Common Conditions in Palliative Care

Subtopic:

Bereavement, Mourning & Grief

Bereavement

Bereavement describes the state of experiencing a loss. This term broadly refers to the condition of having been deprived of something or someone valued.

The experience of bereavement is profoundly personal and unique to each individual. The grieving process is shaped by a multitude of factors, including:

Personality and Coping Style: Individual personality traits and typical coping mechanisms significantly influence how grief is experienced and managed.

Life Experiences: Past experiences, particularly previous encounters with loss, can shape an individual’s current grieving process.

Faith and Belief Systems: Religious and spiritual beliefs often provide a framework for understanding loss and offer comfort and support during bereavement.

Nature of the Loss: The specific circumstances and significance of the loss itself play a crucial role in the grieving process.

It is important to acknowledge that the grieving process is not linear and unfolds over time. There is no set timeline for grief, and individuals may experience a wide range of emotions and responses throughout their bereavement journey.

Grief

Grief is defined as a complex process encompassing emotional, cognitive, functional, and behavioral responses triggered by loss or death.

More specifically, grief is the emotional and psychological experience that is activated when something deeply valued or cherished is lost. This could be tangible, like a possession, or intangible, like a relationship or a loved one.

Grief is a natural and universal human response to loss. It represents the emotional suffering and distress felt when something or someone significant is taken away. Grief can be experienced by:

Individuals: The personal and subjective experience of loss.

Families: The collective emotional impact of loss on a family unit.

Communities: The shared grief felt by a community in response to a significant loss affecting the collective.

Grief is often experienced most intensely following the death of a loved one (as highlighted by HAU, 2011), but can also be triggered by other significant losses, such as the end of a relationship, loss of health, or loss of a significant aspect of one’s life.

Mourning

Mourning represents the period of time required to navigate the grieving process. It is the outward expression of grief, often influenced by cultural, social, and personal factors.

The duration of mourning is highly variable and depends on a range of factors:

Manner of Death: The circumstances surrounding the death significantly impact the mourning period:

Prolonged Illness: Death following a long illness may allow for anticipatory grief and a potentially different mourning trajectory.

Sudden Death: Unexpected deaths can lead to more intense and prolonged grief reactions.

Traumatic Death: Traumatic deaths, such as those resulting from car accidents, violence, or medical errors, can be particularly challenging to process and mourn.

Age of the Deceased: The age of the person who has died influences the grieving process:

Child’s Death: The death of a child is often perceived as particularly tragic and “out of order,” leading to intense grief and a potentially longer mourning period.

Older Person’s Death: The death of an older person, particularly after a long life, may be grieved differently, often involving reflection on a longer history of relationships and experiences.

Age of the Bereaved: The bereaved individual’s age and developmental stage play a role in their response to loss:

Child Development: A child’s developmental stage influences their understanding and expression of grief.

Life Stage: The bereaved person’s current life stage (e.g., young adulthood, midlife, older age) affects their perspective on loss and available coping resources.

Gender: Societal expectations and gender roles can influence the expression of grief:

Emotional Expression: Women are often culturally allowed or expected to express emotions more openly than men, potentially shaping how mourning is outwardly manifested and perceived.

Previous Experiences of Loss: Prior experiences with loss and how those experiences were processed and coped with can significantly impact an individual’s current grieving process. Cumulative grief can be more challenging.

Support Systems: The availability and quality of social support systems are crucial in navigating grief. Strong social networks can provide emotional, practical, and social support during mourning.

Personal Coping Styles: Individual coping mechanisms and resilience factors influence how grief is managed. Some individuals may be more naturally resilient or possess more adaptive coping strategies.

Family and Culture: Family dynamics and cultural norms significantly shape mourning practices, rituals, and expected behaviors during bereavement. Cultural traditions often provide structure and support for grieving individuals and communities.

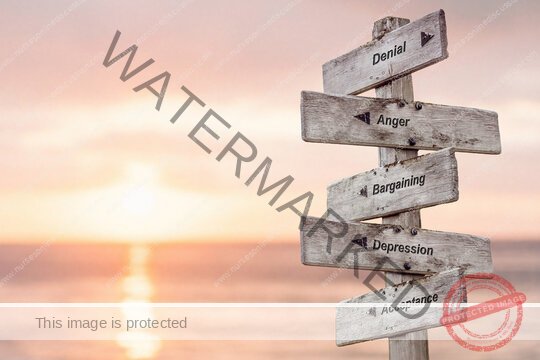

Stages of Grief/Grieving

Experiences of grief can often be understood as progressing through a series of stages, although it is important to remember that these stages are not always linear or experienced in a specific order. Individuals may skip stages, revisit stages, or experience them in a different sequence. These stages are:

Stage One: Denial – Disbelief and Initial Refusal

Initial Reaction: Characterized by a refusal to accept the reality of the loss or its implications, often expressed as: “This can’t be happening to me,” or “The diagnosis must be incorrect.”

