Conditions of the Ear and Nose

Subtopic:

Hearing impairment

Hearing impairment is characterized by a diminished ability to perceive sound. This condition, which can be either temporary or permanent, negatively impacts an individual’s capacity to detect and comprehend sounds. The degree of hearing loss can vary significantly, ranging from minor difficulty hearing soft sounds to a complete inability to hear.

Understanding the Process of Hearing

To understand hearing impairment, it’s helpful to first understand how normal hearing functions. The process begins when sound waves in the air reach the outer ear, also known as the pinna (the visible part of the ear). These waves then travel through:

Outer Ear:

Pinna: Collects and channels sound waves.

Ear Canal: Sound waves travel through the ear canal toward the middle ear.

Middle Ear:

Eardrum (Tympanic Membrane): Sound waves cause the eardrum, a thin layer of tissue, to vibrate.

Ossicles: These vibrations are amplified by three tiny bones called ossicles (malleus, incus, stapes). The ossicles transmit and magnify these vibrations to the inner ear.

Inner Ear:

Cochlea: The vibrations enter the inner ear and reach the cochlea, a spiral-shaped, fluid-filled chamber. The cochlea is lined with thousands of microscopic hair cells.

Outer Hair Cells: As vibrations travel through the fluid in the cochlea, outer hair cells enhance these vibrations. This amplification by outer hair cells is crucial for detecting faint sounds.

Inner Hair Cells: Inner hair cells then perform the crucial step of transduction. They convert the mechanical vibrations into electrical nerve impulses.

Auditory Nerve: These electrical signals are transmitted along the auditory nerve (also known as the cochlear nerve), which connects the inner ear to the brain.

Brain (Cerebrum):

Sound Interpretation: The auditory nerve carries the electrical impulses to the brain, specifically to the cerebrum (auditory cortex). Here, the brain interprets these impulses as recognizable sounds.

Pitch Detection: The cochlea is organized tonotopically, meaning different regions within the cochlea are sensitive to different sound frequencies or pitches. This is analogous to the keys on a piano, where each key corresponds to a specific pitch. This frequency-specific information is preserved as it is transmitted to the brain, allowing us to distinguish between different sounds.

Hearing Impairment: Understanding the Spectrum

Hearing impairment arises when there is damage or dysfunction in one or more parts of the auditory system, hindering the ability to perceive sound. It is formally defined as a reduction in hearing sensitivity, whether temporary or permanent, that negatively impacts an individual’s capacity to hear and, crucially, understand sounds. The extent of hearing loss varies widely, ranging from subtle difficulties to profound deafness.

To further clarify the spectrum of hearing impairment, several terms are used to describe different degrees and types of hearing loss:

Deafness:

Deafness signifies a severe to profound degree of hearing impairment.

It is characterized by such a significant loss of auditory function that an individual is unable to comprehend speech, even when sounds are amplified.

Individuals with deafness typically find that auditory linguistic information is inaccessible through hearing alone and often rely on visual communication methods such as sign language, lip-reading, or utilize assistive devices that do not depend on auditory input.

Amplification, in this context, refers to the use of hearing aids or other assistive listening technologies designed to boost sound volume. The definition of deafness emphasizes that even with the aid of amplification, speech understanding remains severely limited or impossible.

Hard of Hearing:

The term Hard of Hearing describes individuals who experience hearing loss ranging from mild to moderate.

People who are hard of hearing typically retain some residual hearing capacity.

They often benefit significantly from amplification devices, such as hearing aids or personal amplifiers, which enhance their ability to hear and understand speech and environmental sounds.

Hearing Loss:

Hearing Loss is a broad, general term used to describe any reduction in hearing sensitivity compared to normal hearing thresholds.

It is an overarching term encompassing the entire spectrum of hearing impairment, from mild to profound degrees of loss.

Hearing loss can be categorized by its duration (temporary or permanent), severity (mild to profound), and type (conductive, sensorineural, mixed).

Deafened:

Deafened is a term specifically used to refer to individuals who acquire a profound hearing loss later in life, typically as adults.

This term distinguishes individuals who become deaf after developing spoken language and relying on hearing for communication, contrasting with those born deaf or deafened early in childhood.

Deafened individuals may face unique challenges in adaptation and communication strategies compared to those with pre-lingual deafness, often having to adjust to a world previously navigated primarily through hearing.

Anacusis:

Anacusis is a medical term denoting total deafness.

Individuals with anacusis experience complete absence of hearing in one or both ears.

They possess no functional hearing whatsoever, even with maximal amplification.

Types of Hearing Loss: An Exploration

Hearing loss is categorized based on where the auditory system is affected. There are three primary classifications:

Conductive Hearing Loss:

Problem Location: This type of hearing loss arises from issues in the outer or middle ear. These problems hinder the efficient transmission of sound to the inner ear.

Mechanism of Disruption: The core issue lies in the sound conduction process. Sound vibrations are not effectively passed through the outer and middle ear to the inner ear structures.

Common Causes: Various conditions affecting the outer or middle ear can lead to conductive hearing loss. Examples include:

Ear Infections (Otitis Media): Infections in the middle ear space.

Ear Canal Obstructions: Blockages in the ear canal due to accumulated earwax, foreign bodies, or swelling.

Eardrum Issues: A hole or tear in the eardrum (tympanic membrane perforation).

