Pediatric Conditions of the Respiratory System

Subtopic:

Apnea

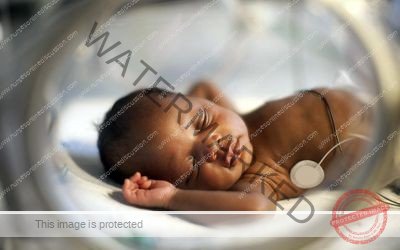

Apnea is clinically defined as the sudden cessation of breathing for a duration exceeding 20 seconds in full-term infants.

This event is frequently accompanied by a decrease in heart rate (bradycardia) and a bluish discoloration of the skin and mucous membranes due to low oxygen levels (cyanosis). Bradycardia, characterized by a heart rate below the normal range (typically less than 80-100 beats per minute in newborns), usually manifests approximately 30 seconds after breathing stops.

Apnea is a more commonly observed phenomenon in premature infants. In this specific context, it is classified as Apnea of Prematurity (AOP) and necessitates a distinct approach to assessment and management. Apnea is relatively uncommon in healthy, full-term infants, and its presence often signals an underlying medical condition or pathology.

Fundamentally, apnea represents a disruption in the normal control of respiration and can be categorized into obstructive, central, or mixed types.

Types of Apnea

Central Apnea: This form of apnea arises from a depression or malfunction within the respiratory center of the brain. Essentially, the brain fails to generate the necessary signals to stimulate the muscles responsible for breathing.

Obstructive Apnea: This type of apnea occurs when there is a physical blockage or obstruction of the upper airway. A common cause in infants is the collapse of the soft tissues in the throat, hindering the flow of air.

Mixed Apnea: As the name suggests, mixed apnea involves elements of both central and obstructive apnea occurring simultaneously.

NB: Short episodes of apnea are more likely to be of central origin, while longer, more sustained episodes are often classified as mixed apnea.

Causes of Apnea

Immature Respiratory System: Premature infants have lungs and associated respiratory structures that are not fully developed, making them more vulnerable to breathing irregularities, including apnea.

Brain Immaturity: The areas of the brain responsible for regulating breathing patterns are still developing in premature infants, leading to less stable respiratory control.

Neurological Problems: Underlying neurological conditions or impairments in premature babies can disrupt the normal signals that control breathing.

Systemic disorders: Various medical conditions affecting different organ systems can contribute to apnea:

Cardiovascular: Conditions such as anemia (low red blood cell count), low or high blood pressure (hypotension/hypertension), patent ductus arteriosus (an abnormal opening between major blood vessels), and coarctation of the aorta (a narrowing of the aorta) can compromise oxygen delivery and trigger apnea.

Central nervous system: Conditions affecting the brain, including bleeding within the ventricles of the brain (intraventricular hemorrhage), bleeding within the skull (intracranial hemorrhage), stroke affecting the brainstem (brainstem infarction), structural abnormalities of the brain, birth-related injuries (birth trauma), and congenital malformations, can all increase pressure within the skull and disrupt respiratory control.

Respiratory: Lung infections (pneumonia), masses or lesions within or outside the airways causing obstruction, collapse of the upper airway, lung collapse (atelectasis), respiratory distress syndrome (a breathing disorder in newborns), aspiration of meconium (first stool) into the lungs, and bleeding in the lungs (pulmonary hemorrhage) can all impair the ability to ventilate and oxygenate effectively.

Gastrointestinal: Activities like oral feeding, bowel movements, backflow of stomach contents into the esophagus (gastroesophageal reflux), and a serious intestinal disease (necrotizing enterocolitis) can sometimes be associated with apnea.

Metabolic: Imbalances in blood sugar (hypoglycemia), calcium (hypocalcemia), sodium (hyponatremia/hypernatremia), high levels of ammonia in the blood (hyperammonemia), low levels of certain organic acids, and abnormalities in body temperature (hypothermia/hyperthermia) can disrupt normal bodily functions, including breathing.

Infection: Infections, particularly respiratory infections, but also serious systemic infections like meningitis (inflammation of the membranes surrounding the brain and spinal cord) or encephalitis (inflammation of the brain), can worsen or trigger apnea episodes in vulnerable infants.

Medications: Exposure to certain medications can predispose infants to apnea. This can occur through the mother’s drug use during pregnancy (transplacental transfer) or after birth (postnatal exposure). Examples include opiates, high levels of phenobarbital (a sedative), other sedatives, and general anesthetic agents.

