Eye Conditions

Subtopic:

Glaucoma

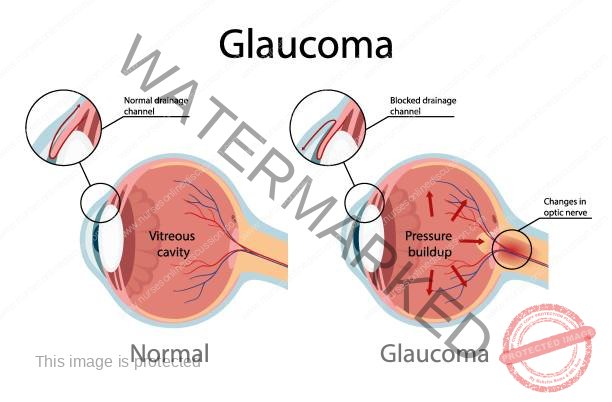

Glaucoma is a category of eye conditions distinguished by unusually elevated pressure inside the eye (intraocular pressure), damage to the optic nerve, and a decrease in peripheral vision.

Glaucoma encompasses various eye diseases that lead to damage of the optic nerve and subsequent loss of vision, primarily caused by elevated intraocular pressure (IOP).

It is a significant contributor to blindness across the globe.

Glaucoma develops due to increased pressure within the eye (IOP). This elevated pressure stems from either a structural abnormality or a functional problem within the eye’s drainage system.

The primary reason for the damage to the optic nerve in glaucoma is elevated intraocular pressure (IOP). This excessive fluid pressure inside the eye can arise from various factors, such as a blockage in the drainage channels or a narrowing or complete closure of the angle where the iris and cornea meet (the iridocorneal angle).

Typical intraocular pressure ranges from 12 to 21 millimeters of mercury (mm Hg). In glaucoma, this pressure increases, leading to compression of the retina (the light-sensitive layer at the back of the eye) and the optic nerve (which transmits visual information to the brain). If left untreated, this compression causes a gradual and irreversible loss of vision.

INCIDENCE

Globally, between 6 to 67 million individuals are affected by glaucoma. It is more prevalent in people over the age of 40.

Glaucoma is often referred to as the “silent thief of sight” because the vision loss it causes typically progresses gradually and painlessly over an extended period. Worldwide, after cataracts, glaucoma is the second most common cause of blindness.

EYE ANATOMY( Click here for eye anatomy)

Normal Pathway of Aqueous Humor

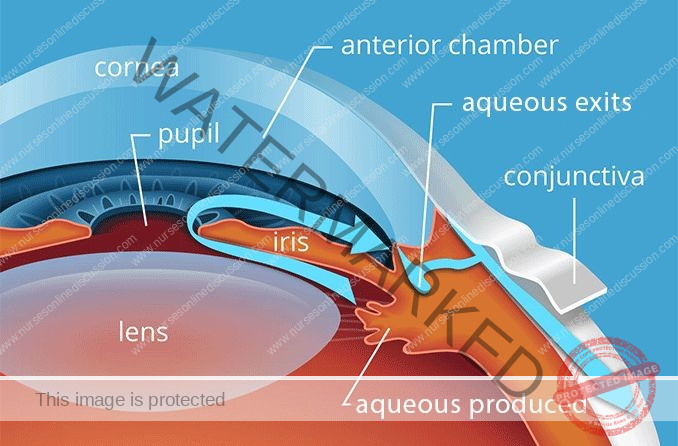

Aqueous fluid Circulation:

The aqueous fluid is a clear fluid produced in the ciliary body. From there, it flows out, passing through the iris, lens, pupil, cornea, anterior chamber, and trabecular meshwork, eventually reaching the Schlemm’s canal.

This aqueous fluid nourishes the cornea and lens.

The eye maintains an internal fluid circulation system where:

Fluid is generated at the base of the iris.

This fluid then moves through the pupil to the front of the iris.

Finally, the fluid leaves the eye at the angle formed between the iris and the cornea, draining through a porous tissue known as the trabecular meshwork.

The intraocular pressure (IOP) is determined by:

The rate at which aqueous fluid is produced in the ciliary body.

The resistance encountered by the aqueous fluid as it flows out through the drainage passages.

Causes/ Aetiology of Glaucoma

Glaucoma is a chronic eye disease that can lead to vision loss and blindness. The causes can be broadly categorized into primary and secondary.

Primary Causes of Glaucoma:

These refer to the underlying mechanisms or conditions that directly lead to the development of glaucoma:

Increased Eye Pressure: A key factor is elevated pressure inside the eye. This occurs when there is an issue with the eye’s drainage system, causing the fluid within the eye to accumulate and exert excessive pressure, ultimately damaging the optic nerve.

Optic Nerve Damage: Glaucoma is characterized by damage to the optic nerve. While the exact reasons for this damage are not fully understood, it is strongly linked to increased eye pressure.

Fluid Buildup: The aqueous humor, the fluid inside the eye, may not drain properly due to a malfunction within the eye’s drainage system. This impaired drainage leads to a gradual increase in intraocular pressure, resulting in glaucoma.

