Manage of Women with Gynaecological Conditions

Subtopic:

Fibroids

(FIBROMYOMAS)

Fibroids are non-cancerous growths that develop from the muscular wall of the uterus, specifically originating in the myometrium, which is the smooth muscle layer. They are considered benign tumors, meaning they are not malignant and do not spread to other parts of the body.

Other common names are: uterine leiomyoma, myoma, fibromyoma, fibroleiomyoma.

(Leiomyoma specifically refers to a benign tumor of smooth muscle tissue.)

Fibroids are most frequently diagnosed in women after the age of 30, and they are observed more often in women who have not yet had children. While they can occur anywhere in the uterus, they are more commonly found within the main body of the uterus rather than in the cervix region. These growths are composed of both muscle cells and fibrous connective tissue. Fibroids can vary significantly in number, from a solitary growth to multiple tumors, and their size can range dramatically from microscopic to very large masses.

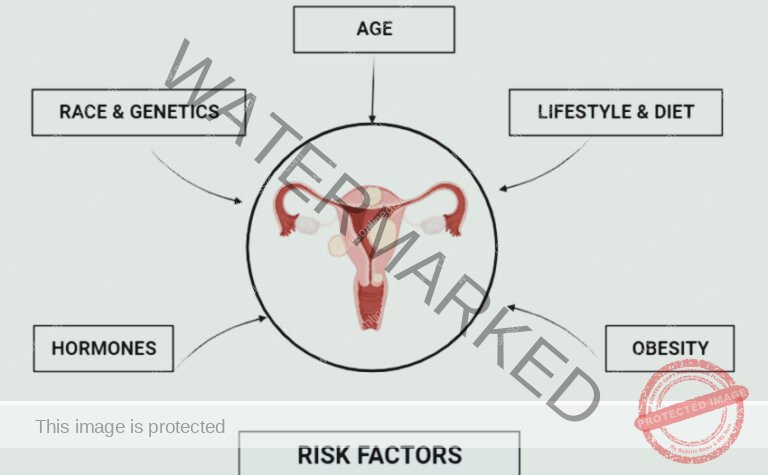

Risk factors for uterine fibroids

Age: The occurrence of uterine fibroids becomes more frequent as women approach their 30s and 40s. This age range marks a period of increased susceptibility.

Parity: Women who have not experienced childbirth (nulliparous) or those with a limited number of pregnancies (low parity) face a greater chance of developing fibroids compared to women with multiple pregnancies.

Race/Ethnicity: There is a recognized disparity in fibroid prevalence across racial groups. Women of African ancestry (Black or of African descent) are observed to have a higher incidence of uterine fibroids when compared to women of Caucasian ancestry (White).

Family History: A predisposition to fibroids can be inherited. Women with a family history of fibroids, particularly in first-degree relatives such as mothers or sisters, have an elevated personal risk.

Hyper-estrogenemia: Elevated levels of estrogen in the body can act as a growth-promoting factor for fibroids. Higher estrogen levels can stimulate the development and enlargement of these tumors.

Obesity: Excess body weight and obesity are linked to an increased risk of uterine fibroids. Adipose tissue can produce estrogen, potentially contributing to fibroid development.

Early Onset of Menarche: Women who experienced their first menstrual period at an early age may have a slightly increased risk of developing fibroids later in life. Earlier exposure to cyclical hormonal changes may play a role.

Low Level of Vitamin D: Research suggests a possible link between insufficient levels of Vitamin D in the body and a higher likelihood of developing uterine fibroids. Vitamin D might have a role in regulating uterine tissue growth.

Medications (Estrogen Replacement Therapy): Prolonged use of estrogen-based hormone replacement therapy, especially if it is not balanced with progesterone, can increase the risk of uterine fibroids. Exogenous estrogen can stimulate fibroid growth in susceptible individuals.

