Mental Health Disorders in Children

Subtopic:

Eating disorders

Eating disorders are a group of mental health conditions defined by serious irregularities in eating behaviors.

Alternatively stated, eating disorders are significant mental illnesses characterized by disrupted thought patterns and actions related to food, eating habits, and concerns about body weight or shape. These are not simply about food, but reflect deeper psychological and emotional issues.

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), published by the American Psychiatric Association (2013), outlines several patterns of disordered eating. While DSM-5 lists six, four types are most commonly diagnosed in clinical practice:

Anorexia Nervosa (AN)

Bulimia Nervosa (BN)

Binge Eating Disorder (BED)

Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder (ARFID)

In addition to these, the DSM-5 also recognizes two other categories:

Other Specified Feeding or Eating Disorder (OSFED)

OSFED is also considered a clinically significant illness, encompassing eating disorders that cause distress and impairment but do not fully meet the strict diagnostic criteria for Anorexia Nervosa or Bulimia Nervosa. It is important to note that OSFED can be as severe and pose similar health risks as AN or BN.

Unspecified Feeding or Eating Disorder (USFED)

USFED is used when disordered eating behaviors cause notable distress or impair daily functioning, but the full criteria for any specific eating disorder are not met. This category acknowledges clinically relevant eating problems that may not fit neatly into other diagnoses but still require attention and care.

ANOREXIA NERVOSA

Anorexia Nervosa (AN) is a serious eating disorder characterized by a distorted perception of body weight and shape. This distorted body image drives individuals to:

Restrict food intake severely, leading to significantly low body weight.

Engage in excessive exercise beyond what is healthy or necessary.

Exhibit other behaviors aimed at preventing weight gain or actively losing weight, even when underweight.

In other words, Anorexia Nervosa is defined by self-imposed starvation. This starvation is not due to a lack of hunger, but rather stems from an intense fear of gaining weight and becoming fat.

Critically, individuals with Anorexia Nervosa often continue to experience hunger, yet they persistently deny themselves adequate food intake due to their overwhelming fear and distorted body image.

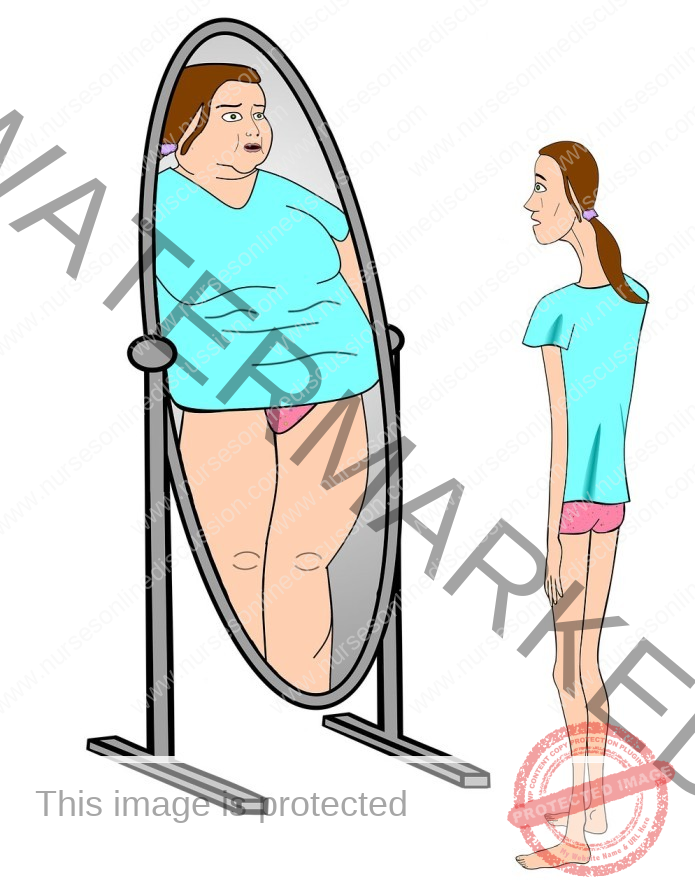

Children and teenagers with anorexia nervosa have a distorted perception of their body image. This distorted self-view leads them to:

See themselves as overweight, even when significantly underweight.

Develop an intense obsession with thinness.

Refuse to maintain even the minimum healthy body weight for their age and height.

Signs and Symptoms of Anorexia Nervosa:

Anorexia Nervosa is characterized by a cluster of specific signs and symptoms, including:

Refusal to Maintain Healthy Weight: Persistent inability or unwillingness to maintain a body weight at or above a minimally normal level for their age and height, often defined as being 85% or less of expected weight.

Intense Fear of Weight Gain: Overwhelming and irrational fear of gaining weight or becoming fat, even when underweight.

Body Image Disturbance: Significant distortion in the way one’s body weight or shape is experienced. This includes:

Feeling “fat” or overweight despite being underweight.

Undue influence of body weight or shape on self-evaluation and self-esteem.

Denial of the seriousness of current low body weight and its potential health consequences.

Dieting Despite Being Underweight: Engaging in persistent dieting behaviors, even when already thin or emaciated, in a relentless pursuit of further weight loss.

Restricted Eating Patterns: Individuals with anorexia nervosa typically:

Maintain a body weight significantly below the minimally normal level for their age, sex, developmental trajectory, and physical health.

Restrict Dietary Intake: Severely limit the types and amounts of food consumed, often excluding foods they perceive as “high-calorie” or fattening.

Purging Behaviors: Some individuals with anorexia nervosa may engage in compensatory behaviors to further control weight, such as:

Self-Induced Vomiting: Intentionally vomiting after eating to eliminate calories.

Misuse of Laxatives, Diuretics, or Enemas: Abusing these substances in an attempt to purge calories or fluids from the body.

Excessive Exercise: Engaging in excessive physical activity to burn calories and promote weight loss, often to a point that is detrimental to health.

Reduced Food Intake: Overall reduction in the total amount of food consumed, often to severely inadequate levels.

Fear of Obesity: Intense and persistent fear of becoming obese or gaining weight, even when objectively underweight.

Picky Eating Habits: Exhibiting strange or unusual eating habits, often becoming extremely selective or “picky” about food choices and preparation.

