Psychiatric Emergencies Nursing (II)

Subtopic:

Panic Attacks and Disorders

A panic attack is characterized by a sudden and intense wave of anxiety and fear that feels overwhelming.

Alternatively defined, a panic attack is a sudden episode of extreme fear that triggers significant physical reactions, often occurring without any obvious or immediate danger.

Panic Disorder is diagnosed when an individual experiences recurrent, unexpected panic attacks and spends a considerable amount of time in persistent worry or dread of having another attack.

Causes of Panic Attacks

The exact cause of panic attacks is often unknown (idiopathic), meaning it arises spontaneously without a clear external trigger. However, several factors are believed to contribute to or trigger panic attacks:

Chronic Stress: Prolonged or ongoing stress can lead to the body consistently producing elevated levels of stress hormones, such as adrenaline, potentially making individuals more susceptible to panic.

Acute Stress: Sudden or intense stress, like experiencing a traumatic event, can cause a rapid and overwhelming surge of stress chemicals in the body, triggering a panic attack.

Intense Physical Exertion: For some individuals, vigorous physical exercise may trigger panic attacks due to the body’s physiological response to intense activity being misinterpreted as a threat.

Physical Illness: Underlying medical conditions can induce physical changes within the body that may contribute to panic attacks in susceptible individuals.

Environmental Shifts: A sudden change in surroundings, such as entering a crowded, hot, or poorly ventilated space, can be a trigger for some people, possibly due to sensory overload or feelings of being trapped.

Physical Trauma: Experiences like sexual abuse, particularly in childhood, can have lasting psychological impacts and may predispose individuals to panic attacks.

Genetic Predisposition: Panic disorder appears to have a genetic component, with the condition being observed more frequently among individuals who have family members with panic disorder or other anxiety disorders.

Personality Traits: Certain personality types, such as individuals who are more introverted or prone to anxiety, may be at a higher risk of experiencing panic attacks.

Stimulant Use: Substances that stimulate the nervous system, such as cocaine and certain other drugs, can increase the likelihood of panic attacks due to their effects on neurotransmitter systems.

Biochemical Imbalances: Disturbances in neurotransmitters within the brain are implicated in panic attacks, particularly imbalances in noradrenaline (norepinephrine), serotonin, and GABA (gamma-aminobutyric acid), which play key roles in mood regulation and anxiety response.

Psychological Factors:

Intra-psychic Conflicts: Unresolved internal psychological conflicts may manifest as anxiety and panic.

Conditioned Response/Maladaptive Learning: Panic attacks can develop as a learned or conditioned response to certain situations or sensations, where the body mistakenly associates neutral stimuli with danger.

Recent Life Events: Significant stressful life events, such as failing examinations, job loss, or relationship difficulties, can increase vulnerability to panic attacks.

Hypoglycemia: Low blood sugar levels (hypoglycemia) can trigger physical symptoms that mimic anxiety and may precipitate a panic attack in susceptible individuals.

Medication Withdrawal: Withdrawal from certain medications, particularly sedatives or anti-anxiety drugs, can induce anxiety and panic symptoms.

Mitral Valve Prolapse: This heart condition, where the mitral valve doesn’t close properly, has been linked to increased anxiety and panic attacks in some individuals, although the exact connection is not fully understood.

Hyperthyroidism: An overactive thyroid gland (hyperthyroidism) can cause physical symptoms like rapid heart rate and tremors, which may be misinterpreted as panic or contribute to panic attacks.

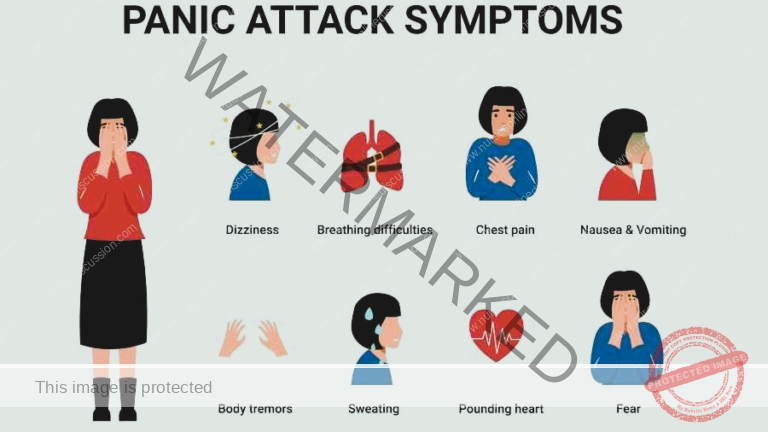

Signs and Symptoms of Panic Attacks

The signs and symptoms of a panic attack typically emerge suddenly and intensely, usually reaching their peak within about 10 minutes.

Most panic attacks are relatively brief, ending within 20 to 30 minutes, and rarely persisting for longer than an hour.

A full panic attack episode often involves a combination of the following physical and psychological signs and symptoms:

Cardiovascular Symptoms:

Heart palpitations (forceful, rapid, or irregular heartbeat).

