Medical Conditions Affecting the Nervous System

Subtopic:

Seizures Disorders

A seizure arises from a temporary burst of irregular electrical activity within the brain or central nervous system. This disruption leads to unusual experiences that can affect:

Motor Function: Abnormal movements.

Sensory Perception: Unusual sensations.

Psychomotor Activity: Changes in mental and physical activity.

More technically, a seizure is an uncontrolled electrical discharge starting in the brain’s cortex (outer layer). This discharge interferes with normal brain operation.

Epilepsy: When seizures become a recurring pattern – intermittent and happening again and again – it’s termed epilepsy. Epilepsy is defined by this tendency to have repeated seizures.

Manifestations of a Seizure: A seizure can cause various changes, including:

Altered Consciousness: Changes in awareness or alertness.

Abnormal Sensations: Unusual feelings or perceptions.

Focal Involuntary Movements: Localized muscle spasms or twitching.

Convulsions: Full-body, uncontrolled muscle contractions (violent involuntary contraction of voluntary muscles).

Prevalence: Approximately 2% of adults will have a seizure at some point in their lives. However, for around two-thirds of these individuals, it will be an isolated event and not recur.

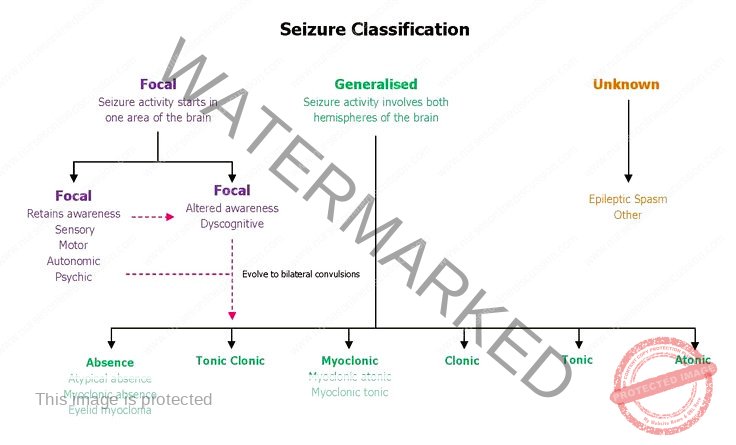

Classification of Seizure Disorders:

Seizure disorders are broadly categorized into two main types:

Epileptic Seizures (Epilepsy):

Epilepsy Defined: Epilepsy is a chronic neurological condition where brain activity becomes disordered, leading to recurrent seizures and potential alterations in behavior, sensations, and awareness.

Key Feature: Recurrent, Unprovoked Seizures: Epilepsy, also known as epileptic seizure disorder, is a long-term brain condition marked by seizures that:

Are recurrent: They happen more than once.

Are unprovoked: They aren’t triggered by a temporary, reversible cause (stressor).

Occur more than 24 hours apart: To distinguish them from seizure clusters or status epilepticus.

Not Just a Single Seizure: A single, isolated seizure is not classified as epilepsy.

Idiopathic vs. Symptomatic Epilepsy:

Idiopathic Epilepsy: Often, the cause of epilepsy is unknown (idiopathic).

Symptomatic Epilepsy: In other cases, epilepsy is caused by underlying brain disorders, such as:

Brain malformations.

Strokes.

Brain tumors.

Symptomatic Epileptic Seizures: Seizures that arise from a known cause (like a brain tumor or stroke) are called symptomatic epileptic seizures.

Age Groups Affected by Symptomatic Epilepsy: Symptomatic seizures are particularly common in:

Newborns (neonates)

The elderly.

Cryptogenic Epilepsy: This is epilepsy that is believed to have a specific cause, but that cause cannot currently be identified using available diagnostic methods.