Menstrual Irregularities (Females): Hormonal imbalances and weight loss can lead to:

Amenorrhea: Absence of menstruation (periods) in females.

Oligomenorrhea: Infrequent or irregular menstrual cycles.

Delayed Menarche: Failure to reach menarche (first menstruation) in adolescents. These menstrual disturbances are linked to reduced estrogen levels and overall weight loss.

Loss of Sexual Interest: Decreased libido or loss of interest in sexual activity due to physical and psychological effects of starvation and malnutrition.

Psychological and Emotional Symptoms: Anorexia nervosa is often accompanied by:

Anxiety: Elevated levels of anxiety, particularly related to food, eating, and body weight.

Depression: Depressed mood, feelings of sadness, hopelessness, and loss of interest in activities.

Perfectionism: Tendency towards perfectionistic thinking and behavior, holding themselves to unrealistically high standards and experiencing intense self-criticism.

Possible Complications of Anorexia Nervosa:

Anorexia Nervosa is a life-threatening condition with severe physical and psychological complications. It has a high mortality rate, with approximately 10% of cases proving fatal. The most common causes of death related to anorexia nervosa include:

Cardiac Arrest: Sudden and unexpected cessation of heart function, often due to severe electrolyte imbalances and cardiac muscle damage.

Electrolyte Imbalance: Dangerous disruptions in the balance of essential electrolytes (sodium, potassium, calcium, etc.) in the body, which can lead to cardiac arrhythmias and organ dysfunction.

Suicide: Increased risk of suicide due to severe depression, hopelessness, and psychological distress associated with the disorder.

Other serious complications of anorexia nervosa include:

Heart Muscle Damage: Malnutrition and repeated vomiting can severely weaken and damage the heart muscle (cardiomyopathy), leading to life-threatening cardiac dysfunction.

Cardiac Arrhythmias: Disrupted heart rhythm, which can manifest as:

Tachycardia: Abnormally fast heartbeat.

Bradycardia: Abnormally slow heartbeat.

Irregular Heartbeat: Erratic or inconsistent heart rhythm, increasing risk of cardiac arrest.

Hypotension: Abnormally low blood pressure, which can cause dizziness, fainting, and reduced blood flow to vital organs.

Electrolyte Imbalance: Severe disruptions in electrolyte balance, leading to a range of symptoms including muscle weakness, seizures, cardiac problems, and neurological dysfunction.

Anemia: Reduced red blood cell count, leading to fatigue, weakness, and impaired oxygen-carrying capacity.

Leukopenia: Reduced white blood cell count, increasing susceptibility to infections and compromising immune function.

Gastrointestinal (GIT) Disturbances: Disruption of normal digestive function, resulting in:

Constipation

Bloating

Abdominal pain

Delayed gastric emptying

Dehydration: Severe fluid loss due to restricted fluid intake, purging behaviors, and metabolic imbalances, leading to electrolyte abnormalities, kidney problems, and organ stress.

Refeeding Syndrome: A potentially fatal condition that can occur when nutrition is reintroduced too rapidly after a period of starvation or severe malnutrition.

Refeeding Syndrome Definition: Refeeding syndrome is characterized by dangerous shifts in electrolytes and fluid balance as the body attempts to adjust to increased nutritional intake after prolonged nutritional deprivation.

Refeeding syndrome requires careful medical monitoring and gradual reintroduction of nutrition to prevent potentially life-threatening complications.

Management or Treatment of Anorexia Nervosa

(Refer to General Management Principles for Eating Disorders)

The primary objective in treating anorexia nervosa is to restore the individual to a healthy weight and normalize eating patterns.

Hospitalization: Inpatient hospitalization, sometimes for several weeks or longer, may be medically necessary for individuals with severe anorexia nervosa. Hospitalization is often required in cases of:

Extreme Malnutrition: Severe underweight and nutritional deficiencies posing immediate health risks.

Life-Threatening Medical Instability: Medical complications such as cardiac instability, electrolyte imbalances, or dehydration.

Tube or Intravenous Feeding: In extreme cases, when oral intake is insufficient or medically contraindicated, nutritional rehabilitation may require:

Nasogastric Tube Feeding: Delivery of liquid nutrition directly into the stomach via a tube inserted through the nose.

Intravenous (IV) Feeding: Providing nutrients and fluids directly into the bloodstream through an IV line.

Nursing Care for Anorexia Nervosa:

Nursing care focuses on both short-term medical stabilization and long-term psychological and behavioral interventions.

Short-Term Management (Weight Restoration and Nutritional Correction):

Weight Gain Focus: Short-term care prioritizes achieving safe and gradual weight gain and correcting life-threatening nutritional deficiencies and medical complications.

Balanced High-Calorie Diet: Provide a structured and balanced diet plan, typically aiming for a high-calorie intake of at least 3000 calories per day to promote weight restoration.

Supervised Meals: Nurses must provide direct supervision during all meals to ensure adherence to the meal plan, prevent calorie restriction or food avoidance, and monitor for any purging behaviors.

Bed Rest and Observation: Initially, patients may require complete bed rest under close nursing observation to:

Minimize Energy Expenditure: Reduce physical activity to conserve energy and promote weight gain.

Achieve Weight Gain Goals: Support the weight gain target of 0.5 to 1 kg (1-2 pounds) per week.

Vomiting Control Measures: Implement measures to control and prevent purging behaviors, such as:

Bathroom Inaccessibility: Restricting access to bathrooms for a specified period (e.g., 2 hours) after meals to prevent self-induced vomiting.

Close Monitoring: Maintaining close observation of the patient to detect and prevent any purging attempts.

Gavage Feeding (Severe Cases): In extreme cases where the patient actively refuses to eat and is severely malnourished, gavage feeding (nasogastric tube feeding) may become medically necessary to provide life-sustaining nutrition against the patient’s will. This intervention is typically used as a last resort in situations of imminent medical danger.

Weight Monitoring: Regularly monitor and document the patient’s weight, typically daily or several times per week, and meticulously plot weight changes on a weight chart to track progress and guide nutritional adjustments.

Intake and Output Chart: Maintain a strict and accurate intake and output (I&O) chart to monitor fluid balance, nutritional intake, and any fluid losses (e.g., through vomiting or purging).