Middle Ear Bone Abnormalities: Problems with the small bones (ossicles) of the middle ear, for instance:

Disruption of the ossicular chain’s continuity.

Otosclerosis – abnormal bone growth hindering ossicle movement.

Prevalence in Children: Otitis media with effusion, characterized by fluid buildup in the middle ear, is the most frequent cause of conductive hearing loss in children. The resulting hearing loss is typically mild to moderate.

Congenital Links: Certain birth conditions (congenital syndromes) can also be associated with abnormalities of the middle ear, potentially leading to conductive hearing loss. Examples include syndromes such as Apert, Crouzon, and Treacher Collins.

Sensorineural Hearing Loss (SNHL):

Problem Location: Sensorineural hearing loss originates from damage or malfunction within the inner ear (cochlea) itself or in the neural pathways of the auditory nerve. These pathways are essential for carrying sound signals to the brain.

Functional Impairment: The fundamental problem is with the sensory and neural aspects of hearing. Either the specialized hair cells within the cochlea are damaged, disrupting their ability to convert sound vibrations into electrical signals, or the auditory nerve pathways are compromised, hindering the transmission of these signals to the brain for interpretation.

Typical Permanence: Sensorineural hearing loss is frequently long-lasting or permanent, as damage to these delicate inner ear structures is often irreversible with current medical treatments.

Underlying Causes: SNHL is caused by damage or lesions affecting:

The cochlea, the sensory organ of hearing in the inner ear.

The auditory nerve, also known as the 8th cranial nerve.

The central auditory pathways within the brain, including the brainstem and auditory cortex.

Onset Categories: SNHL can be classified by when it develops: it can be either acquired (occurring after birth) or congenital (present at birth), with both being equally common.

Acquired SNHL Etiologies: The most prevalent postnatal cause of acquired SNHL is meningitis. Other postnatal causes encompass:

Premature birth and associated complications.

Severe jaundice (hyperbilirubinemia) in newborns.

Oxygen deficiency around the time of birth (perinatal hypoxia).

Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS).

Trauma to the head affecting the auditory system.

Exposure to ototoxic medications – drugs known to damage hearing, like aminoglycoside antibiotics or loop diuretics.

Congenital SNHL Etiologies: The most frequent prenatal or congenital cause of SNHL is infection acquired in the womb (intrauterine infection). A key group of such infections is known as TORCHES:

Toxoplasmosis

Other agents (such as syphilis)

Rubella (German measles)

Cytomegalovirus (CMV)

Herpes simplex virus

Etc. (representing other less common congenital infections).

Note on Terminology: The term “Sensorineural” itself emphasizes that the hearing loss involves both the sensory cells (hair cells in the cochlea) and the neural pathways (auditory nerve) of the auditory system.

Mixed Hearing Loss:

Combined Nature: Mixed hearing loss is defined by the co-occurrence of both conductive and sensorineural hearing loss in the same ear.

Dual Pathology: This type of hearing loss signifies that there are problems present in both the sound conduction pathway (outer or middle ear) and the sensory/neural pathway (inner ear or auditory nerve).

Example Development: Mixed hearing loss can occur in an individual who already has a pre-existing sensorineural hearing loss and subsequently develops a conductive component, such as experiencing a middle ear infection on top of their pre-existing SNHL.

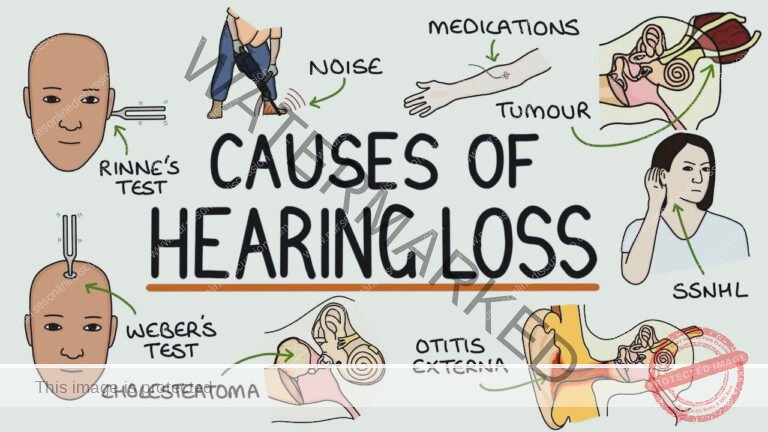

Causes of Hearing Impairment

Hearing impairment can arise from a wide range of factors that affect different parts of the auditory system. Key causes are detailed below:

Ear Infections: Infections of the ear, notably otitis media (middle ear infection), are a significant cause of hearing problems. These infections trigger:

Inflammation within the middle ear space.

Accumulation of fluid behind the eardrum.

This fluid and inflammation can hinder the efficient transmission of sound vibrations to the inner ear, leading to hearing loss, typically conductive in nature.

Ear Canal Blockages: Physical obstructions in the ear canal can impede sound entry and cause hearing impairment. These blockages may be due to:

Foreign objects lodged in the canal.

Impacted earwax (cerumen), creating a plug.

Fluid buildup in the ear canal, often associated with colds or allergies and subsequent swelling.

These blockages physically prevent sound waves from reaching the middle and inner ear effectively.

Damage to Eardrum and Middle Ear Bones: Injury or damage to the delicate structures of the middle ear can disrupt sound conduction and cause hearing loss. This includes:

Tears or perforations in the tympanic membrane (eardrum).

