Terminal Care

Subtopic:

Euthanasia

Euthanasia is defined as the deliberate and intentional act of ending a person’s life with the primary motive of relieving their pain and suffering.

The term “euthanasia” originates from the Greek words “Eu” and “Thanatosis,” which combined mean “Good Death” or “Gentle and Easy Death.” Historically, it has sometimes been referred to as “mercy killing”.

At its core, euthanasia involves taking direct action to terminate a human life. This can be carried out through different means, such as:

Administering a lethal injection of medication.

Withholding or withdrawing life-sustaining medical treatment that is necessary to maintain life.

The term “euthanasia” was first introduced into the medical lexicon by Francis Bacon in the 17th century. In this early medical context, Bacon described euthanasia as the physician’s duty to alleviate physical suffering and facilitate a painless and peaceful death for patients facing incurable and agonizing illnesses

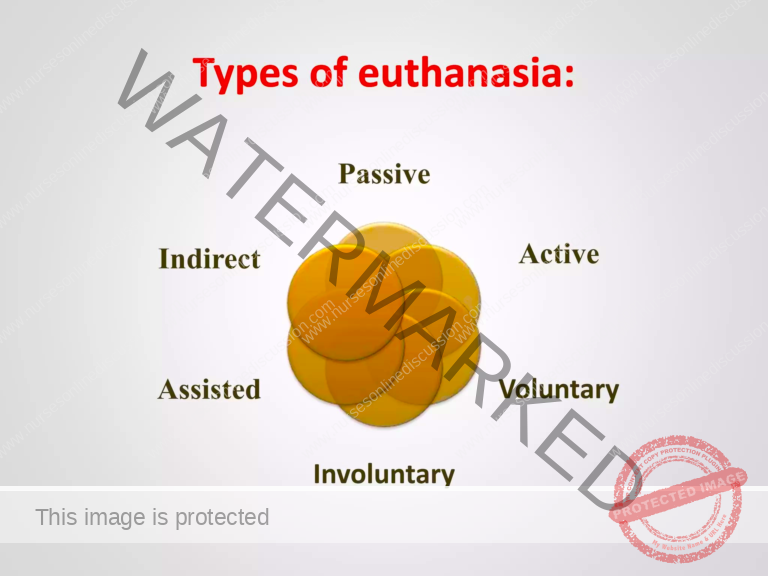

Types of Euthanasia

Euthanasia is not a monolithic concept; it encompasses different categories based on the manner of action and the patient’s consent. The primary types of euthanasia are:

Active Euthanasia

Definition: Death is intentionally brought about by a direct and active intervention. This typically involves the administration of a lethal agent to directly cause death.

Example: Administering a high and lethal dose of medication to a patient with the express intention of ending their life. This action can be performed by a physician (physician-administered euthanasia) or by the individual themselves, sometimes with assistance (assisted suicide).

Passive Euthanasia

Definition: Death is brought about by omission or withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment, rather than a direct action to cause death. Death results from the underlying disease process, allowed to progress naturally without medical intervention to prolong life.

Examples:

Withdrawing Treatment: Discontinuing life-sustaining medical interventions that are currently in place, such as turning off a mechanical ventilator that is artificially supporting breathing, or stopping dialysis treatment for kidney failure.

Withholding Treatment: Refraining from initiating or providing medical treatments that are deemed to be life-prolonging, but not curative, in a terminal illness. For example, choosing not to perform surgery that might extend a patient’s life for a short period but would not address the underlying terminal condition.

Voluntary Euthanasia

Definition: Euthanasia is considered voluntary when it is carried out with the explicit and informed consent of the patient. The patient willingly and autonomously requests and cooperates with the act of ending their life.

Example: A competent and informed patient with a terminal illness makes a clear and autonomous decision to end their life and actively requests and consents to assistance in doing so. There is no coercion or external pressure influencing their decision.

Non-Voluntary Euthanasia

Definition: Euthanasia becomes non-voluntary when the decision to end a patient’s life is made on behalf of a patient who lacks the capacity to make the decision for themselves, typically because they are unconscious, cognitively incapacitated, or otherwise unable to express their wishes.

Example: In cases where a patient is in a persistent vegetative state or is permanently unconscious and unable to express their wishes, an appropriate surrogate decision-maker, such as a legal guardian or designated family member, makes the decision to withdraw life support, believing it to be in the patient’s best interest or aligned with their presumed values. Non-voluntary euthanasia is often ethically complex and legally restricted. It is sometimes framed as acting in the patient’s “best interest” or as a “favor” to end their suffering, although this characterization remains ethically debated.