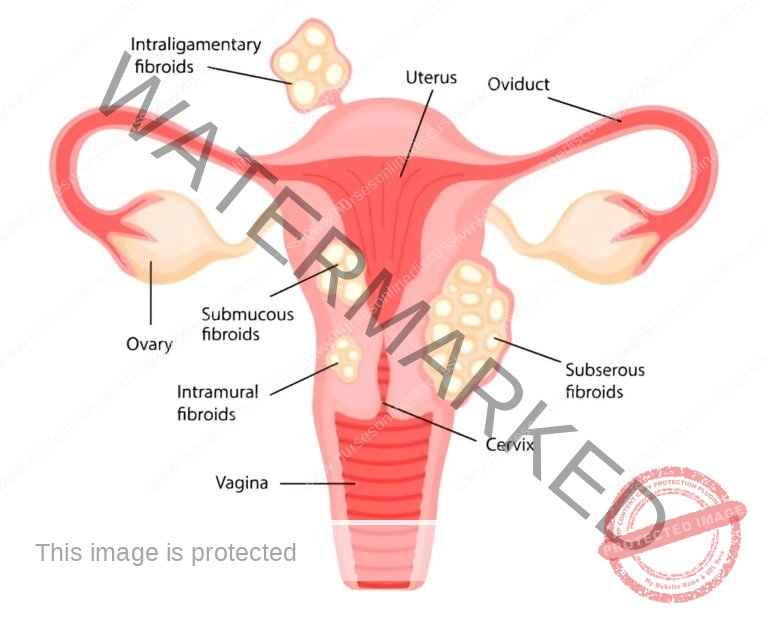

Classes or Types of Uterine Fibroids

Submucosal Fibroids: These fibroids develop just beneath the endometrium, which is the inner lining of the uterus, and protrude into the uterine cavity. (Endometrium is the tissue lining the uterus.) Their location often leads to symptoms such as heavy menstrual bleeding (menorrhagia) and can be a factor in infertility.

Intramural Fibroids (Interstitial): Representing the most prevalent type, intramural fibroids are embedded within the myometrium, the muscular wall of the uterus. (Myometrium is the muscular middle layer of the uterus.) As they grow, they can distort the uterus’s shape, potentially causing pain, a feeling of pelvic pressure, and other related symptoms.

Subserosal Fibroids: These fibroids originate on the outer surface of the uterus, underneath the serosa, the outer layer. They project outwards, sometimes becoming quite large and extending away from the uterus. Subserosal fibroids are known to cause pelvic discomfort and create pressure on adjacent pelvic organs.

Cervical Fibroids: These fibroids are a less common type, developing in the cervix, which is the lower portion of the uterus connecting to the vagina. They can manifest with pain and discomfort, and in certain instances, may impact fertility or present challenges during childbirth.

Fibroids of the Broad Ligament: This rarer type of fibroid arises within the broad ligament, a supportive fold of peritoneum that helps to suspend and stabilize the uterus within the pelvic cavity. Management of broad ligament fibroids is often tailored to their specific size and location due to their unique anatomical position.

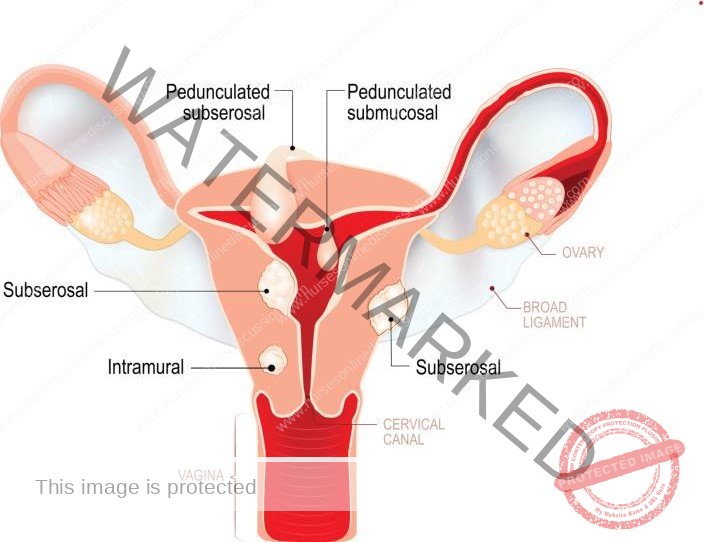

Location or Sites of Uterine Fibroids

The location of uterine fibroids can be further categorized based on their position within and around the uterus:

I. Subperitoneal: These fibroids develop beneath the peritoneal surface, meaning they are situated on the outer surface of the uterus, directly under the peritoneum, the membrane lining the abdominal cavity. They can extend outwards, leading to abdominal discomfort and pressure sensations. (Peritoneum is the membrane lining the abdominal cavity.)

II. Submucous: Growing inwards, submucous fibroids bulge or protrude into the uterine cavity, displacing the endometrium. This location is strongly associated with heavy and prolonged menstrual bleeding, irregular menstrual cycles, and potential issues with fertility.