Secondary Causes of Glaucoma:

These refer to underlying conditions or factors that contribute to the development of glaucoma:

Angle-Closure Glaucoma: This type of glaucoma occurs when the iris protrudes forward, partially or completely blocking the drainage angle. This blockage prevents the aqueous humor from circulating properly, leading to a rapid increase in eye pressure.

Normal-Tension Glaucoma: In this form of glaucoma, optic nerve damage occurs even when the eye pressure is within the normal range. The precise cause is unknown, but factors like reduced blood flow to the optic nerve are suspected to play a role.

Glaucoma in Children: Children can be born with glaucoma (congenital glaucoma) or develop it in their early years (juvenile glaucoma). This can be caused by blocked drainage pathways, eye injury, or other underlying medical conditions.

Pigmentary Glaucoma: In this condition, pigment granules shed from the iris can accumulate and obstruct or slow down the drainage of aqueous humor from the eye, leading to elevated eye pressure.

Inflammation of the Middle Layer of the Eye: Uveitis, an inflammation of the uvea (the middle layer of the eye which includes the iris, ciliary body, and choroid), can lead to uveitic glaucoma.

Risk Factors for Glaucoma:

These are factors that increase the likelihood of developing glaucoma:

High Internal Eye Pressure: Elevated intraocular pressure is a significant risk factor for glaucoma.

Age: The risk of glaucoma increases with age, particularly for those over 60.

Ethnicity: Individuals of Black, Asian, or Hispanic heritage have a higher risk of developing glaucoma.

Family History: Having a close relative (parent, sibling) with glaucoma increases an individual’s risk.

Medical Conditions: Certain health conditions, such as diabetes, migraines, high blood pressure, and sickle cell anemia, are associated with an increased risk of glaucoma.

Thin Corneas: Having a thinner-than-average cornea is linked to a higher risk of glaucoma.

Extreme Nearsightedness or Farsightedness: Individuals with significant myopia (nearsightedness) or hyperopia (farsightedness) have an elevated risk.

Eye Injury or Surgery: Past eye injuries or certain types of eye surgery can increase the risk of developing glaucoma.

Long-term Use of Corticosteroid Medications: Prolonged use of corticosteroid medications, especially eye drops, can increase the risk of glaucoma.

Pathophysiology of Glaucoma

The underlying cause of open-angle glaucoma remains unclear.

Excess production of aqueous humor, and decreased outflow of aqueous humor, are the key factors in the pathophysiology of glaucoma.

Excess production of aqueous humor can occur, leading to an increase in intraocular pressure. Additionally, there may be a decrease in the outflow of aqueous humor due to blockage or

narrowing of the drainage pathways.

The increased intraocular pressure puts pressure on the optic nerve, compromising its blood supply and leading to ischemia. The optic nerve is responsible for transmitting visual

information from the eye to the brain. When the optic nerve is damaged, it can result in the loss of vision

Diagnosis of Glaucoma

Screening for glaucoma is typically included as a routine part of a comprehensive eye examination conducted by optometrists and ophthalmologists.

History taking: When assessing for glaucoma, the eye care professional will pay close attention to factors such as the patient’s sex, race, medication history, refractive error (nearsightedness, farsightedness, astigmatism), and any family history of glaucoma or other eye conditions.

Glaucoma tests:

Tonometry: This test measures the pressure inside your eye, known as the intraocular pressure (IOP). To perform this, the eye care provider will first numb your eye with eye drops. Then, using an instrument called a tonometer, they will measure the pressure. This can be done either by gently blowing a puff of warm air onto the surface of the eye or by using a small, specialized tool that makes gentle contact with the eye.

Gonioscopy: This procedure allows the eye doctor to examine the angle where the iris (the colored part of your eye) meets the cornea (the clear front surface of your eye). Numbing eye drops are administered, and then a special hand-held contact lens with a built-in mirror is carefully placed on the eye’s surface. This lens enables the doctor to directly visualize the drainage angle and check if it’s open or blocked.

Ophthalmoscopy (Dilated Eye Examination): This test focuses on examining the optic nerve at the back of your eye, assessing its shape and color for any signs of damage. Eye drops are used to widen (dilate) the pupil, which makes it easier for the examiner to get a clear view. They then use a magnifying device with a bright light to inspect the optic nerve.

Perimetry (Visual Field Test): This test maps out your entire range of vision, both your central and peripheral (side) vision. You will be asked to look straight ahead while small light spots are flashed in different areas of your visual field. By responding when you see the lights, a map of your vision is created to identify any areas of vision loss.

Pachymetry: This test measures the thickness of your cornea. A specialized instrument called a pachymeter is gently placed on the front surface of your eye to obtain this measurement. Corneal thickness can influence IOP readings, so this test helps in accurately interpreting the pressure within your eye.

Nerve Fiber Analysis: These advanced imaging techniques provide a detailed assessment of the retinal nerve fiber layer, which is often affected by glaucoma. Methods like optical coherence tomography (OCT), scanning laser polarimetry (GDx), and scanning laser ophthalmoscopy (SLO) can precisely measure the thickness of this nerve layer, helping to detect early signs of damage.

Classification of Glaucoma

Glaucoma is broadly categorized into specific types, each with its own characteristics and underlying mechanisms.

