Eye Conditions

Subtopic:

Strabismus

Strabismus, frequently called “crossed eyes” or “squint,” is a visual condition defined by ocular misalignment.

In individuals experiencing strabismus, the eyes fail to maintain proper alignment with one another, meaning they deviate and point in different directions simultaneously. While one eye focuses straight ahead on a target, the other eye may turn or wander:

Inward (converge)

Outward (diverge)

Upward (sursumverge)

Downward (deorsumverge)

This lack of parallel gaze can be either constant, present at all times, or intermittent, occurring only some of the time.

Strabismus is often described using various informal terms such as:

Cross-eyed

Eyes that are crossed

Cockeye

Weak eye

Wall-eyed

Wandering eyes

Eye turn

Strabismus can affect individuals across all age ranges, yet it is most commonly diagnosed and develops during early childhood. Estimates suggest that strabismus affects approximately 4% of children.

If strabismus remains without intervention, it can lead to several vision-related complications, including:

Impaired Depth Perception: Reduced ability to judge distances and perceive the three-dimensional layout of space.

Diplopia (Double Vision): Seeing two images of a single object, as the misaligned eyes send conflicting visual information to the brain.

Amblyopia (Lazy Eye): A condition where the brain starts to favor the stronger, straighter eye and suppresses the visual input from the misaligned eye, potentially leading to reduced vision in the weaker eye if untreated.

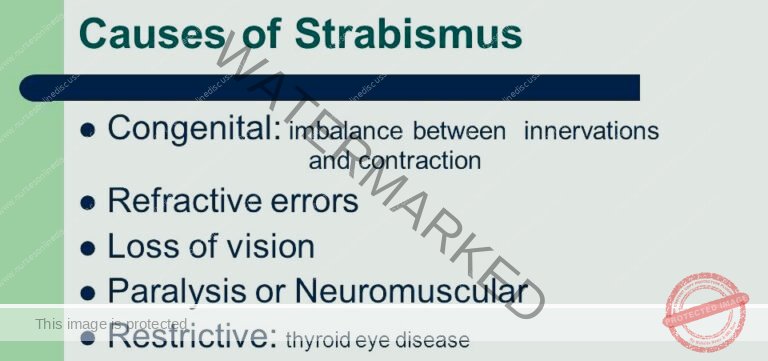

Causes of Strabismus

In many instances, childhood strabismus arises without a clearly identifiable cause. However, a familial tendency suggests a genetic influence. Identifiable causes of strabismus can be grouped into several key categories:

A. Muscular Factors: Issues related to the eye muscles themselves.

Extraocular Muscle Imbalance: Strabismus can be a result of imbalance or weakness in the extraocular muscles. These muscles are responsible for controlling eye movement. An imbalance prevents the eyes from coordinating their movements properly, leading to misalignment.

Restrictive Eye Muscle Disorders: Conditions that physically limit the movement of eye muscles can cause strabismus. Examples include:

Thyroid Eye Disease: This condition can cause inflammation and tightening of eye muscles, restricting their movement.

Orbital Fractures: Fractures of the bony socket surrounding the eye can entrap or damage eye muscles, limiting motion.

B. Nervous System Factors: Issues related to the nerves controlling eye movement and brain control.

Nerve Dysfunction: Strabismus can occur due to problems with the nerves that control the eye muscles. If the nerve signals are disrupted or abnormal, it can impair coordination between the eyes.

Neurological Disorders: Certain conditions affecting the nervous system can impact eye movement control and lead to strabismus. These include:

Cerebral Palsy: A group of disorders affecting movement and muscle tone, often impacting eye control.

Stroke: Disruption of blood supply to areas of the brain controlling eye movement can result in strabismus, especially in adults.

Brain Tumors: Tumors in specific brain regions can compress or interfere with pathways controlling eye movements.

Stroke (Adults): Stroke is a significant cause of acquired strabismus in adults. Damage to brain areas controlling eye muscles can result in sudden onset misalignment.

C. Refractive Errors: Vision problems requiring corrective lenses.

Myopia (Nearsightedness): Severe nearsightedness can sometimes contribute to the development of strabismus, especially in children. The exact mechanism is complex but may involve excessive focusing effort.

Hyperopia (Farsightedness): Uncorrected or significantly imbalanced farsightedness is a more common refractive error linked to strabismus, particularly convergent strabismus (eyes turning inward – esotropia). The eye may over-focus to compensate for farsightedness, which can lead to eye crossing over time.

D. Other Factors: Miscellaneous causes beyond muscle, nerve, or refractive issues.

Congenital Strabismus: Some individuals are born with strabismus. This form is often attributed to:

Genetic factors: Inherited predispositions.

Developmental factors: Issues during eye or brain development in utero.

