Obstetric Anatomy and Physiology

Female External Genitalia

Table of Contents

OVERVIEW OF ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY OF THE FEMALE REPRODUCTIVE SYSTEM

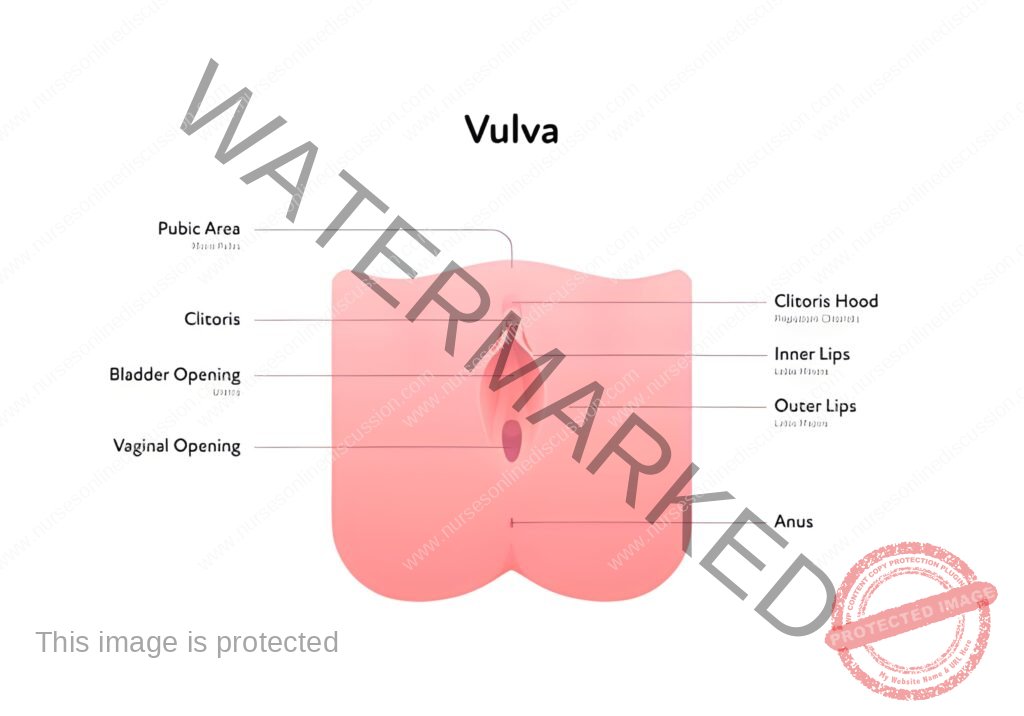

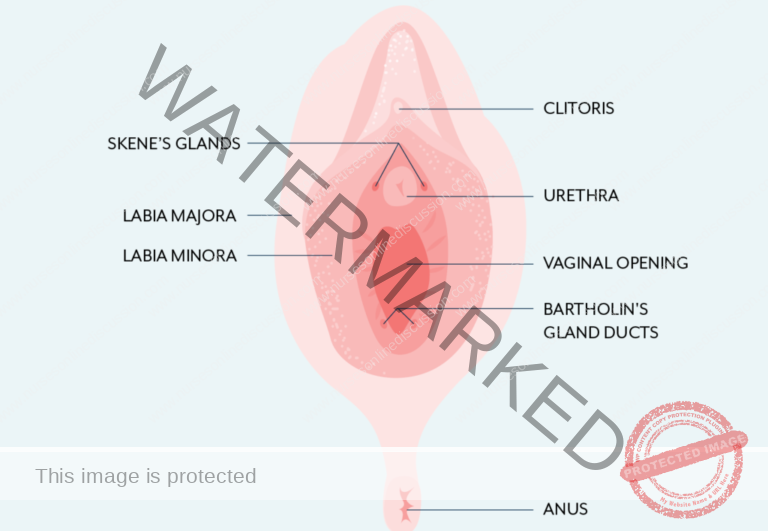

The female external genitalia, collectively known as the vulva, encompasses several structures that are visible externally. These components are: the mons pubis, labia majora, labia minora, clitoris, vestibule, greater vestibular glands (also known as Bartholin’s glands), and the bulbs of the vestibule.

Mons Pubis: This is a fleshy, rounded mound of fatty tissue situated above the pubic bone. After puberty, it becomes covered in pubic hair. Its primary function is to provide cushioning and protection to the pubic bone, particularly during sexual activity.