Congenital Glaucoma

Congenital glaucoma is a rare form of glaucoma that is present at birth or develops shortly thereafter. It is characterized by abnormalities in the anterior chamber angle that obstruct the outflow of aqueous humor, leading to increased intraocular pressure and potential damage to the optic nerve. Congenital glaucoma can manifest at different stages: at birth (True Congenital), before 3 years of age (Infantile), or between 3 and 16 years of age (Juvenile).

Clinical Features of Congenital Glaucoma:

Age of onset: Typically presents in infants and young children, usually before the age of 3 years.

Triad of symptoms: The classic signs are:

Watering (epiphora): Excessive tearing or watery eyes.

Photophobia: Sensitivity to light.

Blepharospasm: Involuntary contraction or twitching of the eyelids.

Buphthalmos: Congenital glaucoma can cause enlargement of the eyeball, known as buphthalmos or “ox eye” or “bull’s eye.” This occurs due to increased intraocular pressure (IOP) and the rapid expansion of the developing eye.

Corneal changes: The elevated IOP in congenital glaucoma can lead to corneal enlargement and clouding. This can result in corneal edema and opacification, which may cause visual impairment.

Haab striae: Horizontal or oblique breaks in Descemet’s membrane, known as Haab striae, can be seen in congenital glaucoma. These striae are a result of the stretching of the cornea due to increased IOP.

Optic nerve damage: If left untreated or uncontrolled, congenital glaucoma can lead to optic nerve damage, resulting in vision loss.

Variable presentation: The severity and presentation can vary. Some cases may be unilateral (affecting one eye), while others may be bilateral (affecting both eyes).

Blepharospasm (involuntary forceful closure of eyes): A common clinical feature involving the involuntary and forceful closure of the eyelids.

Excessive lacrimation: Increased tearing is another common symptom as the increased pressure in the eye can cause the tear ducts to produce more tears than usual.

Enlarged and edematous cornea: The cornea can become enlarged and swollen due to fluid accumulation, leading to cloudiness and a loss of transparency.

Thin and blue sclera: The sclera may appear thinner and have a bluish hue due to the visibility of the underlying choroid layer through the stretched sclera.

Deep anterior chamber: The space between the cornea and the iris can become deeper as the increased pressure pushes the iris backward.

Flat lens: The lens of the eye may appear flatter than normal, affecting the eye’s focusing ability.

Optic disc atrophy: Degeneration and loss of nerve fibers in the optic disc can occur due to the increased pressure damaging the optic nerve.

Management of Congenital Glaucoma:

The primary goals are to lower intraocular pressure (IOP) and prevent further damage to the optic nerve.

Medical Therapy: Often used temporarily to control IOP and clear corneal clouding before surgery. Medications may include topical beta-blockers (e.g., timolol, betaxolol), prostaglandin analogs, and carbonic anhydrase inhibitors.

Surgical Interventions:

Angle Surgery: The primary treatment to improve aqueous outflow and lower IOP.

Goniotomy: An incision is made in the trabecular meshwork to improve drainage.

Trabeculotomy: The trabecular meshwork is incised to create a new drainage pathway.

Trabeculectomy: If angle surgery is unsuccessful, a new drainage channel is created to bypass the trabecular meshwork.

Glaucoma Implant Surgery: Used when other surgical options fail, involving the placement of a drainage device (e.g., Molteno, Baerveldt, or Ahmed implant) to regulate aqueous humor flow and lower IOP.

Follow-up and Monitoring: Regular visits with an ophthalmologist are crucial to monitor IOP, assess treatment effectiveness, and detect any complications or disease progression. Ongoing management may involve medication adjustments, further surgery if needed, and monitoring for long-term issues like refractive errors or amblyopia (“lazy eye”).

ACQUIRED GLAUCOMA

Acquired glaucoma develops later in life due to various factors such as age, genetics, underlying medical conditions, or trauma. It is a chronic and progressive condition requiring ongoing management to control IOP and preserve vision.

It is further divided into:

PRIMARY GLAUCOMA

Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma (POAG)

Primary Angle-Closure Glaucoma (PACG)

Chronic Angle-Closure Glaucoma

SECONDARY GLAUCOMA

Lens-Induced Glaucoma

Glaucoma due to Uveitis

Neovascular Glaucoma

Glaucoma Associated with Intraocular Tumor

Steroid-Induced Glaucoma

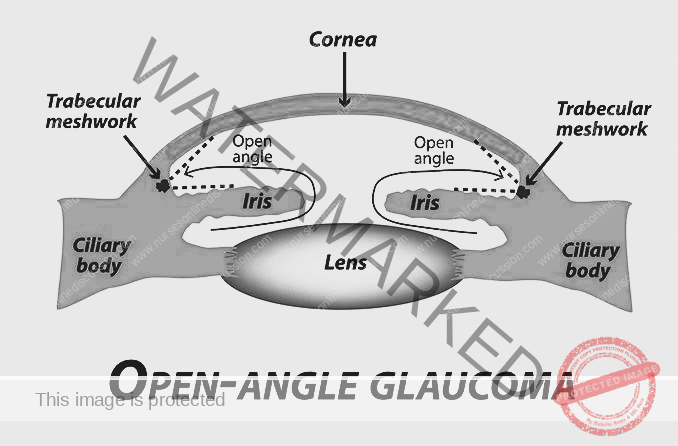

PRIMARY OPEN-ANGLE GLAUCOMA (POAG)

Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma (POAG), also known as open-angle glaucoma, chronic simple glaucoma, or simple complex glaucoma, results from the overproduction of aqueous humor that encounters resistance as it attempts to flow out through the trabecular meshwork. This leads to increased intraocular pressure (IOP) and subsequent damage to the optic nerve, ultimately causing vision loss.

