Integumentary Disorders of the Skin

Subtopic:

Atopic dermatitis (AD)

Atopic dermatitis (AD), also frequently referred to as atopic eczema, is a prevalent form of eczema characterized by skin that becomes intensely itchy, notably dry, and prone to cracking.

This condition leads to skin that is not only itchy but also exhibits redness, swelling, and fissures. In some instances, the affected areas may weep a clear fluid and tend to thicken over time due to persistent inflammation.

Other terms that may be used to describe atopic dermatitis include:

Infantile eczema

Flexural eczema

Prurigo Besnier

Allergic eczema

Neurodermatitis

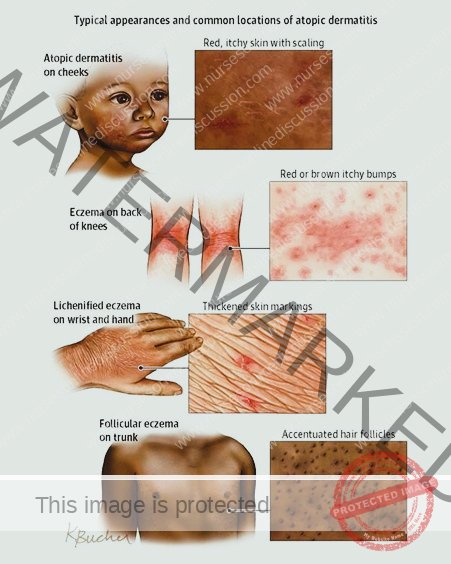

While atopic dermatitis can manifest at any point in life, it typically has its onset during childhood and may fluctuate in severity throughout the years. In infants younger than one year, a significant portion of the body surface may be affected by the condition.

As children age, the areas behind the knees and the fronts of the elbows are the most commonly affected locations.

In adults, the hands and feet are frequently the primary sites of atopic dermatitis.

It’s important to note that scratching exacerbates the symptoms of atopic dermatitis, intensifying the itch and further damaging the skin. Individuals with this condition also have a heightened susceptibility to developing skin infections in the affected areas.

Furthermore, many people who experience atopic dermatitis also go on to develop allergic rhinitis (hay fever) or asthma, indicating a potential link between these conditions.

Causes and Predisposing Factors of Atopic Dermatitis

The precise cause of atopic dermatitis (AD) remains elusive, but current understanding points to a complex interplay of genetic, immunological, environmental, and skin barrier-related factors.

Genetic Predisposition: Genetics play a substantial role in AD susceptibility.

Twin Studies: Research involving identical twins highlights a strong genetic component. If one identical twin has atopic dermatitis, there is a high probability (approximately 85%) that the other twin will also develop the condition.

Family History of Atopy: A significant proportion of individuals with AD have a family history of atopic conditions. Atopy refers to a predisposition to immediate-onset allergic reactions (Type 1 hypersensitivity reactions). These reactions can manifest as various allergic diseases, including asthma, food allergies, atopic dermatitis, and allergic rhinitis (hay fever).

Immune System Dysregulation: An overactive or dysfunctional immune system is a key feature in AD.

Immune Hyperreactivity: Individuals with AD exhibit an immune system that is overly sensitive and reactive to common substances in the environment that are normally harmless.

Inflammatory Cascade: This immune system hyperreactivity triggers the release of inflammatory chemicals within the skin. These inflammatory mediators are responsible for the characteristic signs and symptoms of AD, such as redness, intense itching, and inflammation.

Environmental Exposures: Exposure to various environmental factors can act as triggers, initiating or worsening AD symptoms in susceptible individuals. These factors include:

Indoor Allergens: Dust mites, pet dander (animal skin flakes and proteins), pollen (seasonal and perennial).

Irritants: Smoke (tobacco smoke, air pollution), certain chemicals (fragrances, dyes, preservatives in skincare products), dry air (low humidity environments), and emotional stress.

Frequent Hand Washing/Irritant Exposure: Repeated exposure to certain chemicals or frequent handwashing, especially with harsh soaps, can exacerbate AD symptoms by disrupting the skin barrier.

Urban and Dry Climates: Individuals residing in urban areas and dry climates tend to have a higher prevalence of atopic dermatitis, possibly due to increased exposure to pollutants and drier air, which can compromise skin barrier function.