Description: In this initial stage, individuals struggle to process the shock of the loss. It acts as a buffer against overwhelming emotions.

Common Coping Mechanisms in Denial: Individuals may engage in:

Magical Thinking: Holding onto beliefs that the loss can be undone or reversed through supernatural or unrealistic means.

Regression: Adopting childlike behaviors, seeking comfort and reassurance from others as a way to avoid confronting the reality of the situation.

Withdrawal: Isolating oneself emotionally and socially, believing that avoidance can shield them from the pain of loss.

Rejection of Truth: Actively refusing to accept the reality of the loss, clinging to the hope that it is not true.

Stage Two: Anger – Questioning and Blame

Emotional Outburst: Marked by intense feelings of anger and resentment, often expressed through questions like: “Why is this happening to me?” or “It’s unfair!”

Description: As denial begins to subside, anger emerges as a powerful emotion. It can be directed at various targets, reflecting the individual’s struggle to make sense of the loss and injustice they feel.

Common Coping Mechanisms in Anger: Individuals may:

Self-Blaming: Direct anger inward, inappropriately blaming oneself for the loss or trauma.

Switching Blame: Shift blame to external targets, such as medical professionals, fate, or other individuals perceived as responsible.

Aggressive Anger: Express rage and anger aggressively, believing they are entitled to lash out due to their pain.

Importance of Expression: Anger, while painful, is a natural part of grief and needs healthy expression. Suppressing anger can lead to emotional blockage and potentially contribute to depression, hindering the grieving process.

Stage Three: Bargaining – Attempting to Negotiate

Seeking Control: Characterized by attempts to negotiate or make deals to postpone or undo the loss, often using phrases like: “If only…” or “I promise to…”

Description: In this stage, individuals try to regain a sense of control in the face of powerlessness. They may seek to bargain with a higher power or others to alleviate their pain or reverse the loss.

Common Coping Mechanisms in Bargaining: Individuals may:

Shop Around: Seek alternative solutions or “miracle cures,” hoping to find a way to undo the loss or pain.

Take Risks: Engage in risky behaviors or make desperate attempts, believing they can somehow influence the outcome or find an answer to their pain.

Take More Care for Others: Focus excessively on the needs of others, sometimes to the point of neglecting their own emotional needs and pain.

Loss of Confidence: Bargaining often reflects a lack of confidence in one’s own ability to cope with the pain directly, leading to seeking external solutions or interventions.

Stage Four: Depression – Overwhelmed by Loss

Confronting Reality: A stage of profound sadness and despair, characterized by the realization of the loss’s full impact, often expressed as: “This is my reality,” or “There’s no point in fighting anymore.”

Description: As bargaining fails to alter the reality of loss, individuals may experience a deep sense of depression. This stage involves confronting the pain, hurt, and overwhelming emotions associated with loss.

Common Experiences in Depression: Individuals may:

Experience uncontrollable crying spells, sobbing, and weeping, reflecting deep sorrow.

Withdraw into silence, becoming morose, deeply thoughtful, and melancholic.

Feelings of:

Guilt: Believing they are somehow responsible for the loss, even if irrationally.

Loss of Hope: Feeling a profound lack of hope for the future, doubting the possibility of regaining order or calm in life.

Loss of Faith: Questioning or losing trust in previously held beliefs or faith systems due to the experience of loss.

Stage Five: Acceptance – Peaceful Adjustment

Coming to Terms: A stage of resignation and peaceful acceptance of the loss as an irreversible part of life, often marked by the realization: “This is now my new reality, and I must adapt.”

Description: Acceptance is not necessarily happiness, but a state of understanding and peaceful resignation to the reality of the loss. It signifies a shift towards adjusting to life after loss.

Characteristics of Acceptance: Individuals in this stage are able to:

Describe the Terms and Conditions of Loss: Articulate and understand the specific nature and circumstances of their loss with clarity and composure.

