Urinary System

Subtopic:

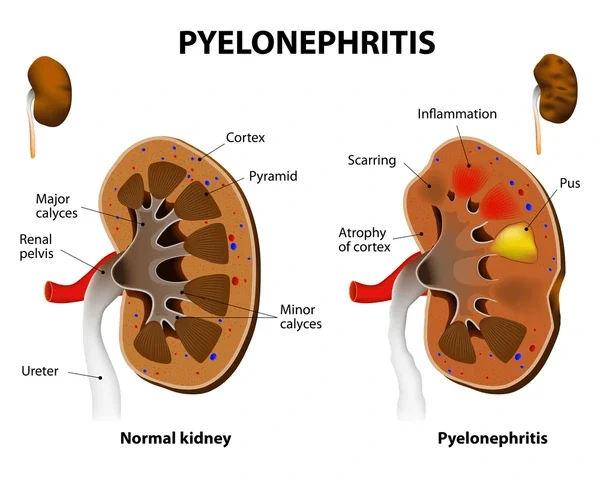

Pyelonephritis

Pyelonephritis is a significant bacterial infection affecting the kidneys, specifically the renal pelvis and parenchyma. It represents a more severe form of urinary tract infection (UTI) compared to lower UTIs like cystitis (bladder infection).

While often a complication of ascending lower UTIs, pyelonephritis can also occur through hematogenous spread (bacteria entering the bloodstream and traveling to the kidneys). Prompt diagnosis and treatment are crucial to prevent potential complications, including kidney damage, sepsis, and chronic kidney disease.

Pyelonephritis is broadly classified into two main types:

Acute Pyelonephritis: This is an active bacterial infection characterized by sudden onset of symptoms such as fever, flank pain, nausea, vomiting, and systemic signs of infection. It is typically caused by bacteria ascending from the lower urinary tract.

Chronic Pyelonephritis: This refers to recurrent or persistent kidney infection that can lead to chronic inflammation, scarring, and progressive kidney damage. It is often associated with underlying structural or functional abnormalities of the urinary tract that predispose individuals to recurrent infections.

Understanding the etiology, pathophysiology, clinical presentation, and management of pyelonephritis is essential for healthcare professionals.

Epidemiology and Risk Factors

Pyelonephritis is a common reason for hospitalization due to infection, particularly in women. While UTIs are more prevalent in women overall, pyelonephritis can affect individuals of all ages and genders.

Epidemiology:

Acute pyelonephritis is significantly more common in women than in men, especially young, sexually active women.

The incidence in men increases with age, often associated with prostatic hypertrophy or other urinary tract obstructions.

Pregnant women are at increased risk due to hormonal changes and mechanical compression of the ureters, which can lead to urinary stasis.

Pyelonephritis is also a concern in infants and young children, where it can be associated with congenital abnormalities of the urinary tract like vesicoureteral reflux (VUR).

Risk Factors:

Several factors increase an individual’s susceptibility to developing pyelonephritis:

Female Gender: Shorter urethra facilitates bacterial ascent.

Sexual Activity: Increases the risk of introducing bacteria into the urethra.

Use of Spermicides and Diaphragms: Can alter vaginal flora and increase bacterial adherence.

Pregnancy: Hormonal changes and mechanical factors contribute to urinary stasis.

History of Previous UTIs: Increases the likelihood of recurrence and potential upper tract involvement.

Urinary Tract Obstruction: Any condition that impedes the normal flow of urine (e.g., kidney stones, enlarged prostate, strictures, tumors) can lead to urinary stasis and increased risk of infection ascending to the kidneys.

Vesicoureteral Reflux (VUR): A condition where urine flows backward from the bladder into the ureters and kidneys, common in children and a significant risk factor for chronic pyelonephritis and kidney scarring.

Neurogenic Bladder: Conditions affecting nerve control of the bladder can lead to incomplete emptying and urinary stasis.

Diabetes Mellitus: Impaired immune function and potential for neurogenic bladder contribute to increased risk.

Immunosuppression: Weakened immune system due to conditions like HIV/AIDS, organ transplantation, or chemotherapy makes individuals more vulnerable to infection.

Indwelling Urinary Catheters: Catheters bypass natural defense mechanisms and provide a direct route for bacteria to enter the bladder and potentially ascend.

Anatomical Abnormalities: Congenital or acquired structural issues in the urinary tract.

Pathophysiology

The most common route of infection in pyelonephritis is the ascending pathway. Bacteria, typically originating from the 大肠 (large intestine) and colonizing the periurethral area, enter the urethra and ascend into the bladder, causing cystitis. From the bladder, these bacteria can then travel up the ureters to the renal pelvis and kidney parenchyma.

