Introduction of Nursing Research

Subtopic:

Formulation of Research Topics

Table of Contents

Learning Objectives

- Define a research topic and explain its role in guiding the research process.

- Describe the relationship between research problems, topics, objectives, and questions.

- Identify sources and steps for formulating a research problem.

- Apply the FINER criteria to evaluate the quality of a research problem.

- Distinguish between general and specific research objectives and formulate each effectively.

- Use action verbs and SMART criteria to construct clear, measurable research objectives 1.

Introduction

Often, researchers consider potential research topics even before they have fully defined a research problem. However, the development of a compelling research topic usually originates from a researcher’s recognition of specific issues that they feel are important to investigate through systematic inquiry.

This suggests that identifying a clear problem is generally the first step in the research process, naturally leading to the creation of a relevant research topic, which then guides the formation of focused objectives and pertinent research questions.

Therefore, a research topic can be understood as the overarching theme or central concept that provides direction and focus for the entire research endeavor. The research topic is frequently referred to as the title of the research project.

Imagine research as a tree: the research topic acts as the strong trunk, providing the central support and direction for all other elements of the study.

The Research Process as a Tree

The research process should be interconnected and logically flow, with each element building upon the last.

Roots (Research Topic): Just as roots anchor a tree, the research topic provides a firm foundation for all research ideas and activities. All aspects of the research should align with and stem from the central topic.

Stem (Middle Ideas and Activities): The stem represents the core processes and actions of the research, connecting the foundational topic to the more detailed aspects.

Branches, Leaves, and Fruits (Conducting Research): These elements symbolize the practical execution of the research.

Branches: Represent the different stages and methodologies employed in the research process.

Leaves: Symbolize the detailed data collection and analysis procedures.

Fruits (Research Findings): Represent the outcomes and results of the research. Ideally, these “fruits” (findings) should be directly related to the “seed” planted, meaning the information obtained should directly address and be relevant to the initial research topic.

Example Topic: “A study on knowledge and practice among mothers of neonates in Soba Village, Jota District.”

Research Problems

Research problems are the specific issues, concerns, or gaps in knowledge that a researcher identifies in a situation and seeks to address through investigation and information gathering.

Definition of a Research Problem:

A research problem is the specific issue or question that a researcher aims to explore, investigate, or solve. It is a statement describing an area of concern, a condition needing improvement, or a challenge to be addressed through systematic inquiry.

Sources of Research Problems:

Research problems can arise from various sources, prompting investigation and discovery. Common sources include:

Personal Interest and Experience: Direct experiences or enduring curiosity about a particular phenomenon can spark research questions.

Intellectual Curiosity: A natural inquisitiveness and desire to understand “how” and “why” things are the way they are. Asking questions and seeking explanations.

Recommendations from Prior Research: Identifying areas for further study suggested by previous researchers in their work.

Program Evaluation: Evaluating the effectiveness of a specific program or intervention can reveal gaps or areas needing further research.

Direct Observation of Community Needs: Recognizing and identifying current needs or issues within a community that require research-based solutions. Applied research often originates from addressing these practical needs.

Examples of Research Problems (Expressed as Questions):

Researchers often begin by formulating questions that pinpoint the research problem. Examples include:

Cholera Outbreak Cause: “What factors are contributing to the recent cholera outbreak among residents of Katanga?” (Focuses on identifying causes)

Malaria Age Group Prevalence: “Which age demographic is most significantly affected by malaria within the Mulago region?” (Focuses on identifying prevalence within a population group)

Key Elements in Problem Identification:

When formulating a research problem, it is important to clearly specify:

The Problem: The specific issue or phenomenon being investigated.

The Affected Population: The group of individuals or entities impacted by the problem.

The Study Area (Location): The geographical or contextual setting where the problem is being studied.

Qualities/Characteristics of a Good Research Problem (FINER Criteria):

A well-formulated research problem possesses specific qualities, often summarized by the acronym FINER:

F – Feasible: The research problem should be realistically researchable given available resources, time, and access to participants.