Damage to the tiny ossicles (malleus, incus, stapes) – the small bones in the middle ear that transmit sound vibrations.

Such damage interferes with the efficient transfer of sound vibrations from the eardrum to the inner ear.

Genetic Predisposition (Genetic Disorders): Certain genetic disorders, inherited from parents or arising from new mutations, can affect hearing. These genetic factors may:

Disrupt the normal development of the inner ear structures responsible for sound sensing (cochlea).

Interfere with the development or function of the auditory nerve, which carries signals to the brain.

These genetic abnormalities can result in varying degrees of hearing impairment, often sensorineural in type.

Pregnancy Complications: Certain health issues or exposures during pregnancy can negatively impact the developing fetus’s auditory system, leading to hearing impairment present at birth (congenital). These include:

TORCHES Infections: Infections acquired by the mother during pregnancy that can cross the placenta and affect the fetus. TORCHES is an acronym for a group of infections:

Toxoplasmosis

Other infections (like Syphilis)

Rubella (German Measles)

Cytomegalovirus (CMV)

Herpes Simplex

Etc.

Exposure to certain chemotherapy drugs during pregnancy, some of which are known to be ototoxic (harmful to hearing).

Perinatal Problems Related to Alcohol: Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASD), resulting from maternal alcohol consumption during pregnancy, are linked to a high incidence of hearing loss in offspring, reported in up to 64% of infants born to mothers with alcohol use disorders. This hearing loss can be attributed to:

The direct ototoxic effect of alcohol on the developing fetal auditory system.

Malnutrition during pregnancy often associated with alcohol abuse, further compromising fetal development.

Premature Birth: Premature birth is a significant risk factor for sensorineural hearing loss in infants. Prematurity increases the risk of hearing loss due to several factors associated with premature delivery and neonatal intensive care, including:

Increased susceptibility to hypoxia (oxygen deprivation) around the time of birth.

Higher likelihood of developing hyperbilirubinemia (severe jaundice).

Necessity of ototoxic medications (like aminoglycoside antibiotics) for treating infections in premature infants.

Exposure to high noise levels in neonatal intensive care units (NICUs), which can damage the delicate hearing of premature babies.

The risk of hearing loss is notably higher in infants with very low birth weight ( less than 1500 grams at birth).

Exposure to Sudden Loud Noise: Exposure to excessively loud sounds, either sudden or prolonged, is a major cause of acquired hearing loss. Over time, loud noise can cause damage to the delicate hair cells within the cochlea. These hair cells are essential for converting sound vibrations into electrical signals sent to the brain. Damage to these hair cells, often irreversible, leads to sensorineural hearing loss. Examples of noise exposure risks include:

Working in noisy industrial environments without adequate hearing protection.

Attending loud concerts or music events without using ear protection.

Traumatic Head Injury: Head injuries, ranging from mild to severe, can result in hearing impairment. Head trauma can damage:

The auditory nerve itself, disrupting signal transmission.

The delicate structures of the ear, particularly the inner ear, through fractures of the temporal bone or other mechanisms.

The brain’s auditory processing centers, if the injury affects brain regions responsible for hearing interpretation.

This damage can lead to varying degrees of hearing loss, which can be either temporary or permanent depending on the nature and severity of the head injury.

Certain Medical Disorders: Various medical conditions and diseases can have hearing loss as a symptom or complication:

Stroke: Strokes, which disrupt blood supply to the brain, can cause hearing loss if they affect brain regions involved in auditory processing. The specific type and extent of hearing loss depend on the location and severity of the stroke and which blood vessels are affected in the brain.

Multiple Sclerosis (MS): Multiple sclerosis is an autoimmune disease where the body’s immune system mistakenly attacks the protective myelin sheath covering nerve fibers in the central nervous system. If MS affects the auditory nerve, it can lead to hearing loss, potentially progressing to complete deafness in one or both ears due to nerve damage.

Perilymph Fistula: A perilymph fistula is a small tear or rupture in the thin membranes of the round or oval window of the cochlea. These windows are openings between the middle and inner ear. When a fistula occurs, perilymph fluid leaks from the inner ear into the middle ear. Perilymph fistulas are typically caused by:

Physical trauma to the head or ear.

Barotrauma, such as from rapid changes in air pressure (e.g., during scuba diving or air travel).

They often present with a combination of vertigo (spinning sensation) and hearing loss, typically conductive or mixed in nature.

Infections: Infections, both viral and bacterial, can damage the auditory system:

Viral Infections: Viral infections of the inner ear (labyrinthitis) can specifically target and damage the cochlea or vestibular nerve, leading to sensorineural hearing loss, vertigo, and balance problems.

Childhood Viral Illnesses: Certain childhood viral illnesses, although now less common due to vaccination, can cause deafness as a complication. These include:

Measles

Mumps

Rubella (Congenital Rubella Syndrome)

Herpes Viruses: Cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection, a type of herpesvirus, is a significant cause of congenital hearing loss in newborns when contracted by the mother during pregnancy. CMV can also lead to progressive sensorineural hearing loss in children as they grow.

Meningitis: Meningitis, especially bacterial meningitis, is a major cause of acquired sensorineural hearing loss, particularly in children. The infection can directly damage the cochlea or auditory nerve, or indirectly cause hearing loss through inflammation and toxic effects.