Skin Barrier Defects: A compromised skin barrier is a critical factor in the development of AD.

Impaired Permeability: Individuals with AD have structural and functional abnormalities in their skin barrier, the outermost layer of skin. This defective barrier becomes more permeable, meaning it allows allergens, irritants, and microorganisms to penetrate the skin more easily.

Increased Allergen Penetration: The compromised skin barrier facilitates the entry of environmental allergens and irritants into the deeper layers of the skin.

Inflammation and Symptom Development: This increased penetration triggers an inflammatory response within the skin, leading to the characteristic inflammation, dryness, and itch of atopic dermatitis.

Staphylococcus aureus Exploitation: Research indicates that abnormalities in the skin barrier in AD are exploited by Staphylococcus aureus bacteria. S. aureus colonization on compromised skin can further trigger the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines (immune signaling molecules), thereby exacerbating the AD condition.

Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) Colonization: S. aureus is a common bacterium found on human skin.

Skin Colonization in AD: In individuals with atopic dermatitis, S. aureus bacteria can readily colonize the skin, particularly in areas affected by eczema.

Toxin Production and Inflammation: S. aureus produces toxins and other substances that can act as irritants and further amplify skin inflammation in AD. This bacterial colonization contributes to the severity and persistence of AD symptoms.

Calcium Carbonate in Household Water: Water hardness may play a role in AD development, particularly in children.

Hard Water Link: Studies have suggested a potential association between childhood atopic dermatitis and the level of calcium carbonate in household water (“hard water”).

Increased Risk: Children residing in areas with high levels of calcium carbonate in their tap water may have a higher likelihood of developing atopic dermatitis compared to those in areas with softer water.

Hygiene Hypothesis: This hypothesis proposes that early childhood exposure to microbes and certain allergens may play a role in immune system development and allergy risk.

Early Allergen Exposure: The hygiene hypothesis suggests that when children are raised in environments with greater exposure to diverse microbes and common allergens early in life, their immune systems may be more likely to develop tolerance to these substances.

Modern Sanitary Environments: Conversely, children raised in modern, highly sanitized environments with reduced microbial exposure may be less likely to develop immune tolerance early in life.

Later Allergy Development: According to this hypothesis, when children with less early exposure are subsequently exposed to common allergens, their immune systems may be more prone to overreact, leading to the development of allergic conditions like atopic dermatitis.

Support for AD Link: Some research provides support for the hygiene hypothesis in relation to atopic dermatitis, suggesting that early environmental exposures may influence AD risk.

Common Triggers of Atopic Dermatitis Symptoms:

Various factors can trigger flare-ups or worsen existing symptoms of atopic dermatitis. Common triggers include:

Food Allergies: Certain food allergens can trigger eczema flare-ups in some individuals with AD. Common culprits include milk, eggs, peanuts, tree nuts, soy, and wheat. Identifying and managing food allergies, when relevant, can be an important part of AD management.

Stress: Emotional stress is a well-known trigger for many skin conditions, including atopic dermatitis. Periods of increased stress can exacerbate AD symptoms and lead to flare-ups.

Temperature and Humidity Extremes:

Heat and Humidity: Hot, humid weather can worsen AD in some individuals, leading to increased sweating and irritation.

Cold and Dry Air: Cold, dry air, particularly during winter months, can dry out the skin and trigger eczema flare-ups.

Certain Fabrics: Specific fabric types can irritate sensitive skin and trigger AD symptoms.

Wool: Wool fabrics are known to be itchy and irritating for many people with eczema.

Synthetic Fibers: Some synthetic fabrics may also be less breathable and cause skin irritation.

Harsh Soaps and Detergents: Many conventional soaps and laundry detergents contain harsh chemicals and fragrances that can strip the skin of its natural oils and irritate sensitive skin, triggering AD flare-ups.

Perfumes and Fragrances: Perfumes and fragrances, commonly found in skincare products, cosmetics, and household cleaners, are frequent irritants for individuals with atopic dermatitis and can worsen their symptoms. Fragrance-free products are generally recommended for those with AD.