Cope with Loss: Develop and utilize effective coping mechanisms to manage the ongoing challenges and emotional impact of the loss.

Handle Loss-Related Information Appropriately: Process and manage information related to the loss in a more balanced and adaptive manner.

Adaptive Behaviors in Acceptance: Individuals may engage in:

Adaptive Behavior: Actively adjusting their lives and routines to accommodate the changes brought about by the loss and moving forward.

Appropriate Emotion: Freely express and verbalize their emotional responses to the loss, demonstrating a healthier processing of pain, hurt, and suffering.

Patience and Self-Understanding: Develop patience with themselves and set realistic expectations for the time needed to adjust to their changed life and learn to cope effectively with the loss.

Types of Grief

Normal/Uncomplicated Grief:

Characterized by the ability to move through the stages of grief in a healthy way.

Individuals experiencing normal grief are able to progress towards resolution of their loss over time.

Anticipatory Grief:

This type of grief occurs before an expected loss actually happens.

It is experienced in anticipation of a future loss, such as when someone is facing a terminal illness of a loved one.

Maladaptive Grief:

Describes grief where an individual struggles to progress through the typical stages of grieving and achieve resolution.

Maladaptive grief encompasses several subtypes, indicating different ways the grieving process can become complicated or prolonged:

Delayed Grief:

Grief that is not experienced immediately after a loss.

The emotional response is postponed and may emerge later, sometimes unexpectedly.

Inhibited Grief:

Experienced by individuals who find it very difficult to express their emotions openly.

Commonly observed in individuals who are naturally reserved or in certain demographics like children, who may lack the emotional vocabulary or societal permission to express grief directly.

Chronic Grief/Prolonged Grief:

A situation where the effects of loss persist for an extended duration.

The grieving individual continues to feel the impact of the loss long after typical grieving periods.

May manifest in unusual or abnormal behaviors, such as:

Frequent visits to the deceased’s grave, beyond culturally normative periods.

Persistent low self-esteem and negative self-perception.

Excessive crying or distress upon hearing of any death, even unrelated ones.

Preoccupation with the deceased, constantly talking about or focusing on the lost person.

Loss of libido or decreased sexual interest.

Unexplained physical aches and pains without medical cause.

Disenfranchised Grief:

Grief that is not socially recognized or validated.

Occurs when a loss is not openly acknowledged, mourned publicly, or socially supported.

Can happen when the relationship is not socially sanctioned, or the loss is not considered significant by society.

An example is experiencing grief when a loved one with dementia undergoes significant cognitive decline, representing a loss of their former self even while physically present.

Cumulative Grief:

Arises when an individual experiences multiple losses in a relatively short timeframe.

Can be particularly overwhelming and stressful as there is insufficient time to adequately grieve one loss before another occurs.

Masked Grief:

Grief that is expressed indirectly, often converted into physical symptoms or negative behaviors.

The individual experiencing masked grief may be unaware that these symptoms or behavior changes are connected to their underlying grief.

The grief response is not consciously recognized as such.

Distorted Grief:

Characterized by extreme or disproportionate emotional reactions.

May present with intense guilt or overwhelming anger that are beyond typical grief responses.

Noticeable changes in behavior that are significantly outside the person’s usual character.

Hostility directed towards specific individuals, often unrelated to the loss itself.

Engaging in self-destructive behaviors as a maladaptive way of coping with grief.

Exaggerated Grief:

Represents an intensification of the normal stages of grief over time.

Instead of lessening, the intensity of grief reactions increases or becomes more pronounced as time passes.

Factors That Can Make Grief More Challenging, Harder, and Prolonged

Relationship with the Deceased:

Close and Positive Relationships: Grief can be more intense and prolonged when the bereaved individual had a very close, loving, and positive relationship with the deceased. The deeper the bond, the harder it may be to adjust to the loss.

Difficult or Distant Relationships: Paradoxically, complex or unresolved relationships, even distant ones, can also complicate grief, though the manifestation may differ.

Circumstances of Death:

Natural Causes: Grief following death from natural causes, especially after a long illness, may be different from that following sudden or traumatic death.

Accident, Suicide, or Homicide: Deaths due to accidents, suicide, or homicide are often associated with more complex and prolonged grief due to the suddenness, trauma, or feelings of guilt and anger involved.

Location of Death: Whether death occurs at home, in a hospital, or far from home can impact the grieving experience and access to support.

Personal History:

Past Loss Experiences: Individuals with a history of unresolved grief or early life losses, such as the death of a parent during childhood, may find current grief experiences more challenging to navigate.

