Genitourinary Conditions in Children

Subtopic:

Hydrocele

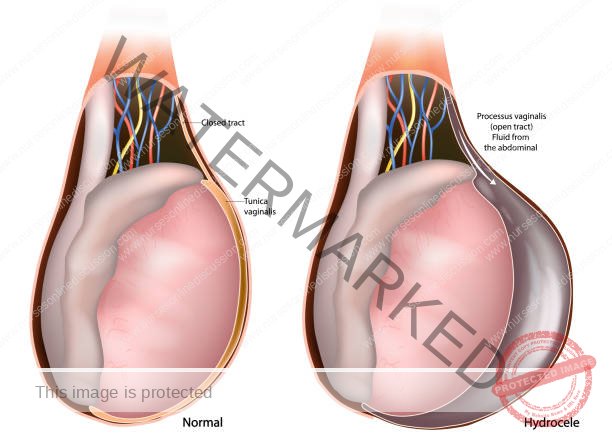

A hydrocele is characterized by a collection of fluid within the tunica vaginalis, a sac surrounding the testicle, or along the spermatic cord. This accumulation of serous fluid within the tunica vaginalis leads to swelling in the inguinal region (groin) or, more commonly, the scrotum.

Hydroceles often manifest as a painless swelling in the scrotum. In infants under one year old, hydroceles typically resolve on their own, as long as there is no accompanying hernia.

In infants, hydroceles are typically caused by the incomplete closure of the processus vaginalis and may or may not be associated with an inguinal hernia. In older boys and men, hydroceles are often idiopathic, meaning the cause is unknown.

Anatomy of the Scrotum

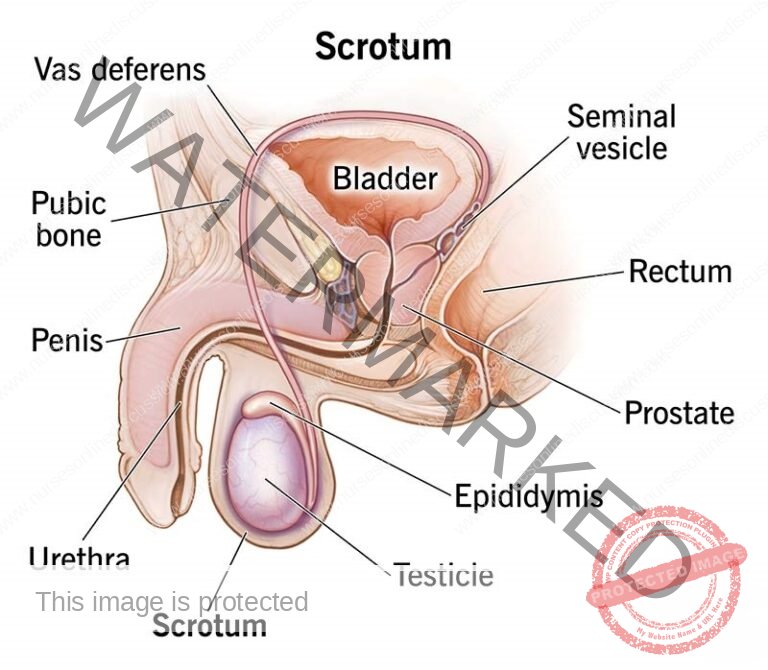

The scrotum is a slender, external pouch of skin divided internally into two sections. Each section houses one of the two testes, the organs responsible for sperm production, and one epididymis, where sperm mature and are stored.

The primary role of the scrotum is to safeguard the testes and maintain them at a temperature slightly lower than the normal internal body temperature. This is why the scrotum extends away from the main body. When the scrotal muscles contract, it helps to retain heat; conversely, when relaxed, the scrotum appears smooth and elongated, allowing air circulation for cooling. This relatively cooler environment is considered crucial for the production of healthy, viable sperm.

Internally, a vertical wall of tissue beneath the skin separates the scrotum into two compartments, each holding a single testis.

Within the subcutaneous tissue lies the dartos muscle, composed of smooth muscle fibers. Contraction of this muscle causes the scrotum to appear wrinkled. When these fibers relax, the scrotum becomes smooth.

The cremaster muscle, made up of skeletal muscle fibers, governs the positioning of the scrotum and testes. In response to cold temperatures or sexual arousal, this muscle contracts, drawing the testes closer to the body for warmth.

Etiology/Causes of a Hydrocele

Hydroceles can arise due to four primary mechanisms:

Excessive Fluid Production: An overproduction of fluid within the tunica vaginalis, the sac surrounding the testicle, such as in cases of acute or chronic epididymo-orchitis (inflammation of the epididymis and testicle).