Pathophysiology of Atopic Dermatitis

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is not an infectious condition. The underlying disease process is complex and is thought to involve a combination of hypersensitivity reactions resembling both Type I (immediate) and Type IV (delayed-type) allergy.

The development of AD can be summarized as a sequence of events:

Genetic Predisposition & Predisposing Factors: Individuals inherit a genetic susceptibility or acquire predisposing factors that set the stage for AD.

Skin Barrier Dysfunction: This predisposition or other factors ultimately lead to skin barrier dysfunction. This means the skin’s protective outer layer becomes compromised and weakened.

Increased Irritant Penetration: The defective skin barrier becomes more permeable. This allows environmental irritants, allergens, and microbes to penetrate the skin more easily than in healthy skin.

Exaggerated Immune Response: The immune system, particularly T-cells within the skin, becomes overactive and responds excessively to these newly penetrating triggers.

Release of Inflammatory Mediators: This exaggerated immune response triggers the release of various inflammatory chemicals, notably including histamines.

Skin Inflammation: The release of these inflammatory chemicals causes inflammation within the skin layers. This inflammation manifests as the classic signs of eczema:

Redness (erythema)

Swelling (edema)

Itching (pruritus)

Itch-Scratch Cycle: The intense itching sensation is a hallmark of AD. However, scratching the itchy skin, while providing temporary relief, actually worsens the inflammation. This initiates a vicious itch-scratch cycle, where scratching leads to more inflammation, which in turn increases itching, and so on.

Skin Microbiome Imbalance: The cycle of itching and scratching disrupts the skin’s natural balance of microorganisms (its normal flora). This can lead to an imbalance in the skin microbiome, particularly with an overgrowth of Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) bacteria.

S. aureus Exacerbation: The overcolonization of S. aureus further contributes to inflammation, as this bacteria can release toxins that worsen the eczematous skin condition.

Skin Thinning and Increased Vulnerability: Chronic inflammation combined with persistent scratching can lead to structural changes in the skin. Over time, the skin layers can become thinner. This thinning makes the skin more fragile and more susceptible to infections from bacteria, viruses, and fungi, as well as increased vulnerability to environmental damage from irritants and allergens.

Cytokine Release and Amplified Inflammation: Immune cells within the inflamed skin release signaling molecules called cytokines, especially interleukins. These cytokines, in turn, amplify the inflammatory response, creating a positive feedback loop that drives even more inflammation.

Eczematous Lesion Formation: The combined effects of:

Inflammation

Scratching

Dysregulated immune responses

Ultimately result in the development of the characteristic eczematous lesions of atopic dermatitis. These lesions are typically:

Red

Dry

Scaly patches of skin

Flare-up Triggers: Finally, various triggers, such as:

Allergens

Stress

Environmental factors

Can exacerbate the underlying inflammatory process and lead to periodic flare-ups of atopic dermatitis symptoms, characterized by periods of increased lesion severity, itching, and discomfort.

Signs and Symptoms of Atopic Dermatitis

Atopic dermatitis (AD) presents with a range of characteristic signs and symptoms affecting the skin. These can vary in severity and location, but commonly include:

Generalized Dry and Scaly Skin: The skin becomes noticeably dry and scaly across much of the body surface. Notably, the diaper area may be spared from this widespread dryness. This pervasive dryness is a primary feature of AD.

Intensely Itchy Lesions: A hallmark of AD are lesions that are intensely itchy and appear as:

Red: Inflamed and erythematous.

Splotchy: Unevenly distributed patches.

Raised: Elevated above the surrounding skin.

Located in Flexural Areas: Predominantly found in skin creases and folds, such as:

Bends of the arms (elbow flexures).

Backs of the knees (knee flexures).

Face, particularly in infants and young children.

Neck folds.

Subtle Eyelid Signs: Specific, less obvious signs can appear around the eyes:

Dennie-Morgan Infraorbital Fold: A distinctive crease or line that develops beneath the lower eyelid.

Infra-auricular Fissure: A groove or crack-like line located in the skin immediately in front of the ear.

Periorbital Pigmentation: Darkening of the skin specifically around the eyelids, creating a shadowed appearance.

Post-Inflammatory Hyperpigmentation (“Dirty Neck”): After inflammation subsides, a darkening of the skin (hyperpigmentation) may occur on the neck. This can give the neck a characteristic appearance sometimes described as “dirty neck.”