Inherited Conditions: Several inherited genetic conditions have hearing loss as a characteristic feature:

Down Syndrome (Trisomy 21): Individuals with Down syndrome have a higher predisposition to hearing loss, often due to:

Increased incidence of middle ear effusions and conductive hearing loss, particularly in childhood.

Increased risk of developing high-frequency sensorineural hearing loss as they age.

Otosclerosis: Otosclerosis is a hereditary condition that causes abnormal bone remodeling in the middle ear. It leads to fixation of the stapes bone, preventing its normal vibration and causing conductive hearing loss.

Vestibular Schwannoma (Acoustic Neuroma): A vestibular schwannoma (also called an acoustic neuroma) is a benign tumor that grows on the vestibulocochlear nerve (8th cranial nerve), which carries hearing and balance signals from the inner ear to the brain. As it grows, the tumor can compress the vestibulocochlear nerve, leading to:

Progressive sensorineural hearing loss.

Tinnitus (ringing in the ear).

Balance problems and vertigo.

Congenital Structural Problems: Certain structural abnormalities present at birth can cause hearing loss:

Superior Semicircular Canal Dehiscence (SSCD): Superior semicircular canal dehiscence is a rare condition where there is an abnormal gap or thinning in the bone overlying the superior semicircular canal in the inner ear. This dehiscence can create a “third window” into the inner ear, altering pressure dynamics and leading to:

Low-frequency conductive hearing loss: Primarily affecting the ability to hear lower-pitched sounds.

Autophony: An unusual phenomenon where individuals hear their own internal sounds (like their voice or heartbeat) excessively loudly in the affected ear.

Vertigo: Dizziness or imbalance, often triggered by loud sounds or changes in pressure.

Medications (Ototoxicity): Certain medications are known to be ototoxic, meaning they have the potential to damage the inner ear and cause hearing loss or tinnitus as a side effect. Examples of ototoxic medications include:

Loop Diuretics: Such as furosemide (Lasix) and bumetanide (Bumex), commonly used to treat fluid retention and hypertension.

Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs): High doses or prolonged use of NSAIDs, such as aspirin or ibuprofen, can, in some cases, cause temporary or, rarely, permanent hearing loss or tinnitus.

Aminoglycoside Antibiotics: Aminoglycosides, a class of potent antibiotics like gentamicin, tobramycin, and streptomycin, are well-known ototoxic agents. They can cause both hearing loss and balance problems, and their use requires careful monitoring, especially in vulnerable individuals.

Environmental Chemicals (Ototoxins): Exposure to certain environmental toxins can also damage hearing:

Metals: Heavy metals like lead are ototoxic and can contribute to hearing loss, particularly with chronic exposure.

Solvents: Certain industrial solvents, such as toluene, are also ototoxic and can cause irreversible sensorineural hearing loss, especially affecting high-frequency hearing. Chronic exposure to these toxins can damage the delicate hair cells in the cochlea and auditory pathways.

Physical Trauma (Head Injuries): As mentioned previously in point 9, head injuries can cause hearing loss. Beyond direct damage to the ear structures, head trauma can also damage:

Brain centers responsible for processing auditory information.

This damage can lead to temporary or permanent hearing loss, as well as tinnitus (ringing in the ears) in some cases.

Sensorineural Hearing Impairment (Further Elaboration on SNHL Causes): This category broadly encompasses causes that directly affect the inner ear or neural pathways:

Genetic Disorders: As mentioned in point 4, various inherited genetic disorders can disrupt the development or function of the inner ear and/or auditory nerve, leading to congenital or progressive sensorineural hearing loss.

Ear or Head Injuries: Skull fractures that directly involve the temporal bone or trauma to the inner ear structures are common causes of SNHL, as discussed in point 9 and 16.

Complications During Pregnancy or Birth: As detailed in points 5 and 7, complications during pregnancy (TORCHES infections) and birth (prematurity, hypoxia) are significant risk factors for sensorineural hearing loss in newborns and infants, often due to damage to the developing auditory system.

Infections or Illnesses: Certain infections and illnesses beyond meningitis and labyrinthitis (discussed in point 11) can damage inner ear structures and cause SNHL. These include:

Repeated or chronic middle ear infections (otitis media), especially if complications arise or the inner ear becomes involved.

Childhood viral illnesses like mumps, measles, and chickenpox, although less common now due to vaccination, can still cause SNHL in rare cases.

Brain tumors, particularly those affecting the cerebellopontine angle (where the vestibulocochlear nerve is located), can compress or damage the auditory nerve, leading to SNHL.

Medications (Ototoxic Drugs): As detailed in point 14, certain medications with ototoxic properties can cause sensorineural hearing loss as a side effect.

Loud Noise Exposure: Chronic or repeated exposure to loud noise over time, as described in point 8, is a leading cause of acquired sensorineural hearing loss, often termed noise-induced hearing loss (NIHL). Loud noise damages the delicate hair cells in the cochlea, leading to permanent SNHL over time.

Signs, Symptoms, and Related Issues of Hearing Loss

Hearing loss can manifest in a range of primary, sensory, and secondary symptoms. It can also be associated with various related conditions that impact overall well-being.

Primary Symptoms of Hearing Loss

These are the most direct and noticeable difficulties individuals with hearing impairment experience:

Difficulty in Speech Comprehension:

Struggling to follow conversations, particularly when there is background noise or multiple speakers.