Indirect Euthanasia

Definition: Death is not the direct intention, but is an unintended but foreseeable consequence of treatments administered primarily to alleviate pain and suffering. Treatments are given with the primary goal of comfort, but may have the secondary effect of hastening death.

Example: Administering high doses of pain-relieving medications, such as opioids like morphine, with the primary intention of alleviating intractable pain in a terminally ill patient. While the primary goal is pain relief (beneficence), a known side effect of high-dose opioids is respiratory depression, which, in a vulnerable patient, may inadvertently hasten death. In indirect euthanasia, the intent is comfort, not death, even if death is a foreseeable consequence of aggressive pain management.

Religious Perspectives on Euthanasia

Major world religions hold diverse views on euthanasia, reflecting varying theological and ethical frameworks:

Islam:

Core Beliefs: Islamic teachings generally oppose euthanasia in all its forms. Life is considered sacred, a gift from Allah, and under Allah’s sole control. Intentionally ending a life is viewed as a transgression against God’s will.

Permissible Exceptions: The Islamic Medical Association of America (IMANA), while generally opposing euthanasia, makes a limited exception for the discontinuation of mechanical life support in cases where a patient is in a persistent vegetative state (PVS). In PVS, where there is no reasonable hope of recovery of consciousness, withdrawing artificial life support may be considered permissible by some Islamic scholars, viewed as allowing a natural death to occur rather than actively ending a life.

Christianity:

General Stance: Most Christian denominations and traditions oppose euthanasia, upholding the sanctity of life doctrine. Christian theology emphasizes the inherent value of human life as created in God’s image.

Ethical Emphasis: Many Christian churches and denominations stress the importance of not actively interfering with the natural process of death. They emphasize respecting human life as a sacred gift from God, and believe that only God has the right to take life. Focus is often placed on providing compassionate care, pain management, and spiritual support for the dying, rather than actively hastening death.

Judaism:

Diverse Views: Jewish medical ethics present a range of views on euthanasia and end-of-life treatment decisions, reflecting the diversity of Jewish thought and interpretation of Jewish law.

Acceptance of Passive Euthanasia: While generally opposing active euthanasia, some branches of Judaism and Jewish medical ethicists support voluntary passive euthanasia under very specific and limited circumstances. This may include allowing a natural death to occur by withholding or withdrawing extraordinary life support measures in cases of terminal illness and intractable suffering, but actively intervening to cause death is generally prohibited.

Shinto:

Cultural Context: In Japan, where Shintoism is a dominant indigenous religion, cultural and religious views on end-of-life care are nuanced.

Support for Passive Voluntary Euthanasia: A majority of Shinto-influenced religious organizations in Japan are reported to be in agreement with voluntary passive euthanasia under specific conditions, reflecting a cultural acceptance of allowing natural death in certain circumstances.

Discouragement of Artificial Prolongation: Shintoism, in general, tends to discourage artificial prolongation of life when death is deemed inevitable and suffering is prolonged. There is a greater emphasis on accepting the natural cycle of life and death.

Buddhism:

Compassion as Justification: Compassion (Karuna) is a central and core value in Buddhist teachings and ethics. This principle of compassion can sometimes be invoked to justify euthanasia in situations where the primary intention is to relieve unbearable suffering and prevent further pain.

Moral Boundaries and Restrictions: Despite the emphasis on compassion, Buddhism generally maintains strong moral restrictions against taking actions specifically aimed at destroying human life, reflecting the principle of non-harming (Ahimsa). Euthanasia, even if motivated by compassion, is viewed by many Buddhist traditions as violating this fundamental moral precept. The ethical permissibility of euthanasia in Buddhism remains a complex and debated topic, with varying interpretations and stances across different Buddhist schools of thought.

Nurses’ Roles in Euthanasia (Where Legally Permitted):

In jurisdictions where euthanasia or physician-assisted suicide is legal and practiced under specific regulations, nurses may have defined roles in the process, typically categorized into three phases:

Phase I: Pre-Euthanasia (Assessment and Consent)

Assessment:

Active Listening to Patient Request: Listen attentively and empathetically to the patient’s request for euthanasia, creating a safe and non-judgmental space for them to express their wishes and underlying motivations.

Explore Underlying Reasons: Thoroughly assess the underlying reasons for the patient’s request. Explore contributing factors driving their desire for hastened death, such as:

Unrelievable pain and suffering.

Loss of dignity and autonomy.

Fear of further decline or loss of control.

Existential distress and hopelessness.

Evaluate Patient Knowledge: Assess the patient’s level of knowledge and understanding regarding:

Their medical diagnosis and prognosis.

Available treatment options, including palliative care alternatives to euthanasia.