In POAG, there is no physical narrowing of the anterior chamber angle. Instead, the resistance within the trabecular meshwork itself impedes the outflow of aqueous humor. This results in a gradual increase in IOP, along with characteristic cupping of the optic disc (a change in the appearance of the optic nerve) and visual field defects (loss of peripheral vision).

Predisposing factors for primary glaucoma include:

Cigarette smoking

Diabetes Mellitus

Hypertension

Myopia (nearsightedness)

Old age

Clinical features of primary glaucoma may include:

Asymptomatic in the early stages

Mild headache and pain in the eye

Difficulty in reading

Delayed dark adaptation (taking longer for vision to adjust to darkness)

Alteration in vision (unspecified)

Mild ache in the eyes

Increased IOP (more than 21 mm Hg)

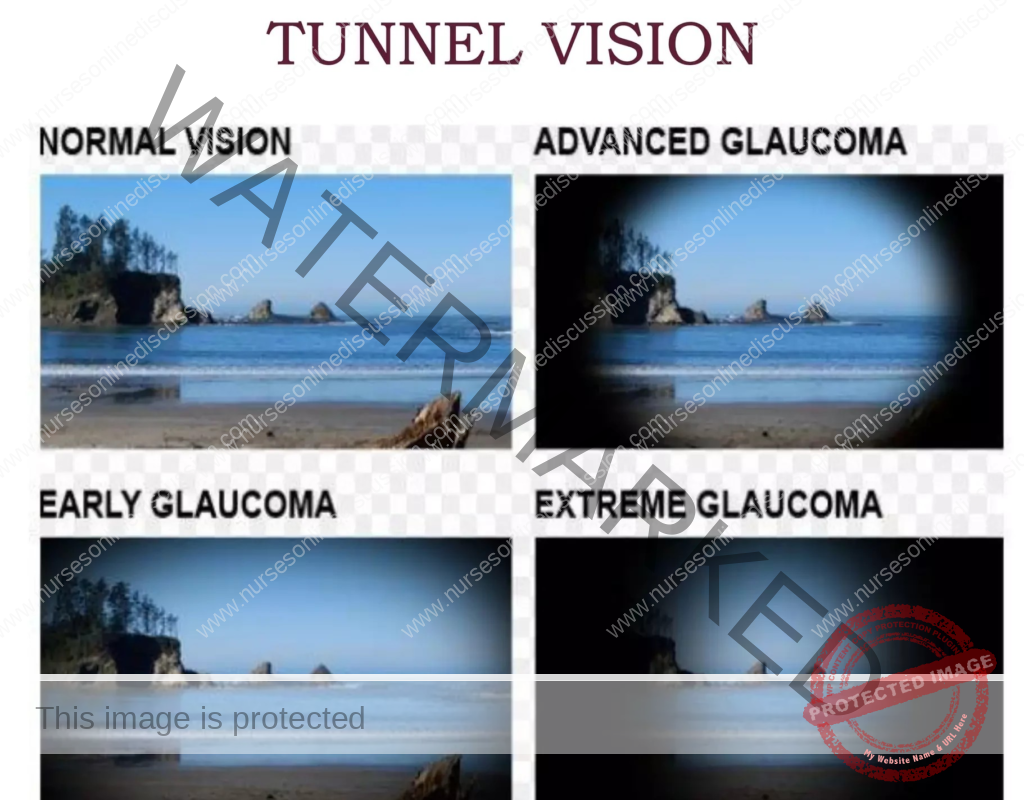

Loss of peripheral vision

Reduced visual acuity at night

Corneal edema (swelling of the cornea)

Visual field deficit

Investigations for primary glaucoma include:

Tonometry: To measure intraocular pressure (IOP). In glaucoma, IOP may be consistently high in later stages and fluctuate in the early stages.

Gonioscopy: To assess the angle of the anterior chamber. While the angle is open in POAG, this test helps rule out angle-closure glaucoma.

Fundus examination: Using ophthalmoscopy and a slit-lamp biomicroscope to observe changes in the optic disc, such as cupping.

Perimetry: To assess for changes in the visual field, identifying any peripheral vision loss.

Treatment options for primary glaucoma include:

Medical treatment: Typically the first-line approach for open-angle glaucoma.