Labia Majora (‘greater lips’): These are two prominent folds of skin and fatty tissue that extend downwards from the mons pubis, running towards the perineum. They serve as the outer protective folds of the vulva, shielding the more delicate inner structures. Over time, or following childbirth, the labia majora may become less full.

Labia Minora (‘lesser lips’): Located within the labia majora, these are two inner folds of skin that are thinner, smaller, and often more pigmented. They encircle the openings of both the vagina and the urethra. The labia minora are rich in sweat glands, oil glands, and highly sensitive nerve endings. They contain erectile tissue that engorges with blood during sexual arousal, making them very sensitive to touch. At the front, each labium minus splits into two folds: the upper folds merge above the clitoris to create the prepuce, a protective, retractable hood-like covering for the clitoris. The lower folds meet below the clitoris to form the frenulum, a small fold beneath the clitoris.

Clitoris: Positioned at the uppermost part of the vulva, where the labia minora meet, the clitoris is a small, erectile organ that is primarily responsible for sexual pleasure. Partially concealed by the prepuce, it is structurally similar to the penis in males, although smaller and without a role in urination. The clitoris is densely packed with nerve endings, making it exceptionally sensitive to stimulation and the key organ for achieving orgasm in females. The visible part, the glans of the clitoris, is located above the urethral opening and in front of the vagina. Unlike the penis, the clitoris’s sole function is sexual pleasure; it is not involved in the urinary tract.

Vestibule: This is the almond-shaped area enclosed by the labia minora. It is the region that houses the openings to the urethra and the vagina. Essentially, it is the central space within the vulva where the internal reproductive and urinary tracts meet the external environment.

Vaginal Opening (Introitus): Also called the introitus, this is the entrance to the vagina and occupies the posterior two-thirds of the vestibule. In many females, the opening is partially covered by the hymen, a thin membrane. The hymen varies in shape and size and typically tears during initial sexual intercourse or other activities. After tearing, remnants of the hymen remain as small nodules called carunculae myrtiformes, which are named for their resemblance to myrtle berries.

The Urethral Orifice: This is the external opening of the urethra, located approximately 2.5 cm (about an inch) behind the clitoris and just in front of the vaginal opening. On either side of the urethral opening are the ducts of Skene’s glands (paraurethral glands). These are small, short ducts, approximately 0.5 cm long, located within the wall of the urethra.

The Greater Vestibular Glands (Bartholin’s Glands): These are two small glands situated on each side of the vaginal opening, located deeper within the posterior part of the labia majora. They secrete mucus, especially during sexual arousal, which acts as a lubricant for the vaginal opening, facilitating comfortable sexual intercourse. Occasionally, the duct of a Bartholin’s gland can become blocked. If this occurs, the mucus produced by the gland can accumulate, leading to the formation of a Bartholin’s cyst.

Blood Supply: The vulva receives its blood supply from branches of both the internal pudendal arteries and the external pudendal arteries. Venous drainage mirrors the arterial supply, with blood flowing through corresponding veins.

Lymphatic Drainage: The lymphatic vessels of the vulva primarily drain into the inguinal lymph nodes located in the groin region.

Innervation: The nerve supply to the vulva is mainly derived from branches of the pudendal nerve, which provides sensory and motor innervation to the perineum and external genitalia.

Functions of the Vulva:

Protection: The labia majora act as a protective barrier, enclosing and shielding the more delicate internal reproductive organs from physical damage and potential pathogens.

Sexual Arousal: The clitoris, along with the extensive network of sensitive nerve endings in the labia minora, plays a fundamental role in female sexual arousal, sensitivity, and the experience of pleasure.

Reproduction: The vaginal opening is essential for sexual intercourse, allowing for penile penetration and sperm deposition. It also serves as the birth canal through which a baby is delivered during childbirth.

Urination: The urethral orifice, located within the vestibule, provides the external opening for the urinary tract, enabling the elimination of urine from the bladder.

Secretion: The vulva contains numerous glands, including sweat, sebaceous (oil), and vestibular glands, which secrete fluids to keep the area moist, lubricated, and protected.

Childbirth: During vaginal delivery, the tissues of the vulva and the vaginal opening are designed to stretch and expand significantly to allow for the passage of the baby’s head and body.