Eye Injuries or Trauma: Physical trauma to the eye or the muscles around the eye can directly damage eye muscles or nerves, potentially leading to strabismus.

Graves’ Disease (Thyroid Eye Disease): In Graves’ disease, an autoimmune condition causing thyroid hormone overproduction, the muscles and tissues around the eyes can be affected. This can lead to restrictive strabismus due to muscle enlargement and stiffness.

Risk/Predisposing Factors for Strabismus

Several factors can increase the likelihood of developing strabismus:

Family History:

Genetic Component: Strabismus tends to occur more frequently in families, strongly suggesting a genetic predisposition. Having a family member with strabismus significantly increases an individual’s risk.

Age and Development:

Early Childhood Vulnerability: Strabismus commonly manifests during infancy or early childhood. This is the critical period when the visual system, including eye muscle control and binocular vision, is still rapidly developing. Disruptions during this phase are more likely to lead to strabismus.

Medical Conditions: Certain pre-existing medical conditions are associated with a higher incidence of strabismus:

Neurological Disorders: Conditions affecting the brain and nervous system increase risk:

Cerebral Palsy

Down Syndrome

Hydrocephalus (accumulation of fluid in the brain)

Prematurity: Premature birth is a significant risk factor. Premature infants have a higher chance of developing strabismus compared to babies born at full term, possibly due to incomplete development of visual pathways and eye muscle control systems.

Refractive Errors: Uncorrected or significant vision problems:

Uncorrected Hyperopia (Farsightedness)

High Myopia (Nearsightedness)

Anisometropia (unequal refractive power between the two eyes)

Significant refractive errors can strain the visual system and disrupt the normal coordination of eye alignment, contributing to strabismus.

Other Factors: Additional less direct risk factors:

Eye Muscle Imbalance: Even subtle pre-existing imbalances in the strength or coordination of eye muscles can make an individual more susceptible to developing strabismus, especially under visual stress.

Visual Stress/Strain: While not a direct cause, prolonged or intense close-up visual activities, such as:

Excessive screen time on devices (tablets, phones, computers).

Extended periods of reading, especially in poor lighting or at very close distances.

These activities may potentially contribute to strabismus development in individuals who are already susceptible due to other risk factors, by placing strain on the visual system and eye muscles. However, the link is not definitively proven and is an area of ongoing research.

Pathophysiology of Strabismus

The development of strabismus is linked to issues with the extraocular muscles, certain cranial nerves, and the visual cortex of the brain.

Extraocular Muscles: These muscles are responsible for eye movement and alignment. Dysfunction in these muscles, or the nerves controlling them, can result in strabismus.

Cranial Nerves: Cranial nerves III (Oculomotor), IV (Trochlear), and VI (Abducens) innervate the extraocular muscles. Damage to cranial nerve III can lead to the eye drifting downwards and outwards. Impairment of cranial nerve IV can cause an upward and slightly inward eye deviation. Paralysis of the sixth cranial nerve (abducens nerve palsy) leads to inward deviation of the eye.

Causes of Nerve Dysfunction: Several factors can impair these nerves, potentially causing strabismus. Elevated intracranial pressure can compress the nerves as they pass near the clivus and brainstem. Trauma during birth, such as neck twisting during forceps delivery, can injure cranial nerve VI.

Visual Cortex Influence: Research indicates that the visual cortex and the signals it receives are involved in strabismus. This suggests strabismus can develop even without direct issues in the cranial nerves or extraocular muscles themselves.

Amblyopia (Lazy Eye): Strabismus is a common cause of amblyopia. Amblyopia develops when the brain starts to favor the input from one eye over the other, resulting in decreased vision in the weaker eye. Strabismus can disrupt normal visual development in early childhood, as the brain learns to process signals from both eyes.

Types of Strabismus

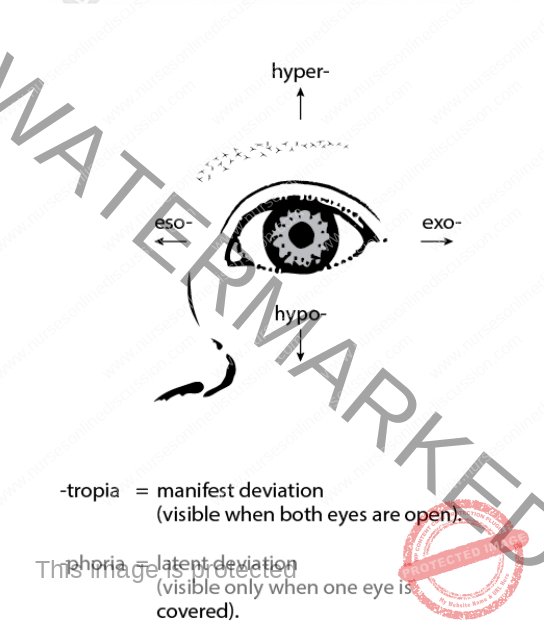

Strabismus is broadly categorized based on the direction of eye misalignment. Two principal types are:

Esotropia:

Definition: Esotropia is defined by the inward turning of one or both eyes. This means that while one eye focuses straight ahead, the other eye deviates towards the nose. It is often referred to as convergent strabismus.