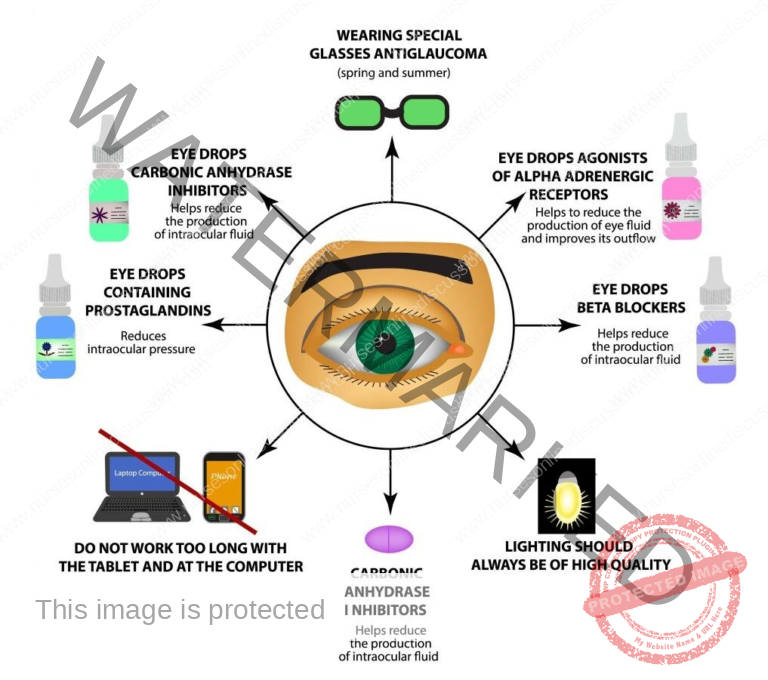

Topical beta blockers: These eye drops reduce the production of aqueous fluid, thereby lowering IOP. Examples include timolol maleate (0.25-0.5% twice daily), betaxolol (0.25-0.5% twice daily), and levobunolol (0.25-0.5% once or twice daily, with a longer duration of action).

Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors: Such as dorzolamide (2%), which lowers IOP by decreasing aqueous fluid production.

Prostaglandin analogs: Like latanoprost (0.005%), which increases the outflow of aqueous fluid.

Miotics: Such as pilocarpine, which constricts the ciliary muscle, opening the trabecular meshwork and increasing aqueous humor outflow.

Adrenergic agonists: Drugs like epinephrine hydrochloride, which decrease aqueous production through vasoconstriction.

Surgical treatment: Considered when medical therapy is insufficient.

Laser therapy: Argon laser trabeculoplasty (ALT) may be performed if the patient doesn’t respond adequately to medication.

Filtering surgery: Trabeculectomy is a surgical procedure that creates a new drainage pathway for fluid to leave the eye.

Drainage tubes: Small tubes can be surgically implanted to drain excess fluid and lower IOP.

Minimally invasive glaucoma surgery (MIGS): These newer procedures offer a lower risk profile and often require less postoperative care compared to traditional surgeries.

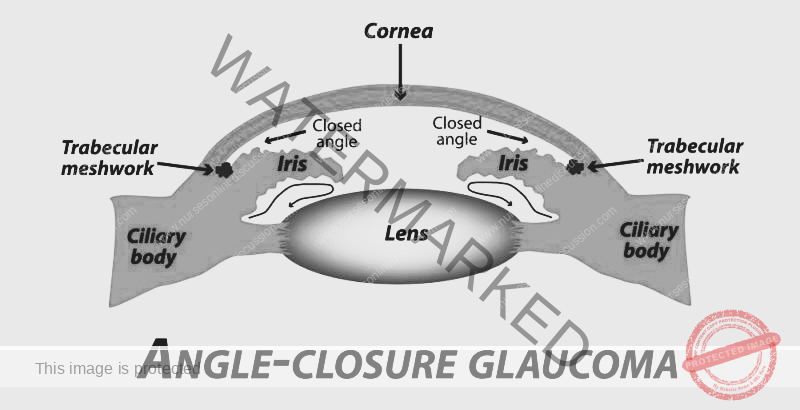

PRIMARY ANGLE CLOSURE GLAUCOMA

Primary angle closure glaucoma, also known as primary closed-angle glaucoma, narrow-angle glaucoma, pupil block glaucoma, or acute congestive glaucoma, is a type of glaucoma characterized by a rapid onset and is considered an ophthalmic emergency. If not treated promptly, it can lead to blindness within a few days.

In this type of glaucoma, the IOP is raised due to the physical narrowing of the anterior chamber angle, obstructing the outflow of aqueous humor. It is more common in females with a predisposed nervous temperament.

Causes and Risk Factors:

Abnormality of the structures in the front of the eyes, leading to a physical blockage of aqueous humor outflow.

Narrow angle anatomy due to factors such as a large lens, a large ciliary body, a small corneal diameter, or a small overall eyeball size.

Anteriorly positioned iris.

Hyperopic eyes (associated with farsightedness).

Precipitating factors:

Dim lighting conditions

Emotional stress or anxiety

Use of mydriatic drugs (which dilate the pupil), such as atropine, tropicamide, and cyclopentolate.

Clinical Features:

The disease course can be divided into subacute and acute congestive glaucoma.

Subacute Glaucoma:

Gradual onset with transient attacks of blurred vision and mild headache.

Temporary increases in intraocular pressure (IOP) during these attacks, lasting from seconds to hours.

Dilated pupils, a shallow anterior chamber, and mild corneal edema may be present during attacks.

Symptoms spontaneously resolve.

Acute Congestive Glaucoma:

Abrupt and significant increase in IOP due to sudden closure of the anterior chamber angle.

Severe eye pain, sudden vision loss, redness of the eye, photophobia (light sensitivity), tearing (lacrimation), nausea, and vomiting.

Dilated pupils that do not react to light and an edematous (swollen) optic disc.