Skin Changes Indicating Complications: On the trunk (torso), various skin changes can develop, including:

Lichenification: Thickening and a leathery texture of the skin, resulting from chronic scratching and rubbing.

Excoriation: Abrasions or scratch marks on the skin surface due to intense scratching.

Erosion: Loss or wearing away of the superficial layers of the skin, often appearing as raw or open areas.

Crusting: Formation of a hardened layer or scab on the skin surface, composed of dried fluid or exudate. The presence of erosion or crusting can be indicative of a secondary bacterial infection.

Flexural Rash Distribution with Variable Features: Rashes in AD often exhibit a “flexural distribution,” meaning they favor skin folds and creases. These rashes may present with:

Ill-defined Edges: The borders of the rash are not sharply demarcated, blending somewhat into the surrounding skin.

Hyperlinearity (sometimes): An increase in the prominence and visibility of the natural skin lines, particularly noticeable on the wrists, finger knuckles, ankles, feet, and hands.

Additional Common Symptoms:

Dry, Itchy Skin: The skin feels persistently dry and is characterized by intense itching, which is often the most bothersome symptom.

Redness and Inflammation: Affected skin areas appear visibly red and inflamed. Small bumps or tiny blisters (vesicles) may also be present.

Eczema Patches: Dry, scaly patches develop. These patches may become thickened, crusted, or begin to ooze fluid.

Oozing and Crusting: Blisters or lesions can rupture, releasing fluid that dries and forms a crust on the skin surface.

Lichenification (Thickened Skin): With persistent scratching over time, the skin may become thickened, hardened, and develop exaggerated skin markings (lichenification).

- Skin infections: Due to compromised skin barrier, infections such as staph or yeast can occur.

Allergic reactions: Atopic dermatitis can be triggered by allergens, leading to flare-ups with symptoms such as hives,

swelling, and itching.

Diagnosis of Atopic Dermatitis

Atopic dermatitis (AD) diagnosis is primarily clinical. This means it is typically based on recognizing the characteristic signs and symptoms during a physical examination, rather than relying on specific laboratory tests. While no single test confirms AD, established diagnostic criteria are often used to aid in the process, especially in research settings.

Clinical Assessment:

Diagnosis begins with a thorough clinical assessment, involving:

Physical Examination: The doctor will carefully examine the skin, looking for visual signs of atopic dermatitis. Key signs include:

Dry, itchy skin – noting the texture and dryness of the skin.

Redness and swelling – observing areas of inflammation and erythema.

Scaling and crusting – identifying any patches of scaly or crusted skin.

Lichenification – assessing for thickened, leathery skin due to chronic scratching.

Medical History Review: The doctor will take a detailed patient history, including:

Family history: Inquiring about a family history of atopic dermatitis or other atopic conditions (asthma, allergic rhinitis).

Symptom history: Gathering information about the onset, duration, and characteristics of the skin symptoms.

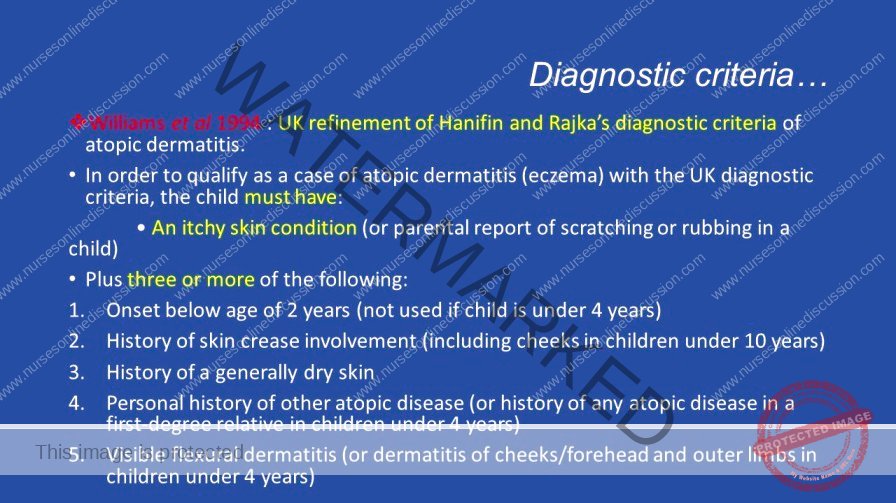

To aid in diagnosis and ensure consistency, standardized diagnostic criteria, such as the UK Diagnostic Criteria, are often utilized.