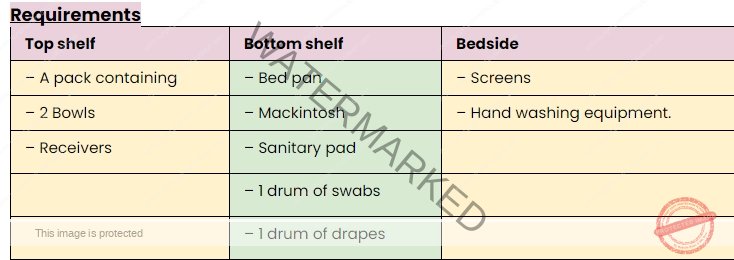

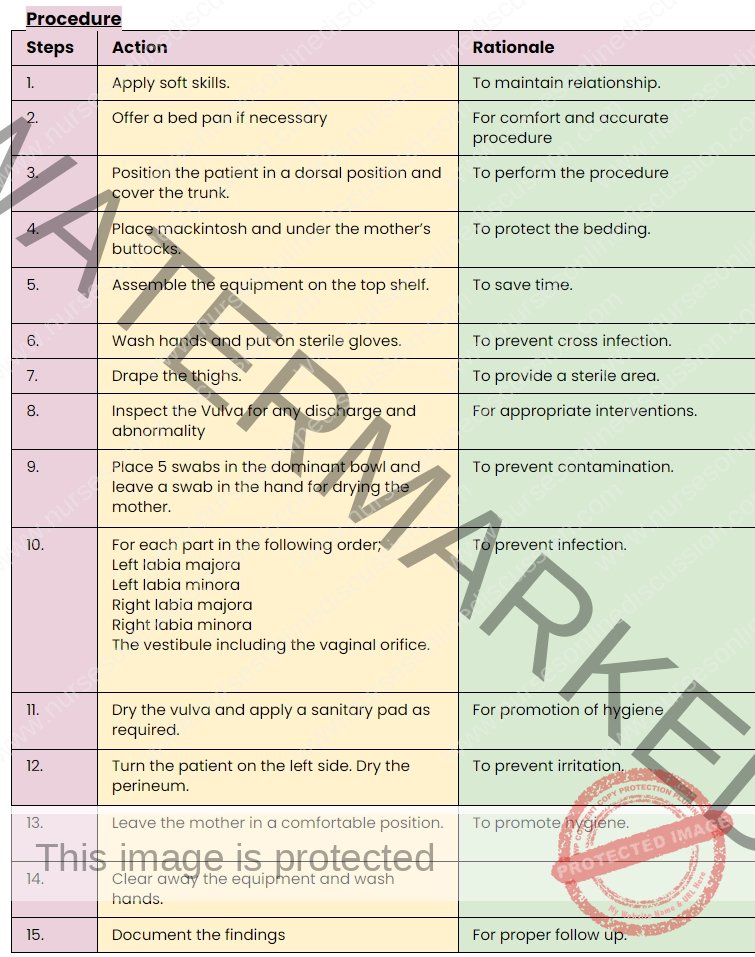

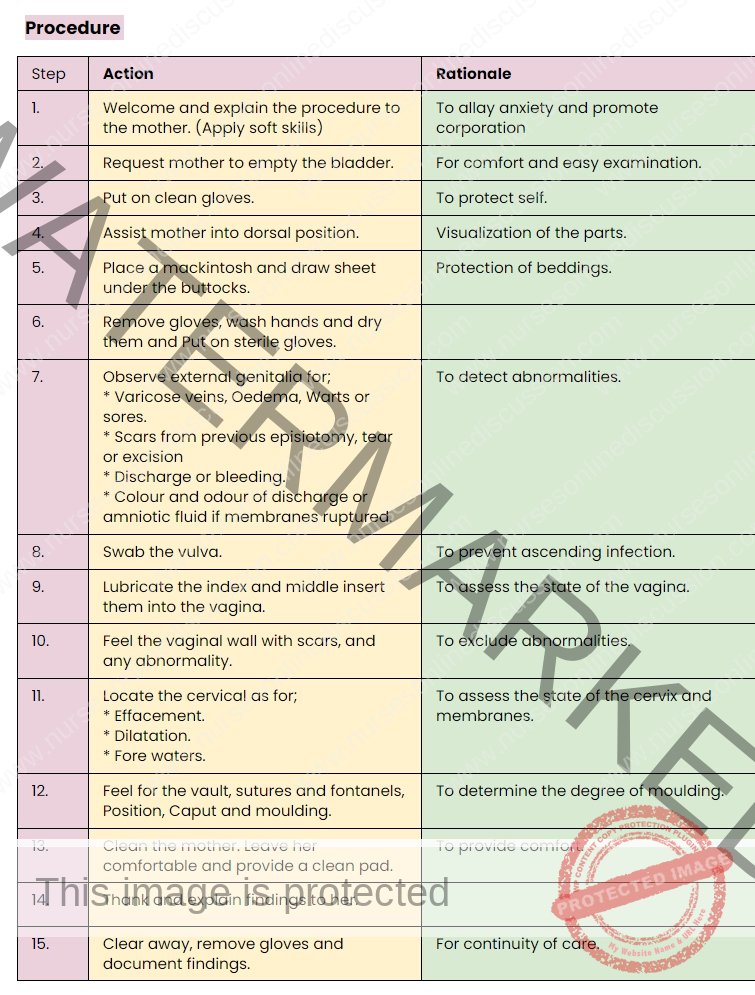

Scenario for Practical

Mother x has come for a postnatal examination. You are required to do vulva swabbing on her.

Task; Perform Vulva Swabbing

Objectives.

1. Set requirements for Vulva swabbing.

2. Perform the Vulva swabbing procedure.

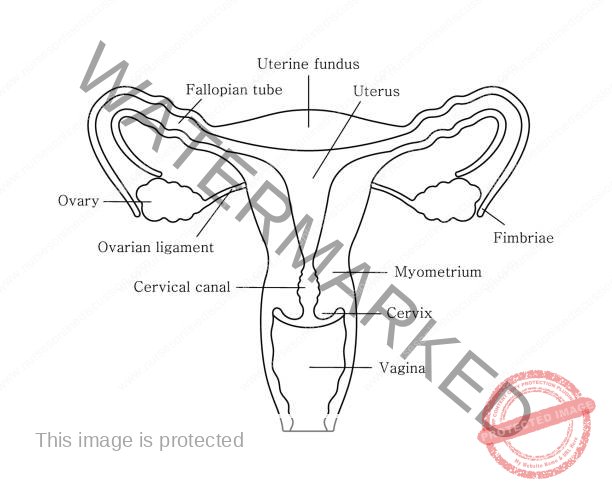

INTERNAL GENITALIA

The internal reproductive system comprises the vagina, cervix, uterus, fallopian tubes, and ovaries, all situated within the pelvic region.

The vagina is a fibro-muscular tube extending from the vulva’s vestibule to the cervix.

The vagina is best described as a fibro-muscular canal, an essential internal organ of the female reproductive system. It stretches upwards and backwards, connecting the external genitalia (specifically the vestibule of the vulva) to the cervix of the uterus. The uppermost, expanded region of the vagina, surrounding the cervix, is known as the vaginal vault.

Typically around 10 centimeters in length, the vagina possesses remarkable elasticity, allowing it to expand significantly during childbirth to accommodate the passage of a baby. The mucous membrane lining the vagina naturally produces secretions that serve to cleanse the vaginal canal and maintain a healthy, slightly acidic environment, which helps to protect against infection. The hymen, a membrane of variable completeness, may partially obstruct the vaginal opening in some individuals. This hymen is typically disrupted during initial penetrative sexual intercourse or other activities.

Shape:

The vagina is described as a potential space or a collapsible tube. Under normal conditions, its walls are in close proximity to each other. However, they are designed to separate and expand, a capacity that is crucial for activities such as sexual intercourse, gynecological examinations, and, most importantly, childbirth.

Size:

There is a slight difference in length between the anterior and posterior walls of the vagina due to the angle at which the uterus joins the vagina. The posterior vaginal wall is longer, measuring approximately 10 cm. The anterior wall is shorter, around 7.5 cm, because the uterus enters the vagina almost at a right angle and then bends forward (anteverted), effectively shortening the anterior wall’s measurable length within the vaginal canal.

Gross Structure:

The vagina is characterized by four recesses or extensions surrounding the cervix, known as fornices (singular: fornix):

Posterior Fornix: This is the deepest of the four fornices, located behind the cervix.