Dehydration Assessment: Regularly assess skin turgor, mucous membrane moisture, and other clinical indicators to monitor for signs of dehydration and electrolyte imbalances.

Emotional Support and Verbalization Encouragement:

Verbalization of Feelings: Encourage the patient to verbalize and express their feelings, anxieties, and fears related to weight gain, body image, and the eating disorder.

Therapeutic Communication: Utilize therapeutic communication techniques to build trust, provide emotional support, and validate the patient’s emotional experiences.

Family Involvement in Education: Actively involve the patient’s family in education sessions to:

Educate Family on Anorexia Nervosa: Provide comprehensive education to family members about the nature of anorexia nervosa, its causes, symptoms, and treatment approaches.

Family Support Strategies: Equip families with strategies to effectively support the patient’s recovery, promote healthy eating patterns, and foster a supportive home environment.

Avoid Food and Weight Focus in Discussions: During therapeutic interactions, avoid excessive focus or direct discussions centered on food, weight, or body shape, as these topics can be triggering and counterproductive in the early stages of recovery. Focus instead on emotional well-being, coping skills, and underlying psychological issues.

Long-Term Treatment (Addressing Psychological Issues):

Long-term treatment for anorexia nervosa focuses on addressing the underlying psychological and emotional issues that drive the disorder and preventing relapse. This comprehensive approach typically includes:

Antidepressant Medications: Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and other antidepressants may be prescribed to address co-occurring depression, anxiety, or obsessive-compulsive symptoms, which are common in anorexia nervosa.

Neuroleptics (Antipsychotics): In some cases, low doses of neuroleptic medications may be used to manage distorted thinking, body image disturbances, or severe anxiety, particularly in individuals with psychotic features or severe agitation.

Appetite Stimulants: While less commonly used, certain appetite stimulants may be considered in some cases to help increase appetite and promote weight gain, although their effectiveness in anorexia nervosa is limited.

Behavioral Therapy: Behavioral therapy techniques, such as Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) or Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT), may be used to:

Modify Maladaptive Eating Behaviors: Help patients identify and change unhealthy eating patterns and compensatory behaviors (purging, excessive exercise).

Develop Healthier Coping Mechanisms: Teach adaptive coping skills to manage emotions, stress, and triggers that contribute to disordered eating.

Individual Therapy: Individual psychotherapy is a cornerstone of long-term treatment, providing a safe space for patients to:

Explore Underlying Psychological Issues: Address core psychological issues, emotional conflicts, and distorted beliefs that contribute to the eating disorder.

Improve Self-Esteem and Body Image: Work on improving self-esteem, body image distortions, and negative self-perceptions.

Develop Coping Strategies: Develop healthier coping mechanisms for managing emotions, stress, and interpersonal challenges.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT): Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) is a widely used and evidence-based therapy for eating disorders, focusing on:

Identifying and Challenging Negative Thoughts: Helping patients identify and challenge negative, distorted thoughts and beliefs related to food, weight, and body image.

Modifying Unhelpful Behaviors: Changing maladaptive eating behaviors, restrictive patterns, and compensatory behaviors.

Developing Cognitive and Behavioral Skills: Teaching cognitive restructuring techniques and behavioral strategies to manage eating disorder symptoms and improve emotional regulation.

Family Therapy: Family therapy is often essential, particularly for adolescents with anorexia nervosa, involving family members in the treatment process to:

Improve Family Communication: Enhance communication patterns and reduce conflict within the family system.

Address Family Dynamics: Address family dynamics and patterns of interaction that may contribute to or maintain the eating disorder.

Support Patient Recovery: Equip family members with the knowledge and skills to effectively support the patient’s recovery and create a supportive home environment.

Psychotherapy: Broader psychotherapeutic approaches may be used to address deeper emotional and psychological issues, including:

Psychodynamic Therapy: Exploring unconscious conflicts, early childhood experiences, and relational patterns that may contribute to the eating disorder.

Interpersonal Therapy (IPT): Focusing on improving interpersonal relationships, communication skills, and social functioning.

Support Groups: Participation in support groups can provide valuable peer support, reduce feelings of isolation, and offer a sense of community among individuals with eating disorders.

BULIMIA NERVOSA

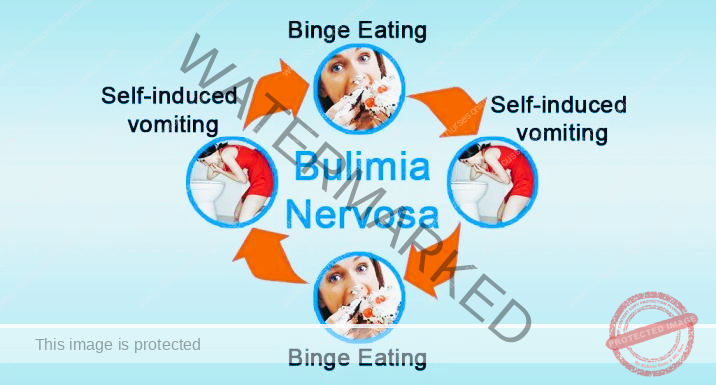

Bulimia Nervosa, commonly referred to as Bulimia, is another distinct type of eating disorder characterized by a cyclical pattern of behaviors involving:

Binge Eating Episodes: Recurrent episodes of bingeing, defined as consuming an unusually large amount of food in a short period, accompanied by a sense of loss of control over eating during the episode.

Compensatory Behaviors (Purging): Engaging in recurrent inappropriate compensatory behaviors to counteract the effects of binge eating and prevent weight gain. These behaviors are commonly referred to as purging and may include:

Self-Induced Vomiting: Intentionally vomiting after binge eating to eliminate calories.

Misuse of Laxatives: Abusing laxatives in an attempt to purge calories or accelerate food passage through the digestive system.

Misuse of Diuretics: Abusing diuretics to reduce fluid retention and manipulate weight.

Misuse of Enemas: Using enemas to eliminate calories or control weight.

Excessive Exercise: Engaging in extreme or compulsive exercise as a compensatory measure.

Fasting: Periods of strict calorie restriction or fasting following binge episodes.

In essence, Bulimia Nervosa is a syndrome characterized by recurrent episodes of binge eating followed by compensatory or purging behaviors, driven by an excessive preoccupation with body weight and shape.

