Medical Nursing (III)

Subtopic:

Osteoarthritis

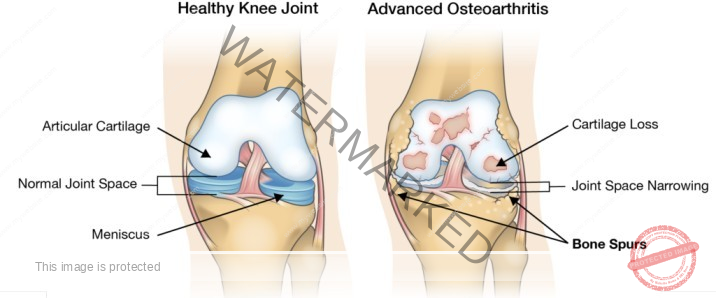

Osteoarthritis is a common form of arthritis that arises when the flexible tissue present at the ends of bones, known as cartilage, deteriorates.

This wearing away of the protective cartilage at the bone ends is a slow and progressive process, meaning it develops gradually and tends to worsen over time.

Consequently, osteoarthritis can also be described as the gradual loss or thinning of the cartilage layer that normally covers the ends of bones within joints, providing a smooth surface for movement.

Osteoarthritis is classified as a degenerative joint disease, indicating that it results from the breakdown of joint tissues. While the term “osteoarthrosis” is sometimes used interchangeably, it’s important to note that inflammation, although not the primary cause, can be present in osteoarthritis.

Osteoarthritis is the most prevalent type of joint disorder and is also a significant cause of disability, impacting mobility and quality of life for many individuals.

Types of Osteoarthritis

Osteoarthritis can be broadly classified into two main categories:

Primary Osteoarthritis:

This is the most frequently encountered type of osteoarthritis. It commonly affects specific joints, including the spine, fingers, hips, knees, and the big toe. Crucially, primary osteoarthritis develops without a clear or identifiable underlying cause. It is often attributed to the natural wear and tear of joints over time.

Secondary Osteoarthritis:

In contrast to the primary form, secondary osteoarthritis arises as a consequence of a pre-existing condition or abnormality affecting the joint. Examples of such predisposing factors include joint injuries or trauma (such as fractures or dislocations), prior episodes of septic arthritis (a bacterial infection within the joint), and congenital abnormalities (conditions present at birth that affect joint structure).