Especially challenged in understanding the voices of children and women, which tend to have higher frequencies often affected by hearing loss.

Frequently needing to ask others to repeat statements or information.

Reduced Sound Volume Perception:

Perceiving sounds and speech as faint, indistinct, or lacking clarity.

A sense that sounds are muffled or attenuated, as if the volume has been turned down.

The increasing need to turn up the volume on electronic devices such as televisions, radios, music players, and other audio equipment to hear adequately.

Telephone Communication Challenges:

Experiencing difficulties hearing clearly during phone conversations.

Necessity of using speakerphone or headphones to improve phone audibility.

Sound Localization Difficulties:

Impaired ability to pinpoint the direction or source of sounds.

Feeling disoriented or confused in noisy or complex sound environments, due to inability to localize sounds effectively.

Speech Discrimination Issues in Noise (“Cocktail Party Effect”):

Experiencing significant trouble understanding speech when there is competing background noise.

Having particular difficulty following conversations in crowded settings or places with ambient noise, such as restaurants or social gatherings.

Sensory Symptoms Related to Hearing Loss

These symptoms are more sensory in nature and can accompany hearing impairment:

Ear Pain or Pressure: Experiencing discomfort, pain, or a sensation of pressure localized within the ears.

Blocked Ear Sensation: A persistent feeling of ear blockage or fullness in the ear, even when there is no physical obstruction present.

Secondary Symptoms of Hearing Loss

These symptoms are often indirect consequences or associated problems arising from hearing loss:

Tinnitus: The perception of sound in the ears or head when no external sound source is present. This can manifest as:

Ringing

Buzzing

Hissing

Clicking

Other phantom sounds.

Vertigo and Disequilibrium: Experiencing vestibular symptoms due to inner ear involvement, such as:

Dizziness or lightheadedness.

Vertigo – a sensation of spinning or whirling.

Disequilibrium – unsteadiness or imbalance.

Tympanophonia: An abnormal and often uncomfortable sensation of hearing one’s own internal sounds, particularly:

One’s own voice sounding excessively loud or echoing.

Exaggerated perception of respiratory sounds (breathing).

This symptom is typically associated with specific conditions affecting the middle or inner ear pressure balance, such as a patulous Eustachian tube (abnormally open Eustachian tube) or superior semicircular canal dehiscence (SSCD).

Facial Movement Disturbances: Changes or abnormalities in facial movements can, in some instances, be a related symptom, potentially indicating a more serious underlying condition affecting cranial nerves, such as:

Possible presence of a tumor affecting the vestibulocochlear nerve (acoustic neuroma).

Neurological events like a stroke impacting brain regions controlling facial nerves and hearing.

Other Associated Conditions Linked to Hearing Loss

Hearing loss, particularly if untreated, can be linked to or exacerbate other health issues:

Headaches: Headaches may occur in association with hearing loss, especially in cases involving:

Ear pain or pressure.

Tension-type headaches related to the strain of listening.

Emotional Distress: Hearing loss can contribute to significant emotional and psychological distress, potentially leading to:

Social isolation and withdrawal from social activities due to communication difficulties.

Frustration, irritability, and feelings of inadequacy.

Increased risk of developing depression or anxiety disorders.

Cognitive Decline: Emerging research suggests a potential link between hearing loss and accelerated cognitive decline. Studies indicate a correlation between untreated hearing loss and:

Increased risk of cognitive impairment and memory problems.

Higher likelihood of developing dementia in older adults, possibly due to social isolation and reduced cognitive stimulation.

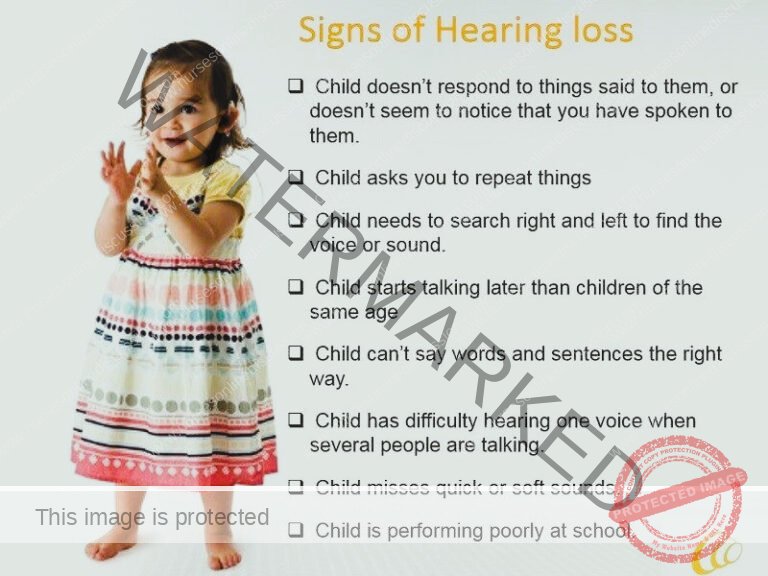

Hearing Loss Manifestations Across Age Groups

Hearing loss can present differently depending on the age of the affected individual. Key indicators to watch for include:

Infants (0-12 months):

Lack of Response to Environmental Sounds: Infant only startles or awakens in response to physical touch, rather than reacting to typical environmental noises in their surroundings.

No Startle Reflex to Loud Noises: Absence of a startle response even to sudden, loud noises.