Individuals with bulimia nervosa engage in these compensatory behaviors in an attempt to prevent weight gain after binge eating episodes. They may use:

Self-Induced Vomiting

Laxatives

Diet Pills

Diuretics

Enemas

After engaging in purging behaviors, individuals with bulimia often experience a temporary sense of relief from the anxiety and guilt associated with binge eating and fear of weight gain.

Binge eating episodes in bulimia are frequently performed in private, often accompanied by feelings of shame and secrecy.

Notably, individuals with bulimia nervosa are often within a normal weight range or may even be slightly overweight. This can make the disorder less readily apparent to others, as outward physical signs may not be as obvious as in anorexia nervosa.

Bulimia Nervosa typically emerges in late adolescence or early adulthood, and it is diagnosed predominantly in women, although it can affect individuals of all genders.

Co-occurring mental health issues are common in individuals with bulimia nervosa, including:

Depression

Anxiety Disorders

Substance Use Disorders (Drug or Alcohol Abuse)

Self-Injurious Behaviors

Doctors typically establish a diagnosis of Bulimia Nervosa when an individual engages in binge eating and inappropriate compensatory behaviors at least twice a week for a duration of three months or more.

Individuals with bulimia nervosa often experience fluctuations in weight that remain within a normal range, although some may be overweight or obese. It is estimated that as many as 1 in 25 females will experience bulimia nervosa at some point in their lifetime, highlighting its significant prevalence, particularly among women.

Binge Eating Defined:

Binge eating is a core feature of bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder. It is characterized by:

Eating Large Amounts of Food: Consuming an objectively large quantity of food within a discrete period of time (e.g., within any 2-hour period).

Sense of Lack of Control: Experiencing a subjective sense of loss of control over eating during the episode, feeling unable to stop eating or control the amount or type of food consumed.

“Larger Than Normal” Amount: The amount of food consumed during a binge is considered definitively larger than what most individuals would typically eat in a similar timeframe and under similar circumstances.

Individuals with Bulimia Nervosa typically experience significant shame and guilt related to their eating disorder symptoms.

Signs and Symptoms of Bulimia Nervosa:

Bulimia Nervosa is characterized by a pattern of binge eating followed by compensatory behaviors, accompanied by specific signs and symptoms:

Shame and Secrecy: Individuals with bulimia often feel deeply ashamed of their eating behaviors and tend to conceal their symptoms from others, engaging in binge eating and purging in secrecy.

Physical Symptoms Related to Purging: Chronic purging behaviors, particularly self-induced vomiting, can lead to various physical signs and symptoms:

Persistent Heartburn: Acid reflux and irritation of the esophagus due to frequent vomiting.

Sore Throat: Irritation and inflammation of the throat from repeated vomiting.

Abdominal Pain: Discomfort or pain in the abdominal region.

Epigastric Pain: Pain localized to the upper central abdomen, often associated with stomach irritation.

Rapid Food Consumption During Binges: During binge eating episodes, food is typically consumed at an accelerated pace, often characterized by:

Eating Quickly: Rapidly consuming large quantities of food in a short period.

Loss of Control: Feeling unable to control the amount or pace of eating during the binge.

Eating to Discomfort or Pain: Binge eating episodes often continue until the individual experiences physical discomfort or even painful fullness due to overconsumption.

Triggers for Binge Eating: Binge eating episodes are frequently triggered by:

Low Mood: Feelings of sadness, depression, or emotional distress.

Interpersonal Stressors: Stressful events or conflicts in relationships with others.

Intense Hunger Following Dietary Restraint: Paradoxical binge eating triggered by attempts at strict dieting or calorie restriction, leading to rebound overeating.

Loss of Control During Bingeing: A defining feature of bulimia nervosa is the subjective loss of control over eating during binge episodes. This includes:

Difficulty Resisting Binge Eating: Feeling unable to resist the urge to binge eat.

Difficulty Stopping Binge Eating: Feeling unable to stop eating once a binge episode has begun, despite a desire to do so.

Compensatory Techniques (Purging): Individuals with bulimia nervosa engage in various compensatory techniques to counteract the perceived effects of binge eating and prevent weight gain. The most common compensatory behavior is:

Self-Induced Vomiting: Intentionally vomiting after binge eating as a means of purging calories.

Emphasis on Body Shape and Weight: An excessive focus on body weight and shape significantly influences self-evaluation and self-esteem. Individuals with bulimia nervosa:

Place Undue Importance on Weight and Shape: Their self-worth and self-image are heavily contingent on their perceived body weight and shape.

Fear of Weight Gain: Despite engaging in compensatory behaviors, individuals with bulimia nervosa often experience a persistent and intense fear of gaining weight.

Weight Fluctuations: Individuals with bulimia nervosa typically experience:

Normal Weight Range: Often maintain a body weight within the normal range for their age and height.

Overweight: Some individuals may be overweight, while others may be underweight.

Weight Fluctuations: Weight may fluctuate within or outside the normal range due to the cyclical nature of binge eating and purging.

Low Self-Esteem: Bulimia nervosa is often associated with low self-esteem and negative self-perception, particularly related to body image and eating behaviors.

Increased Anxiety: Individuals with bulimia nervosa may experience heightened levels of anxiety, including:

Social Anxiety: Increased anxiety and discomfort in social situations, often related to body image concerns or fear of judgment about eating behaviors.

Fluid and Electrolyte Imbalance: Frequent purging behaviors, especially self-induced vomiting and laxative abuse, can lead to dangerous:

Fluid Imbalances: Dehydration and disruptions in fluid balance within the body.

Electrolyte Imbalances: Significant imbalances in essential electrolytes (potassium, sodium, chloride, etc.), which can have serious medical consequences, including cardiac arrhythmias and muscle weakness.

Menstrual Irregularities (Females): Hormonal imbalances and nutritional disturbances can contribute to:

Menstrual Irregularity: Irregular or unpredictable menstrual cycles.

Amenorrhea: Absence of menstruation (periods) in females.

Rectal Prolapse: Chronic laxative abuse, straining during bowel movements, and fluid/electrolyte imbalances can, in severe cases, lead to rectal prolapse, a condition where the rectum protrudes from the anus.