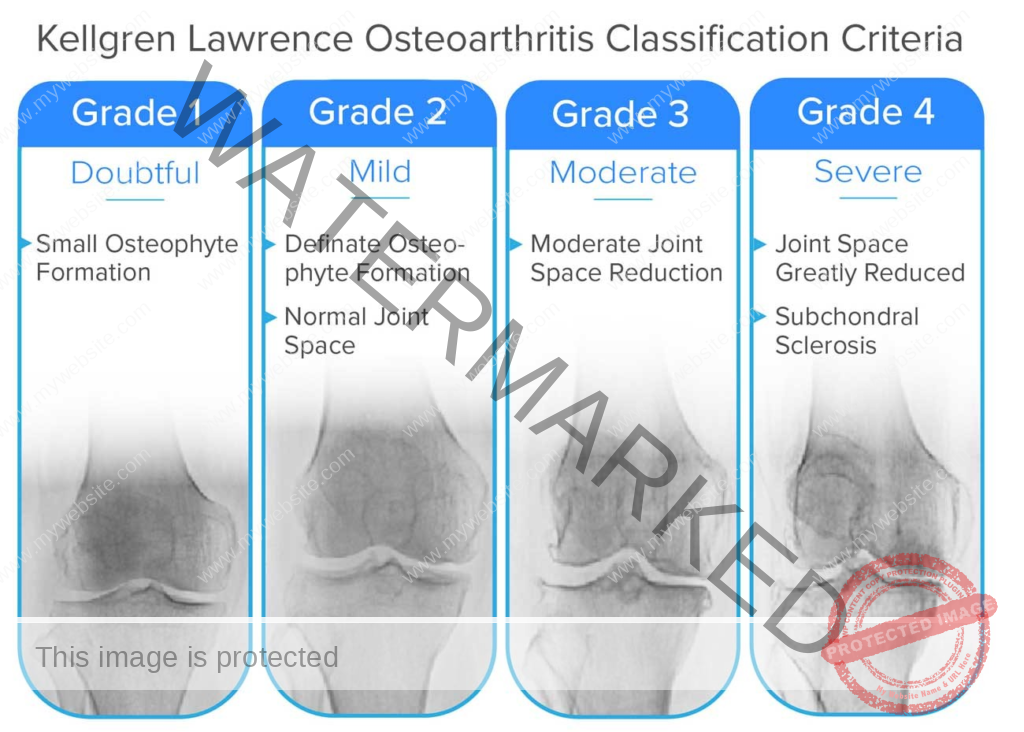

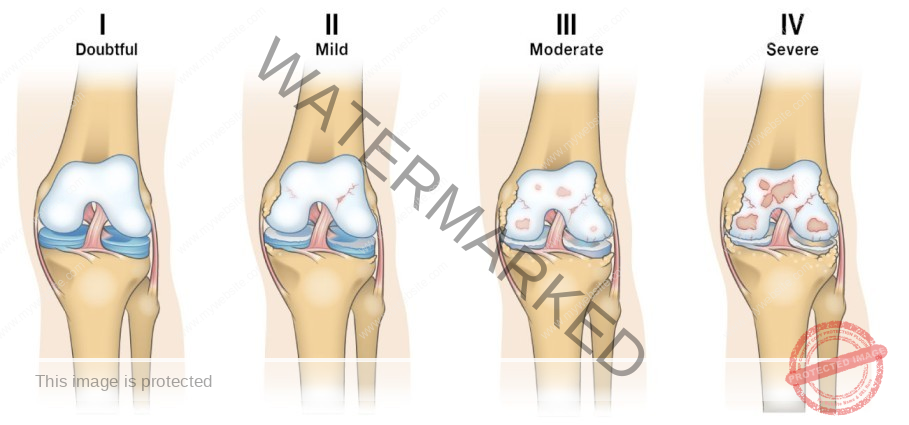

Kellgren-Lawrence Classification of Osteoarthritis

grade 0 (none): definite absence of x-ray changes of osteoarthritis

grade 1 (doubtful): doubtful joint space narrowing and possible osteophytic lipping

grade 2 (mild/minimal): definite osteophytes and possible joint space narrowing

grade 3 (moderate): moderate multiple osteophytes, definite narrowing of joint space and some sclerosis and possible deformity of bone

ends

grade 4 (severe): large osteophytes, marked narrowing of joint space, severe sclerosis and definite deformity of bone ends

Osteoarthritis is deemed present at grade 2 although of minimal severity

Pathophysiology of Osteoarthritis

Osteoarthritis develops when the cartilage, the smooth, protective layer covering the ends of bones within joints, gradually deteriorates or thins. This cartilage normally allows for nearly frictionless joint movement. In osteoarthritis, the smooth surface of the cartilage becomes rough and uneven. Over time, if the cartilage wears away completely, the underlying bones lose their protective covering and begin to rub directly against each other.

The process often begins with a mechanical injury to the joint. This initial injury affects the articular cartilage itself, the subchondral bone (the bone beneath the cartilage), and the synovium (the lining of the joint capsule).

This injury triggers a chondrocyte response. Chondrocytes are cartilage cells. Factors that initiate this response can include previous joint damage, genetic predisposition, hormonal influences, and other individual factors.

Following the chondrocyte response, there is a release of signaling molecules called cytokines. These cytokines contribute to the inflammatory processes within the joint.

The presence of cytokines then leads to the stimulation of enzymes. Key enzymes involved in cartilage breakdown include proteolytic enzymes, metalloproteases, and collagenases. These enzymes are produced and released, actively breaking down the cartilage matrix.

This enzymatic action results in further damage to the cartilage and other joint structures. This damage, in turn, can trigger the chondrocytes to respond again, creating a self-perpetuating cycle of destruction.

Cause

Increased age: The majority of elderly individuals experience some degree of osteoarthritis because, with age, the articular cartilage’s ability to withstand repetitive stress and resist microfractures naturally diminishes.