Anterior Fornix: Situated in front of the cervix, this fornix is also relatively deep, though less so than the posterior.

Lateral Fornices (Left and Right): These are located on either side of the cervix, and are shallower in depth compared to the anterior and posterior fornices.

Microscopic Structure of the Vagina (Histology):

The vaginal wall is composed of four distinct layers:

Mucosa: This is the innermost lining. It consists of a stratified squamous non-keratinized epithelium. The epithelial surface is characterized by folds called rugae. These rugae give the vaginal wall its characteristic folded appearance and are critical for the vagina’s ability to stretch and expand significantly when needed, such as during childbirth and intercourse.

Vascular Connective Tissue (Lamina Propria): Beneath the mucosal epithelium is a layer of loose connective tissue that is rich in blood vessels, lymphatic vessels, and nerve fibers. This layer supports the epithelium and provides it with nourishment and sensation.

Muscular Coat (Muscularis): Surrounding the connective tissue is a thin but robust layer of smooth muscle. This muscular layer is composed of both inner circular muscle fibers and outer longitudinal muscle fibers. These muscles contribute to the vagina’s ability to contract and relax, which is important during intercourse and childbirth.

Fascia/Adventitia: This outermost layer is composed of connective tissue, essentially forming a protective outer coat for the vagina. It is continuous with the surrounding pelvic fascia, anchoring the vagina to adjacent pelvic structures and providing structural support.

Contents of the Vagina:

The vaginal cavity itself does not possess any glands that produce secretions. Instead, its moist environment is maintained by several sources. These include mucus from the cervix, fluid that passively filters (transudation) from the rich network of blood vessels situated beneath the vaginal epithelium, and secretions from the Bartholin’s glands located in the vulva. The vaginal environment is naturally acidic, typically with a pH of around 4.5. This acidity is primarily due to the presence of Doderlein’s bacilli, also known as vaginal lactobacilli. These beneficial bacteria convert glycogen, which is present in vaginal epithelial cells, into lactic acid. This production of lactic acid is crucial for maintaining the acidic pH, which serves as a natural defense mechanism, inhibiting the growth of many pathogenic microorganisms and thereby helping to prevent vaginal infections.

Lymphatic Drainage: Lymphatic fluid from the vagina drains into regional lymph nodes, primarily the inguinal lymph nodes located in the groin and the sacral lymph nodes situated in the pelvis near the sacrum.

Nerve Supply:

The vagina receives its nerve supply from branches originating from the pelvic plexus, a network of nerves located in the pelvic cavity. These vaginal nerves generally follow the path of the vaginal arteries, distributing innervation to the vaginal walls and also extending to the erectile tissues of the vulva, contributing to sensation and reflexes in these areas.

Relations to the Vagina (Adjacent Structures):

The vagina is anatomically positioned in close proximity to several other pelvic structures, which are described relative to its orientation:

Laterally: On each side, the vagina is bordered inferiorly (below) by the pubococcygeus muscle, a part of the pelvic floor musculature, and superiorly (above) by the pelvic fascia, a connective tissue layer lining the pelvic cavity.

Inferiorly (Below): The vagina opens externally at the vulva, forming the external vaginal orifice in the vestibule.

Superiorly (Above): The upper end of the vagina is directly connected to the cervix, the lower portion of the uterus that protrudes into the vaginal vault.

Anteriorly (In Front): The front wall of the vagina is related to the urinary system. The upper half of the anterior vaginal wall is adjacent to the base of the bladder, while the lower half is closely associated with the urethra, the tube carrying urine from the bladder.

Posteriorly (Behind): The structures posterior to the vagina vary along its length.

The upper third of the posterior vaginal wall is adjacent to the pouch of Douglas (rectouterine pouch), the deepest part of the peritoneal cavity in the female pelvis, located between the uterus and rectum.

The middle third is positioned in front of the rectum, the final section of the large intestine.

The lower third is related to the perineal body, a central tendinous point in the perineum between the vagina and anus, important for pelvic floor support.

Functions of the Vagina:

The vagina serves multiple critical roles in the female reproductive system:

Menstrual Flow Outflow: It provides the pathway for the discharge of menstrual fluid, consisting of blood, uterine lining, and other secretions, from the uterus during menstruation.