Subtypes of Esotropia: Esotropia is further classified into subtypes based on the age of onset and the underlying reasons for the eye turn:

Infantile Esotropia:

Onset: This subtype is characterized by its early onset, typically appearing within the first six months of life.

Nature of Misalignment: Often, the eye turn is constant, meaning the inward deviation is present most or all of the time from a very young age.

Causation: Infantile esotropia is generally considered to be idiopathic (cause unknown) but may involve subtle neurological or muscular factors present from birth.

Accommodative Esotropia:

Refractive Error Link: This type of esotropia is directly linked to farsightedness (hyperopia).

Mechanism: Children with significant farsightedness must exert extra focusing effort to see clearly at all distances. This focusing effort, known as accommodation, is neurologically linked to convergence (eyes turning inward). In accommodative esotropia, the over-focusing to correct farsightedness inadvertently triggers excessive convergence, leading to eye crossing.

Correction with Glasses: Importantly, accommodative esotropia can often be corrected simply with eyeglasses. The glasses correct the farsightedness, reducing or eliminating the need for excessive focusing and thus reducing or eliminating the inward eye turn.

Sixth Nerve Palsy (Abducens Nerve Palsy):

Neurological Cause: Esotropia can be a direct consequence of damage or paralysis to the sixth cranial nerve (abducens nerve).

Nerve Function: The sixth cranial nerve controls the lateral rectus muscle, which is responsible for outward eye movement.

Effect on Eye Position: When the sixth nerve is impaired, the lateral rectus muscle weakens or becomes paralyzed. This weakness results in the affected eye being unable to move outward properly, leading to an inward eye turn (esotropia) because the opposing medial rectus muscle is no longer balanced by the lateral rectus.

Exotropia:

Definition: Exotropia is characterized by the outward turning of one or both eyes. In this form of strabismus, one eye looks straight ahead while the other deviates away from the nose, towards the side of the head. It is often referred to as divergent strabismus.

Nature of Misalignment: Exotropia can vary in its presentation:

Intermittent Exotropia: The outward eye turn is not always present. It may occur occasionally, particularly when the individual is tired, daydreaming, or not focusing intently on a near target. At other times, the eyes may appear well-aligned.

Constant Exotropia: The outward eye deviation is present consistently, meaning the eye turns out all or most of the time.

Subtypes of Exotropia: Exotropia is further categorized into subtypes, though classifications can overlap:

Intermittent Exotropia: As described above, the eye deviation is not constant, appearing at times of inattention, fatigue, or distance viewing. It’s the most common form of exotropia, especially in children.

Sensory Exotropia: This type develops secondary to significant vision loss in one eye. When one eye has poor vision (e.g., due to cataract, injury, or other eye disease), the brain may begin to suppress the input from that eye, and over time, the eye may drift outward. The poor vision in one eye disrupts the binocular visual system, leading to exotropia.

Divergence Excess Exotropia: In this subtype, the outward deviation is significantly greater when looking at distant objects compared to near objects. When the individual focuses on something far away, the eyes tend to diverge outward excessively. The exotropia may be less apparent when focusing on near targets. The underlying cause is not always clear but may involve issues with the control of eye muscle divergence.

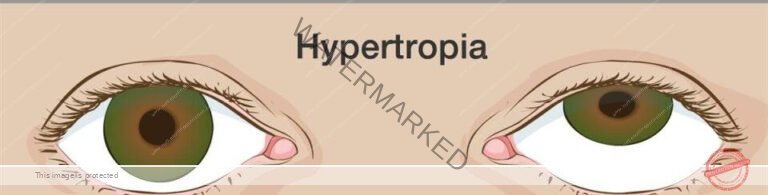

Hypertropia:

Hypertropia is a type of strabismus characterized by one eye deviating upward while the other eye maintains a straight position.

It can be classified as unilateral (affecting one eye) or bilateral (affecting both eyes).

Hypertropia can be caused by various factors, including muscle imbalance, thyroid eye disease,trochlear nerve palsy, nerve palsy, or

mechanical restrictions

Hypotropia:

Definition: Hypotropia is a specific form of strabismus characterized by a downward deviation of one eye in relation to the other eye, which remains in a straight or primary gaze position. In simpler terms, one eye looks correctly forward, while the other eye consistently drifts lower than the straight eye.