UK Diagnostic Criteria for Atopic Dermatitis

The UK Diagnostic Criteria for atopic dermatitis require the presence of itchy skin (or evidence of scratching/rubbing), plus three or more of the following features:

Involvement of Skin Creases: Eczema affecting skin folds.

Flexural Dermatitis: Presence of eczema in typical flexural areas:

Fronts of ankles

Antecubital fossae (elbow creases)

Popliteal fossae (behind knees)

Skin around the eyes

Neck

In young children (<10 years old): Cheeks may be included.

Personal or Family History of Atopy:

Personal History: Patient has a history of asthma or allergic rhinitis.

Family History (for children ≤4 years old): Family history of asthma or allergic rhinitis if the patient is a young child.

Early Onset of Symptoms:

Symptom Onset Before Age 2: Symptoms began before the age of 2 years. (Note: This criterion is primarily applied to patients ≥4 years old when assessing their history).

History of Dry Skin:

Dry Skin in the Past Year: Patient reports a history of generalized dry skin within the past year.

Visible Dermatitis in Characteristic Locations: Eczema is observed in typical locations:

Flexural Surfaces (patients ≥age 4): Visible eczema in skin creases.

Cheeks, Forehead, and Extensor Surfaces (patients <age 4): In younger children, eczema may be more prominent on the cheeks, forehead, and outer (extensor) surfaces of limbs.

Explanation of the UK Diagnostic Criteria

Itchy skin or evidence of rubbing or scratching: This criterion highlights the central role of itch in AD.

Skin creases are involved: This points to the characteristic distribution of eczema in body folds.

Flexural dermatitis: Emphasizes the typical location of AD rashes in flexural areas.

History of asthma or allergic rhinitis: Recognizes the strong association of AD with other atopic conditions.

Symptoms began before age 2: Reflects the common childhood onset of AD.

History of dry skin: Acknowledges dryness as a fundamental feature of AD-affected skin.

Dermatitis is visible on flexural surfaces or on the cheeks, forehead, and extensor surfaces: Highlights the age-related variations in rash distribution patterns.

Additional Investigations

While not routinely required for diagnosis, in certain situations, a doctor might order further investigations to support the clinical diagnosis or rule out other conditions:

Allergy Testing: May be used to identify specific allergens that could be triggering or exacerbating the atopic dermatitis.

Skin Prick Tests: Involve applying small amounts of suspected allergens to the skin and observing for localized allergic reactions.

Blood Tests: Measure levels of allergen-specific IgE antibodies in the blood, indicating potential allergic sensitization.

Patch Testing: A type of allergy test primarily used to diagnose contact dermatitis.

Involves applying small patches containing potential contact allergens to the skin for a period (usually 48 hours).

The skin is then examined for signs of a delayed allergic reaction at the patch sites, helping to identify substances causing contact allergies.

Differential Diagnosis

It’s important to differentiate atopic dermatitis from other skin conditions that can present with similar symptoms. Conditions to consider in the differential diagnosis include:

Contact Dermatitis: Inflammation of the skin caused by direct contact with irritants or allergens.

Seborrheic Dermatitis: A common skin condition causing scaly, greasy patches, primarily on the scalp and face.

Psoriasis: A chronic autoimmune skin disease characterized by raised, red, scaly plaques, often with a silvery appearance.

Other Forms of Eczema: Various other types of eczema exist, such as nummular eczema or dyshidrotic eczema, which may need to be distinguished from atopic dermatitis.

Treatment of Atopic Dermatitis

While there is currently no cure for atopic dermatitis (AD), effective treatments are available to significantly reduce the severity and frequency of flare-ups. Management strategies involve both preventive measures and therapeutic medications.

Preventive Measures

Preventive strategies are crucial for long-term management and aim to minimize triggers and maintain skin health.