Several factors facilitate this ascent:

Bacterial Virulence Factors: Uropathogenic E. coli (UPEC) and other common uropathogens possess fimbriae (pili) and other adhesins that allow them to attach to the epithelial cells lining the urinary tract, resisting the flushing action of urine. They can also produce toxins and enzymes that damage host tissues and evade immune responses.

Impaired Ureteric Peristalsis: Inflammation or obstruction can disrupt the normal wave-like contractions of the ureters that help propel urine downwards, allowing bacteria to ascend more easily.

Vesicoureteral Reflux (VUR): This allows infected urine from the bladder to reflux into the renal pelvis, directly exposing the kidney to bacteria.

Increased Intravesical Pressure: Conditions causing high pressure within the bladder can promote reflux.

Less commonly, pyelonephritis can occur via hematogenous spread. In cases of systemic infection (bacteremia), bacteria circulating in the bloodstream can seed the kidneys, leading to infection. This route is more typical with certain pathogens like Staphylococcus aureus and can occur in individuals with compromised immune systems or intravenous drug users.

Once bacteria reach the kidney, they multiply and trigger an inflammatory response. Neutrophils infiltrate the renal parenchyma, leading to tissue damage, edema, and potential abscess formation. This inflammation disrupts normal kidney function and can lead to the characteristic symptoms of pyelonephritis. In chronic pyelonephritis, repeated or persistent infection and inflammation cause progressive scarring and atrophy of the renal tissue, potentially leading to chronic kidney disease and renal failure.

Causes

The vast majority of acute pyelonephritis cases are caused by bacterial infection.

Bacterial Causes:

Escherichia coli (E. coli): This is the most common causative agent, responsible for 70-95% of uncomplicated pyelonephritis cases. Specific strains of UPEC are particularly adept at causing UTIs due to their virulence factors.

Other Enterobacteriaceae: Klebsiella species, Proteus mirabilis, Enterobacter species, and Serratia species are also common gram-negative culprits, particularly in complicated UTIs or healthcare-associated infections. Proteus mirabilis is noteworthy for its ability to produce urease, an enzyme that breaks down urea into ammonia, increasing urine pH and contributing to the formation of struvite stones, which can cause obstruction and perpetuate infection.

Staphylococcus saprophyticus: A common cause of UTIs in young, sexually active women, though less frequently associated with pyelonephritis compared to E. coli.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa: More often seen in complicated UTIs, particularly in individuals with urinary tract abnormalities or those with indwelling catheters.

Enterococcus species: Can cause UTIs, especially in hospitalized patients or those with underlying urinary tract issues.

Staphylococcus aureus: A less common cause of ascending pyelonephritis but a significant pathogen in hematogenous spread to the kidneys.

Non-Bacterial Causes:

While bacterial infection is the primary cause, inflammation of the renal pelvis and parenchyma can sometimes be associated with non-infectious conditions, though these are less commonly referred to as “pyelonephritis” in the acute infectious sense. Examples include:

Interstitial Nephritis: Inflammation of the kidney tubules and surrounding tissue, which can be caused by drugs, autoimmune diseases, or infections (viral, fungal), but is distinct from bacterial pyelonephritis.

Analgesic Nephropathy: Kidney damage caused by long-term use of certain pain medications.

Radiation Nephritis: Kidney damage resulting from radiation therapy.

However, in the context of clinical pyelonephritis, the focus is overwhelmingly on bacterial etiology.

Clinical Manifestations

The symptoms of acute pyelonephritis are typically more severe and systemic than those of lower UTIs.

Common Symptoms:

Fever: Often high-grade, sometimes with chills and rigors.

Flank Pain: Pain located in the back, just below the ribs, on one or both sides, corresponding to the location of the kidneys. The pain can range from a dull ache to severe tenderness.

Nausea and Vomiting: Common systemic symptoms due to the severity of the infection.

Malaise: A general feeling of being unwell, fatigue, and weakness.

Symptoms of Lower UTI (often preceding or co-occurring): These may include painful urination (dysuria), increased urinary frequency, urgency, and suprapubic pain. However, in some cases, particularly in older adults or those with compromised immune systems, lower UTI symptoms may be absent or subtle.

Less Common or Atypical Symptoms:

Abdominal pain (can sometimes be mistaken for appendicitis or other abdominal issues).

Diarrhea.

Hematuria (blood in the urine), which may be visible or microscopic.

Cloudy or foul-smelling urine.