Classification: Similar to hypertropia (upward deviation), hypotropia can also be categorized as:

Unilateral Hypotropia: The downward deviation is consistently present in only one eye.

Bilateral Hypotropia: Although less common in pure hypotropia, both eyes could theoretically exhibit a downward tendency, though often one is more prominently deviated.

Underlying Causes: Hypotropia can arise from a variety of factors affecting eye muscle control or mechanics:

Muscle Imbalance: Weakness or overaction of certain extraocular muscles that control vertical eye movements (specifically muscles that elevate the eye).

Nerve Palsy: Damage to or dysfunction of the cranial nerves (especially cranial nerves III and IV) that innervate and control vertical eye muscles can lead to hypotropia.

Mechanical Restrictions: Physical limitations in eye movement, such as tight muscles or tissues around the eye socket, can restrict upward gaze and result in a hypotropic position.

Note on Comitant and Incomitant Strabismus Classification:

Beyond the directional classifications (eso-, exo-, hyper-, hypo-), strabismus can also be described based on the consistency of the misalignment across different gaze directions:

Comitant Strabismus:

Consistent Angle of Deviation: In comitant strabismus, the degree of eye misalignment (angle of deviation) remains relatively constant regardless of which direction the person is looking (up, down, left, right).

Non-Varying: The eye turn is similar whether looking straight ahead, to the side, up, or down.

Typical of Childhood Strabismus: Comitant strabismus is more commonly seen in childhood-onset strabismus.

Incomitant Strabismus:

Variable Angle of Deviation: In incomitant strabismus, the angle of eye misalignment changes depending on the direction of gaze.

Direction-Dependent: The eye turn might be more pronounced or less noticeable when looking in different directions. For example, the misalignment might worsen when looking to the left versus looking to the right.

Often Acquired Strabismus: Incomitant strabismus is frequently associated with acquired strabismus in adults, often resulting from cranial nerve palsies, muscle restrictions (like thyroid eye disease), or neurological conditions. It can also occur in some forms of childhood strabismus.

Clinical Features of Strabismus

Strabismus presents with a range of observable signs and subjective symptoms:

Ocular Misalignment (Deviated Eye Position):

Primary Sign: The most prominent and defining clinical feature of strabismus is visible misalignment of the eyes. This is directly observed as one eye deviating away from the normal, straight-ahead gaze position.

Direction of Deviation: The misalignment can manifest in various directions:

Inward Deviation (Esotropia): Eye turns towards the nose.

Outward Deviation (Exotropia): Eye turns away from the nose.

Upward Deviation (Hypertropia): Eye drifts upwards.

Downward Deviation (Hypotropia): Eye drifts downwards.

Diplopia (Double Vision):

Cause of Double Vision: Strabismus can lead to double vision, also known as diplopia.

Conflicting Visual Input: Diplopia occurs because the misaligned eyes are sending two different and conflicting visual images to the brain simultaneously. The brain struggles to merge these disparate images into a single, clear picture.

Compensatory Head Posture (Head Tilting or Turning):

Compensatory Mechanism: Individuals with strabismus, particularly children, may adopt an abnormal head posture – tilting or turning their head – as a subconscious strategy.

Purpose of Head Tilt/Turn: This head posture is often adopted to:

Attempt to realign the eyes.

Reduce or minimize double vision (diplopia) by positioning the eyes in a way that lessens the misalignment in their primary field of gaze.

Eye Fatigue and Strain (Asthenopia):

Muscular Effort: Strabismus can cause significant eye fatigue and strain.

Constant Muscle Work: The eye muscles are constantly working harder to attempt to compensate for the misalignment and try to achieve single, binocular vision. This extra effort can lead to discomfort and fatigue of the eye muscles, particularly during prolonged visual tasks.

Impaired Depth Perception (Reduced Stereopsis):

Binocular Vision Disruption: Strabismus significantly affects depth perception, making it challenging to accurately judge distances and perceive the world in three dimensions.

Disrupted Binocularity: Normal depth perception (stereopsis) relies on binocular vision, which is the brain’s ability to combine slightly different images from each eye into a single 3D perception. Strabismus disrupts this binocular input, impairing depth judgment.

Amblyopia (Lazy Eye) Development:

Brain Suppression: Strabismus is a major risk factor for developing amblyopia, or “lazy eye.”

Visual Pathway Suppression: To avoid double vision, the brain may begin to actively suppress the visual input from the misaligned eye.

Reduced Visual Acuity: This chronic suppression, especially during critical periods of visual development in childhood, can lead to reduced visual acuity (sharpness) in the suppressed eye. The eye itself may be healthy, but its visual pathway to the brain does not develop properly due to underuse.

Headaches (Ocular Headaches):

Eyestrain Related Headaches: Some individuals with strabismus may experience headaches, particularly after engaging in visually demanding tasks like reading or computer work.