Obesity: Individuals who are obese place significantly increased stress on their weight-bearing joints (such as hips and knees), leading to accelerated wear and tear of the cartilage.

Previous joint damage: A history of injuries to a joint, such as fractures or ligament tears, can predispose an individual to develop secondary osteoarthritis in that joint later in life.

Repetitive use: Occupations or recreational activities that involve repetitive movements or high-impact stress on specific joints can contribute to the development of osteoarthritis in those joints.

Predisposing Factors

Age: The risk of developing osteoarthritis increases significantly with advancing age, as cartilage naturally degrades over time.

Diabetes or other rheumatic diseases: Certain medical conditions, such as diabetes mellitus and other types of inflammatory arthritis, can increase the risk of developing osteoarthritis.

Genetics: There is a genetic component to osteoarthritis, meaning that individuals with a family history of the condition are at a higher risk.

Hormonal imbalance: Hormonal factors, particularly in women after menopause, may play a role in the development of osteoarthritis.

Bone deformities: Pre-existing structural abnormalities in the bones or joints can lead to uneven stress distribution and increase the risk of osteoarthritis.

Increased cholesterol levels: Some studies suggest a possible link between high cholesterol levels and an increased risk of osteoarthritis.

Obesity: Excess weight puts additional stress on joints, accelerating cartilage breakdown and increasing the risk of osteoarthritis.

Sex: Osteoarthritis is more prevalent in females compared to males, particularly after menopause.

Joint injuries: Past injuries to a joint, even if seemingly minor, can increase the likelihood of developing osteoarthritis in that joint later.

Signs and Symptoms

Limited movements of the joints: A reduction in the normal range of motion in the affected joint is a common symptom as the cartilage deteriorates.

Pain and tenderness: Pain that worsens with activity and tenderness to the touch around the joint are characteristic symptoms of osteoarthritis.

Swelling: The joint may become swollen due to inflammation and fluid buildup within the joint capsule.

Stiffness: Stiffness in the affected joint is often most pronounced after periods of inactivity, such as in the morning or after sitting for a long time. This stiffness typically lasts for a relatively short period.

Crackling noise: A grating or crackling sound (crepitus) may be heard or felt when the joint is moved, resulting from the rough surfaces of the cartilage rubbing together.

Enlarged distorted joints: Over time, the joint may appear enlarged and its normal shape may be distorted due to bone spurs and swelling.

Bone spurs: These are bony outgrowths that can form around the affected joint in response to cartilage damage. They may feel like hard lumps under the skin.

Investigations and Diagnosis

Physical assessment: A thorough physical examination of the musculoskeletal system will reveal tenderness, swelling, and limitations in the range of motion of the affected joints.

X-ray: X-rays are a key diagnostic tool for osteoarthritis. A hallmark finding is the progressive loss of joint cartilage, which appears as a narrowing of the space between the bones within the joint on the X-ray image.

Routine blood tests: While not specific for osteoarthritis, blood tests can be helpful in excluding other conditions, such as infections or inflammatory types of arthritis, that may present with similar symptoms.

MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging): MRI uses radio waves and strong magnetic fields to create detailed images of both bone and soft tissues, including cartilage. This provides a more detailed assessment of cartilage damage and other soft tissue structures within the joint compared to X-rays.

Joint fluid analysis: A procedure called arthrocentesis involves using a needle to draw fluid from the affected joint. Analyzing this fluid can help determine if inflammation is present or if the pain is caused by other conditions such as gout (caused by uric acid crystals) or a joint infection.

Management of Osteoarthritis

Aims

To relieve pain: A primary goal of management is to reduce the pain and discomfort associated with osteoarthritis.

To minimize progress of the condition: While osteoarthritis is a progressive condition, management strategies aim to slow down the rate of cartilage degeneration and joint damage.

To restore normal functions of the bones (joints): The aim is to improve joint mobility, strength, and overall function, enabling individuals to maintain their daily activities.

Management according to classification/ severity

Grade 1 – Doubtful: At this early stage, patients exhibit very minor wear and tear and the development of small bone spurs at the edges of the knee joints. Pain and discomfort are typically rare.