III. Pedunculated Fibroids: These fibroids are distinguished by their attachment to the uterus via a stalk or pedicle. (Pedicle refers to a stem-like base.) This pedicle contains the fibroid’s blood supply. Pedunculated fibroids can be either subserosal, extending outwards from the uterus, or submucous, projecting into the uterine cavity, depending on their origin point.

IV. Intramural: The most frequently encountered location, intramural fibroids reside within the myometrium, the muscular wall of the uterus. Their growth can lead to uterine enlargement and associated symptoms such as pelvic pain and a feeling of pressure.

V. Subserosal: Situated at the outer border of the myometrium, subserosal fibroids grow outwards, located beneath the serosa, the outermost covering of the uterus. They can attain significant size and contribute to pelvic discomfort. (Serosa is the outermost layer of the uterus and other organs.)

VI. Cervical: As previously noted, cervical fibroids are specifically located within the cervix, the lower segment of the uterus that connects to the vagina. While less common, they can still cause symptoms similar to other fibroid types, including pain and pressure.

Changes (Degenerative) that can take place in the fibroid

Uterine fibroids can undergo various degenerative changes over time, or as a result of specific conditions. These alterations modify the tissue structure of the fibroid.

Red Degeneration: Frequently occurring during pregnancy, red degeneration is triggered by a compromised blood supply to the fibroid. This leads to necrosis, or tissue death, within the fibroid. The fibroid takes on a reddish appearance and softens in texture, described as “beefy” due to its color and consistency. (Necrosis is cell death in living tissue.)

Atrophy: Following menopause, the decline in hormone production, particularly estrogen, can cause fibroids to shrink, a process known as atrophy. This involves a reduction in size or wasting of the fibroid tissue as hormonal support diminishes.

Hyaline Degeneration: In hyaline degeneration, the fibroid tissue undergoes a transformation, becoming softer as the muscle fibers are gradually replaced by a homogenous, amorphous (structureless) material.

Parasitic Fibroid: This occurs when a pedunculated fibroid’s stalk (pedicle) undergoes torsion, or twisting, cutting off its original blood supply. To survive, the fibroid establishes a new blood supply by attaching itself to and drawing nourishment from surrounding pelvic tissues.

Cystic Change: Subsequent to hyaline degeneration, the fibroid tissue can further liquefy, accumulating fluid and developing a cystic appearance, resembling an ovarian cyst in structure.

Fatty Change: In fatty degeneration, the muscle cells within the fibroid are progressively replaced by fat tissue.

Calcification: Calcification involves the deposition of calcium salts within the fibroid tissue. This process leads to the fibroid becoming hardened, taking on a stone-like consistency.

Eggshell Fibroid (Calcification): A specific type of calcification where calcium deposits form a shell-like layer on the outer surface of the fibroid, while the interior retains its original tissue consistency.

Womb Stone: This term describes the end-stage of extensive calcification where the entire fibroid becomes thoroughly infiltrated and replaced by calcium salts, resulting in a complete hardening throughout the fibroid mass, resembling a stone.

Causes of Uterine Fibroids

The exact causes of uterine fibroids are not fully elucidated; however, current research strongly indicates that hormonal influences and genetic predisposition play key roles in their development.

Hormones: Estrogen and progesterone, the primary hormones regulating the menstrual cycle, are intimately linked to the growth dynamics of uterine fibroids. During each menstrual cycle, estrogen and progesterone stimulate the thickening of the endometrium, the uterine lining. These same hormones appear to promote fibroid growth. Consequently, fibroids often enlarge and become more prominent during a woman’s reproductive years when estrogen levels are highest. Conversely, as hormone levels decline significantly during menopause, fibroids tend to shrink and may become less symptomatic.

Genetics: Genetic factors are considered to contribute to fibroid development. Women with a family history of uterine fibroids, particularly among close relatives, demonstrate an increased risk. This suggests a potential heritable component, where specific genes might predispose individuals to fibroid formation.

Other Factors: While hormones and genetics are recognized as the primary influences, other elements may also contribute to fibroid development or progression. These include obesity, which is linked to altered hormone metabolism, racial background (with a higher incidence in women of African descent), and certain dietary patterns, although the exact mechanisms are still under investigation.