Symptoms in Specific Populations:

Older Adults: May present with atypical symptoms such as altered mental status, confusion, generalized weakness, or falls, with fever and localized pain being less prominent.

Infants and Young Children: Symptoms can be non-specific, including fever, irritability, poor feeding, vomiting, and failure to thrive.

Chronic pyelonephritis may have subtle or no symptoms initially, or it may present with recurrent episodes of acute pyelonephritis. Over time, as kidney damage progresses, symptoms of chronic kidney disease may develop, such as fatigue, swelling, changes in urination, and high blood pressure.

Diagnosis

Diagnosing pyelonephritis involves a combination of clinical assessment, laboratory tests, and sometimes imaging studies.

Clinical Assessment:

A detailed medical history, including symptoms, their duration, any history of previous UTIs, risk factors, and underlying medical conditions.

Physical examination, including assessment for fever, tenderness in the costovertebral angle (CVA tenderness, elicited by gently tapping the area over the kidneys), and signs of systemic illness.

Laboratory Tests:

Urinalysis: A urine sample is examined for the presence of white blood cells (pyuria), red blood cells (hematuria), bacteria (bacteriuria), and protein. A positive leukocyte esterase and/or nitrite test on a urine dipstick strongly suggests a UTI.

Urine Culture and Sensitivity: This is essential to confirm the presence of bacteria, identify the specific causative organism, and determine its susceptibility to various antibiotics. A clean-catch midstream urine sample is preferred.

Blood Tests:

Complete Blood Count (CBC): May show an elevated white blood cell count (leukocytosis), indicating infection.

Blood Culture: Recommended for patients who are severely ill, have signs of sepsis, or are immunocompromised, to detect bacteria in the bloodstream.

Kidney Function Tests (Serum Creatinine and Urea): Assessed to evaluate kidney function and detect any impairment.

Inflammatory Markers (CRP, ESR): C-reactive protein (CRP) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) may be elevated, indicating inflammation.

Imaging Studies:

Imaging is not always necessary for uncomplicated acute pyelonephritis in otherwise healthy individuals who respond promptly to antibiotic treatment. However, it is indicated in cases of:

Severe illness or lack of response to initial antibiotic therapy (typically within 48-72 hours).

Suspected urinary tract obstruction (e.g., due to stones).

Recurrent pyelonephritis.

Patients with known urinary tract abnormalities.

Complicated pyelonephritis (e.g., in diabetics, immunocompromised individuals, pregnant women, men).

Common imaging modalities include:

Computed Tomography (CT) Scan: The preferred imaging modality for evaluating acute pyelonephritis and detecting complications like renal abscesses, perinephric collections, or obstruction. CT with contrast provides detailed images of the kidneys and urinary tract.

Renal Ultrasound: Useful for detecting urinary tract obstruction (hydronephrosis) and large renal or perinephric abscesses. It is often the initial imaging test in pregnant women to avoid radiation exposure.

Intravenous Pyelogram (IVP): Less commonly used now compared to CT, but can provide information about the structure and function of the urinary tract.

Voiding Cystourethrogram (VCUG): Primarily used in children with pyelonephritis to evaluate for vesicoureteral reflux.

Medical Management

The primary goal of managing acute pyelonephritis is to eradicate the bacterial infection, alleviate symptoms, and prevent complications. Treatment typically involves antibiotic therapy.

Antibiotic Therapy:

Empirical Therapy: Initial antibiotic treatment is usually started empirically based on the likely causative organisms and local resistance patterns, before urine culture results are available.

Definitive Therapy: Once culture and sensitivity results are available, the antibiotic regimen should be adjusted to target the specific pathogen and its susceptibility profile.

Route of Administration: Severely ill patients, those with nausea and vomiting preventing oral intake, or those requiring hospitalization are typically started on intravenous (IV) antibiotics. Patients who are less severely ill and can tolerate oral intake may be treated with oral antibiotics.

Duration of Therapy: The duration of antibiotic treatment for acute pyelonephritis is typically 7 to 14 days, depending on the severity of the infection, the patient’s response to treatment, and the specific antibiotic used.

Commonly Used Antibiotics:

Fluoroquinolones (e.g., Ciprofloxacin, Levofloxacin): Often used for empirical treatment, especially in areas with high E. coli resistance to other agents.

Extended-spectrum Cephalosporins (e.g., Ceftriaxone, Cefepime): Effective against a broad range of gram-negative bacteria and often used for initial IV therapy.

Aminoglycosides (e.g., Gentamicin, Tobramycin): Potent against gram-negative bacteria, often used in combination with other antibiotics for severe infections.