Impaired Fluid Absorption: A defect in the normal absorption of fluid within the tunica vaginalis, leading to fluid buildup. This can occur with testicular tumors or hematocele (collection of blood in the tunica vaginalis).

Disrupted Lymphatic Drainage: Interference with the normal lymphatic drainage of the scrotal structures. Conditions like elephantiasis or testicular torsion can disrupt this drainage, resulting in hydrocele formation.

Connection with Peritoneal Hernia: In congenital hydroceles, there may be a connection to the peritoneal cavity (the space containing the abdominal organs), leading to a hydrocele of the spermatic cord, as seen with a patent (open) tunica vaginalis.

Risk Factors:

Direct injury or inflammation of the testes

Prematurity

Testicular tumors

Infections of the testicle or epididymitis

Pathophysiology:

During the seventh month of fetal development, the testicles descend from the abdomen into the scrotum. As the testicle descends, a portion of the peritoneum, the lining of the abdominal cavity, wraps around the testicle, forming the tunica vaginalis. This allows fluid from the abdominal cavity to surround the testicle.

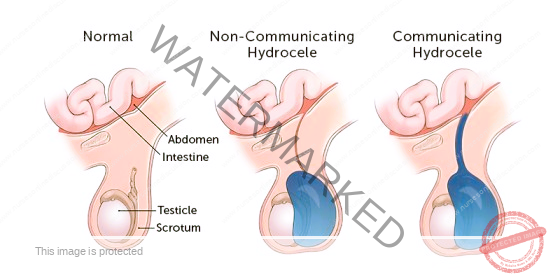

Normally, this sac closes before birth, preventing more fluid from the abdomen from entering the scrotum. The fluid already present is gradually absorbed within the first year of life.

However, if the tunica vaginalis remains open (patent) and connected to the general peritoneal cavity, a communicating hydrocele develops. While this connection exists, it’s usually too small to allow abdominal contents to herniate (protrude) into the scrotum. Applying digital pressure to a communicating hydrocele typically won’t empty it, but the fluid may drain back into the peritoneal cavity when the child is lying down.

Types of Hydrocele

Non-communicating Hydrocele:

In this type, there is no open connection between the abdominal cavity and the tunica vaginalis surrounding the testicle within the scrotum. Non-communicating hydroceles are commonly observed in newborns and often resolve spontaneously over time, sometimes taking up to a year. As long as the swelling is gradually decreasing, it can be safely monitored without intervention.

Communicating Hydrocele:

Here, the tunica vaginalis fails to close properly, leaving an open channel between the scrotum and the abdomen. This allows fluid to flow freely between the two spaces. A characteristic sign of a communicating hydrocele is that the swelling in the scrotum appears smaller in the morning and larger in the evening. This fluctuation is due to changes in abdominal pressure, which cause fluid to move back and forth between the abdomen and the scrotum.

Primary Vs Secondary Hydrocele

Primary Hydrocele

Fluid Reabsorption Defect: Arises from impaired fluid absorption within the scrotum.

Examples: Vaginal and infantile hydroceles exemplify this type.

Size: Can expand to a moderate to large volume.

Testis Palpation: Examination may be difficult to clearly feel the testicle due to fluid accumulation.

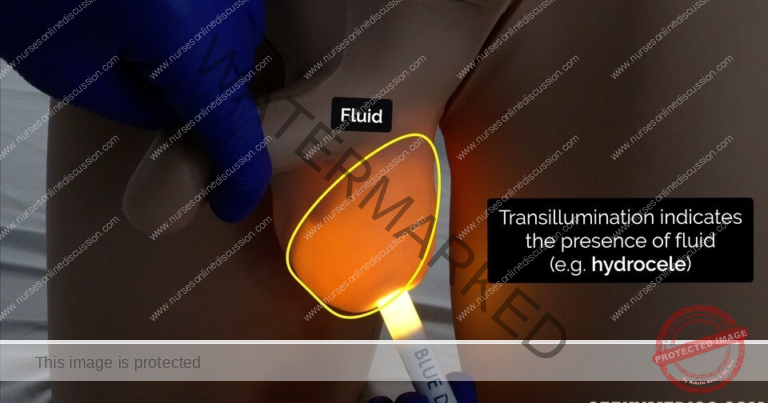

Transillumination: Positive result; light passes through the scrotal swelling when a light source is applied.

Consistency: Characterized by a tensely cystic feel upon palpation, indicating fluid under pressure.