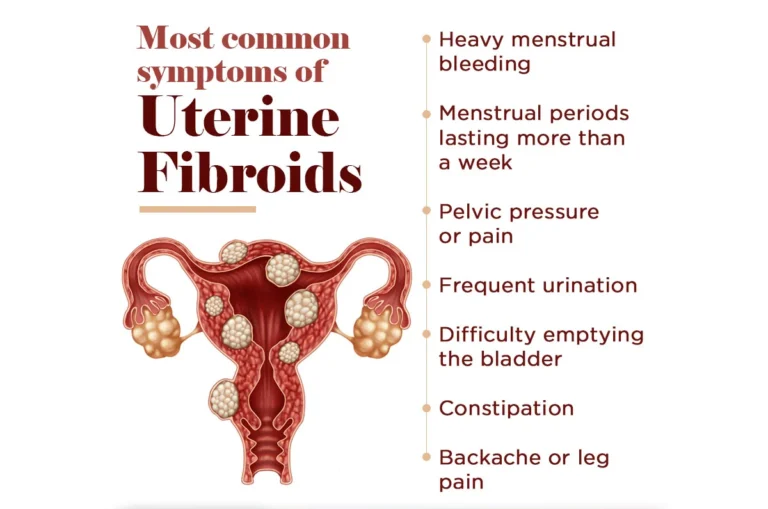

Clinical Presentation of Uterine Fibroids

Menstrual Disorders: Prolonged and Painful Periods: Fibroids are a common cause of alterations in menstrual patterns. They can lead to significantly heavier menstrual bleeding (medically known as menorrhagia), where periods are not only prolonged but also involve an increased volume of blood loss. Furthermore, many women experience increased menstrual pain (dysmenorrhea) which can range from mild discomfort to severe, debilitating cramps. This pain is thought to be exacerbated by uterine contractions attempting to expel clots or due to the fibroid’s physical presence and its effects on the uterine lining.

Postmenopausal Vaginal Bleeding: An Abnormal Sign: Vaginal bleeding that occurs after menopause is considered clinically significant and requires investigation. In women who have fibroids, the presence of postmenopausal bleeding, even if light, is an atypical symptom. It’s crucial to note that any bleeding after menopause is not normal and should be evaluated to rule out more serious conditions, though fibroids are among the potential benign causes.

Urinary and Bowel Dysfunction: Difficulty in Voiding and Constipation: Large fibroids, or those situated in certain locations, can exert pressure on adjacent organs. When fibroids press against the urinary bladder, it can lead to urinary frequency (needing to urinate more often) or urinary urgency (a sudden, compelling need to urinate). In some cases, it can also result in difficulty emptying the bladder completely (urinary retention). Similarly, if fibroids compress the rectum, they can impede bowel movements, leading to constipation and discomfort during defecation.

Pelvic Pressure and Discomfort: A common sensation experienced by women with fibroids is a feeling of pressure or heaviness localized in the pelvic region. This sensation can be persistent and may be described as a dragging or aching discomfort in the lower abdomen and pelvis. The sheer mass of the fibroids within the pelvis contributes to this feeling of weight and pressure.

Abdominal Distention and Fullness: When fibroids grow to a substantial size, or when multiple fibroids are present, they can cause a noticeable enlargement of the abdomen. This abdominal distention may be perceived as a general feeling of fullness, bloating, or an increase in abdominal girth. In some cases, the abdomen may visibly protrude, mimicking weight gain or pregnancy.

Referred Pain: Lower Back and Leg Pain: Fibroids can cause referred pain, meaning pain felt in areas distant from the actual fibroid location. Pressure from fibroids on pelvic nerves and surrounding structures can manifest as lower back pain, which may be chronic and aching in nature. Additionally, pain can radiate down the legs, sometimes described as sciatica-like pain, depending on nerve involvement and the fibroid’s position.

Dyspareunia: Painful Sexual Intercourse: Fibroids, particularly those located in the lower uterus or cervix, can cause pain or discomfort during sexual activity. This condition, known as dyspareunia, can result from the fibroids being directly compressed or from general pelvic congestion and sensitivity caused by their presence. The depth and intensity of pain can vary among individuals.

Subfertility and Infertility Concerns: Fibroids, depending on their size, number, and location within the uterus, can contribute to difficulties in conceiving or carrying a pregnancy to term. Submucosal fibroids, in particular, which distort the uterine cavity, can interfere with embryo implantation and increase the risk of miscarriage. Fibroids can also potentially affect sperm transport or create an unfavorable uterine environment for pregnancy.