Individual Personality and Beliefs:

Unique Coping Styles: Personal coping mechanisms, resilience levels, and emotional processing styles vary greatly and influence how grief is experienced and managed.

Belief Systems: Religious, spiritual, and philosophical beliefs shape how individuals find meaning in loss, cope with suffering, and view death and the afterlife, affecting the grieving process.

Social Factors:

Social Stigma and Lack of Acknowledgement: Grief can be significantly complicated when the loss is socially stigmatized or not openly acknowledged, such as grief related to deaths from AIDS or suicide, or losses within marginalized communities.

Lack of Social Support: Insufficient social support networks, isolation, or lack of understanding from others can make the grieving process much more difficult and isolating.

Unacknowledged Grief:

Marginalized Groups: Grief experienced by certain groups, such as LGBTQ+ individuals, or children, may be less readily acknowledged or validated by broader society, leading to disenfranchised grief and added challenges in mourning.

Lack of societal validation and recognition of the legitimacy of their grief can further complicate the grieving process for these individuals.

Grief Counseling

Grief counseling and bereavement support are essential in providing aid to individuals and families as they navigate the challenging experience of loss. Counselors utilize specific principles and approaches to offer compassionate care and facilitate healing during bereavement.

Principles of Effective Grief Counseling

Expressive Support and Empathy: Show genuine compassion and understanding towards the grieving person. Create a secure and non-judgmental environment where they feel safe to freely express their emotions without fear of judgment.

Validation of Loss: Recognize and affirm the significance and validity of the individual’s loss. Foster an atmosphere of acceptance where the person feels genuinely heard and their experience is acknowledged as real and important.

Acceptance of Grief’s Uncontrollability: Help individuals understand that grief is a natural, unpredictable process. Emphasize that there is no way to control or rush the grieving timeline, and that it unfolds at its own pace.

Normalization of Feelings and Reactions: Validate and normalize the wide range of emotions, thoughts, and behaviors that are commonly experienced during grief. Reassure the person that their reactions are understandable and within the spectrum of normal grief responses.

Redirection Towards Adaptation and Equilibrium: Guide individuals in channeling their emotional energy towards adapting to a life altered by the loss. Support them in developing new routines, adjusting to changes, and working towards establishing a sense of balance and equilibrium in their lives.

Promote Supportive Networks: Underscore the importance of seeking and utilizing supportive networks. Encourage the bereaved to connect with helpful individuals, including friends, family members, or specialized support organizations, to foster a sense of community and belonging during their grieving process.

Bereavement Counseling for Individuals Facing AIDS/Cancer

Facilitate Acceptance of Mortality: Assist both the patient and their family in moving towards acceptance of the reality of death. Address their fears and anxieties surrounding death, and explore ways to provide comfort and alleviate distress.

Encourage Life Reflection: Encourage patients to reflect on their life, focusing on their achievements, meaningful experiences, and cherished memories. Help them identify and connect with sources of support, such as friends and family, to share these reflections.

Provide Symptom Management Information: Offer practical information and guidance on effectively managing distressing physical symptoms associated with their illness. This aims to enhance comfort, alleviate suffering, and improve their overall quality of life in their remaining time.

Explore Spiritual and Cultural Beliefs: Respect and explore the patient’s religious and cultural beliefs and practices. Facilitate connections with appropriate sources of spiritual support, such as chaplains or religious leaders, to provide comfort and meaning within their belief system.

Family Future Discussions: Create a supportive space to discuss the patient’s concerns and anxieties about their family’s future well-being after their death. Encourage open and honest dialogue and facilitate planning for practical and emotional aspects of the family’s future.

Bereavement Counseling After Death

Encourage Presence and Farewell Rituals: Support family members in spending as much time as they need with the deceased after death, respecting their individual needs for saying goodbye in a way that feels meaningful to them.

Sensitive Communication: Use the deceased person’s name in conversations to maintain their personhood, rather than using impersonal terms. Provide detailed information about the circumstances of death if the family was not present, addressing potential uncertainties and questions sensitively.

Facilitate Narrative Sharing: Encourage family members to share and retell the story of the deceased’s illness and death experience. This narrative process aids in processing the reality of the loss and integrating the experience into their grief journey.

Involve and Explain to Children: Include children in family discussions about the death, providing age-appropriate explanations about what has happened. This helps children understand the situation and cope with their grief in a supported environment.