No Head Turn to Sound Source (by 4 months): Infant does not consistently turn their head towards the direction of sounds by 4 months of age, indicating a potential auditory processing issue.

Absence of Babbling (by 6 months): Infant does not begin to babble or produce pre-speech sounds by 6 months of age, which is a critical milestone in auditory and speech development.

Delayed Speech Development: Child’s speech development is not progressing as expected or is significantly delayed compared to typical developmental milestones.

Young Children (1-5 years):

No Spoken Language (by 2 years): Child does not begin to speak or use meaningful words by 2 years of age, indicating a significant speech delay which may be linked to hearing loss.

Communication Primarily Through Gestures: Child primarily relies on gestures rather than spoken language to communicate needs and wants.

Unclear Speech (Age Inappropriate): Child’s speech is not easily understandable or is less distinct than expected for their age, suggesting potential underlying hearing or speech processing issues.

Developmental Delays: Displays delays in other areas of development, particularly cognitive or language-related skills, potentially linked to auditory deprivation.

Solitary Play Preference: Prefers to engage in solitary play activities rather than interacting with peers or participating in group activities, possibly due to communication barriers.

Immature Emotional Behavior: Exhibits emotional behavior that seems younger than their chronological age, potentially linked to communication frustration and social challenges.

Lack of Response to Common Sounds: Does not consistently respond to everyday auditory cues such as the ringing of a telephone or a doorbell, even when the sound is audible to others.

Lip Reading Tendency: Child frequently focuses intently on facial expressions and lip movements when someone is speaking, indicating reliance on visual cues to supplement or compensate for reduced auditory input.

Older Children (6-12 years):

Frequent Requests for Repetition: Child often asks others to repeat statements or instructions, indicating difficulty hearing or understanding initial communication.

Inattentiveness or Daydreaming: Appears inattentive in class or frequently seems to be daydreaming, which may be misattributed to attention deficits when the underlying cause is hearing difficulty.

Poor Academic Performance: Experiences unexplained difficulties in school or academic performance declines, potentially due to communication and learning challenges related to hearing loss.

Abnormal Speech Patterns: Displays monotone speech or other abnormal speech characteristics, possibly due to impaired auditory feedback and monitoring of their own voice.

Inappropriate Responses Without Visual Cues: Gives answers that are inappropriate or off-topic in conversations unless they are able to directly see the speaker’s face and rely on visual cues for communication, highlighting reliance on lip-reading.

Classification/Grading of Hearing Loss

Hearing impairment is classified based on different factors, primarily by its nature (type) and extent (severity). Additionally, hearing loss can affect one ear (unilateral) or both ears (bilateral). It can also be described by its duration (temporary or permanent) and onset (sudden or progressive).

Typical Hearing Range (Normal Hearing):

Individuals with normal hearing have hearing thresholds that fall within the expected range for auditory perception, generally considered to be up to 25 decibels (dB).

Mild Hearing Loss (Slight Impairment):

Hearing Threshold Range: Individuals in this category exhibit hearing thresholds between 26 and 40 dB.

Functional Impact: Persons with mild hearing loss may experience challenges primarily in perceiving faint or distant sounds, such as whispers or soft speech from a distance.

Moderate Hearing Loss:

Hearing Threshold Range: Hearing thresholds in this category range from 41 to 60 dB.

Functional Impact: Individuals with moderate hearing loss typically encounter difficulties in understanding conversational speech, especially in environments with background noise or competing sounds that mask speech signals.

Severe Hearing Loss:

Hearing Threshold Range: Hearing thresholds for severe hearing loss fall between 61 and 80 dB.

Functional Impact: Individuals with severe hearing loss often rely heavily on amplification technologies, like hearing aids, to facilitate communication. Even with hearing aids, they may still have significant difficulty understanding speech and require additional communication strategies.

Profound Hearing Loss:

Hearing Threshold Range: Hearing thresholds are very significantly elevated, measured at 81 dB or greater.

Functional Impact: Individuals with profound hearing loss have extremely limited or negligible functional hearing. They derive minimal benefit from conventional hearing aids and often communicate and perceive sound most effectively through alternative means such as cochlear implants or other assistive devices designed for profound deafness.

Diagnosis and Investigations of Hearing Impairment

Diagnosing hearing impairment involves a comprehensive evaluation utilizing several methods:

Patient History:

Case History (Anamnesis): Taking a detailed case history is crucial. Hearing loss diagnosis can be particularly challenging in infants and very young children because of their pre-verbal stage.

Parental Interview: However, healthcare providers can gather essential information from parents or caregivers by inquiring about:

Prenatal history (events during pregnancy).

Delivery history (details of the birth process).

Any birth-related injuries that might be relevant to hearing.

Medical History (Adults and Older Children): For older children and adults, a detailed medical history is essential. Healthcare professionals will ask questions to understand:

The onset and progression of hearing symptoms.

Whether hearing loss is in one ear (unilateral) or both ears (bilateral).

Any history of exposure to loud noises.

Current and past medications being taken.

Presence of a family history of hearing loss or related conditions.