Treatment Options:

The primary goals are to prevent further angle closure and control IOP.

Laser Iridotomy: The standard initial treatment. It eliminates the pupillary block by creating a small hole in the iris, equalizing pressure between the anterior and posterior chambers and widening the angle.

“Stepped-up standard glaucoma medications”: If IOP remains high despite laser iridotomy, additional medications may be necessary. These can include:

Prostaglandin analogs: Like latanoprost, to increase fluid outflow.

Beta blockers: Such as timolol and levobunolol, to reduce fluid production.

Miotics: Like pilocarpine, to constrict the pupil and improve outflow.

Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors: Such as dorzolamide and brinzolamide, to decrease fluid production.

Sympathomimetics: Like dipivefrin, to reduce IOP.

Alpha-2 adrenergic agonists: Such as brimonidine and apraclonidine, to decrease fluid production and increase outflow.

Surgical Options:

Trabeculectomy: Effective for PACG but carries a higher risk of complications like filtration failure, shallow anterior chamber, and malignant glaucoma/aqueous misdirection.

Lens Extraction: Removing the lens, either alone or combined with trabeculectomy, has been shown to deepen the anterior chamber and widen the drainage angle, effectively reducing IOP. Clear lens extraction (CLE) is highly effective in reducing IOP and improving the quality of life for patients with angle-closure glaucoma.

Phacoemulsification: Cataract surgery alone or combined with trabeculectomy may be considered depending on the individual patient’s condition and the presence of a cataract.

CHRONIC CLOSED-ANGLE GLAUCOMA

Chronic closed-angle glaucoma is characterized by a gradual narrowing or intermittent closure of the drainage angle in the eye, leading to a sustained increase in intraocular pressure (IOP) and progressive damage to the optic nerve. If left untreated, this condition eventually progresses to absolute glaucoma, resulting in irreversible blindness.

Treatment Options for Chronic Closed-Angle Glaucoma:

The primary goal of treatment is to lower IOP and prevent further optic nerve damage.

Medical Therapy: Often used as an initial and temporary measure, especially in emergency situations, to rapidly lower IOP before surgical intervention. This may include:

Parenteral analgesics: To relieve severe eye pain.

Intravenous Mannitol: An osmotic diuretic to quickly reduce IOP.

Acetazolamide: A carbonic anhydrase inhibitor, typically given orally (250mg three times a day), to decrease aqueous humor production.

Pilocarpine eye drops (2%): Instilled frequently (e.g., every 30 minutes for 2 hours, then hourly) to constrict the pupil and attempt to open the drainage angle.

Other eye drops: Beta blockers (e.g., Timolol maleate 0.5% twice daily), prostaglandin analogs, alpha agonists, carbonic anhydrase inhibitors, or combinations thereof, to lower IOP.

Corticosteroid eye drops: To reduce inflammation within the eye.

Surgery: The definitive treatment for chronic closed-angle glaucoma.

Laser Iridotomy: Often the first surgical procedure performed. A small hole is created in the iris using a laser to bypass the pupillary block and allow aqueous humor to flow freely, thus reducing IOP.

Trabeculectomy: A more invasive surgical procedure where a new drainage channel is created in the sclera to allow aqueous humor to drain out of the eye, lowering IOP.

Glaucoma Drainage Device Implantation: A small tube, also known as a shunt, is implanted in the eye to facilitate the drainage of excess aqueous humor and reduce IOP.

Cyclophotocoagulation: A laser procedure that targets the ciliary body (where aqueous humor is produced), reducing its ability to produce fluid and thereby lowering IOP.

Absolute Glaucoma

Absolute glaucoma represents the end-stage of all types of glaucoma, characterized by complete and irreversible vision loss or blindness due to chronically elevated intraocular pressure.

In this stage, the eye has no vision, no pupillary light reflex (the pupil doesn’t constrict in response to light), and no pupillary response (the pupil is fixed and dilated). The eye often has a stony-hard feel upon examination. Severe, unrelenting pain is a common symptom. The primary focus of treatment shifts to pain management and ensuring patient comfort.

Risk factors:

Factors that increase the risk of progressing to absolute glaucoma include persistently elevated IOP, fluctuations in IOP, male gender, pseudoexfoliation syndrome, worsening visual field loss, optic disc hemorrhages, migraines, systemic diseases (such as hypertension, diabetes, and myopia), and low socioeconomic status, which can affect access to consistent care.

Causes:

Absolute glaucoma can result from various factors, including uncontrolled elevated IOP over time, poor adherence to glaucoma medication regimens, trauma to the eye, complications from intraocular surgery (particularly cataract extraction), and associations with certain genetic syndromes like aniridia, Lowe syndrome, or Sturge-Weber syndrome.

Symptoms:

In the final stage, patients typically experience severe and constant eye pain, the eye has a hard, stone-like feel, excessive tearing, photophobia, complete absence of the pupillary light reflex, and no pupillary response to light.

In absolute glaucoma, treatment focuses on pain relief:

Retrobulbar injection of alcohol: An injection of alcohol behind the eyeball to deaden the nerves and alleviate pain.

Cryophotocoagulation: A procedure to destroy the ciliary epithelium (the tissue that produces aqueous humor) using extreme cold, thereby reducing IOP and pain.