Example: Assessing the practicality of introducing a new telehealth service in a rural clinic with limited internet access.

I – Interesting: The problem should be genuinely intriguing to the researcher and ideally to others in the field. This intrinsic interest is crucial for sustained motivation throughout the research process.

Note: It’s beneficial to confirm that your interest in the topic is shared by others in your field.

Example: Investigating the lived experiences of nurses working in high-stress emergency departments.

N – Novel: Good research contributes new information or insights to the existing body of knowledge. The problem should explore an area that is not overly researched or already well-established.

Example: Studying the impact of a newly developed mindfulness intervention on reducing burnout in healthcare professionals.

E – Ethical: The research must be conducted ethically, ensuring the safety, well-being, and rights of participants. It should avoid causing physical or psychological harm and protect privacy.

Example: Ensuring anonymity and confidentiality in a study exploring sensitive patient experiences.

R – Relevant (or Significant): The research should be relevant and have the potential to make a meaningful contribution to society, the field of study, or inform policy. Consider how the findings might advance knowledge, improve practices, or influence policy decisions.

Example: Evaluating the effectiveness of a community-based health education program in improving vaccination rates.

FINER Criteria in Detail with Examples:

Acronym | Description | Related Examples |

F | Feasible – The research problem should be realistically researchable in terms of cost, time, available respondents, and resources. | Example: Assessing the feasibility of implementing a new mobile health application for medication adherence in a resource-constrained community. This considers whether the technology is accessible and affordable for the target population and within the research budget. |

I | Interesting – The problem should be sufficiently intriguing to maintain the researcher’s motivation and overcome research challenges. | Example: Investigating the impact of a novel music therapy intervention on reducing anxiety in pediatric patients undergoing chemotherapy. This topic is likely to be interesting to researchers concerned with innovative approaches to patient comfort and well-being in challenging medical contexts. |

N | Novel – Good research adds new knowledge and should not be overly common or extensively studied already. | Example: Studying the effects of a newly discovered gut microbiome composition on the effectiveness of immunotherapy for a specific type of cancer. This research is novel as it explores a cutting-edge area of scientific inquiry (microbiome research) in relation to a complex medical treatment. |

E | Ethical – The research must adhere to ethical principles, avoiding physical or psychological risks to participants and protecting their privacy. | Example: Ensuring strict patient confidentiality and obtaining informed consent from all participants in a study on sensitive mental health conditions. Ethical considerations are paramount, especially when dealing with vulnerable populations or sensitive topics. |

R | Relevant or Significant to Society – The research results should advance scientific understanding and have potential implications for practice, policy, or health outcomes. | Example: Investigating the effectiveness of different vaccination strategies to control a contagious disease outbreak in a densely populated urban area. This research is relevant as it can directly inform public health policies and strategies aimed at disease prevention and control, potentially impacting a large population. |

Examples of Research Topics and FINER Qualities:

To further illustrate the FINER criteria, consider these example research topics:

1. Research Topic: Exploring the Impact of Nurse Staffing Ratios on Patient Safety in Intensive Care Units

Feasible: Data on nurse staffing levels and patient safety outcomes can be collected from hospital records and staff surveys.

Interesting: Addresses a critical healthcare issue: establishing evidence-based staffing guidelines to improve patient safety.

Novel: Focuses specifically on the ICU setting, where patient needs are complex and acuity is high, adding to existing staffing research.

Ethical: Patient confidentiality will be protected, and ethical research guidelines will be strictly followed.

Relevant: Findings can inform healthcare policies and staffing practices, leading to enhanced patient care and safety in ICUs.

2. Research Topic: Investigating the Impact of a Nurse-Led Education Program on Diabetes Management in Underserved Communities

Feasible: A nurse-led education program can be implemented and evaluated in underserved areas, assessing its practicality and effectiveness.

Interesting: Addresses healthcare disparities in underserved populations and explores nurse-led interventions for chronic disease management.

Novel: Focuses on underserved populations often overlooked in diabetes management program research, filling a specific gap.