Pain: Both acute and chronic pain can sometimes trigger apnea episodes in infants.

Head and neck poorly positioned: Improper positioning of the infant’s head and neck can obstruct the airway and contribute to apnea.

Toxin exposure: Exposure to certain toxins can negatively impact respiratory control.

Clinical features of apnea

Episodes of no breathing: The most direct and observable sign is the cessation of respiratory effort for a sustained period.

Decreased heart rate (Bradycardia): A slowing of the heart rate below the normal range is a common physiological response to prolonged breath-holding.

Change in skin color (Cyanosis): The infant’s skin, particularly around the lips and fingertips, may develop a bluish or pale hue due to a lack of oxygen.

Irritability: Some infants experiencing apnea of prematurity may exhibit increased irritability or fussiness between episodes.

Poor feeding: Apnea episodes can interfere with an infant’s ability to coordinate sucking, swallowing, and breathing, leading to difficulties with feeding.

Management of Apnea

Aims of Management

Maintain Adequate Oxygenation: The primary goal is to ensure the infant receives a sufficient supply of oxygen. This prevents hypoxemia, a dangerous condition of low blood oxygen, and its potential complications.

Support Respiratory Function: Providing support to the infant’s breathing mechanisms is crucial to maintain effective respiration and minimize or prevent further episodes of apnea.

Prevent Complications: A key objective is to reduce the risk of complications associated with Apnea of Prematurity (AOP), such as potential brain damage, developmental delays, and long-term respiratory difficulties.

Assessment

Initially, observe the infant for visible signs of breathing and assess their skin color. If the infant is not breathing (apneic), appears pale, has cyanosis (bluish skin), or exhibits bradycardia (slow heart rate), provide tactile stimulation.

Gather information about the frequency and duration of apneic episodes, the degree of hypoxia (low oxygen levels) experienced, and the intensity of stimulation required to prompt the infant to breathe.

Note: If the infant does not respond to tactile stimulation, immediate intervention is necessary. This includes using bag-and-mask ventilation to assist breathing, along with suctioning to clear the airway and ensuring the airway is open through proper positioning.

For all infants born before 34 weeks of gestation (premature infants), continuous monitoring of heart rate, breathing patterns, and oxygen saturation levels is essential for at least the first week of life. This close monitoring continues until the infant has been free from any apneic pauses for a full week.

Neonates born at or after 34 weeks gestation generally only require continuous monitoring if they exhibit signs of instability or respiratory distress.

Acute Management

Positioning: Ensuring the neonate’s head and neck are in a neutral position is critical for maintaining an open and unobstructed airway. Avoid excessive flexion or extension of the neck.

Tactile stimulation: For mild and infrequent episodes of apnea, gentle stimulation, such as lightly rubbing the soles of the feet or the chest wall, is often sufficient to stimulate breathing.

Clear airway: Suctioning the mouth and nostrils removes any mucus or secretions that could be blocking the airway.

Provision of positive pressure ventilation: If spontaneous breathing does not resume quickly, providing breaths using a bag and mask may be necessary. If positive pressure ventilation is frequently required to treat apneic episodes, mechanical ventilation should be considered for more sustained respiratory support.

Continuous Positive Airway Pressure (CPAP): CPAP is an effective treatment option for both mixed and obstructive apnea, but it is generally not effective for central apnea. It is typically delivered through nasal prongs or an endotracheal tube. CPAP works by increasing the volume of air in the lungs and reducing the duration of each inhalation, which helps to prevent airway collapse. It also provides support and stability to the muscles of the chest wall.

Ongoing Management

Pulse oximeter: Continuous monitoring with a pulse oximeter allows for the detection of changes in heart rate, respiratory rate, and oxygen saturation levels that may occur due to apneic episodes.

Identify cause: If the apnea is not attributed to the normal physiological immaturity of prematurity, a thorough investigation is needed to identify and treat any underlying medical conditions contributing to the apnea.

Apnea monitor: This device detects movement of the abdominal wall associated with breathing. However, it’s important to note that apnea monitors may trigger false alarms with normal periodic breathing patterns seen in infants.

Caffeine citrate: Caffeine citrate can be administered either orally or intravenously and is commonly given routinely to neonates born before 34 weeks gestation. It acts as a smooth muscle relaxant, a stimulant for the heart muscle, and a stimulant for the central nervous system, which helps to regulate breathing.