Enucleation: If conservative pain management approaches are unsuccessful, surgical removal of the painful, blind eye (enucleation) may be necessary to provide relief.

SECONDARY GLAUCOMA

Secondary glaucoma is a form of glaucoma that arises due to existing diseases or conditions within the eye. This distinguishes it from primary glaucoma, which has no identifiable underlying cause.

It can originate from various factors, including uveitis (inflammation of the middle layer of the eye), trauma to the eye, intraocular hemorrhage (bleeding inside the eye), previous eye surgeries, systemic conditions like diabetes, and the prolonged or inappropriate use of steroid medications.

Types of Secondary Glaucoma

Lens-induced glaucoma: This type occurs when the lens of the eye obstructs the trabecular meshwork, which is responsible for draining fluid from the eye. This blockage can be caused by lens proteins or the lens itself swelling, leading to increased intraocular pressure (IOP).

Glaucoma due to uveitis: The inflammation associated with uveitis can directly impact the drainage system of the eye. Inflammatory cells and debris can clog the trabecular meshwork, and the inflammation itself can cause trabeculitis (inflammation of the trabecular meshwork), both of which contribute to elevated pressure within the eye.

Neurovascular glaucoma: This is a more complex and often challenging-to-treat type of glaucoma. It’s frequently triggered by proliferative diabetic retinopathy, where abnormal new blood vessels grow in the retina and iris, obstructing fluid outflow. Individuals with compromised blood flow to the eyes, regardless of the cause, are at greater risk.

Glaucoma associated with intraocular tumors: The presence of tumors inside the eye, such as retinoblastoma (in children) and malignant melanoma (in adults), can physically obstruct the drainage pathways, leading to a rise in IOP.

Steroid-induced glaucoma: Certain individuals are susceptible to developing glaucoma as a side effect of steroid medications, particularly eye drops. These medications can interfere with the drainage system, leading to sudden elevations in IOP. Careful monitoring during steroid use is crucial for prevention.

Pigmentary glaucoma: This is a less common condition where pigment cells from the back surface of the iris detach and disperse into the aqueous humor (the fluid inside the eye). These pigment granules can then clog the trabecular meshwork, resulting in increased IOP.

Treatment of secondary glaucoma is tailored to the specific underlying cause. It often involves a combination of medical management (eye drops), laser therapy to improve drainage, or surgical intervention to create new drainage pathways.

Nursing care for patients with glaucoma

Recognize and assess signs and symptoms of glaucoma. This involves being alert for patient reports and observable indicators of the condition. Monitor intraocular pressure (IOP) using tonometry and evaluate optic nerve function through ophthalmoscopy and visual field testing.

Administer prescribed medications, primarily eye drops, accurately and consistently to effectively manage intraocular pressure.

Educate patients about glaucoma, encompassing risk factors, various treatment options, and the critical importance of regular eye examinations for early detection and monitoring.

Provide support and guidance on strategies to optimize eye health and implement preventive measures to potentially slow disease progression.

Coordinate referrals to ophthalmologists or glaucoma specialists as needed for comprehensive evaluation and ongoing management.

Offer emotional support and counseling to patients as they navigate the adjustment to a glaucoma diagnosis and its potential impact.

Assess for gradual loss of peripheral vision, a hallmark symptom of glaucoma progression. Monitor for increased intraocular pressure as an objective indicator of disease status.

Assess for subjective visual disturbances, including blurred or hazy vision, seeing halos around lights, experiencing vision loss, as well as associated symptoms like headaches or eye strain.

Implement measures to assist patients in managing visual limitations. This includes reducing environmental clutter, strategically arranging furniture to avoid obstacles, and addressing dim lighting and night vision difficulties.

Demonstrate the correct technique for administering eye drops, emphasizing aspects such as counting drops, adhering to the prescribed schedule, and the importance of avoiding missed doses.

Assist with the administration of medications as indicated, including topical miotic drugs (to constrict the pupil and improve drainage) or other specific prescribed medications.

Provide sedation and analgesics as necessary, particularly during acute glaucoma attacks which can be accompanied by sudden and severe pain.

Nursing Diagnosis for Glaucoma

Impaired Visual Sensory Perception related to increased intraocular pressure and optic nerve damage.

Assess the patient’s visual acuity and field to determine the extent of visual impairment. Monitor for changes in visual perception, noting any worsening or new deficits. Provide education on strategies to optimize visual function, such as using assistive devices or adapting the environment.

Risk for Injury related to visual impairment and decreased peripheral vision.

Assess the patient’s mobility and safety awareness to identify potential hazards. Implement measures to reduce environmental hazards, ensuring a safe and accessible environment. Educate the patient on fall prevention strategies, such as using handrails and wearing appropriate footwear.

Anxiety related to the fear of vision loss and the chronic nature of the disease as evidenced by patient asking alot of questions about the diagnosis.

Assess the patient’s anxiety level and coping mechanisms to understand their emotional state. Provide emotional support and counseling to address their fears and concerns. Teach relaxation techniques to help manage anxiety associated with the diagnosis.

Deficient Knowledge related to glaucoma diagnosis and treatment as evidenced by the patient asking alot of questions.