Ethical: Prioritizes participant well-being and ensures access to quality education and healthcare resources within the program.

Relevant: Outcomes can inform resource allocation and healthcare policies to support underserved communities in effective diabetes management.

Steps in Formulating a Research Problem

Albert Einstein famously stated, “The formulation of a problem is often more essential than its solution.” This highlights the critical importance of carefully defining the research problem. A structured approach to problem formulation involves these steps:

Identify a Broad Subject Area of Interest (Problem Identification): Begin by identifying a general area or topic that sparks your curiosity and aligns with your interests. This involves exploring potential research problems by:

Observing symptoms or issues.

Consulting with experts in the field.

Conducting preliminary literature searches to understand the existing knowledge base.

Identifying gaps in current knowledge or understanding.

Seeking ways to improve existing methodologies or approaches.

Dissect the Broad Area into Sub-areas: Break down the broad subject area into more specific and manageable sub-topics or areas of focus.

Select Area of Most Interest (Problem Selection): From the sub-areas, choose the specific area that is most compelling and aligns with your research goals and available resources. Consider factors such as:

Your personal interest in the sub-area.

The potential significance and impact of research in this area.

Availability of resources (data, funding, expertise).

Feasibility of finding a meaningful and researchable solution within this specific sub-area.

Raise Research Questions (Problem Definition): Formulate specific research questions that are focused, clear, and directly address the chosen problem area. These questions should guide your investigation.

Formulate Objectives: Develop clear and concise research objectives that outline what you aim to achieve through your research. Objectives should be specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound (SMART).

Assess Objectives: Critically evaluate your research objectives to ensure they are realistic, feasible, and directly address the research problem and questions you have identified.

Double-Check and Refine: Review and refine all aspects of your research problem formulation. Ensure that the problem is clearly defined, well-justified, and that your research questions and objectives are logically aligned with the problem statement. Properly explaining and justifying each element is essential for a strong research foundation.

Example to Better Understand the Steps in Research Problem Formulation

Let’s illustrate the steps of research problem formulation with a concrete example:

1. Problem Identification:

Scenario: Researchers in a pediatric hospital setting observe a potential research problem: medication errors.

Evidence: This identification stems from:

Direct observations of clinical practice.

Review of incident reports documenting medication-related incidents.

Discussions with nurses, pharmacists, and physicians who express concerns about medication errors.

Observation: An apparent increase in medication errors suggests a problem requiring investigation to understand its nature and extent.

2. Problem Selection:

Problem: The identified problem is “medication errors in a pediatric hospital setting.”

Evaluation: Researchers now need to assess if this problem is suitable and worthwhile for further investigation. They consider:

Researcher Interest: Is the research team genuinely interested in this issue?

Research Significance: Does addressing medication errors have important implications for patient care?

Resource Availability: Are there sufficient resources (time, funding, data access, expertise) to conduct a meaningful study?

Feasibility of Solution: Is it likely that the research can contribute to finding practical solutions or improvements?

Decision: The research team concludes that medication errors in pediatric care are indeed a significant problem with substantial impact on patient safety and quality of care. They also determine that their hospital setting provides the necessary resources and support to conduct a thorough and impactful study. Therefore, they select this problem for further research.

3. Problem Definition:

Selected Problem: “Medication errors in a pediatric hospital setting.”

Refinement: Researchers now define the research topic more specifically, outlining the scope, purpose, motivation, and expected outcomes of their study.

Topic Definition Example: The research topic is defined as: “Understanding the underlying causes of medication errors in a pediatric hospital setting and exploring effective strategies to prevent and mitigate these errors.“

Purpose Clarification: The overall purpose of the research is clearly stated: to improve patient safety in the pediatric unit and to optimize medication administration practices to minimize errors.

Seamless Progression:

As demonstrated in this example, the steps in problem formulation flow logically:

Identification: Recognizing the initial issue of medication errors.

Selection: Determining that this issue is important and researchable.

Definition: Clearly outlining the specific focus and aims of the research project related to medication errors.