High flow nasal Cannula (HFNC): HFNC can be particularly effective for managing mixed and obstructive apneas. It is often used when treatment with caffeine alone is not sufficient.

Mechanical ventilation: When other treatments like caffeine, HFNC, and CPAP have been tried and the infant continues to experience significant apneic episodes, mechanical ventilation may be necessary to provide full respiratory support. It is effective for all types of apnea.

Medical Management

Methylxanthines: This class of medications is frequently used in the medical management of apnea. Examples include caffeine, theophylline, and theobromine. These drugs work by blocking adenosine receptors in the body. Adenosine is a naturally occurring substance that inhibits the drive to breathe. By blocking these receptors, methylxanthines stimulate respiratory neurons, thereby improving ventilation.

Two commonly used methylxanthines are:

Caffeine Citrate: Due to its longer duration of action in the body (longer half-life) and lower risk of toxicity compared to other methylxanthines, caffeine citrate is often the preferred choice for the routine management of AOP, especially in premature infants.

Loading Dose: A starting dose of 20 mg per kilogram of body weight (20 mg/kg) is typically administered, either intravenously (IV) or orally (P.O.).

Maintenance Dose: A daily maintenance dose of 5 mg per kilogram of body weight per day (5 mg/kg/day) is usually given after the loading dose.

Theophylline: Theophylline also acts as a bronchodilator, which can be particularly beneficial for neonates who have bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD), a chronic lung condition common in premature infants. This dual action helps manage both apnea and airway constriction (bronchospasm).

Loading Dose: A starting dose of 6 mg per kilogram of body weight per dose (6 mg/kg/dose) is administered either intravenously (IV) or orally (P.O.).

Maintenance Dose: A daily maintenance dose of 6 mg per kilogram of body weight per day (6 mg/kg/day), divided into doses given every six hours, is usually prescribed.

Documentation and Family-Centered Care

Documentation: Thorough documentation of all apnea episodes is essential. This should include the interventions that were required to resolve the episode, the frequency of episodes, and their duration.

Parental Education:

Provide clear explanations to parents about the underlying cause of apnea in their infant and the rationale behind the chosen treatment approaches, such as the use of antibiotics for suspected infections.

Reassure parents that Apnea of Prematurity is a common condition in premature infants and typically resolves as the infant matures, usually by around 34 weeks gestation.

Offer clear and detailed explanations of all medical interventions being used, such as caffeine administration, Continuous Positive Airway Pressure (CPAP), or mechanical ventilation, and emphasize the importance of these interventions in managing their infant’s condition.

Nursing Care Plan for a Pediatric Patient with Apnea

1. Assessment:

The child is experiencing episodes of apnea lasting longer than 20 seconds, accompanied by cyanosis, and bradycardia (heart rate less than 100 bpm).

Nursing Diagnosis:

Ineffective Breathing Pattern related to immature respiratory control, as evidenced by episodes of apnea, cyanosis, and bradycardia.

Goals/Expected Outcomes:

The child will maintain effective breathing patterns with no episodes of apnea, and oxygen saturation will remain consistently above 95%.

Interventions:

Continuously monitor the child’s respiratory rate, effort, and oxygen saturation using a cardiorespiratory monitor.

Position the child in a supine or side-lying position with the head slightly elevated to facilitate airway patency.

Administer oxygen as prescribed to maintain adequate oxygenation.

Gently stimulate the child (e.g., rub the back or flick the soles of the feet) during apneic episodes to prompt breathing.

Prepare for possible resuscitation if apnea persists despite stimulation.

Rationale:

Continuous monitoring is crucial to detect apneic episodes and guide timely nursing interventions. Proper positioning promotes airway patency and reduces the risk of obstructive apnea. Administering oxygen improves oxygenation during and after apneic spells. Gentle stimulation often restarts breathing in infants experiencing apnea. Resuscitation equipment and trained personnel should be readily available in case stimulation is not effective in restoring breathing.

Evaluation:

The child maintains a normal breathing pattern, with no further episodes of apnea, and oxygen saturation remains within the target range consistently.

2. Assessment:

The child exhibits signs of fatigue and decreased responsiveness between apneic episodes.

Nursing Diagnosis:

Activity Intolerance related to recurrent apneic episodes, as evidenced by fatigue and decreased responsiveness.

Goals/Expected Outcomes:

The child will exhibit improved activity tolerance with increased periods of alertness and responsiveness.