Increased Dental Caries (Tooth Decay): Frequent vomiting exposes teeth to stomach acid, eroding tooth enamel and significantly increasing the risk of dental cavities and tooth decay.

Scarring of Knuckles (Russell’s Sign): Repeated self-induced vomiting can cause characteristic scarring or calluses on the knuckles of the hand used to stimulate the gag reflex, known as Russell’s sign.

Management or Treatment of Bulimia Nervosa

(Refer to General Management Principles for Eating Disorders)

The primary goal of bulimia nervosa treatment is to break the destructive binge-and-purge cycle and restore healthy eating behaviors. Treatment approaches typically involve a combination of therapies and interventions, including:

Nursing Care for Bulimia Nervosa:

Nursing care focuses on establishing a therapeutic relationship, promoting healthy eating patterns, and addressing psychological and behavioral issues:

Therapeutic Alliance: Prioritize building a strong therapeutic alliance with the patient, establishing trust, rapport, and open communication. A strong therapeutic relationship is essential for:

Gaining Patient Commitment: Eliciting the patient’s genuine commitment to engaging in treatment and working towards recovery.

Meal Contracts: Establish clear and structured meal contracts with the patient to normalize eating patterns. This may involve:

Specifying Food Amount and Type: Defining the specific amount and types of food the patient must consume at each meal to ensure adequate nutritional intake.

Setting Time Limits for Meals: Establishing reasonable time limits for meal completion to encourage mindful eating and prevent prolonged meal rituals.

Elimination Pattern Identification: Assess and document the patient’s typical elimination patterns (bowel movements, urination) to monitor for any irregularities or complications related to purging behaviors.

Emotional Verbalization Encouragement: Encourage the patient to recognize, identify, and verbalize their feelings and emotions related to their eating behaviors, body image concerns, and underlying psychological distress.

Purging Risk Education: Provide clear and direct education to the patient about the serious risks and medical consequences associated with laxative, emetic (vomiting-inducing), and diuretic abuse, emphasizing the potential for long-term health damage.

Suicide Risk Assessment and Monitoring: Routinely assess and closely monitor the patient’s suicide potential, as individuals with bulimia nervosa, particularly those with co-occurring depression or other mental health conditions, may be at increased risk of suicidal ideation or attempts. Implement appropriate safety precautions and crisis intervention strategies as needed.

Other Treatment Modalities for Bulimia Nervosa:

In addition to nursing care, comprehensive bulimia nervosa treatment typically involves a combination of the following modalities:

Antidepressant Medication: Antidepressant medications, particularly Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs), are often prescribed to help reduce binge-purge cycles, manage co-occurring depression or anxiety, and improve overall mood regulation.

Behavior Modification Therapy: Behavioral therapy techniques aim to:

Break Binge-Purge Cycle: Disrupt and interrupt the cyclical pattern of binge eating and compensatory behaviors.

Establish Healthy Eating Patterns: Help patients develop and maintain regular, balanced eating habits and normalize their relationship with food.

Individual, Family, or Group Therapy: Various forms of psychotherapy are crucial for addressing the underlying psychological and emotional factors driving bulimia nervosa:

Individual Therapy: Provides a safe space for patients to explore personal issues, improve self-esteem, and develop coping mechanisms.

Family Therapy: Involves family members in the treatment process to improve communication, address family dynamics that may contribute to the disorder, and build a supportive home environment.

Group Therapy: Offers peer support, reduces feelings of isolation, and provides a platform for sharing experiences and coping strategies with others facing similar challenges.

Nutritional Counseling: Registered dietitians or nutritionists provide specialized nutritional counseling to:

Normalize Eating Patterns: Develop balanced meal plans and normalize eating habits, addressing food restrictions and distorted eating patterns.

Educate on Healthy Nutrition: Provide education on healthy nutrition, balanced diets, and the importance of adequate calorie intake and nutrient balance.

Address Food Misconceptions: Challenge and correct misinformation and distorted beliefs about food, calories, and weight management.

Self-Help Groups: Encourage participation in self-help groups or support organizations, such as Overeaters Anonymous, to provide ongoing peer support and connection with others in recovery.

Complications of Bulimia Nervosa:

Chronic binge eating and purging behaviors in bulimia nervosa can lead to a range of serious medical complications:

Dental Damage: Stomach acid exposure from chronic vomiting erodes tooth enamel, causing significant:

Tooth Enamel Erosion: Wearing away of the protective outer layer of teeth.

Increased Dental Caries: Higher risk of cavities, tooth decay, and dental problems.

Esophageal Inflammation: Repeated vomiting irritates and inflames the esophagus (the tube connecting the mouth to the stomach), leading to:

Esophagitis: Inflammation of the esophageal lining, causing pain, heartburn, and swallowing difficulties.

Salivary Gland Swelling: Frequent vomiting can cause enlargement and swelling of the salivary glands in the cheeks, resulting in visible swelling and discomfort.

Hypokalemia (Low Potassium): Purging behaviors, particularly vomiting and laxative abuse, can lead to significant potassium loss, resulting in hypokalemia, a dangerously low potassium level in the blood. Hypokalemia can cause:

Abnormal Heart Rhythms (Arrhythmias): Disruption of normal heart rhythm, potentially leading to life-threatening cardiac events and sudden cardiac arrest.

BINGE EATING DISORDER (BED)

Binge Eating Disorder (BED) shares some similarities with bulimia nervosa but is distinguished by the absence of regular compensatory or purging behaviors.

Binge eating in BED is characterized by:

Chronic, Out-of-Control Eating: Recurrent episodes of binge eating, marked by a persistent pattern of consuming unusually large amounts of food with a sense of loss of control.

Large Food Quantities: Eating objectively large amounts of food in a discrete period of time (e.g., within a 2-hour period), exceeding what most people would eat in similar circumstances.

Eating to Discomfort: Binge eating episodes often continue until the individual feels uncomfortably full, even to the point of physical discomfort.

Secrecy and Shame: Binge eating is frequently done in secret and is often accompanied by feelings of embarrassment, shame, and guilt about the quantity of food consumed and the lack of control over eating.

Absence of Purging: Unlike bulimia nervosa, individuals with BED do not regularly engage in compensatory behaviors such as self-induced vomiting, laxative abuse, or excessive exercise to counteract the effects of binge eating.