Using the same example throughout this process ensures clarity and consistency in the research focus, from initial problem recognition to a well-defined research direction.

Objectives of the Study

Let’s consider another example to understand research objectives:

Example Research Problem:

“Over the past few years, it has been observed that 30% of newborns in Village X develop cord infections, leading to delayed healing. Tragically, a number of these babies die from neonatal tetanus. The precise extent and contributing factors to this problem are not fully understood.”

Research Objectives Defined:

Research objectives clearly state what the study intends to achieve. They are directly derived from the research problem. Objectives are categorized as:

Broad Objective (General Objective/Aim):

This is a statement of the overall intention of the research in general terms.

It describes the main overarching goal of the study.

Example: “The aim of this study is to establish the knowledge and practices of mothers regarding newborn umbilical cord care in Village X.”

Specific Objectives:

These are detailed, logically connected sub-goals that break down the broad objective into smaller, more manageable parts.

Specific objectives directly address the various aspects of the research problem and research questions.

They clearly specify what the study will do, where it will be conducted, and for what purpose.

How to Formulate Effective Objectives:

Well-stated objectives are crucial for guiding the research. Ensure your objectives are:

Coherent and Logical: Objectives should address different facets of the problem in a structured and logical sequence, building upon each other.

Operationally Defined: Objectives must be phrased in clear, actionable terms, specifying exactly what the research will do, in what setting, and for what reason.

Realistic: Objectives should be achievable within the context of local conditions, available resources, and time constraints.

Action-Oriented: Use action verbs that are specific and measurable, allowing for evaluation of whether the objective has been met.

Examples of Strong Action Verbs: To determine, to compare, to verify, to calculate, to describe, to establish, to assess, to identify, to evaluate.

Avoid Vague Non-Action Verbs: Refrain from using verbs that are not easily measurable or assessable.

Examples of Weak Non-Action Verbs: To appreciate, to understand, to study, to explore, to learn about, to become aware of.

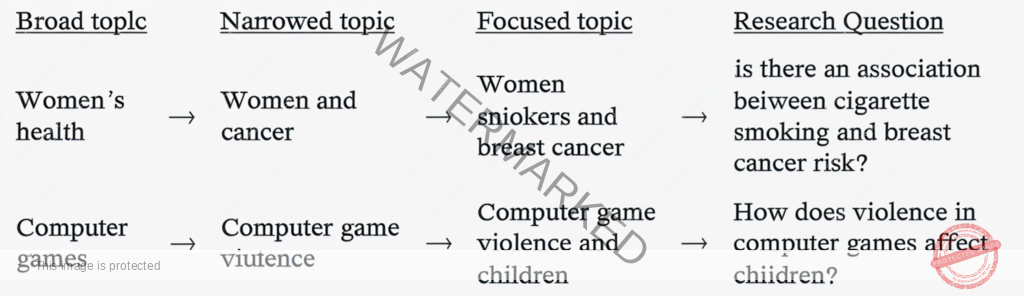

Developing a Research Topic/Question: A Step-by-Step Approach

To effectively develop a strong research topic and question, follow these steps:

Identify a Broad Subject Area: Begin by selecting a general subject area that interests you and has potential for investigation.

Example: Diarrheal diseases in children.

Conduct Preliminary Research: Explore existing literature and research on your general topic. This helps you understand:

What research has already been done in this area.

What is currently known and understood about the topic.

Identify Information Gaps: Based on your preliminary research, pinpoint “information gaps” or areas where knowledge is lacking or incomplete.

Example: You might find studies on the prevalence of diarrheal diseases but less information on the specific causes or risk factors in a particular population.

Ask:

“What do we already know about diarrheal diseases?” (e.g., general knowledge, existing research findings).

“What do we still need to know?” (e.g., specific causes, risk factors, effective interventions).

Formulate Broad Questions: Based on the identified information gaps, develop broad, open-ended questions that reflect what you want to investigate.

Example: “What are the key factors contributing to diarrheal diseases in young children?”