Generalized Pressure-Related Symptoms: Beyond specific organ compression, fibroids can generate a range of pressure symptoms within the pelvis. As previously mentioned, bladder and bowel pressure are common. Furthermore, pressure on pelvic veins can impair venous return, potentially leading to the development of hemorrhoids (swollen veins in the rectum and anus) and varicose veins (enlarged, twisted veins, often in the legs) due to increased pressure and blood stasis in the pelvic and lower extremity venous systems.

Acute Degeneration: A Cause of Severe Pain: In certain situations, fibroids can undergo acute degeneration, often related to insufficient blood supply. This process involves rapid tissue breakdown within the fibroid, leading to the release of inflammatory mediators and causing significant, often sudden-onset, and severe pain. This pain is distinct from typical chronic pelvic discomfort and may require medical intervention for pain management.

Abdominal Enlargement: Visible Distention: Large uterine fibroids, or a significant number of smaller fibroids, can collectively cause a noticeable enlargement of the abdomen. This enlargement is due to the physical mass of the fibroids projecting into the abdominal cavity. In some cases, the abdominal distention can be significant enough to be visibly apparent and may be mistaken for other conditions causing abdominal swelling.

Diagnosis and Investigations

Medical History (History Taking): The initial step in diagnosing fibroids involves gathering a detailed account of the patient’s health. This includes inquiring about their specific symptoms, menstrual cycle patterns (duration, heaviness of flow, pain), reproductive history (pregnancies, deliveries, miscarriages), and any other relevant medical conditions or past surgeries. This comprehensive history is crucial for assessing the likelihood of uterine fibroids being the cause of the patient’s issues and helps determine the subsequent diagnostic steps.

General Physical Assessment (Physical Examination): A general physical exam is conducted to evaluate the patient’s overall health status and to look for general signs that might be related to fibroids or their complications. This may involve checking for pallor (unusual paleness of the skin), which can be an indicator of chronic anemia that can develop from prolonged heavy menstrual bleeding often associated with fibroids.

Abdominal Palpation (Abdominal Examination): The abdomen is carefully examined by touch to identify any abnormal swelling or masses in the pelvic-abdominal area. Significantly enlarged fibroids can sometimes be felt through the abdominal wall, especially if they are large and extending beyond the pelvis.

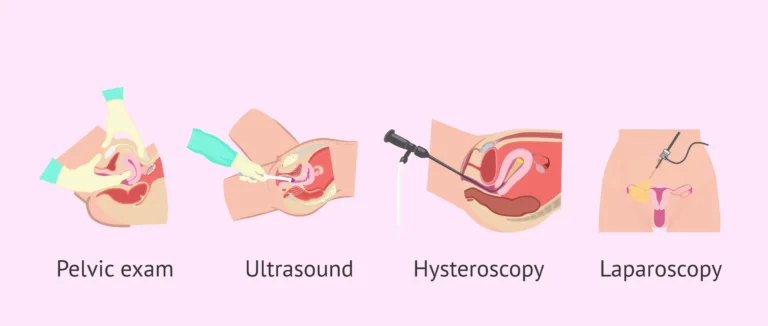

Pelvic Exam (Pelvic Examination): A pelvic examination is a key part of the diagnostic process. During this examination, the healthcare provider manually assesses the uterus to determine its size, shape, and position within the pelvis. Fibroids can cause the uterus to feel enlarged, either uniformly or in an irregular manner (asymmetrically). A speculum examination, where an instrument is used to gently open the vagina, may also be performed to visualize the cervix and upper vagina, allowing for the detection of submucous fibroids that have prolapsed or formed polyps.

Diagnostic Tests (Investigations): To confirm the presence of uterine fibroids and to characterize them further, a range of diagnostic tests may be employed. These can include:

Pregnancy Test: It is essential to rule out pregnancy, as some early pregnancy symptoms can overlap with those of fibroids, and pregnancy itself can cause uterine enlargement.

Complete Blood Count (Full Blood Count – FBC) and Iron Studies: These blood tests are performed to evaluate for anemia. Fibroids, especially submucosal types, are a common cause of heavy menstrual bleeding, which can lead to iron deficiency anemia over time. Iron studies help to assess the body’s iron stores and the severity of any anemia present.

Pelvic Ultrasound (U/S): Pelvic ultrasound is a widely used, non-invasive imaging technique for visualizing the uterus and surrounding pelvic structures. It uses sound waves to create images and is effective in detecting fibroids, determining their size, number, and location within the uterus. It is a relatively accessible and straightforward procedure.