Treatment (Tx): Surgical approaches like Jaboulay’s and Lord’s operations are employed to correct the hydrocele.

Secondary Hydrocele

Excessive Fluid Production: Results from overproduction of fluid within the scrotal sac.

Examples: Conditions such as filariasis, tumors, trauma, and epididymo-orchitis can induce secondary hydroceles.

Size: Typically small in volume.

Testis Palpation: The testicle is usually easily palpable on examination.

Transillumination: Negative result; light does not readily pass through the scrotal swelling.

Consistency: Presents with a lax cystic feel, indicating fluid that is less tense.

Treatment (Tx): Management focuses on treating the underlying cause that is leading to the hydrocele formation.

CLASSIFICATIONS OF HYDROCELES

Primary Hydrocele:

Characterized by a soft, painless swelling in the scrotum.

Typically large in size, often making it challenging to feel the testicle upon physical examination.

Transillumination is a key diagnostic tool, where light will pass through the fluid-filled sac.

Often asymptomatic, but significant size can cause discomfort.

If untreated, prolonged compression or compromised blood flow may potentially lead to testicular atrophy.

Early detection via physical exam may reveal smaller hydroceles where the testis is easily felt within a loose sac.

In cases with a dense hydrocele sac, ultrasound imaging becomes essential to visualize the testis and rule out other testicular issues.

Similar to testicular tumors in being typically painless.

Transillumination serves as a common diagnostic technique: light shines through a hydrocele but is blocked by a solid tumor (except in rare cases of malignancy with a reactive hydrocele).

Subtypes of Hydrocele:

Congenital Hydrocele:

This occurs when the processus vaginalis, a channel connecting the abdomen and scrotum, remains open and continuous with the peritoneal cavity. This allows peritoneal fluid to move into the scrotum, though the opening is typically too small for abdominal organs to herniate through. Applying pressure to the hydrocele usually doesn’t empty it, but the fluid may drain back into the abdomen when the individual lies down. The swelling cannot be felt extending above the inguinal ring, which distinguishes it from a hernia.

Infantile Hydrocele:

In this type, the processus vaginalis closes at the deep inguinal ring, but the portion extending beyond it remains open, allowing fluid to accumulate. While termed “infantile,” this condition can occur in adults as well. Similar to the congenital type, the swelling is confined below the inguinal ring.

Encysted Hydrocele of the Cord:

Here, both the abdominal and scrotal ends of the processus vaginalis close off, trapping fluid within the middle segment. This results in a smooth, oval swelling near the spermatic cord, which can be mistaken for an inguinal hernia. Gently pulling the testis downwards will cause the swelling to move downward and become less mobile.

Vaginal Hydrocele (in females):

In females, a comparable condition called a “hydrocele of the canal of Nuck” can occur. This happens when the canal of Nuck, which is analogous to the processus vaginalis in males, fails to close properly, leading to fluid accumulation and swelling in the groin or labia majora.

Secondary Hydrocele:

A secondary hydrocele develops as a consequence of an underlying condition. These conditions include infections like filariasis, tuberculosis of the epididymis, and syphilis; trauma or injury, such as after hernia repair (post-herniorrhaphy hydrocele); or malignancy. Secondary hydroceles are generally smaller, except those caused by filariasis, which can become very large. Testicular infarction (tissue death), microlithiasis (tiny calcifications) of the testicle, and lithiasis (stones) of the tunica vaginalis can also contribute.

Various testicular diseases, including cancer, trauma (e.g., from a hernia), and orchitis (inflammation of the testis), can lead to secondary hydroceles. They can also occur in infants undergoing peritoneal dialysis. While a hydrocele itself is not cancerous, clinical evaluation is necessary if a testicular tumor is suspected, although there is no established link between hydroceles and testicular cancer in medical literature.

Secondary hydroceles are most commonly associated with acute or chronic epididymo-orchitis but are also seen with testicular torsion and certain testicular tumors. Typically, a secondary hydrocele is soft and moderately sized, and the underlying testis can be felt. The hydrocele usually resolves once the primary condition is treated.

Other predisposing factors for secondary hydroceles include acute or chronic epididymo-orchitis, testicular torsion, testicular tumors, hematocele (blood in the tunica vaginalis), filarial hydrocele (caused by parasitic infection), post-herniorrhaphy, and hydrocele of a herniated sac.

Diagnosis of a hydrocele often begins with recognizing its characteristic clinical presentation.

Clinical Presentation:

Fluctuating Size: The swelling in the scrotum may change in size, typically being smaller in the morning and larger later in the day. This variation is known as a positive fluctuation test.