Treatment: If the patient has no other risk factors for osteoarthritis, orthopedic physicians may not recommend specific treatments. Supplements like glucosamine, which may help with cartilage health, might be suggested. Regular exercise is also often recommended to maintain joint mobility and strength.

Grade 2 – Mild: Diagnostic imaging or X-rays of the knee joint will show more noticeable bone spur growth. While the space between the bones still appears relatively normal, individuals may begin to experience symptoms of joint pain. The area around the knee joint may feel stiff and uncomfortable, particularly after prolonged periods of sitting or upon waking up in the morning.

Treatment: Non-pharmacological therapies are the initial focus to relieve pain and discomfort. This includes exercises and strength training to improve joint stability. Assistive devices, such as braces or canes, may also be recommended to reduce stress on the joint.

Grade 3 – Moderate: There is obvious erosion of the cartilage surface between the bones and the appearance of fibrillation (fraying of the cartilage). The space between the bones appears narrowed. A crunching or grating sound (crepitus) may be noticeable during joint movement.

Treatment: Over-the-counter nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or other pain relief therapies are often used. If these are not effective, a doctor may prescribe stronger pain medications like codeine or oxycodone for short-term pain relief. Supportive treatments like physical therapy may be recommended. If conservative measures fail, injections of corticosteroids directly into the joint (articular cortisone) may provide temporary relief. Hyaluronic acid injections, administered over 3-5 weeks, may also be considered to improve joint lubrication.

Grade 4 – Severe: The joint space is significantly reduced, indicating substantial cartilage loss. The remaining cartilage is worn away, leading to bone-on-bone contact within the joint. This results in a chronically inflamed joint with reduced synovial fluid, causing increased friction, greater pain, and significant discomfort during walking or any joint movement. There is increased production of enzymes like synovial metalloproteinases, and inflammatory cytokines such as TNF (Tumour Necrosis Factor), which can further damage the remaining cartilage and surrounding soft tissues.

Treatment: For severe osteoarthritis of the knee, surgical options are often considered. One option is an osteotomy, or bone realignment surgery, where the orthopedic surgeon cuts the bone above or below the knee to shorten or lengthen it, helping to realign the joint and reduce stress. Another common surgical option is total knee replacement, also known as arthroplasty. Arthroplasty involves replacing the damaged joint components with artificial implants.

Prevention

Weight reduction: Maintaining a healthy weight is crucial to reduce the stress placed on weight-bearing joints, thereby slowing the progression of osteoarthritis.

Prevention of injuries: Since previous joint damage is a significant risk factor, taking precautions to avoid injuries to weight-bearing joints is essential. This includes using proper techniques during sports and physical activities and taking steps to prevent falls.

Perinatal screening for congenital hip disease: Early screening and intervention for congenital and developmental disorders of the hip are important, as these conditions are known to predispose individuals to osteoarthritis of the hip later in life.

Keeping a healthy body weight: Maintaining a healthy weight throughout life reduces the burden on joints.

Reduce sugar intake: Some research suggests a link between high sugar intake and inflammation, which can contribute to osteoarthritis.

Complications

Bone death (avascular necrosis): In severe cases, the lack of blood supply to the bone can lead to bone death.

Bleeding inside the joint (hemarthrosis): Damage to the joint can sometimes cause bleeding within the joint space.

Rapid complete breakdown of cartilage: In some instances, the cartilage can deteriorate rapidly.

Infection of the joint (septic arthritis): Although rare, the joint can become infected.

Rupture of tendons and ligaments: The supporting structures around the joint can weaken and rupture over time due to the chronic stress and inflammation.

We are a supportive platform dedicated to empowering student nurses and midwives through quality educational resources, career guidance, and a vibrant community. Join us to connect, learn, and grow in your healthcare journey

Quick Links

Our Courses

Legal / Policies

Get in Touch

(+256) 790 036 252

(+256) 748 324 644

Info@nursesonlinediscussion.com

Kampala ,Uganda

© 2025 Nurses online discussion. All Rights Reserved | Design & Developed by Opensigma