Saline Infusion Sonography (Saline Hysterosonography – SIS): This specialized ultrasound technique enhances the visualization of the uterine cavity. Saline (sterile salt water) is gently introduced into the uterus through a thin catheter while a transvaginal ultrasound is performed. The saline distends the uterine cavity, improving the clarity of the endometrial lining and making it easier to identify submucosal fibroids that protrude into the cavity.

Hysterosalpingography (HSG): HSG is an X-ray procedure primarily used to evaluate the uterine cavity and fallopian tubes, often in the context of infertility investigations. A contrast dye is injected through the cervix into the uterus, and X-rays are taken. While primarily for assessing tubal patency, HSG can also reveal the shape of the uterine cavity and may detect intrauterine fibroids that distort the cavity’s normal outline.

Transvaginal Ultrasound (TVUS): Transvaginal ultrasound involves the insertion of a slender ultrasound probe into the vagina. This approach brings the ultrasound transducer closer to the pelvic organs, providing higher resolution images and a more detailed view of the uterus, ovaries, and surrounding structures. TVUS is particularly useful for obese patients where abdominal ultrasound images might be less clear due to increased tissue depth.

Hysteroscopy: Hysteroscopy is a minimally invasive procedure that allows for direct visual examination of the inside of the uterine cavity. A hysteroscope, a thin, telescope-like instrument with a light source and camera, is inserted through the cervix into the uterus. This provides a direct view of the uterine lining and can precisely identify submucosal fibroids. Hysteroscopy also allows for the possibility of removing submucosal fibroids during the same procedure.

Bimanual Pelvic Examination: While technically part of the physical examination, the bimanual exam deserves emphasis. It involves the healthcare provider using two hands – one on the abdomen and fingers of the other inserted into the vagina – to thoroughly assess the pelvic organs. This technique allows for a detailed evaluation of the uterus’s size, shape, mobility, and consistency, as well as the detection of any abnormal masses or tenderness in the pelvic region.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): MRI is a highly sophisticated imaging modality that uses magnetic fields and radio waves to create detailed cross-sectional images of the body. While not routinely required for diagnosing fibroids, MRI is considered the most accurate imaging technique for comprehensively evaluating fibroids. It provides precise information about the size, location, number of fibroids, and their characteristics (e.g., differentiating fibroids from adenomyosis). MRI may be especially useful in complex cases, when planning surgical intervention, or when more detailed information is needed.

Management of Fibroids

In most cases, fibroids require no intervention unless they are symptomatic. It’s important to note that fibroids commonly decrease in size following menopause, generally ceasing to be a source of concern. The approach to managing fibroids is determined by a number of elements, including:

Patient Age

Whether the patient has had children

Fibroid size and placement within the uterus

Patient’s desire to keep their uterus

Future family planning considerations

For example:

For patients with multiple fibroids who have completed their families, a hysterectomy (removal of the uterus) may be the most suitable treatment. Conversely, for women who have not had children, a myomectomy (surgical removal of fibroids only) might be considered to preserve fertility. Fibroids located in the uterine cavity lining (submucosal) can often be managed through hysteroscopic resection, a minimally invasive surgical technique using a camera inserted into the uterus. Fibroids that are attached to the outer surface of the uterus by a stalk (subserosal pedunculated) can be removed using laparoscopic resection, another minimally invasive surgical approach utilizing small incisions and a camera.

Emergency Treatment:

In emergency situations, a blood transfusion is administered to address significant blood loss and anemia. Emergency surgery is indicated in certain critical scenarios such as when a fibroid becomes infected, in cases of acute torsion (twisting) of a fibroid which cuts off its blood supply, and when fibroids cause intestinal obstruction.

Medical Management:

Pain associated with fibroids can be managed with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) like ibuprofen, which reduce inflammation and pain. For excessive menstrual bleeding (menorrhagia), antifibrinolytic medications such as tranexamic acid may be prescribed to help reduce blood loss. Hormonal birth control, either in pill form or using a hormone-releasing intrauterine device (Mirena), can be effective in controlling heavy menstrual bleeding related to fibroids. To address anemia resulting from heavy bleeding, haematenics such as ferrous sulphate or folic acid are used to improve hemoglobin levels. Intrauterine devices that release levonorgestrel are highly effective at limiting menstrual blood flow and alleviating other fibroid symptoms, generally with minimal side effects. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists, such as Lupron and Synarel, can be used to temporarily lower estrogen and progesterone levels. This hormonal reduction causes fibroids to shrink in size. Mifepristone, a progesterone receptor modulator taken at a dose of 25-50mg twice weekly, can also lead to a reduction in fibroid size and bleeding by blocking the effects of progesterone. Danazol, an androgenic medication, works by suppressing ovulation and can be used in fibroid management.