Discomfort: Patients might experience discomfort due to the feeling of heaviness caused by the scrotal swelling.

Scrotal Swelling: Hydroceles commonly present as a painless swelling on one or both sides of the scrotum.

Transillumination: Shining a focused beam of light through the scrotum will cause it to glow uniformly, without any internal shadows, a finding referred to as positive transillumination.

Impulse on Coughing: Typically, there is no palpable impulse felt when the patient coughs (impulse on coughing negative), although it may be present in congenital hydroceles.

Reducibility: Hydroceles are usually non-reducible, meaning the swelling cannot be easily pushed back into the abdomen.

Palpable Fullness: Examination reveals a soft, non-tender fullness within the scrotum. The testis itself cannot usually be felt separately (testis impalpable) unless it’s a funicular or encysted hydrocele.

Investigations and Diagnostic Findings:

Laboratory Studies: While not specific for hydroceles, laboratory tests may be necessary to rule out other conditions presenting with similar symptoms.

Ultrasonography: This imaging technique provides detailed views of the testicular tissue. It can clearly distinguish hydroceles from spermatoceles (cysts in the epididymis) and can also help identify potential testicular tumors.

Duplex Ultrasonography: This specialized ultrasound assesses blood flow within the testicles, which can be useful if a hydrocele is suspected to be associated with chronic testicular torsion (twisting).

Plain Abdominal Radiography (X-ray): An X-ray of the abdomen may help differentiate an acute hydrocele from an inguinal hernia.

Management and Treatment of Hydroceles

Observation for Infants: Hydroceles that appear in the first year of life often resolve on their own without intervention, requiring only observation and monitoring.

Surgical Removal (Hydrocelectomy): Hydroceles that persist beyond the first year or develop later in life typically require surgical removal through a procedure called a hydrocelectomy. These hydroceles have a low tendency to resolve spontaneously. The preferred surgical method is an open operation performed under general anesthesia for children and either general or spinal anesthesia for adults. Local anesthesia is generally not recommended as it may not adequately manage abdominal pain caused by manipulation of the spermatic cord.

Aspiration Precautions: If a testicular tumor is suspected, aspiration of the hydrocele fluid should not be performed as it could potentially spread malignant cells. Ultrasonography should be used to exclude the presence of a tumor before considering aspiration. If no tumor is identified, needle aspiration of the fluid can be performed.

Post-operative Care: Following surgery, it’s important to provide scrotal support and use ice packs to reduce pain and swelling. Regular changes of surgical dressings, monitoring drainage, and watching for complications are essential to prevent the need for further surgery.

Complications Management: In cases where complications arise (e.g., infection, bleeding), an open operation, potentially including orchiectomy (removal of the testicle), may be necessary depending on the severity.

Jaboulay’s Procedure: After aspirating fluid from a primary hydrocele, it often reaccumulates over time, potentially requiring repeat aspirations or surgery. Surgery is generally preferred for younger patients, while repeated aspirations may be an option for elderly or medically unfit individuals when the hydrocele becomes bothersome. Sclerotherapy, an alternative, involves injecting a solution (e.g., 6% aqueous phenol with 1% lidocaine for pain relief) into the hydrocele sac to prevent fluid reaccumulation. Multiple treatments may be needed.

Aspiration and Sclerosing Agents: While aspirating the hydrocele fluid and injecting sclerosing agents (sometimes with tetracyclines) can be effective, it is often associated with significant pain. These alternative treatments are generally considered less satisfactory due to high recurrence rates and the frequent need for repeated procedures.

Surgical Management:

Surgical management of hydroceles can be approached via several techniques:

Inguinal Approach: This method involves surgically closing off the processus vaginalis high up within the internal inguinal ring. It is the preferred approach for hydroceles in children. If testicular ultrasonography reveals a possible tumor, this approach allows for high ligation and control of the spermatic cord structures.

Scrotal Approach: This involves surgically opening the scrotum and either excising (removing) or everting (turning inside out) and suturing the tunica vaginalis. This approach is typically recommended for chronic non-communicating hydroceles. However, it should be avoided if there’s any suspicion of an underlying malignancy.

Sclerotherapy: This involves aspirating the fluid from the hydrocele and then injecting a sclerosing solution, such as tetracycline or doxycycline, into the scrotum. It is considered an adjunctive or alternative procedure, not a primary one. Recurrence is common after sclerotherapy, and it can also cause significant pain and epididymal obstruction, making it a treatment of last resort for patients who are poor surgical candidates with symptomatic hydroceles and for whom fertility is not a concern.