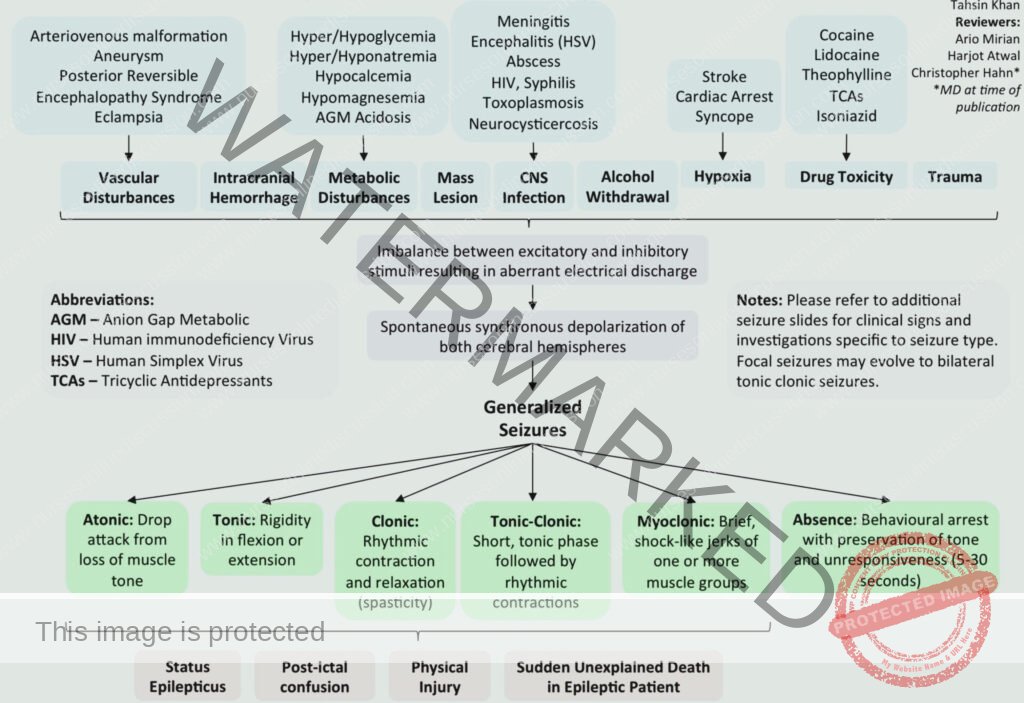

Non-Epileptic Seizures:

Provoked Seizures: Non-epileptic seizures are triggered or provoked by a temporary issue or stressor. These are reactions to something transient, not epilepsy itself.

Examples of Provoking Factors:

Metabolic disorders.

Central nervous system (CNS) infections.

Cardiovascular disorders.

Drug toxicity or drug withdrawal.

Psychogenic disorders.

Febrile Seizures: In children, a common trigger is fever, which can cause febrile seizures.

Psychogenic Nonepileptic Seizures (PNES) / Pseudoseizures: These are episodes that look like seizures but are caused by psychological factors, not abnormal brain electrical activity. They occur in individuals with psychiatric disorders and are not true epileptic events.

Etiology of Seizure Disorders

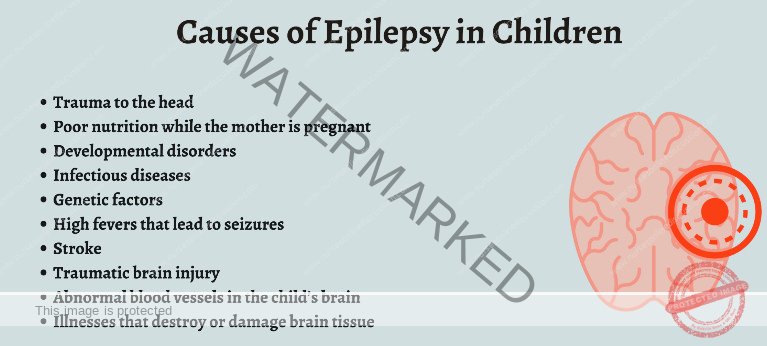

Seizure disorders can arise from a wide range of causes, often varying with age.

I. Age-Specific Causes:

A. Before Age 2:

Fever: Febrile seizures, triggered by fever, are a common cause in this young age group.

