Conditions of the Lymphatic System

Subtopic:

lymphatic system

Table of Contents

Learning Objectives

Describe the anatomy and components of the lymphatic system, including vessels, nodes, ducts, and lymphoid organs.

Explain the physiological roles of lymph in fluid balance, fat absorption, protein transport, and immune defense.

Identify factors that promote lymph circulation, such as skeletal muscle contractions and arterial pulsations.

Recognize the structure and function of lymph nodes and their role in filtering lymph and initiating immune responses.

Differentiate between key lymphatic tissues and organs including tonsils, spleen, bone marrow, and thymus gland.

Understand the immune processes involved in T-cell maturation within the thymus and the roles of B-cells from bone marrow.

Anatomy and physiology of The Lymphatic System

The lymphatic system is a crucial network intricately linked with the circulatory system. It starts with minute, terminal vessels termed lymphatic capillaries, positioned close to tissues and the interstitial fluid that surrounds them. This system functions as an almost parallel drainage network to the blood circulatory system.

It comprises:

Lymph

Lymph is a clear fluid that acts as a carrier, transporting plasma proteins, bacteria, fats (specifically chylomicrons absorbed from the ileum), and cellular debris from damaged tissues to lymph nodes for processing and removal. This fluid circulates within lymphatic vessels. Its composition is similar to blood plasma and includes lymphocytes and macrophages, which are vital for immune function. Lymph is produced as a filtrate of blood, resulting from pressure within blood capillaries that forces fluid into tissue spaces, becoming interstitial fluid. Approximately 2 liters of lymph are generated daily in an adult, representing about 1–3% of total body weight on average. Lymph is essentially the same in composition as interstitial fluid.

Lymph Vessels/Lymphatics

These are vessel-like structures that serve as pathways for lymph to travel through before re-entering the bloodstream. They extend from lymphatic capillaries, which initiate as closed-ended tubes in interstitial spaces, designed to collect excess fluid. These vessels connect to lymph nodes, tissues, and organs, draining fluid into them for filtration and immune surveillance. Lymph capillaries are structurally similar to blood capillaries, made up of a single layer of endothelial cells. However, they lack a basement membrane, facilitating the entry of larger molecules, such as plasma proteins and waste products, that may have leaked into interstitial spaces. A network of lymphatic vessels is distributed throughout most body tissues, with notable exceptions:

Brain

Spinal cord

Bones

Cornea of the eye

Superficial layer of the skin

Lymph vessels enlarge as they merge, eventually culminating in two primary ducts:

Thoracic Duct

Beginning at the cisterna chyli, a sac-like reservoir located in the lower back region in front of the L1 and L2 vertebrae, this duct drains lymph from the legs, pelvis, abdomen, the left side of the chest and neck, and the left arm. It subsequently delivers this collected lymph into the left subclavian vein at the base of the neck.

Right Lymphatic Duct

Positioned at the base of the neck region, this duct drains lymph from the right side of the chest, the head, the neck, and the right arm, delivering it into the right subclavian vein.

Lymph circulation

The lymphatic system serves as an auxiliary pathway for fluid movement from the interstitial spaces back into the bloodstream. Lymphatic vessels are capable of transporting proteins and larger particulate matter away from tissue spaces. This return of proteins from the interstitial fluid to the blood is crucial for maintaining fluid balance and overall health; its absence would be fatal within approximately 24 hours.

Several factors facilitate lymph flow:

Contraction of surrounding skeletal muscles: Muscle movements exert pressure on lymphatic vessels, propelling lymph forward.

Movement of body parts: Physical activity and changes in body position help to squeeze lymphatic vessels.

Pulsations of adjacent arteries: The rhythmic expansion and contraction of arteries located near lymphatic vessels can assist in lymph movement.

External compression: Pressure applied to the body from external sources can also contribute to lymph flow.

Rhythmic contraction of large lymphatic vessels: Larger lymph vessels possess contractile abilities that help to propel lymph.