Binocular Strain Contribution: The constant strain on the eye muscles attempting to correct misalignment and the disrupted binocular vision can contribute to the onset of headaches.

Reading Difficulties:

Tracking Challenges: Strabismus can make reading more difficult.

Line Skipping and Place Loss: Eye misalignment can impair the ability to smoothly track lines of text across a page. This can result in:

Skipping lines of text unintentionally.

Frequently losing one’s place while reading.

Experiencing visual disturbances or words appearing to move or blur during reading.

Psychosocial Impact – Self-Esteem Issues:

Social and Emotional Effects: Strabismus can have a significant psychological and social impact, particularly on children.

Self-Consciousness and Embarrassment: The visibly misaligned eyes can cause self-consciousness and embarrassment, especially in children who are more aware of their appearance and peer perceptions.

Social Difficulties: Strabismus can sometimes lead to social difficulties, teasing, or reduced self-esteem, affecting a child’s overall quality of life and confidence.

Diagnosis of Strabismus

Diagnosing strabismus requires a combination of gathering patient information, assessing symptoms, and conducting specific eye examinations to confirm the misalignment and determine its characteristics.

Medical History Collection:

Purpose: To gather essential background information relevant to the potential diagnosis of strabismus. This involves inquiring about:

Patient Symptoms: Detailed questioning about any visual symptoms that suggest strabismus, such as eye crossing, double vision, or reduced depth perception.

Symptom Chronology: Understanding when the symptoms began, how frequently they occur, and if there are any patterns or triggers.

Family History: Detailed family medical history, specifically focusing on any instances of strabismus or other eye conditions within the family, as strabismus has a genetic component.

Underlying Health Conditions: Eliciting information about any pre-existing or concurrent health conditions the patient has. Certain systemic or neurological conditions can be associated with or contribute to strabismus.

Symptom Evaluation:

Purpose: To directly assess and document the patient’s subjective experience and reported symptoms. This includes a careful evaluation of:

“Crossed Eyes” Observation: Inquiring if the patient or family has noticed eye crossing or misalignment.

Diplopia (Double Vision): Determining if the patient experiences double vision, whether constant or intermittent.

Depth Perception Issues: Assessing for any difficulties with depth perception, such as trouble judging distances or clumsiness in visually guided tasks.

Misaligned Eye Appearance and Movement: Evaluating the patient’s description of their eye appearance and any perceived lack of coordinated eye movements.

Visual Acuity Test:

Purpose: To quantitatively measure the sharpness of vision in each eye individually.

Method: Typically performed using a standardized eye chart (like a Snellen chart) with letters or symbols of decreasing size viewed at a set distance. Vision is assessed at both distance and near to get a comprehensive view.

Diagnostic Significance in Strabismus: A visual acuity test helps:

Detect Amblyopia: Identify any reduction in vision in one eye (amblyopia or lazy eye), which can be a consequence of strabismus.

Quantify Vision Changes: Establish a baseline measure of visual acuity to monitor for any changes in vision over time or with treatment.

Cover-Uncover Test:

Purpose: A fundamental test for detecting manifest strabismus (strabismus that is always present).

Procedure: The examiner instructs the patient to fixate on a target.

Cover One Eye: One of the patient’s eyes is gently covered.

Observe Uncovered Eye: The examiner watches the uncovered eye for any movement to take up fixation once the other eye is covered. If the uncovered eye moves to fixate, it indicates that it was not fixating straight ahead before the other eye was covered, suggesting misalignment.

Uncover and Observe Covered Eye: The cover is then quickly removed, and the previously covered eye is observed for any movement as it takes up fixation. Any refixation movement suggests strabismus.

Interpretation: Refixation movements upon covering or uncovering an eye indicate that the eyes are not naturally aligned when both are open and viewing together.

Ocular Alignment and Focus Tests:

Purpose: To comprehensively evaluate the movement, focus, and coordination of both eyes.

Synoptophore Use (Optional): A synoptophore is a specialized ophthalmic instrument that may be used. It allows for:

Binocular Vision Assessment: Testing how the eyes work together as a team (binocularity).

Eye Alignment Measurement: Precisely quantifying the degree and type of eye misalignment.

Fusion Assessment: Evaluating the ability to merge images from both eyes into a single percept.

General Observational Assessment: Even without specialized equipment, careful observation of eye movements during fixation, tracking, and in different gaze positions provides crucial diagnostic information about ocular alignment and coordination.

Refraction Test:

Purpose: To accurately measure the refractive error of each eye. Refractive error refers to how light is focused by the eye and includes conditions like nearsightedness (myopia), farsightedness (hyperopia), and astigmatism.