Interventions:

Allow for rest periods between feedings and activities to reduce fatigue.

Monitor the child’s energy levels and responsiveness closely, adjusting activity levels as needed.

Educate parents on the importance of providing a calm, low-stimulation environment to promote rest.

Provide small, frequent feedings to minimize energy expenditure during feeding.

Rationale:

Rest periods help conserve the child’s energy and prevent excessive fatigue. Close monitoring allows for timely adjustments to activity levels based on the child’s energy reserves. A calm environment reduces stress and supports the child’s recovery. Small, frequent feedings reduce the effort required during feeding, thus conserving energy.

Evaluation:

The child demonstrates improved activity tolerance, with increased alertness and responsiveness between rest periods.

3. Assessment:

Parents express anxiety about the child’s condition and fear of apneic episodes occurring at home.

Nursing Diagnosis:

Anxiety related to fear of apneic episodes and uncertainty about the child’s condition, as evidenced by parental verbalization of concern.

Goals/Expected Outcomes:

The parents will verbalize understanding of the child’s condition and demonstrate confidence in managing apneic episodes at home.

Interventions:

Provide clear, concise information to the parents about apnea, including causes, signs, and interventions.

Teach parents how to monitor the child’s breathing and how to respond to apneic episodes at home, including the use of home monitoring equipment if prescribed.

Offer emotional support and reassurance, acknowledging the parents’ feelings and concerns.

Encourage parents to ask questions and participate in the child’s care to increase their confidence.

Rationale:

Educating parents helps reduce anxiety by providing them with the knowledge and skills needed to manage the child’s condition. Hands-on teaching and use of monitoring equipment empower parents to respond effectively to apneic episodes. Emotional support reassures parents and validates their concerns. Involving parents in care increases their confidence and sense of control.

Evaluation:

The parents verbalize understanding of the child’s condition, demonstrate correct management of apneic episodes, and express increased confidence in caring for their child at home.

4. Assessment:

The child is at risk for impaired gas exchange due to recurrent apneic episodes.

Nursing Diagnosis:

Risk for Impaired Gas Exchange related to apneic episodes and immature respiratory control.

Goals/Expected Outcomes:

The child will maintain adequate gas exchange as evidenced by normal oxygen saturation levels and absence of cyanosis.

Interventions:

Monitor oxygen saturation and signs of respiratory distress continuously, intervening promptly during apneic episodes.

Administer supplemental oxygen as needed to maintain target oxygen saturation levels.

Provide continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) or mechanical ventilation if prescribed to support the child’s respiratory efforts.

Monitor arterial blood gases (ABGs) or transcutaneous CO2 levels if indicated to assess gas exchange.

Rationale:

Continuous monitoring allows for prompt intervention during episodes of impaired gas exchange. Supplemental oxygen supports adequate oxygenation during apneic episodes. CPAP or mechanical ventilation provides respiratory support in cases of severe or persistent apnea. Monitoring ABGs or CO2 levels provides information on the child’s gas exchange status, guiding treatment.

Evaluation:

The child maintains adequate gas exchange, as evidenced by oxygen saturation levels within normal limits and absence of cyanosis.

5. Assessment:

The child is at risk for infection due to immature immune system and potential aspiration.

Nursing Diagnosis:

Risk for Infection related to immature immune system and potential aspiration.

Goals/Expected Outcomes:

The child will remain free from infection as evidenced by normal temperature and absence of signs of infection.

Interventions:

Practice strict hand hygiene and aseptic technique during all care activities.

Monitor for signs and symptoms of infection, including fever, changes in feeding habits, or respiratory distress.

Ensure proper positioning during and after feedings to minimize aspiration risk.

Limit exposure to potential sources of infection, when possible.

Rationale:

Strict hand hygiene and aseptic technique are essential to prevent the spread of infection. Early detection of infection through vigilant monitoring allows for prompt treatment. Proper positioning during and after feeding reduces the risk of aspiration, a potential source of infection. Limiting exposure to pathogens helps to protect the child with an immature immune system.

Evaluation:

The child remains free from infection, evidenced by normal body temperature and absence of clinical signs of infection.

Get in Touch

(+256) 790 036 252

(+256) 748 324 644

Info@nursesonlinediscussion.com

Kampala ,Uganda

© 2025 Nurses online discussion. All Rights Reserved Design & Developed by Opensigma.co