Spermatozoa Entry: It serves as the canal through which spermatozoa (sperm cells) are deposited into the female reproductive tract during sexual intercourse, facilitating fertilization.

Products of Conception Exit: During childbirth, the vagina acts as the birth canal, providing the passage for the fetus, placenta, and fetal membranes to be expelled from the uterus to the external environment.

Uterine Support: The vaginal walls, along with surrounding pelvic floor structures, contribute to the support of the uterus and other pelvic organs, helping to maintain their proper anatomical position within the pelvis.

Prevention of Ascending Infections: The acidic vaginal environment, maintained by lactobacilli, helps to prevent ascending infections by inhibiting the growth and ascent of pathogenic bacteria from the lower reproductive tract into the upper reproductive organs, such as the uterus and fallopian tubes.

Sexual Intercourse Reception: It functions to receive the penis during sexual intercourse, accommodating penile penetration and enabling sexual activity.

Pathway for Fetal Delivery: As the birth canal, the vagina provides the essential pathway for the fetus to pass through during vaginal delivery, allowing for the expulsion of the baby into the world.

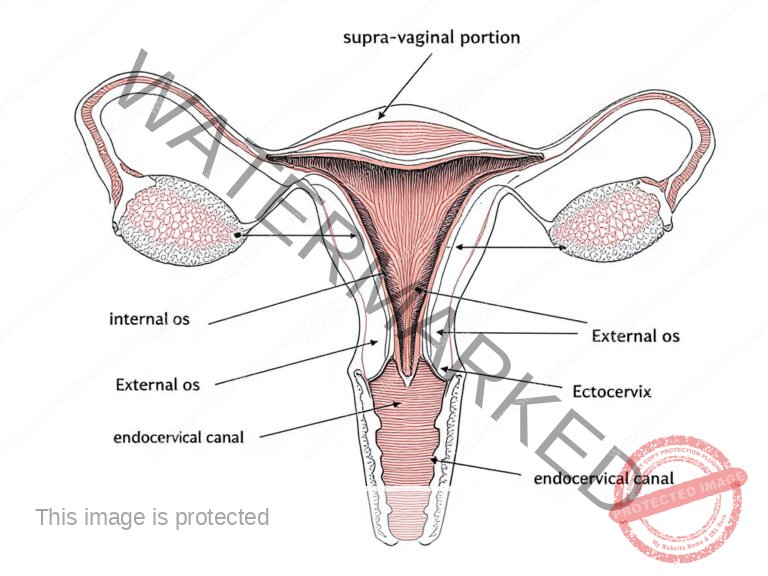

CERVIX

The cervix is the lowermost section of the uterus, projecting into the upper part of the vaginal canal. It acts as a crucial link between the uterus and the vagina, serving as a pathway for menstrual flow, sperm entry, and the passage of a baby during birth.

Comprising the lower third of the uterus, from the isthmus upwards to its connection with the vagina below, the cervix is also commonly referred to as the neck of the uterus due to its shape and position.

The cervix is structurally divided into two primary regions:

Ectocervix: This is the outer portion of the cervix that protrudes into the vagina and is readily visible during a standard gynecological pelvic examination.

Endocervix: This refers to the cervical canal itself, a tunnel-like passage that runs through the cervix, connecting the vaginal canal to the main body of the uterus.

Role in Childbirth: A key function of the cervix is its dramatic transformation during childbirth. As labor progresses, the cervix undergoes significant changes, becoming softer (cervical ripening) and gradually opening (cervical dilation). This dilation is essential to allow the fetus to descend from the uterus and pass through the birth canal. Cervical dilation is a primary indicator that labor has begun and is progressing.

Position (Situation):

The cervix is located within the true pelvis, the lower and more confined part of the pelvic cavity, which houses the reproductive organs.

Shape:

The cervix has a cylindrical shape. The cervical canal, running through its center, is spindle-shaped, meaning it is wider in the middle and narrower at both ends.

Size:

Prior to pregnancy, the cervix typically measures between 2.5 to 3.5 centimeters in length. In women who have had previous pregnancies and deliveries (women with parity), the cervix may be slightly larger, measuring between 3.5 to 4 centimeters.

Gross Structure of the Cervix:

The cervix is structurally composed of distinct regions:

Supra-vaginal Portion: This refers to the section of the cervix situated above its point of attachment to the vagina.