Trigger Avoidance: Identifying and diligently avoiding specific triggers that worsen AD symptoms is a cornerstone of management. Common triggers include:

Wool clothing and synthetic fabrics

Harsh soaps and detergents

Perfumes and fragranced products

Chlorine (in swimming pools or cleaning products)

Dust mites

Cigarette smoke

Daily Bathing and Moisturizing Routine: Establishing a consistent daily skincare regimen is essential:

Daily Lukewarm Baths: Bathe daily using lukewarm water, avoiding hot water which can dry out the skin.

Fragrance-Free Moisturizer Application: Immediately after bathing, while skin is still damp, generously apply a fragrance-free, hypoallergenic moisturizer over the entire body. This helps to lock in moisture and maintain skin hydration, reducing the need for more potent medications.

Gentle Cleansing Agents: Using mild soaps and detergents is crucial to minimize skin irritation:

Mild, Fragrance-Free Products: Opt for gentle, fragrance-free soaps, body washes, and laundry detergents specifically formulated for sensitive skin. Harsh chemicals and fragrances can strip the skin of natural oils and exacerbate AD.

Appropriate Clothing Choices: Clothing can significantly impact AD symptoms.

Loose-fitting Cotton Clothing: Wear loose-fitting clothing made from breathable cotton. Cotton allows the skin to breathe, minimizing friction and irritation. Avoid tight-fitting synthetic fabrics or wool, which can trap heat and irritate sensitive skin.

Stress Management: Stress is a known trigger for AD flare-ups.

Healthy Stress Reduction Techniques: Incorporate healthy stress management techniques into daily life. Effective methods include:

Regular exercise

Listening to calming music

Practicing meditation or mindfulness

Engaging in hobbies and relaxing activities.

Managing stress can help reduce the frequency and severity of AD flares.

Medications

Medications play a key role in managing active AD flare-ups and controlling inflammation and itching.

Topical Corticosteroids: These are a mainstay treatment for reducing inflammation and itch in AD.

Effective Anti-Inflammatories: Topical corticosteroids like hydrocortisone are effective at reducing skin inflammation and alleviating itching.

Application Frequency: They are typically applied directly to the affected skin areas once or twice daily, as directed by a healthcare provider.

Topical Calcineurin Inhibitors (TCIs): These non-steroidal medications offer an alternative to corticosteroids.

Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory: TCIs, such as tacrolimus and pimecrolimus, are non-steroidal alternatives that effectively reduce inflammation in AD.

Short-Term Use: They are typically used for shorter durations or for maintenance therapy, as long-term use can carry potential side effects like skin irritation and a burning sensation upon application.

Systemic Immunosuppressants: For severe, recalcitrant AD that does not respond to topical treatments, systemic medications may be necessary.

Immune System Suppression: Systemic immunosuppressants, including cyclosporine, methotrexate, and azathioprine, work by suppressing the overactive immune system, thereby reducing overall inflammation.

Severe Cases: These medications are generally reserved for severe AD cases that have not responded adequately to topical therapies due to their potential for more significant side effects and the need for careful monitoring.

Antidepressants and Naltrexone: These medications can be used to address a prominent symptom of AD – itching.

Pruritus Control: Antidepressants and naltrexone, an opioid antagonist, can be prescribed to help manage and control persistent and severe pruritus (itching) associated with AD, improving patient comfort and sleep quality.

Antibiotics: Bacterial infections are a common complication of AD due to skin barrier compromise.

Treating Secondary Bacterial Infections: Antibiotics, either topical or oral, may be prescribed to treat secondary bacterial skin infections that can develop in areas affected by AD, especially if signs of infection (increased redness, pus, crusting) are present.

Phototherapy: Light therapy can be a beneficial treatment option for some individuals with AD.

Ultraviolet (UV) Light Exposure: Phototherapy involves controlled exposure of the skin to specific wavelengths of ultraviolet (UV) light, typically UVB or UVA.

Inflammation Reduction and Skin Improvement: UV light therapy can help reduce skin inflammation, alleviate itching, and improve the overall appearance and condition of AD-affected skin.

Other Supportive Treatments

In addition to standard medications, several other treatments can complement AD management:

Moisturizers (Emollients): Consistent and liberal use of moisturizers is fundamental to AD care.