Narrow to a Specific Population: Refine your broad questions by focusing on a specific population group to make your research more manageable and targeted.

Example: “What are the risk factors for diarrheal diseases specifically among children less than one year old?”

Refine Scope and Focus: Further narrow the scope and focus of your research to create a clear and feasible research topic and question.

Example: “Assessment of risk factors associated with diarrheal diseases among children under one year of age in [Specific Location/Community].”

By following these steps, you move from a broad area of interest to a well-defined and researchable topic and question that can effectively guide your study.

Research Objectives

A research objective is a precisely stated, concise declaration that directs the investigation of variables within a study.

A clearly defined objective provides essential direction for researchers.

Well-defined objectives are a hallmark of a robust research study.

Without clear objectives, research can become aimless and lack direction.

Focused objectives are essential for producing replicable and reliable scientific findings.

Why are Research Objectives Important?

Research objectives serve several critical functions in guiding a study:

FOCUS: A well-defined objective ensures the researcher remains focused throughout the study. Formulating research objectives helps to narrow the scope of the study to its most essential elements. This focus prevents the collection of extraneous data and the wasteful use of resources.

AVOID UNNECESSARY DATA: Clearly defined research objectives prevent the accumulation of irrelevant data. By knowing exactly what needs to be investigated, researchers can avoid collecting data that does not directly contribute to answering the research question.

ORGANIZATION: Objectives structure the research into clearly defined stages or phases. This structured approach helps to organize the study’s results logically, presenting them in a manner that directly corresponds to the pre-set objectives.

GIVES DIRECTION: Well-formulated objectives guide the development of the research methodology. They provide a clear path for data collection, analysis, interpretation, and utilization, ensuring that all research activities are aligned with the study’s goals.

Characteristics of a Good Research Objective

A well-defined research objective should adhere to the “SMART” criteria:

S – SPECIFIC: A robust research objective is sharply defined and concentrates on a particular aspect or goal of the study. It avoids excessive breadth or ambiguity, ensuring researchers have a clear understanding of what they aim to achieve.

M – MEASURABLE: The objective must be measurable, meaning there should be a way to assess whether the research goal has been accomplished. Using concrete and quantifiable terms is crucial for evaluating outcomes.

A – ATTAINABLE: The research objective needs to be realistically achievable within the given resources, timeframe, and scope of the study. Setting attainable goals ensures that the research can be completed successfully with the available means.

R – REALISTIC: A good research objective should be practical and grounded in reality, aligning with what is feasible. Researchers must consider real-world constraints and avoid setting unattainable targets.

T – TIME-BOUND: The objective should have a defined timeframe for completion. Establishing a deadline helps researchers maintain focus and ensures the study progresses efficiently and effectively.

Types of Research Objectives

Research objectives can be broadly classified into two main types:

General Objectives

General objectives represent the overarching, broad goals that the research aims to accomplish.

They articulate what the researcher broadly intends to achieve through the study, providing a ‘big-picture’ perspective of the research intent.

These objectives are less detailed and do not specify the precise steps to be taken, instead, they define the overall direction and purpose of the research endeavor.

Example: For a nursing study on patient satisfaction, a general objective could be: “To understand the factors that influence patient satisfaction within a hospital setting.”

Specific Objectives

Specific objectives are short-term, narrowly focused goals that contribute to achieving the broader general objective.

They are derived from the general objective and break it down into smaller, more manageable, and logically connected components.

Achieving the stated specific objectives ultimately leads to the fulfillment of the overarching general objective.

Specific objectives clearly delineate the researcher’s actions within the study, specifying what will be done, where it will be conducted, and the precise purpose it serves.

They offer a more detailed and focused approach, guiding the practical execution of the research.

Example: Continuing from the general objective above, specific objectives could be:

“To conduct structured interviews with patients to gather detailed feedback on their experiences during their hospital stay.”

“To analyze patient survey data to identify recurring themes and patterns related to factors impacting satisfaction levels.”

“To compare patient satisfaction scores across different departments within the hospital to identify areas for improvement.”