The lymphatic “pump” becomes highly active during exercise, significantly increasing the rate of lymph flow. Conversely, lymph flow is slow or nearly non-existent during periods of rest.

Lymph nodes

These are small, oval or bean-shaped organs situated along the course of lymphatic vessels. Typically, multiple afferent lymphatic vessels carry lymph into a single lymph node, while only one efferent vessel carries lymph out. Lymph fluid may pass through approximately eight nodes before re-entering the blood circulation.

Lymph nodes are comprised of lymphatic tissue, which is densely populated with lymphocytes (immune cells) and macrophages (phagocytic cells), as well as reticular tissue. The reticular tissue forms a network of fibers that provide internal structural support within the node.

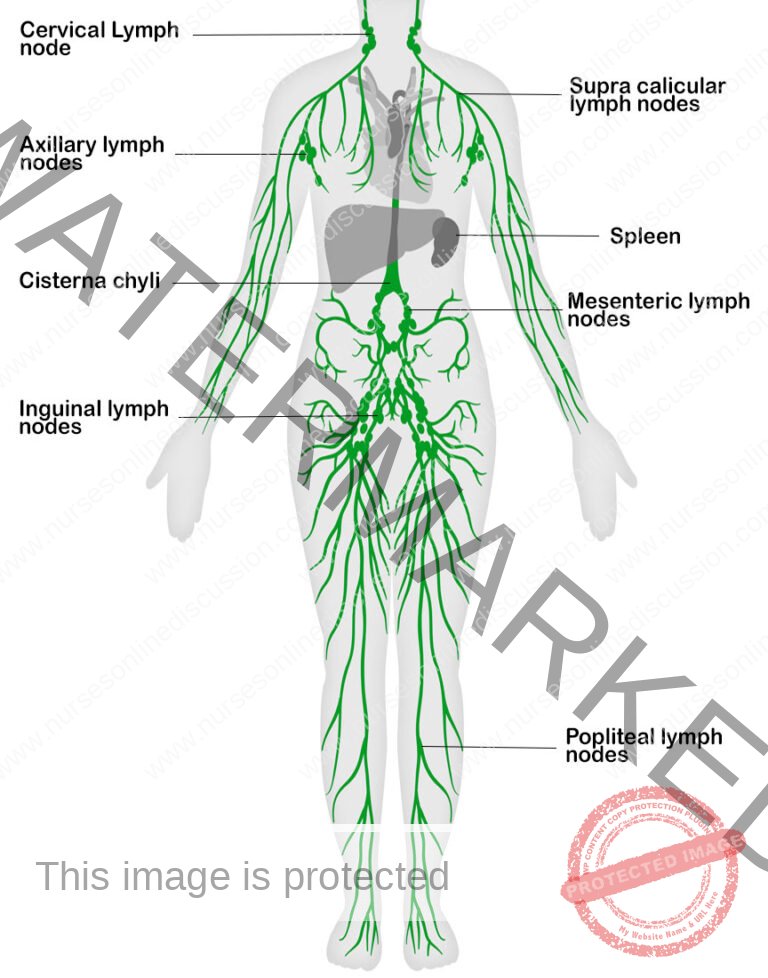

Larger lymph nodes are strategically located throughout the body, arranged in both deep and superficial groups. Examples include:

Cervical Lymph nodes: These nodes drain lymph from the head and neck regions.

Axillary Lymph nodes: Located in the armpit, these nodes drain lymph from the upper limbs.

Hilar nodes, aortic nodes, sternal nodes: These nodes are situated in the chest and drain lymph from the thoracic organs and tissues.

Popliteal nodes and Inguinal nodes: These nodes are located in the back of the knee and groin, respectively, and drain lymph from the lower limbs.

Cisterna chyli: This is a sac-like structure that receives lymph from the abdominal and pelvic cavities.

Lymphoid Tissue

This category includes lymphatic glands, commonly known as lymph nodes, as well as other organized collections of lymphatic cells. Specific examples include:

Pharyngeal tonsils (adenoids): Located near the posterior nasal openings.

Palatine tonsils: Situated at the back of the mouth.

