Medical Nursing (III)

Subtopic:

Tendonitis or Tendinitis

Tendonitis is a condition characterized by the swelling or aggravation of a tendon. A tendon is a thick, fibrous cord that connects muscles to bones.

Tendinitis can affect any of the numerous tendons throughout your body. However, it is more frequently observed in the areas surrounding your shoulders, elbows, wrists, knees, and heels. These are areas where tendons are heavily used and subjected to repetitive stress.

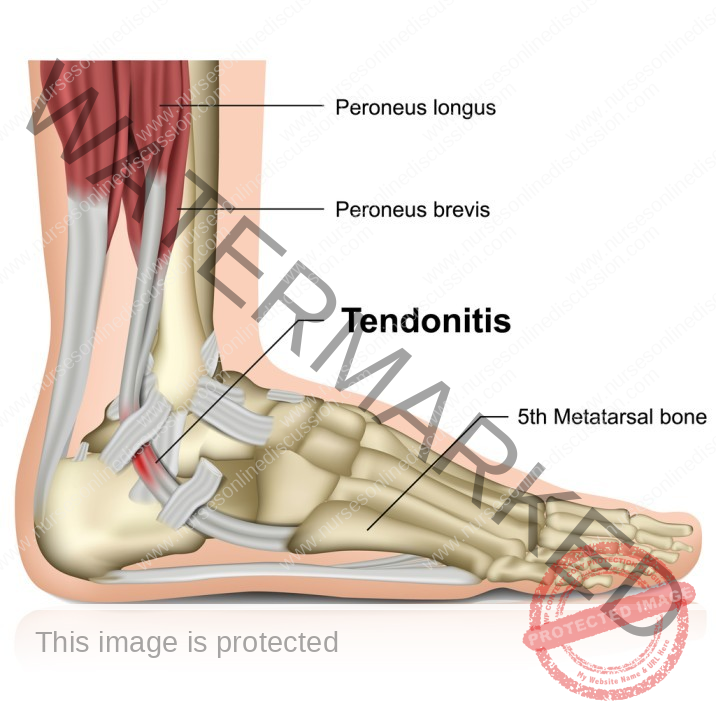

Anatomy Review

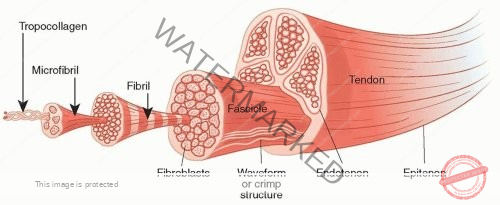

A tendon is a resilient band of fibrous connective tissue that links a muscle to a bone. This connection is essential for movement.

Tendons enable limb movement and play a crucial role in safeguarding muscles from injury by absorbing some of the force generated during activities like running, jumping, and other physical actions. The human body contains a vast network of tendons.

Tendons are vital for body mechanics and movement. They act as transmitters of the force generated by muscle contractions to the bones, allowing for both movement and the maintenance of posture.

The primary cell types within tendons are tenocytes (previously known as fibrocytes) and tenoblasts (previously known as fibroblasts), both of which are specialized connective tissue cells. Tenocytes are mature tendon cells found throughout the tendon structure, typically anchored to the collagen fibers that form the tendon’s main substance. Tenoblasts are considered immature tendon cells, also spindle-shaped, that are the precursors to tenocytes. Tenoblasts are often seen in clusters and are actively involved in producing collagen and other components of the extracellular matrix, the non-cellular part of the tendon.

A tendon sheath is a membrane-like layer that surrounds certain tendons. This structure helps to separate the tendon from surrounding tissues, allowing it to glide smoothly and with minimal friction during movement.

Tendons are known for their stiffness and high tensile strength, meaning they can withstand significant loads with only slight changes in shape. It’s important to distinguish tendons from ligaments, which are another type of connective tissue but connect bones to other bones. Another related term is tendinosis, which describes a chronic condition involving the breakdown of tendon tissue over time, unlike the primarily inflammatory nature of tendonitis.

Common Types of Tendonitis

Achilles tendonitis is a frequent injury, especially among athletes. Individuals with rheumatoid arthritis also face a higher risk of developing inflammation in this major tendon of the ankle.

Tennis elbow, clinically known as lateral epicondylitis, is a painful condition resulting from the overloading of tendons in the elbow. This is typically caused by repetitive movements of the arm and wrist. Wrist tendonitis can affect anyone who repeatedly performs the same motions with their wrists. It is a common issue for those who spend considerable time typing, writing, or participating in sports such as tennis.

Golfer’s elbow, or medial epicondylitis, is characterized by pain extending from the elbow down to the wrist on the inner (medial) side of the elbow. It can also be referred to as baseball elbow, suitcase elbow, or forehand tennis elbow.

Pitcher’s shoulder occurs when muscles or tendons in the shoulder are overworked, leading to inflammation. The rotator cuff, a group of muscles and tendons surrounding the shoulder joint, is often affected in throwing athletes.

Swimmer’s shoulder, also known as shoulder impingement, is a condition where the constant rotation of the shoulder joint during swimming can irritate the tendons. In supraspinatus tendonitis, a specific tendon located at the top of the shoulder joint becomes inflamed, causing pain when the arm is moved.