Assess the patient’s understanding of glaucoma to identify knowledge gaps. Provide education on the disease process, treatment options, and the importance of regular eye exams. Encourage the patient to ask questions and clarify any misconceptions they may have.

Noncompliance related to difficulty adhering to medication regimen as evidenced by the patient verbalizing problems in eye drop self administration.

Assess the patient’s understanding of the prescribed medications, including dosage and timing. Identify barriers to medication adherence, such as physical limitations or forgetfulness. Provide education on the importance of medication compliance and strategies to improve adherence, such as using reminder systems.

Disturbed Body Image related to changes in visual appearance and functional limitations as evidenced by the patient wearing black glasses.

Assess the patient’s perception of body image and self-esteem to understand their feelings about their appearance and functional abilities. Provide emotional support and counseling to address body image concerns. Encourage the patient to express feelings and concerns about body image changes in a safe and supportive environment.

Preventive measures for glaucoma

Regular Eye Exams: It’s crucial to schedule routine, thorough eye examinations, particularly if you have factors that increase your risk of developing glaucoma. Early detection through these exams is key to starting treatment and helping to avoid vision loss.

Medication Adherence: If you have been diagnosed with glaucoma or are identified as being at risk, strictly follow the directions provided by your healthcare professional for taking your prescribed medications. These medications play a vital role in lowering the pressure inside your eye and preventing further damage to the nerve responsible for sight.

Know Your Risk Factors: Be informed about the elements that can increase your likelihood of developing glaucoma, including your age, whether glaucoma runs in your family, your race (people of African descent have a higher risk), and the presence of certain medical conditions like diabetes. If you fit into any high-risk category, staying proactive and taking preventive steps is especially important.

Lifestyle Modifications:

Healthy Diet: Focus on consuming a diet abundant in dark leafy greens, brightly colored fruits, berries, and various vegetables. These foods are packed with essential vitamins and minerals that support the health of your eyes.

Regular Exercise: Incorporate regular physical activity at a moderate intensity level. This can contribute to lowering eye pressure and improving your overall health. However, it’s best to avoid very strenuous exercises that cause a significant spike in your heart rate, as these could potentially increase eye pressure.

Eye Protection: Always wear protective eyewear when participating in sports or engaging in activities where there’s a possibility of eye injury. This helps shield your eyes from potential harm.

Avoid Head-down Positions: If you have glaucoma or are considered to be at high risk, try to minimize spending extended periods with your head significantly lower than your body. This is because such positions can cause a noticeable increase in the pressure within your eyes.

Sleep Position: Avoid the habit of sleeping with your eye pressed directly against the pillow or resting on your arm, especially if you suffer from obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). This sleeping position can potentially increase the risk or worsen the severity of glaucoma.

Sun Protection: Use good quality polarized sunglasses and wear a hat to shield your eyes from the damaging effects of ultraviolet (UV) rays from the sun.

Oral Hygiene: Maintain good oral hygiene practices by regularly brushing and flossing your teeth. There is a potential connection between gum disease and damage to the optic nerve in glaucoma.

Blood Pressure Management: Keep your ophthalmologist informed about any medications you take for blood pressure. Low blood pressure, particularly during sleep, can potentially worsen the damage caused by glaucoma.

Complications of glaucoma

Vision Loss: Glaucoma can lead to a gradual and irreversible loss of vision. This typically starts with the outer edges of your vision (peripheral vision) and can eventually progress to affect your central vision.

Blindness: If glaucoma is not treated or is not managed effectively, it can ultimately result in permanent blindness. It stands as one of the primary causes of irreversible blindness around the world.

Optic Nerve Damage: The fundamental problem in glaucoma is damage to the optic nerve. This nerve is critical for transmitting visual information from your eye to your brain, and its damage results in lasting visual impairment.

Increased Intraocular Pressure: Elevated pressure inside the eye can cause discomfort, pain, and headaches. It can also lead to damage to the cornea (the clear front surface of the eye) and changes in the eye’s shape.

Secondary Cataracts: Certain types of glaucoma, specifically angle-closure glaucoma, can trigger the development of secondary cataracts. These are cataracts that form as a consequence of another eye condition.

Macular Edema: In some instances, glaucoma can lead to macular edema. This involves the build-up of fluid in the macula, which is the central part of the retina responsible for sharp, central vision. This fluid accumulation can cause blurred or distorted central vision.

Visual Field Defects: Glaucoma characteristically causes a loss of peripheral vision. This results in the appearance of blind spots in your field of vision and can make activities like driving or navigating through crowded areas difficult.

Corneal Damage: Persistently high pressure inside the eye can cause the cornea to become thinner and damaged. This damage can lead to disturbances in vision and discomfort in the eye.

Emotional and Psychological Impact: Living with glaucoma can have a considerable emotional and psychological impact on individuals. It can lead to feelings of anxiety, depression, and a general decrease in their quality of life.

Related Topics

We are a supportive platform dedicated to empowering student nurses and midwives through quality educational resources, career guidance, and a vibrant community. Join us to connect, learn, and grow in your healthcare journey

Quick Links

Our Courses

Legal / Policies

Get in Touch

(+256) 790 036 252

(+256) 748 324 644

Info@nursesonlinediscussion.com

Kampala ,Uganda

© 2025 Nurses online discussion. All Rights Reserved | Design & Developed by Opensigma