elsewhere that could lead to further strokes).

Ant seizure medications: Medications to prevent or control seizures.

Medications to counteract any blood thinners that you’ve been taking: Reversal agents to counteract the effects of blood-thinning medications.

Lower blood pressure to a mean arterial pressure less than 130 mm Hg, but avoid excessive hypotension: Controlling blood pressure to prevent further bleeding, but avoiding dangerously low blood pressure.

Avoid hyperthermia: Preventing an abnormally high body temperature.

Correct any identifiable coagulopathy with fresh frozen plasma, vitamin K, or platelet transfusions: Treating any underlying blood clotting problems with blood products or medications.

Lower blood pressure to a mean arterial pressure less than 130 mm Hg, but avoid excessive hypotension: (Repeated for emphasis).

Avoid hyperthermia: (Repeated for emphasis).

Correct any identifiable coagulopathy with fresh frozen plasma, vitamin K, or platelet transfusions: (Repeated for emphasis).

Initiate anticonvulsant definitely to control seizures: Promptly starting medication to manage seizures.

Facilitate transfer to the operating room or ICU: Ensuring timely transfer to the appropriate medical setting.

Consider nonsurgical management for patients with minimal neurological deficits: For patients with less severe symptoms, surgery may not be required.

Diet

Employ aspiration precautions and obtain evaluation of patient’s swallowing: Taking steps to prevent food or liquid from entering the lungs and assessing the patient’s ability to swallow safely.

Initiate enteral feedings as soon as possible: Starting feeding through a tube inserted into the stomach or intestines. The patient may require placement of a nasogastric tube (inserted through the nose to the stomach) or a percutaneous device (inserted directly through the skin into the stomach).

Activity

Maintain bed rest during the first 24 hours: Restricting movement initially to promote healing.

Follow with progressive increase in activity: Gradually increasing the level of physical activity as the patient recovers.

Avoid strenuous exercise: Refraining from intense physical activity during recovery.

Complications.

Seizures: Uncontrolled electrical activity in the brain.

Paralysis: Loss of the ability to move part or all of the body.

Memory loss: Difficulty remembering information or events.

Stroke: Further disruption of blood flow to the brain.

Permanent brain damage: Lasting injury to the brain tissue.

Cerebral coning: A dangerous condition where brain tissue is squeezed through openings in the skull.

Depression: A persistent feeling of sadness and loss of interest.

Bedsore: Skin damage caused by prolonged pressure on the skin (also known as pressure ulcers).

We are a supportive platform dedicated to empowering student nurses and midwives through quality educational resources, career guidance, and a vibrant community. Join us to connect, learn, and grow in your healthcare journey

Quick Links

Our Courses

Legal / Policies

Get in Touch

(+256) 790 036 252

(+256) 748 324 644

Info@nursesonlinediscussion.com

Kampala ,Uganda

© 2025 Nurses online discussion. All Rights Reserved | Design & Developed by Opensigma