Surgical Management:

Myomectomy is a surgical procedure focused on removing fibroids while leaving the uterus intact. This is often recommended for women who wish to maintain their fertility. Hysterectomy involves the removal of the entire uterus and is a suitable option for women with numerous fibroids who have completed their childbearing. Endometrial ablation is a procedure to remove the lining of the uterus. Uterine artery embolization is a minimally invasive procedure that reduces blood flow to fibroids. This is achieved by injecting small particles (polyvinyl particles) into the uterine arteries via a catheter inserted in the femoral artery in the groin. Radiofrequency ablation is another minimally invasive technique that uses heat to shrink fibroids. A needle-like device is inserted into the fibroid, and radiofrequency energy is applied to heat and destroy the fibroid tissue.

Indications:

Myomectomy is typically indicated for younger women who desire future pregnancies, those with small or few fibroids, and those experiencing heavy or prolonged menstrual bleeding. Hysterectomy may be recommended in cases of suspected malignancy, when fibroids are large or numerous, when a patient has completed her family and desires definitive treatment, or when a patient is approaching menopause.

Pre and Post Operative Care/Management

This section covers the care provided to patients undergoing gynecological surgeries.

1. Admission and History Taking:

Upon admission, it is important to gather the patient’s personal details, medical background, social history, and gynecological history. A physical examination is then conducted, including measuring vital signs (temperature, respiration rate, blood pressure, and pulse). A thorough head-to-toe assessment is performed to identify any signs of anemia, dehydration, jaundice, or other relevant conditions. A vaginal examination is also conducted to assess for any gynecological abnormalities. A general assessment by the gynecologist is a standard part of the admission process.

2. Informed Consent:

The medical professional must clearly explain the reasons for the planned operation, including its benefits, potential risks, and expected outcomes to the patient. It is important to involve the patient’s partner in this discussion if appropriate and desired by the patient.

3. Investigations:

Several laboratory and diagnostic tests are typically ordered prior to surgery. These include urinalysis, hemoglobin (HB) level measurement, blood grouping and cross-matching to prepare for potential transfusion, abdominal ultrasound scan to visualize the uterus and fibroids, assessment of urea and electrolytes for kidney function, INR/PT (International Normalized Ratio/Prothrombin Time) to assess blood clotting, and ECG/ECHO (electrocardiogram/echocardiogram) if deemed necessary based on the patient’s medical history.

4. Patient Education:

Educating the patient about the surgical procedure, its purpose, potential complications, and possible side effects of anesthesia is crucial. Providing reassurance and counseling is important to alleviate patient anxiety and prepare them emotionally for surgery.

5. Preparing for Surgery:

To prepare for surgery, the patient must abstain from eating and drinking for a specific period before the operation, usually starting from midnight the night before or as instructed by the medical team. An intravenous (IV) line is inserted to administer fluids and medications. Blood is booked in the laboratory to be available if needed during or after surgery. Catheterization, inserting a urinary catheter, is performed to drain the bladder during and immediately after surgery. Pre-medications, which may include medications to relax the patient or reduce nausea, are administered as prescribed by the anesthesiologist.

6. Assisting with Theatre Preparation:

In the operating theatre preparation area, assist the patient to change into a surgical gown. Continue to provide counseling and emotional support to help the patient feel as comfortable and reassured as possible before surgery.

Post-Operative Management:

After the surgery is completed, prepare the post-operative bed in the recovery area or ward to receive the patient. Obtain detailed reports from the surgeon, recovery room nurses, and anesthetists regarding the patient’s condition and the surgery performed. Carefully wheel the patient from the recovery area to the ward. Transfer the patient to a warm and prepared bed. The patient is typically positioned flat (supine) for abdominal surgery or placed in a comfortable position if it was vaginal surgery or as per specific surgical instructions.

Observation:

Close monitoring of the patient’s condition is essential immediately after surgery. Vital signs (temperature, pulse, respiration, blood pressure) are recorded frequently, typically every 15 minutes for the first hour, and then every 30 minutes for the next hour, and then at less frequent intervals as the patient stabilizes until discharge from the recovery area. Observe for any signs of bleeding or swelling (edema) at the surgical site. Regularly check the intravenous (IV) line and blood transfusion line, if applicable, to ensure proper function and flow.