Individuals with Binge Eating Disorder:

Eat Large Amounts Secretly: Often consume unusually large quantities of food when alone or in secret, due to shame and embarrassment about their eating behavior.

Lack Calorie Compensation: Do not attempt to get rid of the excess calories consumed during binges through purging or other compensatory methods.

Weight Range Variability: Individuals with BED can be within a normal weight range, overweight, or obese. However, BED is strongly associated with overweight and obesity due to the recurrent consumption of large amounts of food without compensatory calorie burning.

Psychological Distress: May experience significant psychological distress, including:

Depression

Anxiety

Shame and Guilt related to their binge eating behaviors.

Coping Difficulties: Many individuals with BED struggle with emotional regulation and may use binge eating as a maladaptive coping mechanism to manage:

Anger

Sadness

Boredom

Worry

Stress

Symptoms of Binge Eating Disorder:

Binge Eating Disorder often lacks overt physical symptoms directly related to the eating disorder itself. However, it is characterized by significant psychological symptoms that may or may not be readily apparent to others. These include:

Psychological Symptoms:

Depression

Anxiety

Shame and Guilt: Intense feelings of shame, guilt, and self-disgust related to the amount of food consumed and loss of control during binges.

Behavioral Symptoms:

Frequent Dieting Without Weight Loss: Engaging in repeated attempts to diet or restrict calorie intake, often without achieving sustained weight loss, reflecting a struggle with weight management and eating control.

Health Risks Associated with Binge Eating Disorder:

The excess weight gain and metabolic consequences of recurrent binge eating significantly increase the risk of developing various health problems, including:

Cardiovascular Disease: Increased risk of heart disease and related cardiovascular complications.

Hypertension (High Blood Pressure): Elevated blood pressure, increasing risk of heart disease and stroke.

Hypercholesterolemia (High Cholesterol): Elevated cholesterol levels, contributing to heart disease risk.

Type 2 Diabetes: Increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes due to insulin resistance and weight gain.

Treatments for Binge Eating Disorder:

Treatment approaches for Binge Eating Disorder aim to reduce binge eating episodes, promote healthier eating patterns, and address underlying psychological and emotional factors. These treatments typically include:

(Refer to General Management Principles for Eating Disorders)

Behavioral Therapy: Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) and other behavioral therapies are often first-line treatments, focusing on:

Reducing Binge Eating Episodes: Developing strategies to manage triggers, cravings, and emotional factors that contribute to binge eating.

Establishing Healthy Eating Habits: Promoting regular, balanced eating patterns and normalizing food intake.

Medications: Certain medications may be used in conjunction with therapy, including:

Antidepressants: To address co-occurring depression or anxiety symptoms.

Appetite Suppressants: In some cases, medications to help reduce appetite and cravings may be considered, although their long-term effectiveness for BED is still under investigation.

Psychotherapy: Individual or group psychotherapy can help patients:

Address Underlying Emotional Issues: Explore and address underlying psychological and emotional factors that contribute to binge eating, such as emotional distress, low self-esteem, or body image concerns.

Develop Coping Mechanisms: Learn healthier coping strategies for managing emotions, stress, and triggers without resorting to binge eating.

AVOIDANT/RESTRICTIVE FOOD INTAKE DISORDER (ARFID)

Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder (ARFID) is a distinct eating disorder characterized by:

Avoidance or Restriction of Food Intake: Individuals with ARFID exhibit a persistent pattern of disturbed eating characterized by:

Limiting Food Types: Restricting the variety of foods consumed, often to a very narrow range of acceptable foods.

Avoiding Certain Foods: Actively avoiding specific foods or entire food groups based on sensory characteristics or perceived aversions.

Restricting Overall Intake: Significantly limiting the total quantity of food consumed, leading to inadequate calorie and nutrient intake.

Sensory Sensitivities and Aversions: Food avoidance or restriction in ARFID is often driven by sensory factors, such as:

Texture: Aversions to specific food textures (e.g., mushy, crunchy, smooth).

Color: Avoidance of foods based on their color (e.g., green vegetables, red fruits).

Taste: Extreme pickiness related to taste preferences, often limited to very bland or specific flavors.

Temperature: Avoidance of foods at certain temperatures (e.g., only eating food that is cold or only food that is hot).

Aroma: Aversions to specific food smells or aromas.

Consequences of ARFID: The restricted eating patterns in ARFID can lead to significant:

Weight Loss: Unintentional and significant weight loss due to inadequate calorie intake.

Inadequate Growth (Children): Impaired growth and development in children and adolescents due to nutritional deficiencies.

Nutritional Deficiencies: Deficiencies in essential vitamins, minerals, and macronutrients due to limited food variety and intake.

Psychosocial Impairment: Difficulties in social situations related to eating, such as an inability to eat with others in social settings, leading to social isolation or anxiety.

Distinction from Anorexia Nervosa: Unlike anorexia nervosa, ARFID is not primarily driven by concerns about body weight or shape or an intense fear of weight gain. Individuals with ARFID:

Lack Body Image Disturbance: Do not exhibit the distorted body image characteristic of anorexia nervosa.

Lack Intentional Weight Loss Motivation: Their food restriction is not primarily motivated by a desire to lose weight or become thin.

Narrow Food Range Example: For instance, a child with ARFID might only consume a very limited range of foods, such as plain pasta, white bread, and a few specific processed snacks, and refuse to eat any other foods, even familiar foods if they appear slightly different or are prepared in a new way.

Onset and Prevalence: ARFID commonly develops in childhood and can persist into adulthood. It can affect individuals of all ages, not just children.

Assessment/Screening for an Eating Disorder

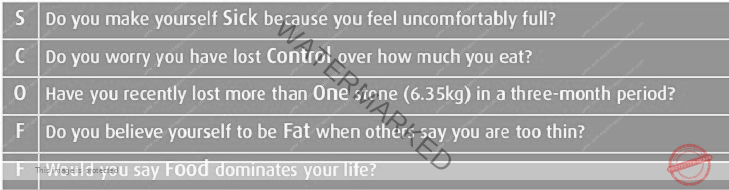

1. The SCOFF Test: A Brief Screening Questionnaire

The SCOFF questionnaire is a brief, five-item screening tool designed for rapid and efficient identification of potential eating disorders, particularly in primary care and non-specialist settings. It was developed by John Morgan at Leeds Partnerships NHS Foundation Trust.