Piperacillin-Tazobactam or Carbapenems (e.g., Imipenem, Meropenem): Reserved for severe, complicated infections or those caused by multidrug-resistant organisms.

Trimethoprim-Sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX): Can be used if the organism is susceptible, but resistance is common in some areas.

Oral options for step-down therapy: Once the patient improves clinically, IV antibiotics can often be switched to oral agents to complete the course.

Hospitalization Criteria:

Hospitalization is often required for patients with acute pyelonephritis who meet certain criteria:

Severe illness or signs of sepsis (e.g., hypotension, tachycardia, altered mental status).

Inability to tolerate oral fluids or medications due to nausea and vomiting.

Underlying conditions that complicate management (e.g., diabetes, immunosuppression, chronic kidney disease).

Suspected urinary tract obstruction.

Pregnancy.

Lack of response to outpatient oral antibiotic therapy.

Diagnostic uncertainty.

Supportive Care:

In addition to antibiotics, supportive measures are important:

Hydration: Ensuring adequate fluid intake, often intravenously initially, to maintain hydration and promote urine flow.

Pain Management: Administering analgesics to relieve flank pain and discomfort.

Antiemetics: Medications to control nausea and vomiting.

Monitoring: Close monitoring of vital signs, urine output, kidney function, and response to treatment.

Management of chronic pyelonephritis involves identifying and correcting any underlying urinary tract abnormalities, long-term low-dose antibiotic prophylaxis to prevent recurrent infections, and managing complications like hypertension and chronic kidney disease.

Complications

Pyelonephritis, if not promptly and effectively treated, can lead to several complications:

Renal Abscess: A localized collection of pus within the kidney tissue.

Perinephric Abscess: A collection of pus in the tissue surrounding the kidney.

Emphysematous Pyelonephritis: A severe, life-threatening infection characterized by gas formation within the kidney parenchyma and surrounding tissues, most often seen in diabetic patients.

Papillary Necrosis: Damage and sloughing of the renal papillae, which can lead to obstruction and kidney damage.

Sepsis and Septic Shock: Bacteria from the kidney can enter the bloodstream, leading to a systemic inflammatory response that can be life-threatening.

Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD): Recurrent or chronic pyelonephritis, particularly in the presence of underlying abnormalities like VUR, can cause progressive kidney scarring and loss of function, leading to CKD and potentially end-stage renal disease.

Hypertension: Kidney damage can contribute to the development or worsening of high blood pressure.

Prevention

Preventing pyelonephritis largely focuses on preventing lower UTIs and addressing underlying risk factors. Strategies include:

Maintaining Good Hydration: Drinking plenty of fluids helps flush bacteria from the urinary tract.

Proper Hygiene: Wiping from front to back after using the toilet (for women) helps prevent the spread of bacteria from the 大肠.

Urination After Intercourse: Urinating shortly after sexual activity can help expel bacteria introduced into the urethra.

Avoiding Irritating Products: Limiting the use of feminine hygiene sprays, douches, and harsh soaps in the genital area.

Prompt Treatment of Lower UTIs: Seeking medical attention and completing the full course of antibiotics for symptoms of cystitis to prevent the infection from ascending to the kidneys.

Managing Underlying Conditions: Controlling diabetes, addressing urinary tract obstructions, and managing neurogenic bladder can reduce the risk of pyelonephritis.

Identification and Management of VUR: Screening and treatment for VUR in children with recurrent UTIs are important to prevent kidney scarring.

Appropriate Catheter Care: Strict sterile technique during insertion and proper maintenance of indwelling urinary catheters are crucial to minimize infection risk.

Prognosis

The prognosis for acute pyelonephritis is generally good with prompt and appropriate antibiotic treatment. Most individuals recover fully without long-term kidney damage. However, delays in treatment, severe infection, underlying risk factors (such as obstruction or VUR), and the development of complications can negatively impact the prognosis.

Chronic pyelonephritis carries a less favorable prognosis due to the potential for progressive kidney scarring and loss of function, which can lead to chronic kidney disease and its associated complications. Early identification and management of underlying causes are crucial to slow the progression of kidney damage in chronic cases.

We are a supportive platform dedicated to empowering student nurses and midwives through quality educational resources, career guidance, and a vibrant community. Join us to connect, learn, and grow in your healthcare journey

Quick Links

Our Courses

Legal / Policies

Get in Touch

(+256) 790 036 252

(+256) 748 324 644

Info@nursesonlinediscussion.com

Kampala ,Uganda

© 2025 Nurses online discussion. All Rights Reserved | Design & Developed by Opensigma