Tools Used: Refraction is typically performed using:

Phoropter: A device placed in front of the patient’s eyes containing various lenses that are changed systematically. The patient indicates which lenses provide the clearest vision.

Retinoscope: A handheld instrument used by the examiner to objectively assess the eye’s refractive error by observing the reflection of light from the retina.

Diagnostic Significance in Strabismus: Refraction helps:

Identify Refractive Error Contribution: Determine if uncorrected refractive errors, particularly farsightedness, are a contributing factor to the strabismus, as in accommodative esotropia.

Prescribe Corrective Lenses: Determine the appropriate eyeglass prescription to correct refractive errors, which may be a primary treatment for certain types of strabismus or a necessary part of an overall management plan.

Retinal Examination (Ophthalmoscopy):

Purpose: To conduct a detailed examination of the internal structures of the eye, especially the retina (the light-sensitive tissue at the back of the eye) and optic nerve.

Ophthalmoscope Use: An ophthalmoscope, a handheld instrument with a light and lenses, is used to visualize the retina and optic disc.

Diagnostic Significance in Strabismus: Retinal examination helps:

Rule Out Ocular Pathology: Identify or exclude other eye diseases or conditions (like retinal abnormalities, optic nerve issues, cataracts) that could be causing or contributing to the strabismus or its symptoms. It’s essential to differentiate strabismus from other conditions that might mimic it or coexist with it.

Additional Testing (Selective – Based on Clinical Suspicion):

Purpose: To investigate for potential underlying systemic or neurological conditions that might be associated with or causing the strabismus, particularly if the history or eye exam suggests more complex or non-typical strabismus.

Neurological Examination: Neurological exam may be indicated to assess:

Cranial nerve function (especially cranial nerves III, IV, VI which control eye movements).

Motor skills, coordination, and reflexes.

Signs of neurological conditions like cerebral palsy, hydrocephalus, or Guillain-Barré syndrome, which are known risk factors for strabismus.

Brain Imaging (MRI or CT Scan): In certain cases, particularly if neurological findings are present or if a central nervous system cause is suspected, brain imaging studies like MRI or CT scans may be ordered to evaluate the brain and rule out conditions such as brain tumors, hydrocephalus, or nerve compression.

Challenges Faced by People with Strabismus

Living with strabismus presents a unique set of challenges that extend beyond visual impairments, significantly impacting emotional well-being, social interactions, and life opportunities.

Emotional Distress:

Increased Anxiety and Inhibition: Children with strabismus often demonstrate higher levels of inhibited behavior, anxiety, and general emotional distress compared to their peers.

Peer Perception Impact: Negative perceptions from peers regarding their appearance can trigger feelings of embarrassment, anger, and self-consciousness.

Fundamental Impact on Social Communication: These emotional responses can fundamentally impair social communication skills and willingness to engage socially.

Negative Impact on Self-Esteem:

Body Image Concerns: Strabismus can have a detrimental effect on self-esteem due to altered body image and self-perception.

Appearance-Related Self-Consciousness: Individuals may become intensely self-conscious about their eye appearance, leading to constant worry about how others perceive them and judge their looks.

Limited Opportunities (Perceived and Real):

Employment Misconceptions: Strabismus can unfortunately lead to misconceptions in the workplace. Individuals may encounter negative assumptions about their capabilities and work ethic based solely on their eye condition.

Career Limitations: These misconceptions can translate into limited employment opportunities and difficulties in career progression, hindering professional growth and advancement.

Social Stigma and Misconceptions:

Cosmetic Stigma: The visibly misaligned eyes in strabismus can result in significant social stigma.

Negative Stereotypes: Individuals may face negative attitudes and inaccurate stereotypes from society. These can include false assumptions about their:

Intelligence levels.

Trustworthiness.

Overall attractiveness.

Social Isolation and Discrimination: Experiencing this stigma can lead to feelings of social isolation, marginalization, and even discrimination in social and public settings.

Vision Difficulties and Related Symptoms:

Functional Vision Problems: Strabismus directly causes various vision-related problems that can impact daily life:

Double vision (diplopia).

Difficulties with reading and tracking text.

Eye strain and fatigue.

Headaches, particularly after visual tasks.

Impaired Depth Perception: The misalignment disrupts depth perception, making it challenging to judge distances and navigate environments safely and confidently.

Visual Coordination Challenges: Reduced visual coordination impacts everyday tasks requiring precise hand-eye coordination and visual attention.

COPING MECHANISMS TO STRESS FROM HAVING STRABISMUS

Individuals with strabismus develop various coping strategies to manage the stress and challenges associated with their condition. Research categorizes these coping methods into three main subcategories:

Avoidance-Based Coping:

Limiting Social Participation: Some individuals cope by avoiding situations or activities where they feel their strabismus might be noticeable or draw unwanted attention.