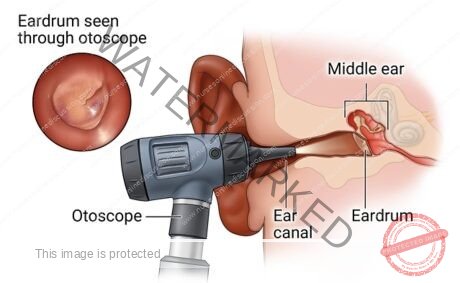

Physical Ear Examination:

Otoscopy: An otolaryngologist, commonly known as an ENT (Ear, Nose, and Throat) doctor, typically conducts a physical ear examination. This involves using an otoscope, a handheld instrument equipped with a light source and magnifying lens, to visually inspect:

The ear canal for obstructions or abnormalities.

The eardrum (tympanic membrane) for signs of:

Structural damage like perforations or scarring.

Earwax buildup potentially causing conductive hearing loss.

Presence of foreign bodies or other substances obstructing the ear canal.

Tympanometry: This diagnostic test assesses the function of the middle ear by:

Measuring the movement and flexibility of the eardrum.

Analyzing how the eardrum responds to variations in air pressure applied to the ear canal.

Providing valuable insights into middle ear conditions such as fluid buildup, eardrum perforation, or ossicular chain dysfunction.

Differential Tuning Fork Tests: A series of specialized hearing tests using a low-frequency tuning fork may be employed. These tests, including Weber, Rinne, Bing, and Schwabach tests, help to:

Evaluate auditory function and sound conduction.

Differentiate between various types of hearing loss.

Determine if hearing loss is unilateral (one ear) or bilateral (both ears).

Distinguish between conductive hearing loss (outer/middle ear problem) and other types of hearing loss.

Tuning Fork Tests (General): Tuning fork tests in general are useful bedside assessments to help:

Identify the likely cause of hearing loss.

Distinguish between conductive and sensorineural hearing loss types.

Procedure: A vibrating tuning fork is placed against different anatomical locations:

Various points on the face and skull.

Near and on the ears themselves.

The patient’s perception of sound loudness at each location helps determine the type of hearing loss.

Audiometry (Formal Hearing Testing): Audiometry is a detailed and objective measurement of a person’s hearing sensitivity across different frequencies and sound intensities. This comprehensive test helps to:

Precisely determine the degree of hearing loss: quantifying how mild to profound the loss is.

Establish the configuration of hearing loss: identifying which frequencies (pitches) are most affected, often visualized on an audiogram.

Pure Tone Audiometry: The most frequently used type of audiometry, particularly for individuals older than 5 years of age who can reliably participate in the testing procedure.

Procedure: The test involves presenting pure tones (single-frequency sounds) at varying frequencies (pitches) and intensities (volumes) to each ear individually using headphones or insert earphones.

Patient Response: The patient is instructed to indicate (e.g., by raising a hand or pressing a button) when they just barely hear the presented sound.

Audiogram Plotting: The results are meticulously plotted on an audiogram, a graph that visually represents hearing thresholds at different frequencies, allowing for a detailed analysis of hearing sensitivity.

Visual Reinforcement Audiometry (VRA): This specialized audiometry technique is designed for assessing hearing in younger children, typically infants and toddlers, who may not be able to follow complex instructions required for pure tone audiometry.

Stimulus Reinforcement: VRA utilizes visual stimuli to encourage and reinforce a child’s responses to sounds. These visual reinforcements might include:

Engaging toys that light up or move when a sound is presented.

Visually appealing lights or animated displays.

Behavioral Observation: The child’s behavioral responses to sound presentations, such as head turns or eye movements towards the visual reinforcer, are observed and recorded to determine hearing thresholds.

Laboratory Testing (Selective Cases): Laboratory tests are generally not routine for hearing loss diagnosis but may be indicated in specific circumstances:

Suspected Infection or Inflammation: When an infection or inflammatory condition is suspected as the underlying cause of hearing loss, blood samples or other body fluids may be collected and submitted for:

Microbiological culture to identify infectious agents.

Inflammatory markers to assess the degree of inflammation.

Specific serological tests to detect antibodies to certain infections.

Specialized Hearing Tests: Beyond pure tone audiometry, other specialized hearing tests can provide more specific diagnostic information:

Speech-in-Noise Test: This test evaluates a person’s ability to understand speech in the presence of background noise. It simulates real-world listening situations and is helpful in assessing:

Functional hearing ability in everyday, challenging listening environments.

Difficulties with speech discrimination in noise, which is a common complaint in certain types of hearing loss.

Otoacoustic Emissions (OAE) Test: OAE testing is an objective hearing test that does not require active patient participation, making it particularly useful for:

Toddlers and young children who may not be able to cooperate reliably with behavioral hearing tests.

Infant hearing screening programs.

Also valuable for assessing hearing function in older children and adults.

Mechanism: OAE test measures otoacoustic emissions, which are faint sounds produced by the healthy outer hair cells in the cochlea in response to sound stimulation.

Interpretation: The presence or absence of OAEs can provide information about the function of the inner ear and specifically the outer hair cells. Absent or reduced OAEs can indicate certain types of hearing loss, particularly sensorineural hearing loss involving outer hair cell dysfunction.

Advanced Imaging Scans (Selective Cases): Advanced imaging techniques are typically reserved for selected cases when further investigation is needed to visualize ear structures or identify underlying pathology:

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) and Computed Tomography (CT) Scans: MRI and CT scans are powerful imaging modalities that may be used to:

Identify structural pathologies that could be causing hearing loss.

Visualize the anatomy of the ear and surrounding structures in detail.