General Condition and Physical Examination: Conduct a comprehensive assessment of the patient’s:

Overall general condition, functional status, and level of debility.

Detailed physical examination to document current physical symptoms and clinical status.

Severity and impact of their underlying illness on their quality of life.

Family Reaction Assessment: Carefully evaluate the patient’s family’s reaction to the request for euthanasia, recognizing the potential for diverse perspectives and emotional responses within the family.

Encourage open communication and dialogue between the patient and family members.

Identify and assess the family’s needs for information, support, and counseling during this sensitive process.

Consultation and Team Review: Nurses play a crucial role as patient advocates by participating in:

Presenting the patient’s case and their request for euthanasia to a multidisciplinary panel of experts.

Representing the patient’s condition, wishes, and the family’s perspectives to the expert panel for ethical review and decision-making.

The expert panel typically includes clinical psychologists, social workers, nurses, physicians, ethicists, and potentially spiritual care providers, ensuring a holistic and ethically sound evaluation.

Written Consent Process: When euthanasia is deemed ethically and legally appropriate and the patient’s request proceeds, nurses are involved in ensuring a rigorous and ethically sound consent process:

Quiet and Non-Disturbing Environment: Ensure the consent process takes place in a private, quiet, and non-disturbing environment, minimizing external pressures and distractions.

Non-Threatening Explanation: Explain the consent process and the nature of the document in a non-threatening and supportive tone, ensuring the patient feels safe and respected.

Time for Questions: Allow ample time for the patient and family to ask questions, express concerns, and seek clarification about the euthanasia process, ensuring fully informed consent.

Full Understanding Verification: Ensure that both the patient and their family fully understand:

The detailed euthanasia procedure and what it entails.

Potential physical or emotional discomfort that may be experienced during the process.

The patient’s absolute right to revoke their request at any point, even after providing initial consent, reinforcing patient autonomy and control.

Establish a clearly defined specified period within which the patient retains the right to revoke their request, ensuring ample time for reconsideration.

Phase II: Intra-Euthanasia (During the Procedure)

Preparation for Procedure: Nurses play a vital role in the practical preparation for the euthanasia procedure:

Establish IV Access: Establish reliable intravenous (IV) access to facilitate medication administration during the procedure.

Procedure Reiteration: Clearly reiterate the step-by-step procedure to both the patient and any family members present, providing reassurance and addressing any last-minute questions.

Medication Preparation Assistance: Assist the physician in preparing the necessary medications for euthanasia, which typically include:

Sedatives to induce deep sedation and unconsciousness.

Analgesics for pain relief and comfort.

Euthanatic agents, the specific medication(s) that will ultimately induce death.

Ensure all medications are accurately prepared and clearly labeled to prevent medication errors.

Premedication Administration: Administer premedication, such as midazolam (a sedative), if the patient explicitly wishes to be unaware of the moment of coma induction, respecting their desire for a less conscious experience during the initial stages.

Assistance During Procedure: Nurses provide direct assistance and support during the euthanasia procedure itself:

Emergency Set Preparation: Prepare a readily available emergency set of medications and equipment as per established institutional protocols, ensuring preparedness for any unforeseen complications.

Family Emotional Support: Offer compassionate emotional support to family members who may be present during the procedure, acknowledging their grief and providing comfort.

Documentation and Record-Keeping: Meticulous and accurate record-keeping is essential throughout the euthanasia process. Nurses are responsible for:

Maintaining a detailed record of all medications used during the procedure, including drug names, dosages, and administration times, ensuring accurate documentation.

Documenting all significant events that occur during the procedure, including patient responses, vital signs, and any unexpected occurrences.

Recording the names and roles of all personnel involved in the euthanasia procedure, ensuring accountability and transparency.

Completing all required documentation forms, including:

Signed and witnessed consent forms confirming informed patient consent.

Pain assessment records documenting pre-procedural pain levels and symptom burden.

Specific euthanasia record forms mandated by institutional or legal guidelines.

The last office chart entry, documenting the time and circumstances of death and all relevant details of the euthanasia procedure.

Phase III: Post-Euthanasia (After Death)

Certifying Death: After the physician has officially certified the patient’s death, nurses play a role in:

Clearly explaining to the family that the euthanasia procedure has been completed and that death has occurred, providing factual and compassionate information.

Family Bereavement Support: Provide ongoing emotional support to the patient’s family in the immediate aftermath of euthanasia, recognizing that they may experience a complex mix of emotions, including:

Grief and sadness over the loss of their loved one.

Guilt or uncertainty about the decision, even if it was made with the patient’s consent.