Reduced Engagement in Visual Activities: They may refrain from participating in activities that require sustained eye contact or visual focus, if they believe it highlights their condition negatively.

Goal: The primary goal is to minimize exposure to perceived negative social evaluation or scrutiny related to their eye misalignment.

Distraction-Based Coping:

Shifting Focus Away from Condition: This involves actively redirecting attention away from their strabismus and the associated stress.

Emphasis on Other Life Aspects: Individuals may deliberately focus on other aspects of their life that are positive and unrelated to their condition, such as hobbies, work, or relationships, as a way to cope.

Engagement in Distracting Activities: Engaging in distracting activities – hobbies, entertainment, work, or social engagements – serves as a mechanism to take their mind off their condition and reduce focus on self-consciousness or negative thoughts.

Adjustment and Adaptation Coping:

Modifying Task Approach: This coping style involves adapting the way they approach activities to accommodate their visual condition and any associated limitations.

Finding Alternative Strategies: Individuals may actively seek and implement alternative methods to accomplish tasks that are challenging due to strabismus-related vision difficulties (like depth perception issues or reading difficulties).

Situational Adaptation: They learn to adapt to different situations and environments, developing strategies to minimize the impact of their condition on their daily functioning and participation. For example, adjusting lighting for reading, or positioning themselves in social situations to feel more comfortable.

Management of Strabismus

Treatment for strabismus is varied and depends on the specific type, severity, and underlying cause of the eye misalignment.

Aims of Management: The overarching goals of strabismus treatment are to:

Enhance Ocular Alignment and Coordination: To improve how the eyes work together, achieving better parallelism and synchronized movement.

Prevent Visual Complications: To avert potential long-term visual problems that can arise from untreated strabismus, such as amblyopia (lazy eye) and persistent double vision.

Optimize Visual Development: Especially in children, to support and encourage the best possible development of binocular vision and visual acuity.

Treatment Modalities:

Eyeglasses (Corrective Lenses):

Application: In specific instances, strabismus can be effectively managed or significantly improved simply by wearing eyeglasses.

Mechanism of Action: This approach is particularly beneficial when strabismus is associated with refractive errors like nearsightedness or farsightedness. Corrective lenses work by:

Sharpening visual focus, addressing blurriness caused by the refractive error.

Reducing the need for excessive eye focusing effort, especially in cases of accommodative esotropia linked to farsightedness. By correcting farsightedness, eyeglasses can lessen the over-convergence that causes the eyes to cross inward.

In cases of anisometropia (unequal refractive error between eyes), glasses ensure each eye receives a clear image, promoting better binocular vision.

Patching or Eye Drops (Occlusion Therapy):

Purpose: Patching therapy (covering the stronger eye with a patch) or using specialized eye drops (to blur vision in the stronger eye) is often prescribed to treat amblyopia (lazy eye) that frequently accompanies strabismus.

Mechanism of Action (Occlusion Therapy): These methods, collectively known as occlusion therapy, are designed to:

Strengthen the Weaker Eye: Force the less-used, weaker eye (the amblyopic eye) to work harder. By blocking or blurring the vision of the stronger, preferred eye, the brain is compelled to rely more on the weaker eye for visual input.

Improve Visual Development: Encourage the visual pathways and visual cortex associated with the weaker eye to develop more fully and improve in function.

Indirectly Improve Alignment: While primarily for amblyopia, improving vision in the weaker eye can sometimes also have a positive secondary effect on eye alignment.

Vision Therapy (Orthoptics):

Nature of Therapy: Vision therapy encompasses a structured program of eye exercises and visual activities.

Goals: The aim of vision therapy is to:

Enhance Eye Coordination: Improve the ability of both eyes to work together smoothly as a team.

Strengthen Eye Muscles: Improve the strength and control of the eye muscles responsible for alignment and movement.

Improve Binocular Vision Skills: Enhance various aspects of binocular vision, including fusion (merging images from both eyes) and stereopsis (depth perception).

Adjunctive Therapy: Vision therapy is often used in combination with other strabismus treatments, such as eyeglasses or surgery, to maximize outcomes.

Specific Strabismus Types: It can be particularly beneficial for certain types of strabismus, especially intermittent exotropia and convergence insufficiency (difficulty turning the eyes inward for near tasks).

Prisms in Eyeglasses:

Specialized Lenses: Prisms are incorporated into eyeglasses as specialized lenses designed to alter the way light enters the eye.

Mechanism of Action: Prisms work by:

Bending Light Rays: Prisms bend incoming light rays before they reach the eye.

Redirecting Image to Retina: This bending of light effectively redirects the visual image to fall on the correct position on the retina in each eye, even when the eyes are misaligned.