In this example, the specific objectives provide actionable steps for data collection and analysis. Successfully meeting these specific objectives will collectively contribute to achieving the broader general objective of understanding patient satisfaction factors.

In summary, general objectives provide the overall research direction, while specific objectives break down the research process into smaller, achievable, and guide the researcher in realizing the broader research goal.

How to State Objectives Effectively

When formulating research objectives, consider the following guidelines:

Brevity and Conciseness: Objectives should be presented in a brief and to-the-point manner.

Comprehensive Coverage: Objectives should encompass the different aspects of the research problem and related contributing factors in a coherent and logically sequenced manner.

Operational Terms: Objectives must be clearly phrased using operational terms, explicitly stating what the researcher will do, where, and for what purpose.

Realistic Scope: Objectives should be realistic and achievable, considering the specific local context and available resources.

Action Verbs: Objectives should utilize action verbs that are sufficiently specific to allow for evaluation of achievement.

Examples of Action Verbs for Objectives

Action Verbs for Defining Objectives:

Define: To clearly state the meaning of a term or concept.

Identify: To point out or name specific items or factors.

Label: To assign a descriptive name or term to something.

List: To enumerate items in a structured format.

Name: To specify or give the designation of something.

State: To express something clearly and definitely.

Outline: To present the main features or parts in a structured way.

Point out: To direct attention to something specific.

Quote: To cite or repeat words from a source.

Recite: To repeat something from memory.

Recognize: To identify something previously known or encountered.

Match: To pair corresponding items or concepts.

Select: To choose specific items from a group.

Action Verbs for Descriptive Objectives:

Describe: To give a detailed account of something, including its characteristics or features.

Draw: To create a visual representation or diagram.

Record: To document or note down information systematically.

Read: To examine and understand written material.

Broad and Specific Objectives Example:

Research Topic: Risk Factors for Diarrheal Diseases Among Children Below 1 Year

In this example, the broad objective and specific objectives are structured as follows:

Broad Objective: This represents the overarching, primary goal of the research. In this instance, the broad objective is:

“To identify the key risk factors associated with diarrheal diseases in children under the age of one year.”

Specific Objectives: These are the more detailed, targeted goals that contribute to achieving the broad objective. For this example, relevant specific objectives could be:

“To conduct a review of existing scholarly literature on diarrheal diseases in children under one year to pinpoint commonly reported risk factors.”

“To gather data through questionnaires and structured interviews with parents or primary caregivers of children under one year to assess their knowledge and typical practices related to hygiene and sanitation.”

“To analyze the collected data to determine if there is a statistically significant association between specific potential risk factors (such as breastfeeding practices, source of drinking water, and sanitation conditions) and the occurrence of diarrheal diseases in children under one year of age.”

In this scenario, the specific objectives provide a clear roadmap of the research activities needed to accomplish the broader aim of identifying risk factors for diarrheal diseases in young children. Each specific objective is designed to contribute a distinct piece of information that, when combined, will fulfill the overall research objective.

Join Our WhatsApp Groups!

Are you a nursing or midwifery student looking for a space to connect, ask questions, share notes, and learn from peers?

Join our WhatsApp discussion groups today!

Join NowRelated Topics

- Introduction to Research

- Key Terminologies in Research

- Research Ethics

- Purpose of Studying Research

- Research Approaches: Qualitative and Quantitative Methods

- Steps in Research Process

- Formulation of research topics

- Writing a research proposal

- Preliminary Pages

- Chapter One: Introduction

- Chapter Two: Literature review

- Chapter Three: Methodology

- Research Designs/Study Design

- Study Population & Sampling

- Sample Size Determination

- Research Instruments and Research Methods

- References/Referencing

- Appendices & Consent Form

- Chapter Four: Results

- Chapter Five: Discussion, Conclusion and Recommendations

- Research report

Get in Touch

(+256) 790 036 252

(+256) 748 324 644

Info@nursesonlinediscussion.com

Kampala ,Uganda

© 2025 Nurses online discussion. All Rights Reserved Design & Developed by Opensigma.co