Lingual tonsils: Found at the back and sides of the tongue.

Aggregated lymphoid follicles (Peyer’s patches): Clusters of lymphoid tissue within the small intestine.

Lymphoid tissue is also present in other organs, such as the bone marrow, spleen, liver, lungs, and thymus gland.

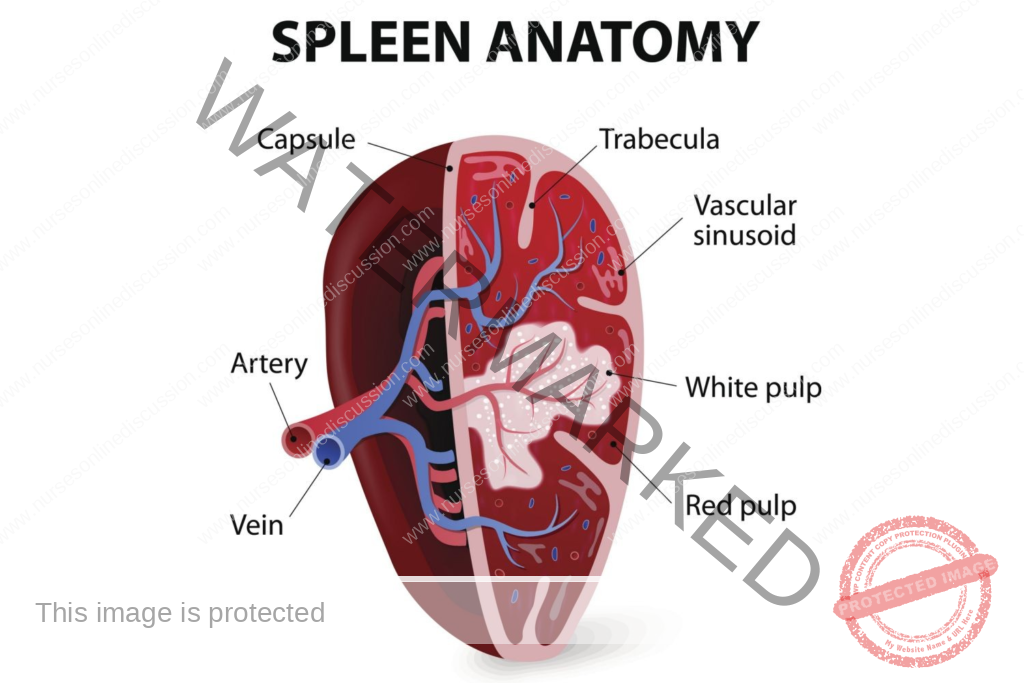

Spleen

This is the largest lymphatic organ in the body, positioned in the left upper quadrant (left hypochondriac region) of the abdominal cavity, between the fundus of the stomach and the diaphragm.

The spleen performs two primary functions:

Destruction of old blood cells: It removes aged or damaged red blood cells from circulation.

Monitoring the body’s immune system: It contains immune cells that identify and respond to pathogens in the blood.

Essentially, the spleen acts as a blood filter.

Bone Marrow

This acts as the primary location for the production of both B-cells and T-cells, crucial components of the immune system. Furthermore, it is responsible for generating monocytes (a type of white blood cell), granulocytes (another type of white blood cell), red blood cells (responsible for oxygen transport), and platelets (essential for blood clotting). B-cells undergo their maturation process within the bone marrow itself. Fundamentally, the bone marrow serves as the origin point for hematopoietic stem cells, the foundational cells from which all blood cell types develop.