Birth or Developmental Defects: Congenital structural brain abnormalities or developmental issues present from birth.

Birth Injuries: Trauma sustained during childbirth.

Metabolic Disorders: Inborn errors of metabolism that disrupt normal biochemical processes.

B. Ages 2 to 14:

Idiopathic Seizure Disorders: In many children in this age range, the cause of seizures remains unknown (idiopathic), categorized as idiopathic seizure disorders of childhood.

C. Adults:

Cerebral Trauma: Traumatic brain injury (TBI) from accidents or injuries.

Alcohol Withdrawal: Seizures as a consequence of abrupt alcohol cessation in individuals with alcohol dependence.

Brain Tumors: Tumors within the brain tissue.

Strokes: Cerebrovascular events causing brain tissue damage.

Unknown Cause (50%): In a significant proportion of adult-onset seizures, the underlying etiology is not identified (idiopathic).

D. The Elderly:

Brain Tumors: Brain tumors are a relatively more frequent cause of new-onset seizures in older adults compared to younger adults.

Strokes: Cerebrovascular disease leading to stroke is a major cause of seizures in the elderly.

E. Reflex Epilepsy:

External Stimuli Triggers: In rare cases of reflex epilepsy, seizures are predictably and reliably provoked by specific external stimuli, such as flashing lights, certain sounds, or tactile stimuli.

F. Cryptogenic and Refractory Epilepsy:

Anti-NMDA Receptor Encephalitis: A rare autoimmune condition, particularly affecting young women, characterized by psychiatric symptoms, seizures, and movement disorders. Often associated with ovarian teratomas.

II. General Causes of Seizures (Across All Ages):

These causes can induce seizures across different age groups:

Autoimmune Disorders:

Cerebral Vasculitis: Inflammation of blood vessels in the brain.

Anti-NMDA Receptor Encephalitis: (As mentioned above, can be a cause of cryptogenic epilepsy).

Multiple Sclerosis (MS): While less common, MS can sometimes lead to seizures due to brain lesions.

Cerebral Edema: Brain swelling, regardless of cause.

Pregnancy-Related Conditions:

Eclampsia: Seizures related to severe hypertension in pregnancy.

Hypertensive Encephalopathy: Brain dysfunction due to severely elevated blood pressure.

Cerebral Ischemia or Hypoxia: Conditions leading to reduced blood flow or oxygen supply to the brain:

Cardiac Issues: Cardiac arrhythmias, heart failure, cardiac arrest.

Carbon Monoxide Toxicity: CO poisoning.

Hypoxic Events: Drowning, suffocation, severe respiratory failure.

Stroke: Ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke.

Head Trauma: Brain injuries from various causes, including both birth-related trauma and acquired traumatic brain injuries at any age.

Central Nervous System (CNS) Infections:

AIDS (Advanced HIV infection)

Brain Abscess

Malaria (Cerebral Malaria)

Meningitis (Bacterial, Viral, Fungal)

Neurocysticercosis (Parasitic infection)

Neurosyphilis (Syphilis affecting the brain)

Rabies

Tetanus

Toxoplasmosis (especially in immunocompromised)

Viral Encephalitis (various viral causes)

Congenital or Developmental Abnormalities:

Brain malformations present at birth.

Developmental disorders affecting brain structure or function.

Drugs and Toxins: A wide range of substances can induce seizures:

Prescription Drugs: Some medications, especially in overdose or withdrawal.

Illicit Drugs: Cocaine, amphetamines, etc.

Environmental Toxins: Camphor, ciprofloxacin (in rare cases), and many others.

Expanding Intracranial Lesions: Space-occupying lesions within the skull:

Intracranial Hemorrhage (Bleeding)

Hydrocephalus (Increased CSF)

Brain Tumors

Hyperpyrexia: Extremely high body temperature:

Drug-induced hyperthermia.

Heatstroke.

Metabolic Disturbances: Electrolyte and metabolic imbalances:

Hypocalcemia: Low blood calcium (often linked to hypoparathyroidism).