Chest pain or discomfort.

Accelerated heart rate (tachycardia).

Sensory and Motor Symptoms:

Sweating.

Trembling or shaking.

Tingling or numbness (paresthesia), particularly in the arms and hands.

Feeling lightheaded, unsteady, or dizzy.

Muscle fatigue or weakness.

Tense muscles.

Gastrointestinal Symptoms:

Nausea or stomach upset.

Thermoregulatory Symptoms:

Hot flushes (sudden sensations of intense heat).

Chills or cold flashes.

Dry mouth.

Respiratory Symptoms:

Breathing difficulties, such as shortness of breath (dyspnea) or feeling like you can’t get enough air.

Hyperventilation (rapid and shallow breathing).

A feeling of constriction or tightness in the chest.

Psychological Symptoms:

Anxious and irrational thinking patterns.

A strong sense of dread, impending danger, or foreboding.

Fear of losing control, “going mad,” or dying.

Feelings of unreality (derealization) and detachment from oneself or the environment (depersonalization).

Management of a Panic Attack

Panic attacks are considered a psychiatric emergency that necessitates swift intervention and a coordinated team approach.

Goals of Management

The primary objectives in managing panic attacks and panic disorder are:

(a) Reduce Attack Frequency and Intensity: To lessen how often panic attacks occur and how severe they are when they do happen.

(b) Alleviate Anticipatory Anxiety and Agoraphobic Avoidance: To diminish the constant worry about future attacks and reduce the avoidance of situations or places due to fear of panic.

(c) Treat Co-occurring Psychiatric Conditions: Address any other mental health disorders that may be present alongside panic disorder, as these often complicate the condition and treatment.

(d) Achieve Full Symptomatic Remission: To aim for the complete resolution of panic attack symptoms, allowing the individual to function without the burden of panic.

Practical Management Strategies

Tailored Approach: Treatment strategies should be individualized and depend on the underlying causes and specific presentation of panic attacks in each patient.

Symptom Monitoring: Regularly track the patient’s symptomatic status at each session. This can be achieved through:

Rating Scales: Utilizing standardized scales to quantify the severity of panic symptoms.

Patient Self-Monitoring: Encouraging patients to maintain a daily diary to record and track their panic symptoms, providing valuable insights into patterns and triggers.

Hospital Admission Criteria: For individuals with uncomplicated panic disorder, hospitalization is generally not required unless specific risk factors are present, such as:

Evidence of Dangerous Behavior: Actions indicating harm to self or others.

Drug Withdrawal Symptoms: Complications arising from withdrawal from substances.

Suicidal or Homicidal Ideation: Thoughts or plans of self-harm or harming others, which can occur in the context of severe anxiety or fear.

Suicide Risk Assessment: It is crucial to assess the risk of suicide in all patients presenting with panic disorder, as anxiety disorders can sometimes be associated with suicidal thoughts.

Immediate Symptom Management: For patients presenting with acute symptoms like chest pain, shortness of breath, palpitations, or near fainting (syncope):

Oxygen Administration: Provide supplemental oxygen to address potential hypoxia.

Positioning: Position the patient in a supine (lying flat) or Fowler’s position (semi-seated) to aid breathing and circulation.

Physiological Monitoring: Closely monitor the patient’s physiological parameters using:

Pulse Oximetry: To continuously monitor oxygen saturation levels.

Electrocardiography (ECG): To assess heart rhythm and rule out cardiac causes of chest pain or palpitations.

Patient Education: Educate the patient to understand the nature of their symptoms. Clearly explain that their symptoms:

Are not indicative of a serious medical condition.

Are not due to a psychotic disorder.

Stem from a chemical imbalance related to the body’s “fight or flight” stress response system.

Reassurance and Explanation: Provide frequent reassurance and clear, simple explanations about panic attacks and their management to alleviate fear and misunderstanding.

Social Services Intervention: Involve social services to:

Facilitate supportive discussions with the patient.

Explore resources available for ongoing outpatient care and support in the community.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT): Employ CBT techniques, which are highly effective for panic disorder. CBT helps patients:

Understand Automatic Thoughts: Identify and understand how automatic negative thoughts contribute to anxiety.

Challenge False Beliefs/Distortions: Recognize and challenge unhelpful or distorted beliefs that exacerbate emotional responses like anxiety.

Early Intervention: CBT is often more effective when initiated early in the course of panic disorder.

Behavioral Therapy: Implement behavioral therapy strategies:

Gradual Exposure: Involve a structured approach of sequentially exposing the patient to anxiety-provoking stimuli in a controlled manner.

Desensitization: Over time, through repeated exposure, the patient becomes desensitized to the anxiety-triggering stimuli, reducing their panic response.

Relaxation Techniques: Teach and practice relaxation techniques, such as deep breathing or progressive muscle relaxation, to help patients manage and control anxiety levels.

Respiratory Training: Educate patients on respiratory training techniques. These techniques:

Control Hyperventilation: Help patients gain conscious control over their breathing patterns to prevent or manage hyperventilation, a common symptom during panic attacks.