Purpose of SCOFF Test:

Early Detection: To facilitate early detection of eating disorders, particularly Anorexia Nervosa and Bulimia Nervosa, in individuals presenting with unexplained weight loss or other suggestive symptoms.

Improved Prognosis: Early identification and intervention are associated with better treatment outcomes and improved prognosis for eating disorders.

Primary Care Utility: The SCOFF test is designed to be easily administered and interpreted in primary care settings and other non-specialized healthcare environments.

SCOFF Questionnaire Items (Acronym): The SCOFF acronym represents the first letter of each of the five screening questions:

**(S)**ick: Do you make yourself Sick because you feel uncomfortably full?

**(C)**ontrol: Do you worry you have lost Control over how much you eat?

**(O)**ne stone: Have you recently lost more than One stone (14 pounds) in a 3-month period? (This question assesses rapid weight loss)

**(F)**at: Do you believe yourself to be Fat when others say you are too thin? (Assesses body image distortion)

**(F)**ood: Would you say that Food dominates your life? (Assesses the degree of preoccupation with food and eating)

Validation and Effectiveness: The SCOFF questionnaire has been validated for use in both specialist eating disorder settings and primary care environments. Validation studies have demonstrated:

High Sensitivity: Sensitivity of 100% in detecting cases of Anorexia Nervosa, meaning it effectively identifies nearly all true cases of AN.

High Specificity: Specificity of 90%, indicating a low rate of false positives and a good ability to rule out eating disorders in individuals who do not have them.

Interpretation of SCOFF Score:

Positive Screening Threshold: A score of 2 or more positive answers (affirmative responses to two or more SCOFF questions) is considered a positive screening result and should:

Raise Index of Suspicion: Increase clinical suspicion for the presence of an eating disorder.

Warrant Comprehensive Assessment: Indicate the need for a more comprehensive assessment for a potential eating disorder by a qualified healthcare professional.

Specialist Consultation Recommended: Suggest consideration of consultation with an eating disorder expert or mental health clinician for further evaluation and diagnosis.

2. SUSS (Sit-Up – Squat – Stand Test) for Muscle Strength

The Sit-Up – Squat – Stand (SUSS) test is a simple physical assessment used to evaluate a patient’s muscle strength and functional capacity. It consists of two parts:

Sit-Up Test:

Starting Position: The patient lies flat on their back on the floor.

Action: The patient attempts to sit up to a fully upright position.

Assistance: Ideally, the patient should perform the sit-up without using their hands for assistance.

Squat-Stand Test:

Starting Position: The patient stands upright.

Action: The patient squats down to a fully lowered position and then returns to a standing position.

Assistance: Ideally, the patient should perform the squat and stand without using their hands for support.

Scoring for SUSS Test (Separate Scores for Sit-up and Squat-Stand):

The SUSS test is scored separately for both the Sit-up and Squat-Stand components, using the following scale:

| Parameter | Score |

| Unable to perform | 0 |

| Able only with hand assistance | 1 |

| Able with noticeable difficulty | 2 |

| Able with no difficulty | 3 |

RED FLAGS Indicated by SUSS Score:

A Sit up – Squat – Stand (SUSS) score ≤ 2 (for either the sit-up or squat-stand test, or both) is considered a RED FLAG, suggesting potential medical instability in patients with Anorexia Nervosa (AN).

RED FLAGS for Sudden Death Risk in Anorexia Nervosa:

Patients with Anorexia Nervosa exhibiting the following RED FLAGS are at significantly increased risk of sudden death and require immediate medical attention:

SUSS Score ≤ 2: Indicates significant muscle weakness and functional impairment, reflecting severe physical compromise.

Postural Drop: A significant drop in blood pressure upon standing, suggesting cardiovascular instability.

Bradycardia: Abnormally slow heart rate, indicating potential cardiac compromise.

Hypothermia: Abnormally low body temperature, reflecting metabolic dysregulation and severe malnutrition.

Electrolyte Abnormalities: Significant imbalances in electrolytes (e.g., potassium, sodium), posing a high risk of cardiac arrhythmias and other life-threatening complications.

Nurses Role During Assessment (Eating Disorders):

Nurses are critically positioned to play a vital role in the early detection and management of eating disorders. In both hospital and primary care settings, nurses are essential for:

Screening and Detection: Nurses are often the first healthcare professionals to interact with patients and are crucial in:

Screening for eating disorder indicators during routine assessments.

Identifying subtle signs and symptoms that may suggest an underlying eating disorder.

Supporting Psychological Therapies: Nurses are integral to the therapeutic team, playing a supportive role in:

Assisting in the implementation of psychologically-based therapies (e.g., CBT, DBT).

Psycho-education: Providing essential psycho-education to patients and families regarding:

The nature of eating disorders and their medical and psychological consequences.

Risk Assessment: Conducting ongoing assessments to identify and monitor patient risk levels, particularly for medical and psychiatric complications.

Promoting Recovery and Hope: Instilling hope and providing ongoing support and encouragement to patients throughout their recovery journey.

Family and Caretaker Involvement: Facilitating and supporting the active involvement of families and caretakers in the treatment and recovery process.

Co-morbidity Observation: Vigilantly observing for and monitoring co-occurring medical and psychiatric conditions that are frequently present alongside eating disorders.

GENERAL MANAGEMENT OF EATING DISORDERS

Aims of General Management:

The overarching aims of general management for eating disorders are:

Nutritional Restoration: To safely and effectively restore the patient’s nutritional status to a healthy and sustainable level.

Complication Prevention: To prevent and manage both medical and psychological complications associated with eating disorders.

General Management Strategies:

General management principles for eating disorders encompass a comprehensive and multidisciplinary approach:

Therapeutic Relationship Development: Establish a strong trusting relationship with the patient as the foundation for effective treatment.

Positive Regard: Consistently convey positive regard and unconditional acceptance to the patient, fostering a supportive and non-judgmental therapeutic environment.

Supervision and Monitoring (Especially During and After Meals): Provide close supervision and monitoring, particularly:

During Mealtimes: Supervise patients during meals to encourage adequate intake and prevent food avoidance or restriction.