Infra-vaginal Portion: This is the part of the cervix that projects into the vaginal vault. It enters the vagina at approximately a right angle, assuming the uterus is in its typical anteverted and anteflexed position (tilted forward and bent forward).

Internal Os (Endocervix): This is the opening of the cervical canal into the uterine cavity. It marks the junction between the cervix and the body of the uterus, and is also known as the internal opening of the cervix.

Ectocervix (Exocervix): This is the external, outer part of the cervix, which is visible during a gynecological speculum examination. It features the external os, which is the opening of the cervical canal into the vagina, and is also known as the external opening of the cervix.

Endocervical Canal: This is the passageway located between the internal os and the external os, essentially the tunnel running through the cervix. The zone where the endocervix transitions into the ectocervix is known as the transformation zone. This area is clinically significant as it is the most common site for cervical cellular changes, including precancerous and cancerous lesions.

Microscopic Structure of the Cervix:

The cervix is composed of several tissue layers:

Inner Lining (Endometrium): The innermost layer is lined by a specialized type of endometrium unique to the cervix. Instead of a smooth lining, it is characterized by numerous folds or crypts, described as having a tree-like branching pattern, sometimes referred to as arborvitae. These folds are thought to create a complex environment within the cervix that may play a role in modulating sperm transport and preventing backflow into the vagina. Within these crypts are endocervical glands. These glands are lined by columnar epithelium cells that are responsible for producing and secreting cervical mucus. This mucus varies in consistency throughout the menstrual cycle, influencing fertility.

Endometrial Glands: The cervical endometrium is characterized by its distinctive glands, which are composed of several types of cells: sub-columnar basal cells, Rasmus glands (a specific type of cervical gland), mucus-secreting cells (goblet cells), and ciliated columnar cells. It is important to note that unlike the endometrial lining of the main uterine body, the cervical endometrium does not undergo cyclical shedding during menstruation.

Middle Layer (Muscular Tissue): Beneath the inner lining is a layer composed of smooth muscular tissue. These muscle fibers are arranged in both circular and longitudinal orientations. The circularly arranged fibers are particularly important for the dilation of the cervical os (both internal and external openings) during labor, allowing the cervix to open sufficiently for childbirth.

Outer Layer (Peritoneum): The outermost layer is a serous membrane called the peritoneum. It covers only portions of the cervix, specifically the anterior and posterior surfaces. From these points, the peritoneum reflects upwards and over the bladder and other pelvic organs, forming peritoneal folds and pouches in the pelvic cavity.

Blood Supply: The cervix receives its arterial blood supply primarily from the uterine arteries.

Venous Drainage: Venous blood from the cervix is drained by the uterine veins.

Lymphatic Drainage: Lymphatic vessels from the cervix drain into the internal iliac lymph nodes and the sacral lymph nodes in the pelvis.

Nerve Supply: The cervix is innervated by both sympathetic and parasympathetic nerve fibers originating from the Lee-Frankenhauser plexus (also known as the pelvic plexus or uterovaginal plexus).

Supports: The cervix, and by extension the uterus, is supported by several ligaments:

Cardinal Ligaments (Transverse Cervical Ligaments): These strong ligaments extend laterally from the cervix and upper vagina to the lateral walls of the pelvis, providing primary lateral support.

Pubo-cervical Ligaments: These ligaments run anteriorly from the cervix towards the pubic bone, offering anterior support.

Utero-sacral Ligaments: These ligaments extend posteriorly from the cervix and upper vagina, passing backwards to attach to the sacrum. They provide posterior support to the uterus and cervix.

Relations to the Cervix:

Anterior Aspect: Adjacent to the vesicouterine pouch and the urinary bladder.

Posterior Aspect: Situated in front of the rectouterine pouch (also known as the Pouch of Douglas) and the rectum.

Lateral Aspects: Positioned alongside the broad ligament, ureters, and uterine arteries.

Functions of the Cervix:

Barrier against Pathogens: Cervical mucus acts as a natural defense mechanism, hindering the entry of microorganisms into the uterus. During gestation, the cervix is further sealed by a mucus plug, known as the operculum, enhancing this protective function.

Crucial Role in Parturition: During childbirth, the cervix undergoes dilation and retraction. This process is essential to facilitate the passage of the baby and placenta through the birth canal.