Hypoglycemia: Low blood glucose.

Hyponatremia: Low blood sodium.

Less Common Metabolic Causes: Aminoacidurias, hepatic encephalopathy (liver failure), uremic encephalopathy (kidney failure), hyperglycemia (high blood glucose – nonketotic hyperosmolar state), hypomagnesemia (low magnesium), hypernatremia (high sodium).

Neonatal Specific Metabolic Cause:

Vitamin B6 (Pyridoxine) Deficiency: A rare but treatable cause of neonatal seizures.

Withdrawal Syndromes: Abrupt cessation of certain substances:

Alcohol withdrawal.

Withdrawal from anesthetics.

Barbiturate withdrawal.

Benzodiazepine withdrawal.

Classification of Partial Seizures

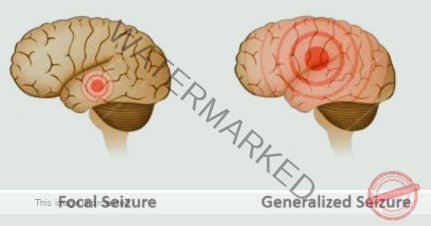

In partial seizures, the abnormal electrical discharge originates in a specific area within one cerebral hemisphere (cortex). These seizures are often linked to underlying structural abnormalities within that brain region.

Partial seizures are broadly classified into:

Simple Partial Seizures (Focal Seizures without Impairment of Consciousness): These seizures are characterized by localized symptoms, but consciousness and awareness remain intact.

Complex Partial Seizures (Focal Seizures with Impairment of Consciousness): These seizures also start focally, but consciousness or awareness is affected or lost during the event.

It’s important to note that partial seizures can sometimes progress to involve the entire brain in what’s called secondary generalization. In this scenario, a partial seizure spreads and triggers a generalized seizure, resulting in a loss of consciousness. This spread of electrical activity across both cerebral hemispheres can happen so quickly that the initial partial seizure phase might be subtle or very brief, making it difficult to recognize clinically.

Symptoms and Signs of Partial Seizures

The specific signs and symptoms observed during a partial seizure depend on the particular area of the brain that is affected by the abnormal electrical discharge.

A. Simple Partial Seizures (Focal Seizures without Impairment of Consciousness):

Aura as Onset: Simple partial seizures may often begin with an aura. An aura is essentially the beginning of a simple partial seizure experienced as a warning sign. Auras are focal seizures themselves and can manifest as:

Motor Activity: Involuntary movements or muscle twitching localized to a body part.

Sensory Sensations: Unusual feelings such as tingling, numbness (paresthesias), or altered sensations.

Autonomic Changes: Physiological changes such as a rising sensation in the stomach area (epigastric sensation), sweating, or changes in heart rate.

Psychic Experiences: Emotional or cognitive changes like unusual smells, a sense of fear or anxiety that arises suddenly, or the feeling of déjà vu (a sense of familiarity with a new situation).

Spontaneous Termination: Most simple partial seizures are brief, typically resolving on their own within 1 to 2 minutes.

Postictal State (Typically Absent): Unlike generalized seizures, simple partial seizures do not usually result in a significant postictal state.

Interictal Neurological Normality: Between seizures, individuals with simple partial seizures generally appear neurologically normal. However, it’s important to consider that medications used to control seizures, especially at higher doses (anticonvulsants), can sometimes affect alertness and cognitive function in general.

B. Jacksonian Seizures (A Type of Simple Partial Motor Seizure):

Characteristic Motor March: Jacksonian seizures are a specific type of simple partial motor seizure. They are defined by focal motor symptoms that begin in a localized area and then progressively spread or “march” through the body.

Classic Progression: Often, the seizure activity starts in one hand, and then the motor symptoms sequentially move up the arm (Jacksonian march).

Facial Onset: In other cases, Jacksonian seizures may begin in the face, then spread to involve the arm, and potentially even the leg on the same side of the body.