Reducing Double Vision: By realigning the perceived visual images, prisms can help to reduce or eliminate double vision (diplopia) and improve visual comfort.

Use Cases: Prisms are useful for correcting small to moderate degrees of strabismus and are often employed to manage diplopia and improve binocular vision in certain cases.

Botulinum Toxin (Botox) Injections:

Procedure: Involves injecting Botulinum toxin (Botox) directly into a specific extraocular muscle.

Mechanism of Action: Botox works by:

Temporary Muscle Weakening: Causing temporary and partial paralysis or weakening of the injected eye muscle.

Rebalancing Eye Muscles: By weakening an overactive or stronger muscle, Botox can allow the opposing muscle to become relatively stronger, potentially improving eye alignment by rebalancing muscle forces.

Limited Applications: Botox injections are typically reserved for:

Certain Types of Strabismus: Often used for specific types of strabismus, such as acute-onset sixth nerve palsy or some forms of comitant esotropia in children.

Temporary Measure: As Botox effects are temporary, lasting several weeks to months, it’s often used as a temporary measure, either to see if alignment can be improved or as a step before considering surgical intervention.

Repeat Injections: The treatment effect is not permanent; injections may need to be repeated every few months (typically every 3-4 months) as the muscle function gradually recovers from the toxin’s effects.

Eye Muscle Surgery (Strabismus Surgery):

Surgical Intervention: Eye muscle surgery is a common and effective surgical procedure for correcting strabismus.

Indications: Surgery is often recommended for:

Persistent Strabismus: Cases where non-surgical treatments (glasses, patching, prisms, Botox) have not adequately corrected the misalignment.

Severe Strabismus: Significant degrees of eye misalignment.

Procedure Details: During surgery, a pediatric ophthalmologist or strabismus surgeon performs precise adjustments to the extraocular muscles. This involves:

Muscle Strengthening (Resection): Resecting (shortening) and reattaching a weaker muscle to increase its pulling power.

Muscle Weakening (Recession): Recessing (moving the insertion point further back on the eye) of a stronger muscle to reduce its pulling force.

Goal of Surgery: The overall aim is to rebalance the tension of the eye muscles to achieve improved and more natural eye alignment.

Anesthesia and Recovery: The surgery is typically performed under general anesthesia, especially in children.

Multiple Surgeries Possible: Depending on the complexity of the strabismus and the individual response, more than one surgery may be necessary to achieve optimal eye alignment and binocular vision.

Nursing Diagnoses (Examples Related to Strabismus):

Risk for Injury related to impaired sensory function.

Evidence: The lack of coordinated eye movements in strabismus leads to visual disturbances like double vision and blurry vision, and reduced depth perception. These visual impairments can compromise spatial awareness and increase the risk of accidents and injuries due to misjudging distances or failing to perceive hazards in the environment.

Disturbed Sensory Perception related to structural damage.

Evidence: Strabismus, by definition, involves a structural issue in the visual system, specifically a lack of coordination between the extraocular muscles. This structural abnormality disrupts the normal processing of visual information, resulting in distorted sensory perception. This distortion manifests as double vision (diplopia), blurred vision, and impaired depth perception, indicating a disturbance in how visual sensory input is perceived and interpreted by the brain.

Knowledge Deficit related to impaired vision.

Evidence: Children newly diagnosed with strabismus, and their families, often have a limited understanding of the condition itself. This includes a lack of knowledge about:

The nature of strabismus.

Available treatment options.

The critical importance of early intervention to prevent vision loss (amblyopia) and maximize visual outcomes. This lack of understanding constitutes a knowledge deficit that needs to be addressed through education.

Social Isolation related to limited ability to participate in activities and impaired vision.

Evidence: Strabismus and its associated visual problems can limit a child’s ability to engage fully in social interactions and various activities. Vision impairment can make it challenging to participate in:

Sports and physical activities requiring good depth perception and hand-eye coordination.

Social games and interactions that rely on typical visual cues.

Classroom activities that involve reading and visual tasks.

These limitations in participation and potential self-consciousness about appearance can contribute to social isolation and reduced peer interaction.

Impaired Parent-Child Interaction related to the child’s visual impairment.

Evidence: A child’s visual impairment from strabismus can affect the typical patterns of parent-child interaction and communication. Parents may require:

Additional education to understand the specific visual needs of their child.

Guidance on how to effectively communicate and engage with a child who has visual challenges.

Support in adapting play, learning, and daily routines to accommodate the child’s visual impairment and promote optimal development. Without appropriate understanding and adaptation, the quality of parent-child interaction may be negatively impacted.

Get in Touch

(+256) 790 036 252

(+256) 748 324 644

Info@nursesonlinediscussion.com

Kampala ,Uganda

© 2025 Nurses online discussion. All Rights Reserved Design & Developed by Opensigma.co