Continuous Counseling After Death

Memory Reminders: Encourage the bereaved to use tangible reminders, such as photographs, memory boxes, or keepsakes, to actively remember the deceased and cherish positive memories.

Extended Support Network Engagement: Involve the extended support network, including family, friends, or trained volunteers, to ensure continued visits and consistent emotional support for the bereaved in the weeks and months following the loss.

Foster Open Communication: Cultivate an environment where family members feel safe and encouraged to openly express the full spectrum of their emotions, including guilt, relief, pain, or anger, fostering mutual understanding and strengthening family support.

Active Listening Emphasis: Prioritize active listening skills during counseling sessions, focusing on attentively hearing and understanding the bereaved person’s experiences and emotions, rather than dominating the conversation with excessive talking.

Discourage Hasty Decisions: Advise against making major life-altering decisions in the immediate aftermath of bereavement. Emphasize waiting until the initial intensity of grief subsides to ensure decisions are made with clearer judgment and consideration of practical implications.

Support Grieving Rituals: Acknowledge and support the bereaved person’s use of personal, cultural, or religious rituals and traditions that can aid in the grieving process, respecting their individual and cultural customs.

Counselor Self-Awareness: Maintain ongoing self-reflection and awareness of the counselor’s own experiences with loss and personal emotions. This self-awareness is crucial to ensure the counselor remains empathetic, objective, and fully focused on the needs of the bereaved individual.

Remember Significant Dates: Make a conscious effort to remember and acknowledge important dates, such as the deceased’s birthday and death anniversary, by reaching out to the bereaved to offer continued support and remembrance on these potentially difficult occasions.

Promote Emotional Well-being: Encourage self-care practices that support emotional well-being, such as relaxation techniques, engaging in social activities, and maintaining a healthy lifestyle. Remind the bereaved of the importance of prioritizing their own physical and emotional health during the grieving process.

Complications of Grief

Chronic Depression: Prolonged and persistent experience of major depressive disorder, characterized by symptoms such as deep sadness, pervasive hopelessness, and a marked loss of interest or pleasure in activities that were once enjoyable.

Substance Abuse: Development of substance use disorders, where individuals turn to drugs or alcohol as a maladaptive coping mechanism to numb or escape the intense pain of grief, potentially leading to dependence and addiction.

Suicidal Behavior: Expression of suicidal thoughts, ideation, or engaging in actions that indicate a serious risk of self-harm, requiring immediate intervention and urgent professional mental health support.

Prolonged Grief Disorder: Experiencing grief symptoms that are unusually intense and persistent, extending far beyond typical grieving periods, significantly impairing daily functioning, and indicating difficulty adjusting to life after loss.

Chronic Physical Symptoms: Development of persistent physical symptoms, such as chronic headaches, unexplained stomachaches, or persistent fatigue, where no identifiable medical cause can be found, suggesting a somatization of unresolved grief.

Severe Disease Exacerbation: Worsening or onset of pre-existing chronic or severe physical health conditions, potentially triggered or aggravated by the intense stress and emotional burden associated with prolonged grief.

Risk-Taking Behavior: Engagement in reckless or dangerous activities, potentially as a way to cope with or escape the pain of grief, or reflecting a diminished sense of self-preservation.

Persistent Sleep Disorders: Development of chronic sleep disturbances, such as severe insomnia or recurring nightmares, that significantly disrupt daily life and overall well-being.

Persistent Denial: Prolonged and rigid refusal to accept or acknowledge the reality of the loss, often manifesting as avoidance of any discussions or reminders related to the deceased or the loss event.

Identification with the Deceased: Unconsciously adopting symptoms, mannerisms, or behaviors that were characteristic of the deceased person, potentially as a way to maintain a connection or cope with the loss of identity associated with grief.

The Role of the Nurse in Grief and Bereavement

Nurses have a vital role in providing holistic care and support to individuals and families experiencing grief and bereavement. Key nursing responsibilities include:

Active Listening Provision: Nurses offer empathetic and active listening, creating a safe and supportive space for individuals to openly express their emotions, thoughts, and concerns related to their loss without judgment or interruption.

Future Exploration Support: Nurses gently encourage patients to explore and consider what their future may look like in the absence of the deceased, helping them envision possibilities for moving forward and finding hope amidst their grief.

Social Support Assessment and Enhancement: Nurses thoroughly assess the patient’s existing social support systems and actively assist them in:

Identifying available support networks.