Regulation of Sperm Movement: The intricate folds of the cervical mucosa, referred to as the arbor vitae, along with cervical mucus, create a complex environment that helps to prevent sperm backflow after intercourse. These structures may also play a role in sperm selection.

Pathway for Menstruation: The cervix serves as the route for the expulsion of menstrual blood and uterine lining during menstruation.

Sperm Nourishment: Glands within the cervix secrete substances that contribute to the sustenance and viability of spermatozoa.

Facilitation of Sperm Transport: The cervix produces specific mucus that is receptive to sperm during ovulation. This fertile mucus aids in sperm motility and transport towards the uterus.

Revision Questions:

Describe the roles of the arbor vitae within the cervix.

Identify two key physiological functions performed by the cervix.

List four indications for a cervical examination.

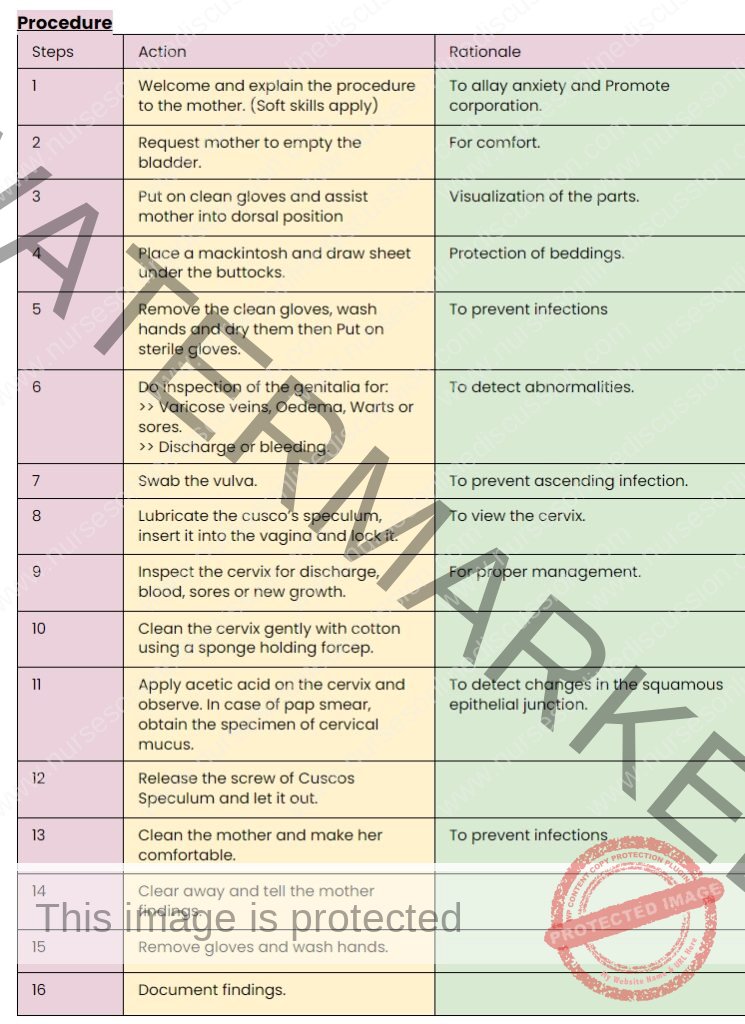

Scenario for Practical Procedure:

Patient Case: A 35-year-old woman, who has given birth previously, presents to a gynecological clinic complaining of painful sexual intercourse (dyspareunia).

Procedure: Acetic Acid Visual Inspection.

Objective: To assess the transformation zone at the squamocolumnar junction for any abnormalities following the application of acetic acid.

Equipment: Standard internal pelvic examination instruments are required, along with a Cusco speculum and sponge-holding forceps, which are particularly necessary for this procedure.

Note.

- If Pap smear is to be done, follow the same steps but obtain a specimen of cervical discharge for examination,

- The epithelium of the cervix undergoes squamous metaplasia at the transformation zone and can form endocervical ectropion and cancer.

Join Our WhatsApp Groups!

Are you a nursing or midwifery student looking for a space to connect, ask questions, share notes, and learn from peers?

Join our WhatsApp discussion groups today!

Join NowGet in Touch

(+256) 790 036 252

(+256) 748 324 644

Info@nursesonlinediscussion.com

Kampala ,Uganda

© 2025 Nurses online discussion. All Rights Reserved Design & Developed by Opensigma.co