Upon Consciousness:

When the patient begins to regain consciousness after anesthesia, gently welcome them back from the operating theatre. Explain to them that the surgery is completed. Assist with face sponging to refresh the patient. Provide mouthwash for oral hygiene and assist in changing the surgical gown if needed for comfort.

Medical Treatment:

Administer prescribed pain relievers (analgesics) such as Pethidine 100mg, often given every 8 hours for the first 3 doses post-surgery, and then transitioning to a milder pain reliever like Panadol (paracetamol) to continue for up to 5 days as needed. Administer antibiotics, such as ampicillin or gentamicin, as per the doctor’s orders to prevent infection. Offer supportive care with vitamins, including vitamin C, iron, and folic acid, to aid in recovery. Monitor and care for the surgical wound in cases of abdominal surgery. If bleeding from the wound is observed, leave the dressings untouched and inform medical staff. If re-bandaging is required, ensure it is done using sterile technique.

Nursing Care:

Assist the patient with personal hygiene, including bed baths and oral care, especially in the initial post-operative period when mobility may be limited. Encourage the patient to start feeding herself as soon as she is able to tolerate food and fluids. Provide plenty of fluids to maintain hydration. Encourage regular attempts at bowel and bladder emptying, and provide assistance as needed, especially in the early post-operative phase. Initiate chest physiotherapy exercises to prevent respiratory complications and leg exercises to promote blood circulation and avoid blood clots and swelling in the legs and feet. Gradually increase the patient’s activity level and exercise routine as tolerated to prevent stiffness, deformities, and muscle contractures.

Vaginal Surgery Management:

If the patient has undergone vaginal surgery, a vaginal pack may be inserted to control potential hemorrhage. Inspect this pack frequently to monitor for any signs of excessive bleeding. After the vaginal pack is removed, apply vulval padding to absorb any continued bleeding until it stops. Change the vulval pads regularly to maintain hygiene and prevent infection. Swab or clean the vulva area at least every 8 hours to prevent infection and promote healing.

Advice on Discharge:

For patients who have undergone myomectomy and wish to conceive in the future, advise them to avoid conception for approximately 2 years following the surgery and to plan for delivery via Cesarean section due to the uterine scar. For patients who have undergone hysterectomy, inform them clearly that they will no longer be able to conceive or have menstrual periods. Recommend abstaining from sexual intercourse for about 6 weeks to allow for proper healing. Advise against douching during the recovery period. Inform patients that vaginal bleeding or spotting may persist for up to 6 weeks post-surgery, which is considered normal.

Complications of Uterine Fibroids:

Fibroids can lead to several complications, including:

Menorrhagia (heavy menstrual bleeding) leading to anemia

Increased risk of premature birth, labor complications, and miscarriage during pregnancy

Infertility in some cases

Torsion (twisting) of fibroids, causing acute pain

Anemia due to chronic blood loss

Urinary tract symptoms and diseases due to pressure on the bladder and ureters

Postpartum hemorrhage after delivery

Complications during pregnancy and labor that may be associated with fibroids include:

Antepartum hemorrhage (bleeding before birth), which can be caused by placenta previa (placenta covering the cervix) or placental abruption (placenta separating from the uterine wall prematurely)

Spontaneous Abortion (miscarriage)

Fetal growth restriction, where the fetus does not grow at the expected rate

Malpresentation of the fetus (abnormal position in the uterus), such as breech presentation

Increased likelihood of Cesarean section delivery

Labor dystocia (difficult or slow labor)

Premature labor and delivery

Uterine inertia (weak or ineffective uterine contractions) leading to postpartum hemorrhage (excessive bleeding after childbirth)

Obstructed labor, where the fibroid physically blocks the baby’s passage through the birth canal

Subinvolution of the uterus (uterus not returning to its normal size after childbirth) with increased lochia (postpartum vaginal discharge).

We are a supportive platform dedicated to empowering student nurses and midwives through quality educational resources, career guidance, and a vibrant community. Join us to connect, learn, and grow in your healthcare journey

Quick Links

Our Courses

Legal / Policies

Get in Touch

(+256) 790 036 252

(+256) 748 324 644

Info@nursesonlinediscussion.com

Kampala ,Uganda

© 2025 Nurses online discussion. All Rights Reserved | Design & Developed by Opensigma