Fencing Posture: Some motor onset partial seizures may start with involuntary raising of an arm, accompanied by the head turning towards the raised arm, sometimes described as a “fencing posture”.

C. Complex Partial Seizures (Focal Seizures with Impairment of Consciousness):

Aura Precedence: Complex partial seizures are frequently preceded by an aura, similar to simple partial seizures, acting as a warning sign.

Impaired Consciousness: A key feature is that consciousness is impaired during the seizure. While individuals might not be fully unconscious, their awareness of themselves and their surroundings is significantly reduced. They may appear to be staring blankly into space. However, some level of environmental awareness may persist (e.g., reacting to or withdrawing from a painful stimulus).

Automatisms: During complex partial seizures, individuals often exhibit automatisms, which are repetitive, semi-purposeful, involuntary movements. These can include:

Oral Automatisms: Repetitive mouth movements like involuntary chewing motions or lip smacking.

Limb Automatisms: Automatic, seemingly purposeless movements of the limbs, especially the hands (e.g., fumbling, picking at clothes).

Vocalization (Non-Meaningful): Individuals may utter unintelligible sounds or words without comprehension of what they are saying.

Resistance to Assistance: They may exhibit resistance to assistance or restraint during the seizure as they are confused and disoriented.

Posturing: Tonic or dystonic posturing can occur in an extremity, typically on the side of the body opposite to the seizure’s origin in the brain (contralateral).

Head and Eye Deviation: The head and eyes may involuntarily turn or deviate, usually in a direction away from the seizure’s origin in the brain (contralateral to the seizure focus).

Leg Movements: In seizures originating from specific brain regions (medial frontal or orbitofrontal areas), bicycling or pedaling movements of the legs may be observed.

Duration and Postictal Confusion:

Motor symptoms usually subside relatively quickly, within 1 to 2 minutes.

However, confusion and disorientation can linger for an additional 1 to 2 minutes or even longer after the motor symptoms cease.

Postictal Amnesia: Amnesia for the seizure event and the immediate postictal period is common.

Potential Agitation on Restraint: Patients may become agitated or lash out if they are physically restrained during the seizure or as they are regaining consciousness, particularly if the seizure progresses to a generalized tonic-clonic seizure. However, unprovoked, truly aggressive behavior is unusual in the postictal phase.

Memory Impairment (Temporal Lobe Focus):

Seizures originating in the left temporal lobe may be associated with verbal memory problems.

Seizures from the right temporal lobe may lead to difficulties with visual-spatial memory.

Generalized Seizures

Generalized seizures involve abnormal electrical activity across the entire brain cortex from the start. Consciousness is typically lost. Often linked to metabolic or genetic disorders.

Types of Generalized Seizures:

Infantile Spasms:

Sudden flexion and adduction of arms, trunk flexion.

Brief seizures (seconds), recur many times daily.

Occur in first 5 years, replaced by other seizure types later.

Developmental defects are common.

Typical Absence Seizures (Petit Mal):

Brief loss of consciousness (10-30 seconds).

Eyelid fluttering may occur.

Axial muscle tone loss may or may not happen.

No falling or convulsions; abrupt stop and resume activity without postictal effects or awareness of seizure.

Genetic, mainly in children.

Frequent seizures daily if untreated.

Often during quiet sitting, can be triggered by hyperventilation, rare during exercise.

Neurological and cognitive exams usually normal.

Atypical Absence Seizures:

Part of Lennox-Gastaut syndrome (severe epilepsy before age 4).

Longer duration than typical absence.

More pronounced jerking or automatic movements.

Less complete loss of awareness.

Often have nervous system damage, developmental delay, abnormal neurologic exam, other seizure types.

Continue into adulthood.

Atonic Seizures:

Mainly in children, often with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome.

Brief, complete loss of muscle tone and consciousness.

Sudden falls, risk of injury, especially head trauma.

Tonic Seizures:

Mostly during sleep, in children.

Commonly linked to Lennox-Gastaut syndrome.

Tonic (sustained) muscle contraction of axial muscles, spreading to limb muscles.