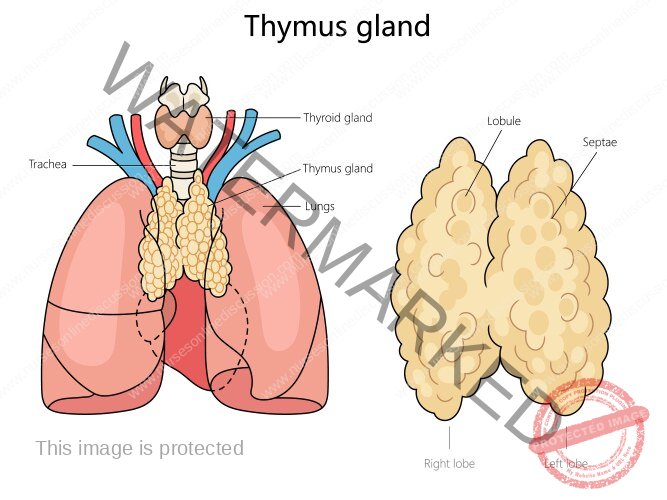

Thymus Gland

This is a grayish organ situated in the chest cavity, specifically between the lungs and just beneath the neck. It is characterized by a bilobed structure, with each lobe containing an outer region known as the cortex and an inner region called the medulla. The medulla is populated with mature lymphocytes, while the cortex is the entry point for pre-T cells. Within the cortex, these developing T-cells undergo a selection process where they are tested for their ability to recognize specific antigens. T-cells that fail this test undergo apoptosis (programmed cell death). The surviving T-cells then migrate to the medulla and subsequently enter the general blood circulation. This gland also secretes a hormone called thymosin, which plays a vital role in the maturation and development of T-lymphocytes.

Function of lymph

Transport of proteins and large particles: Lymph facilitates the movement of substantial molecules, such as proteins, that are too large to directly enter the bloodstream through capillaries.

Transport of fatty acids and cholesterol: Lymph plays a crucial role in the absorption and transportation of fats and cholesterol from the intestines.

Return of excess fluid: Lymph collects surplus fluid from tissues, preventing swelling, and returns it to the circulatory system.

Carry bacteria for destruction: Lymph transports bacteria and other pathogens to the nearest lymph node, where they can be targeted and eliminated by immune cells.

Carry antibodies: Lymph circulates antibodies, proteins that help the body fight off infections.

Transport vitamin K: Lymph assists in the transport of vitamin K, a fat-soluble vitamin, from the intestine into the bloodstream.

Join Our WhatsApp Groups!

Are you a nursing or midwifery student looking for a space to connect, ask questions, share notes, and learn from peers?

Join our WhatsApp discussion groups today!

Join NowRelated Topics

Conditions of the Lymphatic System

- Anatomy and Physiology of the Lymphatic System

- Lymphedema

- Lymphangitis and Lymphadenitis

- Hodgkin’s Disease

Medical Diseases Affecting the Renal System

- Anatomy and Physiology of the Renal System

- Renal Disorders

- Urinary Tract Infections (UTIs)

- Cystitis

- Renal Failure (Acute and Chronic)Nephrotic Syndrome

- Polycystic Kidney Disease (PKD)

- Kidney Stones (Nephrolithiasis)

Medical Conditions Affecting the Endocrine System

- Applied Anatomy and Physiology of the Endocrine System

- Acromegaly/Gigantism (Hyperpituitarism)

- Dwarfism (Panhypopituitarism)

- Addison’s Disease (Adrenal Insufficiency)

- Pheochromocytoma

- Cushing’s Syndrome

- Hyperaldosteronism

- Thyrotoxicosis

- Diabetes Mellitus

Conditions Affecting the Nervous System

- Applied Anatomy and Physiology of the Nervous System

- Trigeminal Neuralgia

- Bell’s Palsy

- Parkinson’s Disease

- Spinal Cord Compression

- Transverse Myelitis

Conditions of the Musculo-Skeletal System

- Anatomy and Physiology of the Musculo-Skeletal System

- Tendonitis

- Rheumatoid Arthritis

- Osteoarthritis

- Gout

- Bursitis

- Ankylosing Spondylitis

- Osteoporosis

- Paget’s Disease

Skin Conditions (Dermatology)

Get in Touch

(+256) 790 036 252

(+256) 748 324 644

Info@nursesonlinediscussion.com

Kampala ,Uganda

© 2025 Nurses online discussion. All Rights Reserved Design & Developed by Opensigma.co