Offer reassurance and validation of their grief, creating a safe space for them to express their feelings without judgment.

Utilize effective communication and counseling skills to address their immediate emotional needs, offering empathetic listening and support.

Consider making a timely referral to a professional counselor or bereavement specialist for family members who may be experiencing uncontrolled or overwhelming emotions, ensuring access to specialized grief support.

Safe Disposal of Euthanatic Agents: Ensure the safe and responsible disposal of all unused euthanatic agents. Nurses are responsible for:

Returning all unused portions of euthanatic medications to the pharmacy department for proper and secure disposal, adhering to established protocols for controlled substances.

Preventing improper use or diversion of euthanatic agents by ensuring they are handled and disposed of according to strict regulations and institutional policies.

Incident Evaluation (If Necessary): In rare cases where unexpected problems or complications occur during the euthanasia procedure, such as suspected underdosing or technical difficulties, nurses may be involved in:

Completing an incident evaluation form to document any unexpected events or deviations from the planned procedure.

Contributing to a review process aimed at identifying potential system improvements or procedural refinements to prevent similar issues in the future, ensuring continuous quality improvement in end-of-life care protocols.

Ethical Dilemmas Surrounding Euthanasia

An ethical dilemma in euthanasia arises when there is a fundamental conflict between deeply held ethical principles, values, or moral beliefs in the context of end-of-life decisions and the practice of intentionally hastening death for a person experiencing intractable suffering.

These ethical dilemmas often stem from the inherent tension and competing values among core ethical principles, such as:

Autonomy: The ethical principle of patient autonomy, recognizing the right of individuals to self-determination and control over their own bodies and lives, including healthcare decisions.

Beneficence: The ethical duty of healthcare professionals to act in the best interests of their patients and to actively promote their well-being, including alleviating suffering and improving quality of life.

Non-Maleficence: The ethical obligation to “do no harm” (Primum non nocere), requiring healthcare professionals to avoid causing harm or acting in ways that could negatively impact patient well-being.

Sanctity of Life: The deeply held belief, often rooted in religious or philosophical convictions, that human life is inherently valuable, sacred, and should be protected and preserved, regardless of condition or perceived quality of life.

These fundamental ethical principles can come into direct conflict when considering euthanasia, creating complex and emotionally challenging dilemmas. Some common manifestations of these ethical dilemmas include:

Balancing Autonomy and Sanctity of Life: The central ethical dilemma often revolves around the inherent tension between:

Patient Autonomy: The ethical imperative to respect an individual’s right to make autonomous choices about their own life and death, particularly when facing unbearable suffering from a terminal illness.

Sanctity of Life: The deeply held belief in the intrinsic value and sacredness of human life, which often leads to opposition to any intentional act to end a life, even with patient consent and for compassionate reasons.

Example: A patient with a terminal illness expresses a clear and persistent desire to end their life through euthanasia to avoid further suffering, invoking their right to autonomy and self-determination. However, healthcare professionals and family members who hold strong beliefs in the sanctity of life may experience a profound ethical and moral conflict in honoring the patient’s autonomous request to assist in euthanasia, struggling to reconcile patient autonomy with their own deeply held values.

Role of Healthcare Professionals and Moral Integrity: Healthcare professionals frequently confront ethical dilemmas when their personal moral beliefs and values come into conflict with their professional duty to provide patient-centered care and alleviate suffering. Some healthcare providers may have deeply held moral, ethical, or religious objections to participating in euthanasia, viewing it as morally wrong or incompatible with their professional role as healers. This conflict can create significant moral distress and internal conflict.

Example: A nurse who personally opposes euthanasia on moral or religious grounds may face an intense ethical dilemma when asked to actively participate in the euthanasia procedure by administering medication intended to hasten a patient’s death. The nurse must navigate the conflict between their personal moral convictions and their professional responsibilities to respect patient autonomy and provide compassionate care, even when it conflicts with their own values.

Palliative Care Accessibility and Quality: The availability and quality of palliative care services in a given region or healthcare system can significantly influence the ethical considerations surrounding euthanasia. If individuals lack access to comprehensive and high-quality palliative care, they may feel compelled to consider euthanasia as a more appealing option for relief from suffering, particularly if their pain and symptoms are not adequately managed through conventional medical approaches. This raises ethical questions about the healthcare system’s responsibility to ensure equitable access to palliative care as a fundamental component of end-of-life care.

Example: A patient with a terminal illness who is experiencing severe and intractable pain, and who has limited access to specialized palliative care services that could effectively manage their pain and other distressing symptoms, may perceive euthanasia as their only viable option for finding relief from unbearable suffering. This situation raises ethical questions about the healthcare system’s obligation to provide comprehensive and accessible palliative care to all patients, ensuring that euthanasia is not considered due to lack of access to adequate comfort-focused care.