Jumper’s knee, medically termed patellar tendonitis, involves inflammation of the patellar tendon, which connects the kneecap to the shinbone.

Causes of Tendonitis

Tendonitis can be triggered by a sudden injury. However, it is more commonly the result of repeated stress on the tendon over an extended period.

Strain refers to the overstretching or tearing of a muscle or the tendon that connects a muscle to a bone.

Overuse of tendons or excessive engagement in exercises can place undue stress on these structures, leading to inflammation.

Direct injury or trauma to a tendon can also be a cause of tendonitis.

Risk factors

Age is a contributing factor, as tendons tend to lose some of their flexibility as people get older.

Participation in certain sports and exercises that involve repetitive motions increases the risk of tendonitis.

Underlying medical conditions such as diabetes and rheumatoid arthritis can make individuals more susceptible to tendon issues.

Certain antibiotics, such as quinolones (including ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin), have been linked to an increased risk of tendon problems. Direct trauma or injury to the tendon can also be a risk factor.

Pathophysiology

The underlying cause of tendonitis is the irritation of the tendon sheath due to prolonged or abnormal use of the tendon. Tendon sheaths are thin layers of tissue that facilitate the smooth gliding of tendons. In less frequent cases, bacterial invasion of the tendon sheaths can lead to infection.

Inflammation within the tendon sheath results in swelling, redness, and pain along the affected tendon. Movement of the tendon exacerbates this pain. The swelling of the sheath can narrow the space available for the tendon to slide, causing stiffness in the area. A grating or crackling sensation may be felt as the tendon moves within the inflamed sheath.

Signs and symptoms

★ Redness and Hotness at the affected site indicate inflammation and increased blood flow.

★ Pain is often described as a persistent, dull ache, which is particularly noticeable when moving the affected limb or joint. The pain typically intensifies with movement of the injured area.

★ Tenderness to the touch is a common symptom. Applying pressure to the affected area will elicit increased pain.

★ Mild swelling may be present around the inflamed tendon.

★ A feeling of grating or crackling when the tendon is moved can occur due to the inflamed surfaces rubbing against each other.

★ Tightness in the affected area can make movement difficult and restricted.

Diagnostic management

A thorough Physical examination by a healthcare provider is usually the first step in diagnosis.

MRI scans can provide detailed images of the tendons and surrounding tissues, helping to identify thickening, dislocations, and tears.

X-ray imaging may be used to rule out other conditions, such as bone fractures.

Ultrasound can also be used to visualize tendons and assess for inflammation or damage.

Pharmacological / Medical Management

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are commonly used to relieve pain and reduce inflammation.

Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) therapy involves taking a sample of the patient’s blood, processing it to concentrate the platelets and growth factors, and then injecting this solution into the area of chronic tendon irritation to promote healing.

Corticosteroid injections can be administered to reduce inflammation directly at the site. However, they are generally not recommended for chronic tendinitis (lasting over three months) as repeated injections can weaken the tendon and increase the risk of rupture.

Treating underlying conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis and diabetes is an important aspect of managing associated tendonitis.

Surgical management

For cases of chronic tendon inflammation, focused aspiration of scar tissue (FAST) is a minimally invasive treatment option. This procedure uses ultrasound guidance and specialized small instruments to remove scar tissue from the tendon while minimizing disruption to the surrounding healthy tendon tissue.

Nursing interventions (specific)

★ Encouraging adequate rest from activities that aggravate the tendon is crucial for healing.

★ Instructing the patient on the proper use of heat or cold therapy as prescribed. Emphasize the importance of using a barrier between the skin and the heat source and using cold therapy carefully to prevent burns or frostbite.

★ Wrapping the affected area with a compression bandage can help to reduce swelling.

★ Educating the patient on how to apply heat or ice correctly to avoid skin damage from burning or excessive cooling.

★ In some cases, fluid removal by aspiration and physical therapy to prevent “frozen” joints and maintain range of motion may be part of the treatment plan.

★ Advising on resting or elevating the affected tendon to minimize swelling and promote healing.

★ Recommending the use of supports such as splints, braces, or a cane to provide stability and reduce stress on the tendon.

★ Explaining the importance of anti-inflammatory medications and advising patients to take them with milk or food to minimize gastrointestinal (GI) upset.

★ Suggesting the use of shoe inserts, if recommended, to ensure proper foot positioning during walking and running.

★ Implementing physical therapy which may include stretching exercises, massage, ultrasound therapy, and strengthening exercises to improve the tendon’s function and mobility.

Complications

Contractures, or the tightening of the tendon, can limit movement.

Scarring within the tendon, known as adhesions, can also restrict movement and cause pain.

Muscle wasting (atrophy) can occur due to decreased use of the affected limb.

Disability, ranging from mild to severe, can result from persistent tendonitis.

Get in Touch

(+256) 790 036 252

(+256) 748 324 644

Info@nursesonlinediscussion.com

Kampala ,Uganda

© 2025 Nurses online discussion. All Rights Reserved Design & Developed by Opensigma.co