Detect conditions such as:

Tumors affecting the auditory nerve (e.g., vestibular schwannoma).

Inner ear malformations.

Temporal bone fractures resulting from trauma.

Other structural abnormalities.

These scans are typically used in selected cases where there is clinical suspicion of a specific underlying condition requiring further anatomical investigation.

Auditory Brainstem Response (ABR) Test: The Auditory Brainstem Response (ABR) test is an objective neurophysiologic test that:

Measures the electrical activity generated by the auditory nerve and brainstem in response to sound stimulation.

Often used for infants and young children who cannot undergo conventional behavioral hearing tests due to age or developmental stage.

Provides valuable information about the integrity of the auditory pathway from the inner ear to the brainstem, helping to:

Identify neurological hearing loss or auditory neuropathy.

Estimate hearing thresholds in individuals unable to participate in subjective testing

Management of Hearing Impairment

The approach to treating hearing loss is highly personalized, varying significantly based on the origin, category, and intensity of the auditory deficit.

1. Determining the Origin:

Age-related or Noise-Induced Hearing Loss: These are frequently encountered origins of auditory impairment, often developing gradually and proving to be permanent. Intervention primarily centers on mitigating the impact through the use of supportive technologies.

Specific Medical Conditions: In certain instances, surgical procedures can be effective in addressing particular types of hearing deficits.

2. Treatment Approaches:

a) Supportive Technology:

Hearing Amplification Devices: These devices function to boost auditory input, enhancing both hearing sensitivity and speech clarity. Audiology professionals customize and calibrate these devices to ensure optimal user benefit. For significant sensorineural hearing loss, implementation of hearing aids may be necessary even in infants as young as three months.

Specialized Listening Systems: These are designed to improve auditory perception in specific scenarios, for example, facilitating communication via telephone (text-based phones) , enhancing television viewing, or improving comprehension in group discussions.

b) Surgical Procedures:

Ventilation Tubes (Tympanostomy): For cases of mild to moderate conductive hearing loss, a treatment strategy involves inserting tympanostomy tubes. These tubes maintain air circulation within the middle ear space.

Tympanic Membrane Reconstruction (Tympanoplasty): This surgical repair aims to reconstruct the eardrum and/or the small bones of the middle ear (ossicles) when a perforation is present.

Superior Semicircular Canal Dehiscence Repair: Corrective surgery for a bony defect over the superior semicircular canal of the inner ear can resolve certain types of hearing issues along with self-hearing of one’s own voice (autophony) and balance disturbances (vertigo).

Eardrum Incision with Tube Insertion (Myringotomy & Ventilation Tubes): Creating a small incision in the eardrum (myringotomy) followed by the placement of ventilation tubes can effectively manage ear infections and the accumulation of fluid in the middle ear.

Acoustic Neuroma Management (Vestibular Schwannoma): Treatment options for these tumors include radiation therapy or surgical removal. However, preserving hearing function is often a complex challenge in these cases.

Stapes Surgery (Stapedectomy/Stapedotomy): Replacing or reshaping the stapes bone, one of the ossicles in the middle ear, can restore auditory function in conductive hearing loss caused by otosclerosis.

c) Addressing Root Causes:

Earwax Removal: Simple removal of accumulated earwax can resolve hearing reduction in some instances.

Infection Management: Prompt and effective treatment of ear infections is critical to prevent further auditory system damage.

Structural Correction: Surgical intervention might be required to repair physical damage to the eardrum or the ossicles.

d) Cochlear Implantation:

For profound hearing loss, a cochlear implant offers a solution by bypassing the damaged components of the inner ear. It directly stimulates the auditory nerve, enabling the perception of sound.

Cochlear implantation is a surgical option for managing hearing loss in children. Bilateral cochlear implants can be considered for infants from 12 months old with severe bilateral hearing loss, and potentially earlier if hearing loss results from meningitis (to circumvent middle ear damage). For children with congenital deafness and no prior auditory input, implantation before age 6 is crucial for auditory cortex development for sound awareness and speech acquisition. For children unsuitable for cochlear implants, sign language and specialized deaf education programs should be considered.

3. Preventative Measures:

Noise-Induced Hearing Loss Prevention: Minimizing exposure to high-intensity sounds, consistently using hearing protection in noisy environments, and adhering to safe noise level recommendations are vital preventive actions.

Congenital Hearing Loss Prevention: Vaccinations against diseases like rubella, Haemophilus influenzae, and Streptococcus pneumoniae can lower the occurrence of preventable causes of congenital hearing loss.

Regular Hearing Assessments: Routine hearing examinations are important for the early detection of hearing loss indicators, facilitating timely intervention.

4. Adapting to Life with Hearing Loss:

Communication Strategies: Learning sign language, utilizing assistive devices, and employing clear and effective communication techniques are beneficial for navigating daily life.

Support Networks: Connecting with peer support groups provides valuable emotional support and practical coping strategies from individuals with shared experiences.

We are a supportive platform dedicated to empowering student nurses and midwives through quality educational resources, career guidance, and a vibrant community. Join us to connect, learn, and grow in your healthcare journey

Quick Links

Our Courses

Legal / Policies

Get in Touch

(+256) 790 036 252

(+256) 748 324 644

Info@nursesonlinediscussion.com

Kampala ,Uganda

© 2025 Nurses online discussion. All Rights Reserved | Design & Developed by Opensigma