Anxiety Control: Controlled breathing exercises serve as a tool to self-regulate and reduce overall anxiety levels.

Medication Information: When medication is part of the treatment plan, it is essential to:

Inform about Adverse Reactions: Clearly explain the potential adverse effects or side effects of specific medications being prescribed.

Realistic Expectations: Provide a realistic timeframe for when the patient can expect to see noticeable therapeutic results from medication.

Treatment Duration: Discuss the likely duration of the medication treatment course.

Psychotherapy Approaches

Psychoeducation: Explain to both the patient and their family members that the symptoms are:

Not due to a physical disease: Reassure them that panic attacks are not caused by an underlying medical illness.

Due to a manageable psychological problem: Frame panic disorder as a psychological condition that is effectively treatable.

Reassurance: Reassure the patient that:

Common Condition: Panic disorder is a recognized and relatively common condition, and many individuals experience similar problems.

Time-Limited Episodes: Panic attacks are typically short-lived and episodic, not continuous or permanent states.

Supportive Approach: Be supportive and empathetic towards:

The Patient: Offer understanding, validation, and encouragement.

Family Members: Provide support and education to family members to help them understand and support the patient effectively.

Lifestyle Advice: It is important to advise the patient to reduce or eliminate consumption of:

Alcohol: Alcohol can exacerbate anxiety symptoms and interfere with treatment.

Smoking: Nicotine is a stimulant and can worsen anxiety.

Caffeine: Caffeine, found in coffee, tea, and energy drinks, is a known anxiety-producing agent and should be minimized or avoided.

Nursing Care Strategies

Promote Independence: Nurses should be mindful to avoid fostering patient dependence on nursing staff. Excessive dependence can:

Hinder Therapeutic Progress: Interfere with the development of a healthy therapeutic relationship that promotes patient autonomy and self-management.

Prioritize Comfort and Safety: The nurse’s primary nursing priorities are:

Patient Comfort: Alleviating distress and promoting physical and emotional comfort.

Patient Safety: Ensuring a safe environment and preventing harm to the patient.

Approach to Anxious Patients: When dealing with patients exhibiting heightened anxiety symptoms such as tension, trembling, or sweating:

Calm and Quiet Environment: Approach the patient in a calm and quiet manner and in a setting that minimizes stimulation.

Gentle Handling: Use a gentle and non-threatening approach to de-escalate anxiety.

Reality Acceptance: The nurse should guide and educate the patient to accept the reality of their condition and the need for treatment.

Exposure Therapy Support: Support and facilitate exposure therapy by:

Encouragement: Encourage the patient to return to or remain in situations or places that trigger anxiety, as part of the gradual desensitization process.

Drug Treatment Options

Anxiolytic Medications: Medications to reduce anxiety are a core component of treatment.

Long-Term Management Education: Educate the patient about the importance of long-term management, emphasizing:

Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs): As first-line medications for long-term panic disorder management.

Psychotherapeutic Techniques: The role and benefits of ongoing psychotherapy, particularly CBT, in conjunction with medication.

Benzodiazepines: These medications offer rapid relief from anxiety symptoms but have specific considerations:

Not for Long-Term Monotherapy: Benzodiazepines are not recommended for long-term, stand-alone treatment of panic disorder due to dependence potential.

Reserved for Refractory Cases: They are typically reserved for patients with severe or refractory panic disorder who have not responded adequately to other treatments.

Short-Term Use and Combination Therapy: Can be used for short-term symptom control or in combination with SSRIs during the initial phase of SSRI treatment (as SSRIs take several weeks to become fully effective).

Clonazepam Preference: Clonazepam is often preferred over alprazolam due to its longer half-life, which reduces the risk of rebound anxiety and withdrawal symptoms compared to shorter-acting alprazolam, which has a higher abuse and dependence liability.

Examples of Benzodiazepines and Dosages:

Lorazepam: 1-2 mg every 4 hours as needed for acute anxiety.

Diazepam: 10-20 mg intravenously for acute, severe panic (though less commonly used for panic disorder long-term).

Clonazepam: 0.5-2mg once daily, often used for longer-term management when benzodiazepines are indicated.

Antidepressant Medications: Certain antidepressants are effective in treating panic disorder.

Tricyclic Antidepressants (TCAs): e.g.,

Amitriptyline: Starting dose of 25mg at night (nocte), gradually increasing to 50mg once daily.

Imipramine: Starting dose of 25mg at night (nocte).

Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs): Considered first-line antidepressants for panic disorder due to better side effect profiles than TCAs. e.g.,

Fluoxetine: Initial dose of 10 mg once daily (stat), with a maintenance dose of up to 60 mg daily.

Sertraline: Starting dose of 50mg once daily, with a maintenance dose up to 200mg once daily.

Get in Touch

(+256) 790 036 252

(+256) 748 324 644

Info@nursesonlinediscussion.com

Kampala ,Uganda

© 2025 Nurses online discussion. All Rights Reserved Design & Developed by Opensigma.co