Psychological Impact and Moral Distress: Euthanasia, as a profound and ethically charged act, can have a significant psychological impact on healthcare professionals who are directly or indirectly involved in the process. It can also deeply affect family members and loved ones of the patient, potentially leading to:

Moral distress and emotional burden for healthcare professionals who participate, even when acting within legal and ethical guidelines.

Guilt, grief, and emotional trauma for family members who witness or are involved in the decision-making process.

This raises ethical concerns about the potential for psychological harm and the need for adequate support and resources for all individuals involved in euthanasia decisions and procedures.

Example: A physician who performs euthanasia on a patient, even with informed consent and adherence to all legal and ethical safeguards, may still experience significant emotional distress and moral conflict afterward. They may question the rightness of their decision, grapple with feelings of guilt or doubt, and require access to counseling or peer support to process the emotional weight of their involvement in ending a life, even in a legally and ethically sanctioned context.

Subjectivity of Suffering and Quality of Life Assessments: Evaluating the subjective experience of suffering and determining what constitutes an acceptable quality of life presents a profound ethical dilemma. Assessing whether a person’s suffering is truly “unbearable” and if their quality of life has “significantly deteriorated” inherently involves subjective judgments and deeply personal values that can vary widely among individuals, healthcare professionals, and families. There is no objective or universally agreed-upon metric for measuring subjective suffering or quality of life, making these determinations ethically complex and challenging.

Example: A patient with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) or Lou Gehrig’s disease may experience a gradual and progressive loss of motor function, eventually leading to severe physical disabilities, difficulties with breathing, swallowing, and communication, and chronic pain and discomfort. While objectively, their physical condition is severely compromised, and their independence and autonomy are significantly diminished, assessing their subjective quality of life becomes an ethical dilemma. Healthcare professionals, caregivers, and family members may hold differing perspectives on what constitutes an “unacceptable” quality of life in this context. Some may argue that the patient’s suffering is indeed unbearable, and their quality of life has deteriorated to a point where euthanasia is a compassionate option. Others may emphasize that even in the face of severe physical limitations and suffering, individuals can still find meaning, purpose, and joy in their lives, highlighting the importance of palliative care, psychological support, and interventions to alleviate suffering and enhance well-being, rather than resorting to euthanasia. The subjective nature of suffering and quality of life assessments underscores the ethical complexity of euthanasia decisions.

Safeguards and the Slippery Slope Argument: Establishing robust and effective safeguards and criteria to prevent potential abuse, coercion, or misuse of euthanasia is a critical ethical challenge. The “slippery slope” argument raises the concern that:

Legalizing euthanasia, even for narrowly defined cases of terminally ill patients experiencing unbearable suffering, may create a slippery slope effect.

This could potentially lead to a gradual expansion of euthanasia criteria over time, encompassing broader categories of individuals, such as those with chronic illnesses, disabilities, or psychiatric conditions, who may not be terminally ill.

Opponents fear that such expansion could ultimately open the door to abuse or even involuntary euthanasia, where individuals may be coerced or influenced into choosing euthanasia even when it is not truly their autonomous wish.

Example: In a hypothetical country where euthanasia is legally permitted for terminally ill patients experiencing unbearable suffering, a public debate arises about whether to expand the eligibility criteria to include individuals with chronic, non-terminal illnesses or psychiatric conditions who also experience significant and persistent suffering. Proponents of expansion argue that these individuals, while not imminently dying, may also endure comparable levels of suffering and should have the right to choose euthanasia as a means of relief. However, opponents of expansion express serious ethical concerns about the potential “slippery slope.” They fear that broadening the criteria beyond terminal illness may weaken safeguards, making it more difficult to prevent abuse, and potentially leading to a societal devaluation of the lives of individuals with chronic conditions or mental illness, who may be more vulnerable to coercion or undue influence in end-of-life decisions. The slippery slope argument highlights the ongoing ethical challenge of balancing individual autonomy with societal protections and preventing potential harms in the context of euthanasia legalization and practice.

We are a supportive platform dedicated to empowering student nurses and midwives through quality educational resources, career guidance, and a vibrant community. Join us to connect, learn, and grow in your healthcare journey

Quick Links

Our Courses

Legal / Policies

Get in Touch

(+256) 790 036 252

(+256) 748 324 644

Info@nursesonlinediscussion.com

Kampala ,Uganda

© 2025 Nurses online discussion. All Rights Reserved | Design & Developed by Opensigma