Short duration (10-15 seconds).

Longer seizures may have rapid clonic jerks at the end.

Tonic-Clonic Seizures (Grand Mal):

Can be primarily or secondarily generalized.

Primarily Generalized:

Sudden outcry at onset.

Loss of consciousness, falling.

Tonic contraction followed by clonic (alternating contraction/relaxation) movements in limbs, trunk, head.

Urinary/fecal incontinence, tongue biting, frothing at mouth may occur.

Lasts 1-2 minutes.

No aura.

Secondarily Generalized:

Start as simple or complex partial seizure, then generalize to tonic-clonic.

Myoclonic Seizures:

Brief, lightning-like jerks of limb(s) or trunk.

Can be repetitive, leading to tonic-clonic seizure.

Bilateral or unilateral jerks.

Consciousness is retained unless seizure evolves to tonic-clonic.

Juvenile Myoclonic Epilepsy:

Epilepsy syndrome with myoclonic, tonic-clonic, and absence seizures.

Onset in adolescence.

Starts with bilateral, synchronous myoclonic jerks, often followed by generalized tonic-clonic seizures (90% cases).

Often occur on awakening, especially after sleep deprivation or alcohol.

Absence seizures in about one-third of patients.

GENERAL MANAGEMENT OF SEIZURE DISORDERS

During a Seizure Attack (First Aid):

Ensure Safety:

Be aware of warning signs if present.

Gently lay the person down on a flat surface.

Check and ensure the immediate surroundings are safe.

Remove Hazards: Clear the area of any potentially dangerous objects (e.g., sharp items).

Do Not Restrain: Refrain from physically restraining the individual during the seizure.

Protect Airways: Do not put anything into the person’s mouth.

Note Duration: Time the seizure – note the start and end times for medical evaluation.

Post-Seizure Care:

Allow the person to rest and recover after the seizure.

Offer refreshments if they are fully conscious and able to take them.

Drug Management:

Anticonvulsant Medications (AEDs):

Utilize medications like diazepam, phenytoin, sodium valproate, and others as prescribed.

Strictly adhere to prescribed dosages and administration schedules.

Severe Epileptic Attack (Pediatric/Medical/Psychiatric Emergency):

Anticonvulsant Administration: Promptly administer appropriate anticonvulsant medication.

Cardio-Respiratory Support: Immediately provide support for cardiac and respiratory functions, including airway management and oxygenation.

Prevent Injury from Falls: Ensure a safe environment to prevent injuries during seizure activity.

Intravenous Fluid Administration: Administer IV fluids to maintain hydration.

Hypoglycemia Prevention: Monitor and maintain blood glucose levels to prevent hypoglycemia.

Long-Term Management (Epilepsy):

Individualized Treatment Plans: Develop a personalized treatment strategy with healthcare team.

Consistent Medication Adherence: Stress and ensure regular intake of prescribed anticonvulsant medications.

Lifestyle Adjustments: Promote a healthy lifestyle including regular sleep, stress management, and balanced nutrition.

Trigger Management: Identify and manage potential seizure triggers (e.g., stress, sleep deprivation).

Seizure Action Plan: Create a detailed seizure action plan collaboratively with healthcare providers for emergency situations.

Regular Medical Follow-Up: Schedule and attend routine medical appointments to monitor condition and adjust treatment.

Educational Resources: Provide educational resources and support for patients and families about epilepsy.

Psychosocial Support: Integrate psychosocial interventions to address emotional and mental health aspects of living with epilepsy.

Emergency Medication Access: Ensure readily available emergency medications for prolonged seizures (rescue medications).

Multidisciplinary Care: Involve a team including neurologists, psychologists, social workers for comprehensive care.

Nursing Interventions for Seizure Disorder

Prevent Trauma/Injury:

Educate caregivers on seizure recognition and management.

Recommend tympanic thermometers over breakable oral ones.

Maintain bed rest during prodromal phases or auras.

During seizures: turn head to side, suction airway if needed, provide support.

Avoid restraints.