Hydration and Barrier Repair: Regularly applying emollients helps to hydrate the skin, restore the skin barrier function, and reduce dryness and itching. Moisturizers are used frequently, even when AD is well-controlled, as a preventative measure.

Salt Water Baths: Therapeutic baths can provide soothing relief for AD symptoms.

Soothing and Anti-inflammatory: Soaking in salt water baths (using bath salts or Epsom salts) can help soothe irritated skin, reduce inflammation, and cleanse the skin gently.

Dilute Bleach Baths: Under medical supervision, dilute bleach baths can be beneficial.

Managing Bacterial Overgrowth: Dilute bleach baths, when used correctly and as directed by a physician, can help reduce Staphylococcus aureus bacteria on the skin, which can worsen AD symptoms. The concentration and frequency of bleach baths must be carefully followed to avoid skin irritation.

Vitamin D Supplementation: Some research suggests a potential link between vitamin D and AD.

Potential Symptom Improvement: There is limited evidence suggesting that vitamin D supplementation may help improve AD symptoms in some individuals, particularly those with vitamin D deficiency. However, more research is needed, and vitamin D is not considered a primary treatment.

Dietary Changes (Limited Role): Dietary changes are generally not a primary treatment for AD, unless specific food allergies have been identified through allergy testing.

Allergen Avoidance (If Identified): If specific food allergens have been confirmed to trigger AD flare-ups, avoiding these identified foods can be beneficial in managing symptoms in those individuals. However, routine elimination diets without identified food allergies are not generally recommended for AD.

Complications of Atopic Dermatitis

Atopic dermatitis (AD), while primarily a skin condition, can lead to various complications affecting different aspects of health and well-being.

Skin Infections: Individuals with AD have a higher susceptibility to developing infections of the skin due to the compromised skin barrier. These infections can be:

Eczema Herpeticum (Viral): A severe skin infection caused by the herpes simplex virus.

Impetigo (Bacterial): A bacterial skin infection, often caused by Staphylococcus aureus or Streptococcus pyogenes.

Allergic Contact Dermatitis: Having AD increases the likelihood of developing allergic contact dermatitis. This is a distinct type of skin reaction triggered when the skin comes into direct contact with an allergen, causing localized inflammation and rash at the contact site.

Hand Eczema: Atopic dermatitis can specifically manifest as hand eczema, affecting the skin of the hands. This form of eczema can be particularly challenging to manage due to frequent hand use and exposure to irritants, and it can significantly hinder daily activities requiring hand dexterity.

Sleep Disturbances: The intense itching associated with AD can severely disrupt sleep patterns. The discomfort and urge to scratch often make it difficult to fall asleep and stay asleep, leading to fatigue and daytime impairment.

Psychological Impact: Living with AD can take a toll on mental health. The visible skin symptoms, chronic itch, and impact on daily life can contribute to:

Anxiety

Depression

Reduced self-esteem

Increased Risk of Atopic March Conditions: Individuals with AD are at a higher risk of developing other conditions within the “atopic march,” a progression of allergic diseases. These include:

Asthma

Hay fever (Allergic Rhinitis)

Reduced Quality of Life: Atopic dermatitis can significantly diminish overall quality of life. The persistent symptoms and associated complications can impact various aspects of daily living, including:

Work performance

Academic performance at school

Participation in social activities

Erythroderma: A rare but serious complication of AD. Erythroderma involves widespread inflammation affecting a large percentage of the body surface, leading to skin that becomes extensively red, swollen, and intensely itchy. This condition requires prompt medical attention and can be life-threatening if left untreated.

Lymphoma Risk: While less common, individuals with severe and persistent atopic dermatitis have been observed to have a slightly increased risk of developing lymphoma. Lymphoma is a type of cancer that originates in the lymphatic system. The reasons for this association are still being researched.

We are a supportive platform dedicated to empowering student nurses and midwives through quality educational resources, career guidance, and a vibrant community. Join us to connect, learn, and grow in your healthcare journey

Quick Links

Our Courses

Legal / Policies

Get in Touch

(+256) 790 036 252

(+256) 748 324 644

Info@nursesonlinediscussion.com

Kampala ,Uganda

© 2025 Nurses online discussion. All Rights Reserved | Design & Developed by Opensigma