Developing and strengthening connections with family members, friends, or relevant support groups to combat isolation and foster a sense of community.

Facilitating Time with the Deceased: Nurses respectfully honor the bereaved’s wishes to spend time with the body of the deceased at the time of death, when culturally and practically appropriate, facilitating opportunities for final goodbyes, rituals, and closure.

Respectful Validation of Feelings: Nurses demonstrate respect for and validate the full range of emotions experienced by grieving individuals. They acknowledge that each person’s grief journey is unique and valid, avoiding judgment or minimizing their pain.

Grief Manifestation Identification and Normalization: Nurses play a key role in identifying the diverse manifestations of grief, which can include:

Emotional symptoms (sadness, anger, anxiety).

Physical symptoms (fatigue, sleep disturbances, somatic complaints).

Cognitive symptoms (confusion, difficulty concentrating).

Nurses help patients understand and normalize these grief manifestations, reassuring them that these reactions are understandable and a natural part of the grieving process.

Meaning of Loss Identification Assistance: Nurses compassionately assist survivors in exploring and identifying the practical implications and personal meaning of their loss. This includes supporting them in:

Navigating the practical challenges and adjustments that arise from bereavement.

Finding personal meaning and purpose in life after loss.

Grief and Bereavement in Children

Introduction:

School-aged children require specialized attention and support when bereaved, particularly following the death of a parent, which differs from the support needed for preschoolers.

The experience of grief in children is highly individualized and shaped by various factors:

Age and developmental stage

Past experiences with loss

Individual personality and temperament

Children may express their grief in diverse ways, including:

Overtly expressing sadness through crying and tearfulness.

Seeking solitude and withdrawing from social interactions.

Experiencing a deep and pervasive sense of sadness and feeling the absence of the deceased as a significant void in their lives.

Even when children’s outward reactions to grief are not readily visible or easily interpreted by adults, it is crucial to recognize that:

The pain of loss remains consistent, regardless of whether it is overtly expressed.

Children may internalize grief or express it through behavioral changes rather than direct emotional displays.

It is important to note that many children are not encouraged or given adequate opportunities to grieve openly and immediately following a loss. However, the impact of unresolved childhood grief can manifest later in life:

As children grow older, the unprocessed sense of loss may resurface, often expressed in different ways, even into adulthood, potentially impacting emotional well-being and relationships.

Concept of Grief and Loss in Children:

Children’s capacity to comprehend and cope with death and loss is intrinsically linked to their age and stage of cognitive development.

Children are exposed to the concept of death through various everyday experiences:

Observing dead animals (pets, insects).

Media portrayals of death on television and in films.

Hearing about death in their homes, schools, and wider communities.

Children living with chronic illnesses, such as HIV, may have a heightened awareness of mortality and may have already experienced multiple losses in their young lives, potentially shaping their understanding and response to death.

Following a significant death, particularly that of a close family member, children have fundamental needs that must be addressed to support their grieving process:

Information: They require honest and age-appropriate information about death and what has happened.

Reassurance: They need consistent reassurance of love, safety, and security amidst their grief.

Safe Space for Expression: They need a secure and supportive environment where they feel safe to express their feelings, whether through words, play, or art.

Participation in Counseling: Age-appropriate counseling and therapeutic interventions can be beneficial in helping children process their grief in a healthy way.

Common Reactions of Bereavement in Children:

Children’s reactions to bereavement are diverse and influenced by:

Their chronological age

Their individual developmental stage

Their immediate environment and support systems

A child’s understanding of death evolves as they grow older, progressing through different cognitive stages:

Children aged 0-2 years (Infancy to Toddlerhood):

Understanding of Loss: At this stage, children primarily experience loss through the loss of physical contact, security, and consistent comfort associated with a primary caregiver’s death.

Behavioral Manifestations: Upset may be expressed through:

Changes in sleeping patterns (insomnia, increased sleepiness).

Alterations in eating habits (poor appetite, feeding difficulties).

Increased crying and fussiness.

Irritability and heightened emotional reactivity.

Social withdrawal and reduced engagement with caregivers.

Children aged 3-6 years (Preschool Age):

Understanding of Death: Children in this age group are typically unable to fully comprehend death as a permanent and irreversible state. They may:

Expect the deceased person to return, lacking a grasp of finality.

Exhibit confusion between reality and fantasy, sometimes attributing death to magical thinking or supernatural causes.