Monitor AED levels, side effects, seizure frequency.

Promote Airway Clearance:

Position patient flat, lying down.

Turn head to the side during seizure.

Loosen tight clothing around neck, chest, abdomen.

Suction airway as required.

Administer supplemental oxygen or assist ventilation postictally.

Improve Self-Esteem:

Assess factors contributing to low self-esteem.

Avoid overprotection; encourage independence within safety.

Support activities; consider family attitudes and capabilities.

Help patients understand their feelings are normal, discourage guilt/blame.

Enforce Education About the Disease:

Review epilepsy pathology and prognosis.

Emphasize lifelong treatment needs.

Identify triggers (lights, hyperventilation, noise, screens).

Stress oral hygiene and dental care importance.

Educate on medication regimen, adherence, and not stopping without doctor.

Provide clear missed dose instructions.

Seizure Documentation:

Maintain detailed seizure records: onset, duration, characteristics.

Note behavior or aura changes.

Family Education and Support:

Educate family on first aid, safety measures for seizures.

Offer emotional support and counseling.

Regular Neurological Assessments: Routine monitoring of seizure patterns and neurological status.

Medication Administration: Ensure proper AED administration, dosage, adherence.

Lifestyle Modifications: Collaborate with patient on lifestyle trigger management, consistent sleep, stress reduction.

Emergency Preparedness: Equip caregivers to handle emergencies, guidance on seeking medical help.

Social Integration: Assist patient in social integration, address stigma.

FEBRILE CONVULSIONS

Febrile seizures, or fever fits, are seizures occurring in young children specifically triggered by a high body temperature, in the absence of underlying serious health conditions.

Key Features:

Age Group: Primarily affect children between 6 months and 5 years old.

Short Duration: Typically last less than five minutes.

Rapid Recovery: Children usually return to their normal state within 60 minutes after a seizure.

Causes:

Genetic Predisposition: Family history of febrile seizures is a risk factor.

High Fever Trigger: Linked to body temperatures above 38°C (100.4°F), often due to viral illnesses. Seizure risk increases with higher temperatures.

Vaccines (Small Risk): Some vaccines have a very small associated risk, including MMRV, DTaP-IPV/Hib, and others.

Types of Febrile Seizures:

Simple Febrile Seizures:

Short duration (under 15 minutes).

No focal (localized) features.

Usually a single tonic-clonic seizure within 24 hours.

Complex Febrile Seizures:

Longer duration (over 15 minutes).

Multiple seizures within 24 hours.

May have focal features (e.g., localized twitching).

Febrile Status Epilepticus:

Prolonged seizure lasting more than 30 minutes.

Occurs in a small percentage (up to 5%) of febrile seizure cases.

Diagnosis:

Clinical Diagnosis: Primarily based on clinical presentation and history. Serious underlying causes like meningitis, encephalitis must be ruled out.

Limited Investigations: Blood tests, brain imaging, EEG are usually not required in typical cases.

Rule Out Other Causes: Confirm absence of brain infection, metabolic issues, and prior seizures unrelated to fever.

Management:

First Aid During Seizure:

Ensure a safe environment, remove hazards.

Do not restrain the child.

Note the seizure duration.

Medical Intervention:

No routine use of anti-seizure or anti-fever medications for simple febrile seizures.

Benzodiazepines (e.g., lorazepam) may be given if seizure lasts over five minutes.

Treatment Actions:

Maintain a calm environment.

Time seizure start, call ambulance if >5 minutes.

Place child on protected surface.

Do not restrain; position on side to prevent choking.

Seek immediate medical attention if first seizure or concerning symptoms.

IV lorazepam for prolonged seizures in medical setting.

Prevention:

Fever Management: Prompt and effective management of fever in children.

Avoid Overheating Babies: Prevent excessive heat exposure in infants.

Get in Touch

(+256) 790 036 252

(+256) 748 324 644

Info@nursesonlinediscussion.com

Kampala ,Uganda

© 2025 Nurses online discussion. All Rights Reserved Design & Developed by Opensigma.co