Hydrocelectomy: This surgical procedure aims to either remove the hydrocele sac entirely or to reshape the remaining tunica vaginalis to facilitate lymphatic drainage through the scrotal lymphatics. This may be considered when other surgical methods have been unsuccessful.

Nursing Interventions

Nursing care for a child with a hydrocele focuses on education, pre- and post-operative care, preventing infection, managing fluid balance and pain, promoting mobility, monitoring for complications, ensuring adequate nutrition, and providing psychosocial support.

Health Education: Provide preoperative education to the child and family. When possible, arrange a visit with operating room staff before surgery. Discuss anticipated sights, sounds, and sensations that might be concerning, such as masks, lights, IV lines, blood pressure cuffs, electrodes, the feeling of oxygen delivery devices, and noises from equipment. Involve the child in age-appropriate discussions about the surgery and encourage them to express their feelings and concerns.

Pre, Intra, and Post-operative Care:

Pre-Operative Care:

Patient Assessment: Conduct a comprehensive assessment, including medical history, current health status, and allergies. Obtain baseline vital signs, laboratory results, and necessary imaging.

Education: Provide information about the surgery, including preoperative instructions, potential risks, and the expected recovery process.

Medication Management: Review current medications and manage them appropriately, including any necessary adjustments before surgery.

Psychological Support: Offer emotional support and address any anxiety or concerns.

Preparing the Surgical Site: Ensure the surgical site is clean and sterile, including hair removal if required.

Intra-Operative Care:

Patient Positioning: Assist in positioning the patient on the operating table for optimal surgical access.

Monitoring: Continuously monitor vital signs (heart rate, blood pressure, oxygen saturation, ECG) and respond promptly to any changes.

Sterile Technique: Help maintain a sterile environment and provide necessary equipment and supplies.

Anesthesia Management: Collaborate with the anesthesiologist to ensure patient comfort and safety during anesthesia.

Communication: Facilitate communication within the surgical team and provide reassurance to the patient.

Post-Operative Care:

Recovery Monitoring: Monitor vital signs, pain levels, and consciousness during recovery from anesthesia.

Pain Management: Administer prescribed pain medication and regularly assess pain levels, providing comfort measures.

Wound Care: Monitor the surgical site for infection or complications and provide appropriate wound care.

Mobilization: Encourage early mobilization and assist with repositioning to prevent complications like deep vein thrombosis and pressure ulcers.

Patient Education: Provide postoperative instructions to the patient and family, including medication management, activity restrictions, and signs of potential complications.

Emotional Support: Offer emotional support and address concerns during recovery.

Reduce Risk for Infection: Confirm that preoperative skin, scrotal, and bowel cleansing procedures (if needed) have been completed. Apply a sterile dressing to prevent contamination. Administer antibiotics as ordered and practice proper hand hygiene and aseptic techniques during care.

Monitor Fluid Volume: Measure and record fluid intake and output, including drainage from tubes. Monitor vital signs, noting changes in blood pressure, heart rate, and respirations. Gradually resume oral intake as appropriate, ensuring adequate hydration.

Relief from Pain: Regularly assess the child’s pain (location, characteristics, intensity on a 0-10 scale). Address anxiety or fear related to the procedure. Identify and address other causes of discomfort. Provide comfort measures like back rubs and heat or cold applications, and use age-appropriate distraction techniques. Administer pain medication as prescribed and evaluate its effectiveness. Encourage the child to communicate their pain and comfort needs.

Promote Mobility: Encourage early mobilization and ambulation as tolerated after surgery to prevent complications like deep vein thrombosis and to promote circulation and respiratory function.

Monitor for Complications: Assess for signs of postoperative complications such as infection, bleeding, or adverse reactions to anesthesia or medications. Monitor the surgical incision site for inflammation, drainage, or other abnormalities.

Encourage Adequate Nutrition: Provide a balanced and nutritious diet to support healing. Offer small, frequent meals if appetite is reduced and encourage fluid intake to prevent dehydration.

Collaborate with the Interdisciplinary Team: Work closely with surgeons, child life specialists, and other healthcare professionals to provide comprehensive care. Communicate any concerns or changes in the child’s condition promptly.

Provide Age-Appropriate Activities: Offer activities and play opportunities suitable for the child’s age to promote emotional well-being and aid in recovery. Provide appropriate entertainment and distraction to alleviate anxiety and boredom during hospitalization.

Get in Touch

(+256) 790 036 252

(+256) 748 324 644

Info@nursesonlinediscussion.com

Kampala ,Uganda

© 2025 Nurses online discussion. All Rights Reserved Design & Developed by Opensigma.co