Emotional Expression: Grief may be expressed in intermittent bursts, fluctuating between periods of apparent sadness and periods where they seem to have “forgotten” the death, only to become upset again later, reflecting their fluctuating comprehension and emotional processing.

Children aged 6-9 years (Early Elementary School Age):

Understanding of Death: Children in this age group begin to grasp that death is permanent and universal. They understand that:

Death is not reversible; it is a final event.

Death is universal; all living things eventually die.

However, they may still struggle to fully accept death as personally inevitable and may imagine it is avoidable or only happens to others.

Practical Interest: They often develop a heightened interest in the practical and concrete aspects of death, becoming curious about:

What happens to the deceased person’s body after death.

Funeral rituals and burial practices.

Responsibility and Guilt: Children in this age group may experience feelings of personal responsibility or guilt related to the death, believing that their actions, thoughts, or behaviors may have somehow caused or contributed to the death.

Children aged 9-12 years (Late Elementary/Early Middle School Age):

Understanding of Death: Children in this age range possess a level of understanding of death that is increasingly similar to that of adults. They fully recognize that:

Death is universal; it happens to everyone eventually.

Death is unavoidable; it is an inevitable part of life.

Death is permanent; it is not reversible.

They also begin to understand that death can be sudden and unexpected, not just associated with old age or illness.

Existential Concerns: They may start to grapple with existential questions related to:

Their own mortality and the concept of their own death.

The broader meaning of life and what happens after death, engaging in more abstract thinking about mortality.

Adolescents (Teenage Years):

Understanding of Death: Adolescents typically have a fully developed, adult-level understanding of death, recognizing its finality, universality, and inevitability.

Risk-Taking Behaviors: In some cases, adolescents may engage in risk-taking behaviors as a way to:

Explore their own mortality and confront their fears about death.

Test boundaries and assert independence, which can be a part of adolescent development.

Practical Ways to Support a Grieving Child:

Storytelling as a Tool: Utilize storytelling as a therapeutic technique to help children:

Process the complex emotions associated with loss.

Understand and make sense of the grieving process.

Navigate the transitions and changes brought about by bereavement.

Extensive Support and Counseling: Provide comprehensive and ongoing support and counseling to guide children through the bereavement period. This is essential to:

Help them process their grief in a healthy and adaptive way.

Facilitate their gradual transition back to a sense of normalcy and routine.

Prevent the development of complicated grief or long-term emotional difficulties.

Open Communication and Emotional Expression: Encourage open communication within the family unit and create safe channels for children to express their emotions in various forms:

Verbal expression of feelings and thoughts.

Creative outlets such as drawing, painting, or other art forms.

Writing in journals or expressing themselves through poetry or stories.

Therapeutic play activities that allow for symbolic expression of grief and loss.

Preparation and Truthfulness: Prioritize honesty and age-appropriate preparation when discussing death with children:

Explain the truth about the loss in simple, direct, and honest terms that are suitable for their developmental level.

Avoid euphemisms or vague language that may confuse or frighten children.

Adequate preparation helps children process loss more effectively. An unprepared child may experience:

Overwhelm and intense distress when faced with sudden loss.

Shock and confusion due to lack of understanding.

Coping Skills Development: Actively help children develop healthy and adaptive coping mechanisms to navigate their grief journey. This involves:

Providing age-appropriate guidance and support during counseling sessions.

Teaching specific coping skills, such as relaxation techniques, emotional regulation strategies, and problem-solving skills, tailored to their developmental level.

Age-Appropriate Communication: Ensure all communication with children about death and grief is carefully tailored to their age and cognitive abilities. This includes:

Using language and concepts that are easily understandable for their age.

Actively listening to children and responding to their questions and concerns in a way that is developmentally appropriate.

Consistency and Stability: Maintain consistency and stability in the child’s daily routine and home environment as much as possible. Recognizing that grieving children are already experiencing significant changes and instability due to loss, it is crucial to:

Minimize further disruptions to their familiar routines.

Provide a predictable and secure environment.

Be aware that grieving children may face multiple losses concurrently, such as:

Changes in schooling due to relocation or financial strain.

Separation from their familiar home environment if they need to move.

Individualized Approach: Adopt an individualized approach to grief support, recognizing that:

Each child grieves in their own unique way and at their own pace.

Respect and accommodate their individual needs, emotional expression styles, and coping mechanisms.

Avoid imposing adult expectations or timelines on a child’s grieving process.