Post-Meal Monitoring: Remain with the patient for at least 1 hour after meals to prevent purging behaviors (e.g., self-induced vomiting).

Avoid Argumentation or Bargaining: When encountering patient resistance to treatment or meal plans, avoid:

Arguing: Engaging in confrontational arguments or power struggles with the patient regarding eating or treatment adherence.

Bargaining: Negotiating or making deals with the patient regarding food intake or treatment goals, as this can undermine therapeutic boundaries.

Fact-Based Communication: Communicate clearly and directly, stating matters of fact regarding:

Unacceptable Behaviors: Clearly identify and communicate which eating disorder behaviors are unacceptable and detrimental to their health (e.g., purging, excessive exercise, calorie restriction).

Emotional Expression Encouragement: Encourage the patient to verbalize and explore their feelings related to:

Family Roles: Exploring perceived or actual role within the family system and any related pressures or conflicts.

Dependence Issues: Addressing issues related to dependence, independence, and autonomy that may be contributing to the eating disorder.

Control and Problem-Solving: Help the patient recognize and develop healthy ways to gain a sense of control over:

Life Problems: Identifying and addressing underlying life stressors, emotional challenges, or interpersonal difficulties that may be contributing to the eating disorder.

Realistic Body Image and Food Relationship: Assist the patient in developing a more realistic and positive perception of their body image and a healthier relationship with food, moving away from distorted beliefs and anxieties.

Environmental Control and Empowerment: Promote a sense of control within the treatment environment by:

Participation in Decision-Making: Involving the patient in appropriate treatment decisions and care planning to foster autonomy and agency.

Daily Weight Monitoring: Weigh the patient daily to track weight changes and monitor progress in weight restoration. Ensure accuracy by:

Consistent Weighing Scale: Always use the same weighing scale for consistent measurements.

Standardized Weighing Protocol: Follow a standardized weighing protocol (e.g., same time of day, same clothing) to minimize variability.

Strict I&O Monitoring: Maintain a strict and accurate record of:

Fluid Intake: All fluids consumed by the patient.

Fluid Output: All fluid losses, including urine output, vomiting, or diarrhea, to monitor fluid balance and hydration status.

Skin and Mucous Membrane Assessment: Regularly assess the patient’s:

Skin Status: Monitor skin turgor, dryness, and signs of dehydration or nutritional deficiencies.

Oral Mucous Membranes: Assess the moistness and color of oral mucous membranes as indicators of hydration and nutritional status.

Behavior Modification:

Collaborative Care Plan: Develop an individualized care plan in collaboration with the patient, ensuring their active participation and input in the treatment process.

Contracting: Utilize behavioral contracts where appropriate to:

Specify Goals: Clearly define specific, measurable, and achievable behavioral goals related to eating and weight restoration.

Outline Rewards: Establish a system of rewards or positive reinforcement that are contingent upon the patient’s progress in meeting agreed-upon goals.

The reward system should be carefully designed and ethically implemented, focusing on positive reinforcement rather than punishment.

Individual Therapy:

Psychotherapy: Individual therapy, particularly psychotherapy approaches, is often crucial for addressing:

Underlying Psychological Problems: Exploring and addressing any underlying psychological issues, emotional conflicts, or trauma that may be contributing to the eating disorder.

Maladaptive Behaviors: Working to modify maladaptive thoughts, feelings, and behaviors related to eating and body image.

Family Therapy:

Family Counseling and Education: Involve family members in the treatment process through family therapy, which aims to:

Counsel Family Members: Provide education, support, and guidance to family members on understanding and responding to the eating disorder effectively.

Educate Family About the Disorder: Increase family members’ knowledge and understanding of anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa, dispelling myths and misconceptions.

Assess Family Perceptions and Attitudes: Evaluate family members’ perceptions, attitudes, and beliefs related to food, weight, body image, and the eating disorder, addressing any potential unhelpful family dynamics.

Family Support: Provide ongoing emotional and practical support to family members, recognizing the significant stress and burden they may experience in supporting a loved one with an eating disorder.

Referral:

Specialized Care: When necessary, ensure timely referral to specialized eating disorder treatment programs, centers, or professionals for more intensive or specialized care, particularly in cases of:

Severe Medical Instability

Treatment Resistance in Outpatient Settings

Complex Co-occurring Conditions

Chemotherapy (Pharmacotherapy):

Medication as Adjunct Therapy: While there are no specific medications that directly “cure” eating disorders, certain medications may be used as adjunctive therapy to address co-occurring conditions or specific symptoms:

Antidepressants (e.g., Fluoxetine): May be used to treat co-morbid depression, anxiety, or obsessive-compulsive features.

Chlorpromazine (Antipsychotic): In some cases, antipsychotic medications may be used to manage severe body image distortion or agitation, particularly in anorexia nervosa.

Lithium Carbonate (Mood Stabilizer): May be considered in some cases, particularly in bulimia nervosa with co-occurring mood instability, although its primary role is not in treating the eating disorder itself.

Appetite Stimulants (Limited Role): Appetite stimulants are generally not a primary treatment for eating disorders and have limited effectiveness in anorexia nervosa.

Nursing Diagnoses (Examples):

Nursing diagnoses for patients with eating disorders will vary based on individual presentations, but common examples include:

Imbalanced Nutrition: Less Than Body Requirements: Related to refusal to eat or self-induced vomiting, as evidenced by weight loss, low body mass index, and reported calorie restriction.

Ineffective Denial: Related to fear of weight gain or distorted ego development, as evidenced by inability to acknowledge the impact of maladaptive eating behaviors on life patterns and health.

Disturbed Body Image: Related to false perception of increased body weight or distorted body size, as evidenced by patient verbalizations of feeling “fat” or overweight despite being underweight, and excessive concern with body shape and weight.

We are a supportive platform dedicated to empowering student nurses and midwives through quality educational resources, career guidance, and a vibrant community. Join us to connect, learn, and grow in your healthcare journey

Quick Links

Our Courses

Legal / Policies

Get in Touch

(+256) 790 036 252

(+256) 748 324 644

Info@nursesonlinediscussion.com

Kampala ,Uganda

© 2025 Nurses online discussion. All Rights Reserved | Design & Developed by Opensigma