Active Listening and Empathy: Prioritize active listening skills and demonstrate genuine empathy in all interactions with grieving children. This involves:

Assuring the child that you are fully present and attentively listening to them.

Conveying genuine care and concern for their feelings and experiences at any given moment, validating their emotions without judgment.

Normalizing Death through Nature: Help children understand and normalize death as a natural part of the life cycle by:

Relating the concept of death to examples from the natural world that are familiar and relatable to children.

Using examples such as the life cycle of flowers, the falling of leaves in autumn, or the natural death of animals to help them grasp the universality and inevitability of death in nature.

This can aid in demystifying death and making it less frightening and more understandable.

Patience and Understanding: Recognize that children’s grief responses are varied and may fluctuate over time. Caregivers and professionals need to exercise:

Patience in allowing children to grieve in their own way and timeframe.

Understanding for the often unpredictable and non-linear nature of children’s grieving processes.

Offering Involvement and Choices: Empower grieving children by offering them choices and opportunities to participate in rituals or processes related to death and mourning, such as:

Offering the choice to visit the hospital or hospice setting if appropriate and desired.

Giving them the option to view the body of the deceased if they wish.

Offering the choice to attend the funeral or memorial service if they feel comfortable.

Empowering them to make choices and participate based on their individual comfort level and preferences, fostering a sense of agency and control in a difficult situation.

School Continuity and Support: Encourage a sense of continuity and normalcy in the child’s life, particularly regarding their schooling. Emphasize the importance of:

Maintaining consistent school attendance and engagement in learning.

School can provide a structured routine, social interaction, and a sense of normalcy, which can be particularly helpful for grieving children in re-establishing a sense of stability in their lives.

Liaison with school staff to ensure they are aware of the child’s bereavement and can provide additional support and understanding within the school environment.

Things to Say to Children About Death:

Universality and Inevitability: Explain that death is a universal and inevitable part of life, using relatable examples from nature such as flowers, leaves, and animals to illustrate this natural process.

Unpredictability of Death: Acknowledge that death can be unpredictable and may occur at any age, not just in old age.

Validate Wishes: Assure children that it is okay and normal to wish that the person had not died, validating their feelings of longing and sadness.

Validate Emotions: Validate and acknowledge the full range of their emotions, including sadness and anger, assuring them that these feelings are normal and acceptable responses to loss.

Religious/Spiritual Beliefs: If appropriate and aligned with the family’s beliefs, encourage reliance on religion and spiritual beliefs as a source of comfort, strength, and understanding in accepting and processing the concept of death.

Use Direct Language: Do not shy away from using direct and clear language when talking about death. Use words like “dead” or “death” rather than euphemisms that can be confusing or misleading to children.

Reassure about Responsibility: Reassure children explicitly that they had absolutely nothing to do with causing the death, addressing potential feelings of guilt or self-blame that children often experience.

Honesty about Unknowns: Be honest and transparent about not having all the answers to their questions about death or the afterlife. It is okay to say “I don’t know” when you don’t have an answer, fostering trust through honesty.

Highlight Continuity: Emphasize aspects of their life that will remain unchanged and stable despite the loss, such as:

Their familiar home environment and room.

Their school routine and classmates.

Their toys and cherished possessions.

Their friendships and social connections.

Life Continues After Pain: Convey the message of hope and resilience, assuring children that life does continue even after experiencing pain and loss. Reassure them that while grief is painful, there will be happy times again in the future, and they will learn to find joy and meaning in life even after loss.

Things Not to Say to Children About Death:

Avoid Euphemisms for Death: Avoid using euphemisms for death, such as saying the deceased is “sleeping” or has been “lost.” These phrases can be confusing and potentially frightening for children, who may develop anxieties about sleep or getting lost.

Don’t Imply Choice in Death: Refrain from suggesting that the deceased “wanted” to go to heaven or that death was a voluntary choice. This can be misinterpreted by children as abandonment or rejection, causing feelings of insecurity and questioning why they were “left behind.”

Don’t Suppress Emotion: Avoid trying to stop or minimize the grieving process by using phrases like “big boys don’t cry” or “be strong.” Allow children to express their grief naturally and openly, validating their emotions as healthy and necessary responses to loss. Suppressing grief can be emotionally damaging and hinder healthy coping.

Get in Touch

(+256) 790 036 252

(+256) 748 324 644

Info@nursesonlinediscussion.com

Kampala ,Uganda

© 2025 Nurses online discussion. All Rights Reserved Design & Developed by Opensigma.co